Chapter 21 Cleaning, disinfection and sterilization

Introduction

All staff involved with anaesthetic equipment have a duty of care to ensure that the risk of hospital-acquired infection from anaesthetic equipment is kept to an absolute minimum. To this end in the UK, guidelines on infection control in anaesthesia were first published by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) in 2002 and updated in 2008.1 Also in the UK, healthcare organizations now have a legal responsibility to implement changes to reduce healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs). The Health Act 20062 provided the Healthcare Commission with statutory powers to enforce compliance with the Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare Associated Infection.

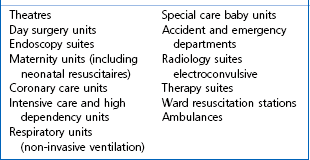

Although there are only a limited number of published reports relating to cross-infection,3,4 the AAGBI recommendation was that all reusable anaesthetic equipment must be appropriately decontaminated prior to patient use and single-use items must be discarded immediately following use. Unfortunately, wide variation in decontamination practices between anaesthetic departments is well recognized. This can be avoided by ensuring that every hospital has a comprehensive infection control policy in place for all anaesthetic equipment, with a nominated anaesthetist and infection control doctor (ICD) taking lead responsibilities.5 Such a policy should be evidenced-based and subject to periodic audit and review. Other useful UK web-based resources include the National Resource for Infection Control and the NHS Library (Surgery, Theatres and Anaesthesia Specialist Library). Key areas requiring risk assessment are listed in Table 21.1.

The aim of this chapter is not to be prescriptive, but to provide the necessary background information for a hospital to formulate its own anaesthetic equipment infection control policy in order to minimize the risk of HCAIs and comply with the UK’s ‘Health Act 2006’.2

Risk assessment and the decontamination process

Contaminated medical devices are typically classified into three infection risk categories:6

1. High risk (critical) devices – items in contact with a break in the skin, mucous membranes or introduced into a sterile body area. Such items must be sterile at the time of use. Examples include surgical instruments, dressings, catheters and prosthetic devices.

2. Intermediate risk (semi-critical) devices – defined as devices in contact with intact mucous membranes or contaminated with readily transmissible organisms (which do not penetrate skin or enter sterile parts of the body – see high risk devices). Disinfection is required though sterilization is preferred if the devices are heat-stable. Examples include endoscopes and respiratory equipment.

3. Low risk (non-critical) devices – items in contact with healthy intact skin. Cleaning, typically using hot water and a neutral detergent or a disposable detergent wipe, and drying are adequate for such items. Examples include non-disposable ECG electrodes, sphygmomanometer cuffs and stethoscopes.

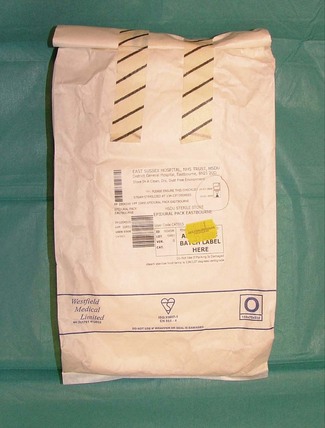

If disposable anaesthetic equipment is chosen (Fig. 21.1), then a risk assessment may not be required. However, it is important to remember that disposable equipment will be for ‘single use’ or ‘single patient use’ only. ‘Single use’ indicates that the manufacturer intends the item to be used once only on an individual patient and then discarded. The packaging will be labelled either ‘Single use’, ‘Do not re-use’ or with the symbol  .

.

’Single patient use’ indicates that the manufacturer advises that the item may be used more than once on the same patient.7 Examples of ‘single patient use’ items in anaesthesia include ventilator tubing and bacterial/viral filters used in critical care units.

Terminology

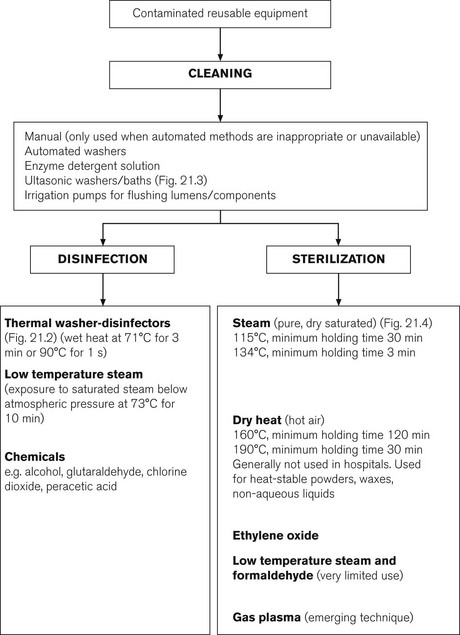

Cleaning

This is the physical removal of infectious agents or organic matter. It involves washing with a solvent (usually water and detergent), which may be heated (e.g. thermal washer disinfection, Fig. 21.2). This process does not necessarily destroy infectious agents. It is an essential process prior to disinfection or sterilization to remove bioburden. Items may also be placed in a water bath incorporating an ultrasound generator (Fig. 21.3). The ultrasound causes the water to vibrate at high frequencies so that it literally ‘shakes’ off organic matter. Ultrasonic washers are particularly useful for equipment where conventional cleaning methods might not reach some aspects of the device, or where items are too delicate to be physically scrubbed (e.g. some ophthalmic instruments).

Sterilant

This is a liquid chemical agent, which can kill bacteria, fungi, viruses and bacterial spores (e.g. gluteraldehyde, chlorine dioxide, peracetic acid). However, this term is not precise and is not generally used. The term high-level disinfectant is preferred. A flow chart of appropriate decontamination methods is shown in Fig. 21.4.

Infection control strategies

Factors to be considered

Single-use versus reusable anaesthetic equipment

Infection control measures have been greatly simplified with the introduction of single-use anaesthetic equipment. Decontamination issues, already outlined with reusable equipment, will not be relevant. However, when preparing an option appraisal, the revenue, procurement and waste disposal costs of single-use equipment needs to be balanced against capital procurement costs for new equipment and SSD charges for reprocessing items. In addition, careful thought needs to be given to where disposable equipment will be stored. To avoid compromising environmental cleaning standards, good communication is required between theatre and supply managers. An example of a local infection control policy for anaesthetic equipment is shown in Table 21.2.

Table 21.2 An example of a local infection control policy for anaesthetic equipment

| EQUIPMENT | ACTION | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Airways | ||

| Oral/nasopharyngeal | Single-use | |

| Plastic endotracheal | Single-use | |

| Tracheostomy tubes | Single-use | |

| Angle pieces | Single-use | |

| Catheter mounts | Single-use | |

| Red rubber endotracheal | Return to SSD | |

| Reusable laryngeal masks | Return to SSD | 40 uses maximum* |

| Single-use laryngeal masks (and other supraglottic airway devices) | Single-use | |

| Anaesthetic breathing systems (theatres) | Disposable | AAGBI recommends that anaesthetic circuits are changed on a weekly basis. A bacterial/viral filter should be used with every patient. Change between patients if visibly contaminated or used for highly infectious cases, e.g. tuberculosis.4 External surfaces routinely cleaned with detergent wipes between cases.13 |

| Circle absorbers | As for ventilators (see below) | Single-use bacterial/viral filter for each patient |

| Anaesthetic masks | Single-use | |

| Bougies | ||

| Gum elastic | Return to SSD | Five uses maximum* |

| Others | Single-use | |

| Entonox delivery system (including mouthpiece/mask, tubing, one-way expiratory demand valve) | Single-use | |

| Laryngoscope blades and handles | Return to SSD or single use | |

| Manual resuscitators (self-inflating bags used at resuscitation) | Single-use | |

| Oxygen mask and tubing | Single-use | |

| Paediatric resuscitaire, facemask and tubing | Single-use | |

| Temperature probes | Single-use | |

| Ventilators (anaesthetic machine) | Routine disinfection not required except for external surfaces. Follow cleaning and maintenance policies for specific ventilators | In ICU, bacterial/viral filter placed on ventilator expiratory port and changed daily* or sooner since single-patient use only |

| Ventilator tubing (ICU) | Disposable | Change circuits weekly or sooner since single patient use only (see above) |

| Flexible fibre-optic laryngoscopes and bronchoscopes | Reusable following national guidelines8 | Only reprocessed in a specialist endoscopy unit |

*Manufacturers’ recommendation; SSD, Sterile Services Department; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; AAGBI, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. (After King and Cooke 20013 with permission from The Hospital Infection Society.)

Disinfection or sterilization

Decontamination by heat rather than by chemicals is always preferred. Disinfection by washer-disinfectors (Fig. 21.2) or low temperature steam is commonly employed, since autoclaving (with dry saturated steam) may damage anaesthetic equipment that is repeatedly processed.5 Equipment used for invasive procedures or that comes into contact with broken skin or mucous membranes always requires sterilization.

Centralization of decontamination services

When preparing an infection control action plan, it should be agreed at the outset with all relevant parties, that reprocessing of contaminated anaesthetic equipment should, whenever possible, be undertaken outside the clinical environment in central decontamination units or SSDs (Fig. 21.5).1,6 Stand-alone autoclaves in theatres are not acceptable. Their use necessitates instrument cleaning (the most important component of the decontamination process) within the theatre complex. Furthermore, the scrupulous quality control measures required for the safe use of autoclaves cannot be guaranteed outside non-specialist areas.

Heat-labile instruments

Items of equipment needing high-level disinfection, but unable to tolerate high temperatures, such as endoscopes, pose particular infection control problems. Their decontamination should be undertaken in designated endoscopy units with appropriately trained personnel.7 The use of chemical disinfectants, because of their toxicity, needs to be strictly controlled and subject to risk assessments in accordance with the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations, COSHH.9

Endoscope processing

Automated decontamination

Endoscopes first need manual cleaning before being attached into the machines. They are then processed at around 37°C through a cycle that starts with a leak test and continues through washing with enzymatic detergents, chemical disinfection and rinsing. Leak testing is necessary to ensure integrity of the internal lining and external wrapping of the fibrescope which would otherwise allow ingress of the caustic fluids and also pose an infection risk. The working channel(s) of the endoscope is connected into the washers so that it receives the same processing as the outside. Typical cycle times are of the order of 30 min (Fig. 21.6).

Drying cabinets

Concern in the UK, about contamination from airborne pathogens and the potential for growth of micro-organisms in stagnant fluid in endoscope channels, has resulted in recommendations requiring that endoscopes are processed within at most 3 h prior to use unless they have been stored under particular conditions. In practice this obligates the use of a dedicated automated drying cabinet, allowing storage times of 3 days to a week (Fig. 21.7).

Standard precautions

The consistent application of effective hand hygiene is the cornerstone of good infection control practice and will minimize the risk of bacterial contamination of the operating theatre environment by anaesthetists (e.g. computer keyboard and telephones10,11).

Tracking of reusable anaesthetic equipment

SSDs must have tracking systems in place (Fig. 21.8) to enable reusable instruments to be traced to an individual patient in the event of a ‘clinical incident’; for example, failure of the decontamination process or instruments being used on a patient with previously unsuspected Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD).12 Furthermore, some reuseable anaesthetic equipment (e.g. laryngeal masks, gum elastic bougies) can only be reprocessed a finite number of times according to the manufacturers’ instructions. A suitable tracking system therefore needs to be agreed between SSD and theatre staff, so that specific items of equipment are discarded after the maximum permitted number of uses. Single-use equipment overcomes the need for tracking systems to be in place.

Damage caused by the decontamination process

Some anaesthetic equipment, made from rubber or plastics, may be destroyed by autoclaving at 115–134°C. Use of washer-disinfectors operating at lower temperatures may then be the preferred option. Manufacturers will provide written instructions on the decontamination of reusable equipment and it is important that these are followed to avoid instrument damage. Some light sources for metal laryngoscope blades lose luminance with repeated high-temperature autoclaving.14 This may influence the decision to procure single-use items.

Bacterial/viral filters and anaesthetic breathing systems

Bacterial/viral filters can be used to protect anaesthetic breathing systems from contamination. Although their role in the prevention of nosocomial pneumonia is controversial,15 the AAGBI do recommend that a new bacterial/viral filter be used for every patient.1 Similarly, implementation of a local policy on the reuse of breathing systems in line with manufacturers’ instructions is recommended. Some breathing systems are marketed with instructions which permit reuse for a period of up to 1 week, if a new bacterial/viral filter is used with every patient. However, to ensure consistent application of infection control policies the AAGBI now recommends that anaesthetic circuits are routinely changed on a daily basis (see Table 21.2).

Prion disease

Abnormally shaped prion proteins are implicated as the causative agents in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, of which variant (v) and sporadic CJD are examples. Both result in progressive neurological symptoms and death. Data from the CJD surveillance unit in Edinburgh indicates that deaths in the UK due to definite and possible cases of CJD amounted to 1476 from 1990 to March 2010.16 Of these, only 168 are considered to be due to vCJD whilst sporadic CJD accounts for 1129 cases. Iatrogenic CJD (due to accidental transmission during medical or surgical procedures) has numbered between 0 and 6 cases per year and is mostly secondary to blood products and soft-tissue allografts. There have been no known transmissions of vCJD via surgery or use of tissues or solid organs.17

The prion protein is remarkably resistant to conventional methods of disinfection and sterilization.17 Standard washing techniques do reduce the concentration of prions in an exponential fashion, but 10–20 cycles are required to produce negligible levels. Standard decontamination methods will not protect against transmission of prion proteins, although the risk of transmission by surgical equipment from patients with undiagnosed CJD is thought to be minimal. Specific decontamination processes, which are the specialist realm of SSDs, have been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens and the Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy Working Group and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.12,17

From the anaesthetic perspective, the transmission of prion disease can be reduced by the strict adherence to standard universal infection control precautions and the employment of single-use instruments when they are considered to be as reliable and safe as reuseable alternatives. To avoid contamination by tonsillar and adenoid tissue in adenotonsillectomy, laryngeal masks, bougies and other intubation aids should not be reused. However, the AAGBI does not recommend the mandatory use of disposable laryngoscopes if laryngoscopy could be difficult, in view of the extremely low risk of transmission.1

Equipment used on definite, probable, possible or ‘at risk’ CJD patients should be dealt with as follows:17

1. If used on patients with definite or probable CJD, the instruments should not be reused and must be destroyed by incineration or quarantined exclusively for reuse on the same patient.

2. If used on patients with possible CJD, reusable equipment should be quarantined until the diagnosis is either confirmed (when equipment must be destroyed) or excluded (following which equipment may re-enter general use). Suspect patients are defined as having clinical symptoms suggestive of CJD, but have not yet had the diagnosis confirmed.

3. For ‘at risk’ patients, single-use equipment should be used wherever possible. Asymptomatic patients, who are potentially at risk of developing CJD or a related disorder include recipients of hormones derived from human pituitary glands, recipients of human dura mater grafts and those with family history of CJD. For procedures involving high- or medium-risk tissues (i.e. brain, spinal cord, anterior and posterior parts of the eye, lymphoid tissue, olfactory epithelium), instruments should be disposed of by incineration. However, for procedures on low-risk tissues, normal reprocessing guidance should be followed.

1 Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Infection control in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1027–1036.

2 Department of Health. The Health Act 2006: Code of practice for the prevention and control of healthcare associated infections. Revised 2008. London: DoH Publications; 2008.

3 Neal TJ, Hughes CR, Rothburn MM, Shaw NJ. The neonatal laryngoscope as a potential source of cross-infection. J Hosp Infect. 1995;30:315–317.

4 Mehtar S, Drubu YJ, Vijeratnam S, Meyet F. Cross-infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae through a resuscitaire. Br Med J. 1986;295:25–26.

5 King TA, Cooke RPD. Developing an infection control policy for anaesthetic equipment. J Hosp Infect. 2001;47:257–261.

6 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Sterilisation, disinfection and cleaning of medical equipment: guidance on decontamination from the Medical Advisory Committee to Department of Health. Parts 1, 2 and 3. London: DoH; 2010.

7 Medical Devices Agency. Single-use medical devices: implications and consequences of reuse. MDA DB 2000(04). London: Medical Devices Agency; 2000.

8 Medical Devices Agency. Decontamination of endoscopes. MDA DB 2002 (05). London: Medical Devices Agency; 2002.

9 Health and Safety Executive. Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002 (as amended, fifth edition): Approved Code of Practice and guidance. London: HSE Books; 2005.

10 Jeske HC, Tiefenthaler W, Hohlrieder M, Hinterberger G, Benzer A. Bacterial contamination of anaesthetists’ hands by personal mobile phone and fixed phone use in the operating theatre. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:904–906.

11 Fukada T, Iwakiri H, Ozaki M. Anaesthetists’ role in computer keyboard contamination in an operating room. Journal of Hospital. Infection. 2008;70:148–153.

12 NHS Estates. A guide to the decontamination of reusable surgical instruments. Leeds: NHS Estates; 2003.

13 Baillie JK, Sultan P, Graveling E, Forrest C, Lafong C. Contamination of anaesthetic machines with pathogenic organisms. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:1257–1261.

14 Bucx MJL, Veldman DJ, Beenhakker MM, Koster R. The effect of steam sterilisation at 134°C on light intensity provided by fibrelight Macintosh laryngoscopes. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:875–878.

15 Lorente L, Lecuona M, Málaga J, Revert C, Mora ML, Sierra A. Bacterial filters in respiratory circuits: an unnecessary cost? Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2126–2130.

16 National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit, www.cjd.ed.ac.uk/figures.

17 Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens and the Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy Working Group. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agents: safe working and the prevention of infection: part 4. London: DoH; 2010.