CHAPTER 49 Classification of urogynaecological disorders

Introduction

It is increasingly recognized that colorectal surgeons have an important role in the management of pelvic floor disorders. The studies of Snooks et al (1984a,b) and Sultan et al (1993) show the traumatic effects of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor and anal sphincters. Wall and de Lancey (1991) succinctly summarized the need for a holistic approach involving gynaecologists, urologists and colorectal surgeons in the management of pelvic floor disorders.

Terminology

Nine reports have now been published, as follows.

Nowadays, the term ‘stress incontinence’ is retained for the symptom of involuntary loss of urine on physical exertion and the sign of urine loss from the urethra immediately on increase in abdominal pressure. The term ‘genuine stress incontinence’ was proposed by the International Continence Society in 1976 (Bates et al 1976) to mean the condition of involuntary loss of urine when ‘the intravesical pressure exceeds the maximum urethral pressure in the absence of a detrusor contraction’. This condition has a number of synonyms: urethral sphincter incompetence, stress urinary incontinence and anatomical stress incontinence. The authors prefer the term ‘urethral sphincter incompetence’ because this accurately describes the pathophysiology of this condition.

In a similar way, the term ‘dyssynergic detrusor dysfunction’ was introduced by Hodgkinson et al in 1963 and other synonyms followed: urge incontinence, uninhibited bladder, bladder instability/unstable bladder and, more recently, overactive bladder. In 1979, the International Continence Society defined an unstable bladder as one ‘shown objectively to contract, spontaneously or on provocation during the filling phase, while the patient is attempting to inhibit micturition. Unstable contractions may be asymptomatic and do not necessarily imply a neurological disorder.’ The contractions are phasic. Another term, ‘low compliance’, is used to mean a gradual increase in detrusor pressure without a subsequent decrease during bladder filling. The term ‘neurogenic detruser overactivity’ is used for phasic uninhibited contractions when there is objective evidence of a relevant neurological disorder. Terms to be avoided include ‘hypertonic’, ‘spastic’ and ‘automatic’.

Classification

Incontinence

The social isolation caused by incontinence is demonstrated by 25% of patients delaying for more than 5 years before seeking advice, owing to embarrassment (Norton et al 1988). Ostracism and rejection by relatives may lead to an elderly patient being institutionalized solely because of incontinence; paradoxically, some allegedly ‘caring’ institutions will not accept an elderly patient if she is incontinent.

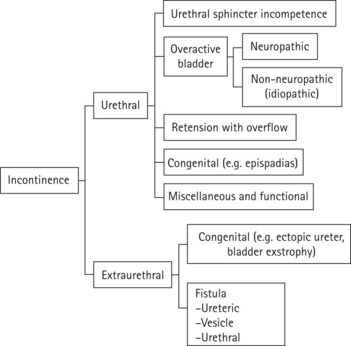

Incontinence may be divided into urethral and extraurethral conditions (Figure 49.1).

Urethral conditions

Urethral sphincter incompetence (urodynamic stress incontinence)

This is the most common urethral condition, has several causes and can present from childhood (see Chapter 52). The original classification of type 1, 2 and 3 is facile. It is realistic to acknowledge that whilst only some patients have ‘urethral hypermobility’, all will have some degree of sphincter incompetence, otherwise they would not leak. Type 3 is gross incontinence with a maximum urethral closure pressure below 20 cmH2O (more usefully termed ‘intrinsic sphincter defect’). Conventional bladder neck elevating surgery or even midurethral support surgery is unlikely to succeed in type 3 patients; what is required is something to restore urethral pressure, such as an artificial urinary sphincter. For the vast majority (i.e. old type 1 and 2), either a bladder neck elevating procedure, such as a colposuspension or sling, or a midurethral support procedure, such as a tension-free vaginal tape procedure, will likely suffice. The latter has shown that lack of midurethral support is a significant cause of sphincter incompetence.

Extraurethral conditions

These may be divided into congenital and acquired. Extraurethral conditions may be distinguished from urethral conditions by the symptom of continuous incontinence. The congenital disorders include ectopic ureter and bladder exstrophy. Acquired conditions include urinary fistulae, which in the Western world are largely iatrogenic, the majority occurring after abdominal hysterectomy for benign conditions (see Chapter 57). Other causes include pelvic carcinoma and its attendant surgery or radiotherapy. In the developing world, obstetrical causes such as obstructed labour with an impacted vertex are more common. If the fistula is small, skill and patience are required to detect it.

Genital prolapse

Prolapse should not be considered in isolation as it is sometimes associated with urethral sphincter incompetence, or with perineal descent and faecal incontinence (see Chapter 55). The latter conditions represent an important interface with the colorectal surgeon.

Urgency and frequency

These symptoms can, of course, be part of a urinary disease process, such as urinary tract infection or overactive bladder, but can often present as single or combined symptoms in the absence of an obvious pathology (see Chapter 56).

Conclusion

Abrams P, Blaivas J, Stanton SL, Andersen J. Standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function. International Continence Society. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 1988;114(Suppl):5-19.

Anderson JT, Blaivas JG, Cardozo L, Thüroff J. Lower urinary tract rehabilitation techniques: seventh report on the standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. International Urogynecology Journal. 1992;3:75-80.

Bates P, Bradley W, Glen E, et al. First report on standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function. International Continence Society. British Journal of Urology. 1976;48:39-42.

Bump R, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. Standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. ICS Committee on Standardization of Terminology. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:10-17.

Fonda D, Resnick NM, Colling J, Burgio K, et al. Outcome measures for research of lower urinary tract dysfunction in frail older people. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1998;17:173-281.

Griffiths D, Hofner K, van Mastrigt R, et al. Standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: pressure flow studies of voiding, urethral resistance and urethral obstruction. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1997;16:1-18.

Hodgkinson CP, Ayers M, Drukker B. Dyssynergic detrusor dysfunction in the apparently normal female. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1963;87:717-730.

Lose G, Fantl JA, Victor A, et al. Outcome measures for research in adult women with symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1998;17:255-262.

Mattiasson A, Djurhuus JC, Fonda D, et al. Standardization of outcome studies in patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction: a report on general principles from the Standardisation Committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1998;17:249-253.

Norton P, MacDonald L, Sedgwick P, Stanton SL. Distress and delay associated with urinary incontinence, frequency and urgency in women. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1988;297:1187-1189.

Snooks S, Barnes P, Swash M. Damage to innervation of the voluntary anal and periurethral sphincter musculature in incontinence: an electrophysiological study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1984;47:1269-1273.

Snooks S, Swash M, Henry M, Setchell M. Injury to innervation of pelvic floor sphincter musculature in childbirth. The Lancet. 1984;ii:546-550.

Stöhrer M, Goepel M, Kondo A, et al. The standardisation of terminology in neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1999;18:139-158.

Sultan A, Kamm M, Hudson C, Thomas J, Bartram C. Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1905-1911.

Thuroff J, Mattiasson A, Anderson JT, et al. Standardization of terminology and assessment of functional characteristics of intestinal urinary reservoirs. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1996;15:499-511.

Wall LL, de Lancey J. The politics of prolapse: a revisionist approach to disorders of the pelvic floor in women. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 1991;34:486-496.

Cardozo L, Staskind D. Textbook of Female Urology and Urogynaecology. London: Martin Dunitz; 2001.

Lentz G. Urogynecology. London: Arnold; 2000.

Mundy A, Stephenson T, Wein A. Urodynamics: Principles, Practice and Application, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.

Ostergard D, Bent A. Urogynecology and Urodynamics: Theory and Practice, 4th edn. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

Sand P, Ostergard D. Urodynamics and Evaluation of Female Incontinence. London: Springer-Verlag; 1995.

Stanton SL, Tanagho E. Surgery of Female Incontinence, 2nd edn. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1986.

Stanton SL, Monga A. Clinical Urogynaecology, 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Stanton SL, Owyer PL. Urinary Tract Infection in the Female. London: Martin Dunitz; 2000.

Stanton SL, Zimmern P. Female Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery. London: Springer-Verlag; 2002.

Wall L, Norton P, de Lancey J. Practical Urogynaecology. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1993.

Walters M, Karram M. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Surgery, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1999.

Zacharin RF. Obstetric Fistula. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1988.