Classification and Pathophysiologic Aspects of Respiratory Failure

This chapter presents an overview of the problem of respiratory failure and discusses the different pathophysiologic types and consequences of respiratory insufficiency. Chapter 28 addresses a specific form of acute respiratory failure known as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which does not require the presence of preexisting lung disease. Chapter 29 considers some principles of management of respiratory failure, as well as specific modalities of current therapy.

Classification of Acute Respiratory Failure

In practice, it is most convenient to classify acute respiratory failure into two major categories on the basis of the pattern of gas exchange abnormalities. In the first category, hypoxemia is the major problem. The patient’s PCO2 is normal or even low. This condition is the hypoxemic variety of acute respiratory failure. For example, localized diseases of the pulmonary parenchyma (e.g., pneumonia) can result in this type of respiratory failure if the disease is sufficiently severe. However, an even broader group of etiologic factors causes hypoxemic respiratory failure by means of a generalized increase in fluid within the alveolar spaces, often as a result of leakage of fluid from pulmonary capillaries. The latter problem is frequently called ARDS and can be the consequence of a wide variety of disorders that cause an increase in pulmonary capillary permeability.* Because of the importance of this syndrome as a major form of acute respiratory failure, Chapter 28 focuses entirely on the problem of ARDS.

Hypercapnic/Hypoxemic Type

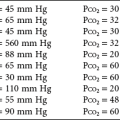

In the second category, hypercapnia is present. For the respiratory failure to be considered acute, the pH must show absent or incomplete metabolic compensation for the respiratory acidosis. From the discussion of alveolar gas composition and the alveolar gas equation in Chapter 1, it is apparent that hypercapnia is associated with decreased arterial PO2 because of altered alveolar PO2. Therefore, even if ventilation and perfusion are relatively well matched and the fraction of blood shunted across the pulmonary vasculature is not increased, arterial PO2 falls in the presence of hypoventilation and consequent hypercapnia. In fact, many cases of hypercapnic respiratory failure have marked ventilation-perfusion mismatch as well, which further accentuates the hypoxemia. With these concepts in mind, it is clear the hypercapnic form of respiratory failure generally involves not just hypercapnia; it may be more appropriately considered the hypercapnic/hypoxemic form of respiratory failure.

Pathogenesis of Gas Exchange Abnormalities

The basic principles of abnormal gas exchange were discussed in Chapter 1. The focus here is on applying these principles to patients with respiratory failure. A discussion of hypoxemic respiratory failure is followed by a discussion of hypercapnic/hypoxemic failure.

Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure

Alveolar filling with fluid and collapse of small airways and alveoli seem to be the main pathogenetic features leading to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and shunting in ARDS (see Chapter 28). An earlier consideration of the ability of supplemental O2 to raise PO2 in conditions of ventilation-perfusion mismatch versus shunt indicated that O2 cannot improve PO2 significantly for truly shunted blood (see Chapter 1). Therefore, when the shunt fraction of cardiac output is quite high, oxygenation may be helped surprisingly little by administration of supplemental O2.

Hypercapnic/Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure

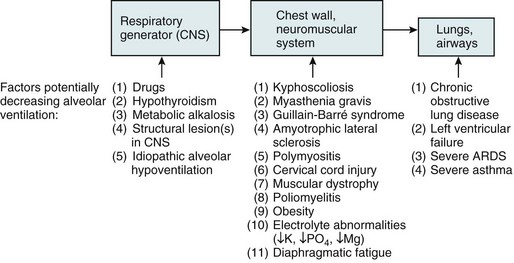

In the hypercapnic form of respiratory failure, patients are unable to maintain a level of alveolar ventilation sufficient to eliminate CO2 and keep arterial PCO2 within the normal range. Because ventilation is determined by a sequence of events ranging from generation of impulses by the respiratory controller to movement of air through the airways, there are multiple stages at which problems can adversely affect total minute ventilation. This sequence is shown in Figure 27-1, which also lists some of the disorders that can interfere at each level. Not only is the total ventilation per minute important, the “effectiveness” of the ventilation for CO2 excretion—that is, the relative amount of alveolar versus dead space ventilation—is also important to ensure proper utilization of inspired gas. If the proportion of each breath going to dead space (i.e., ratio of volume of dead space to tidal volume [VD/VT]) increases substantially, alveolar ventilation may fall to a level sufficient to cause elevated PCO2, even if total minute ventilation is preserved.

Given the causes of hypoxemia in the hypercapnic/hypoxemic form of respiratory failure, patients frequently respond to supplemental O2 with a substantial rise in arterial PO2. However, most of these patients have at least mild chronic CO2 retention, with their acute respiratory failure resulting from some precipitating insult or worsening of their underlying disease. Administration of supplemental O2 to these chronically hypercapnic patients may lead to a further increase in arterial PCO2 for a number of pathophysiologic reasons (see Chapter 18). With judicious use of supplemental O2, substantial additional elevation of arterial PCO2 can usually be avoided.

An elaboration of further features of the hypercapnic/hypoxemic form of respiratory failure follows.

Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Hypercapnic/Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure

The general therapeutic approach to these patients involves three main areas: (1) support of gas exchange, (2) treatment of the acute precipitating event, and (3) treatment of the underlying pulmonary disease. Support of gas exchange involves maintaining adequate oxygenation and elimination of CO2 (see Chapter 29). Briefly, supplemental O2, generally in a concentration only slightly higher than that found in ambient air, is administered to raise PO2 to an acceptable level (i.e., > 60 mm Hg). If CO2 elimination deteriorates much beyond the usual level of PCO2, then an acute respiratory acidosis is superimposed on the patient’s usual acid-base status. If significant acidemia develops or if the patient’s mental status changes significantly as a result of CO2 retention, some form of ventilatory assistance, either intubation and mechanical ventilation or noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation with a mask, may be required.

When patients with irreversible chest wall or neuromuscular disease are in frank respiratory failure, they may require some form of ventilatory assistance on a chronic basis (modalities for chronic ventilatory support are discussed in Chapter 29). It is important to emphasize here that the primary decision is whether chronic ventilatory support should be given to a patient with this type of irreversible disease. In many cases the patient, family, and physician make the joint decision that life should not be prolonged with chronic ventilator support, given the projected poor quality of life and irreversible nature of the process.

Chakrabarti, B, Calverley, PMA. Management of acute ventilatory failure. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:438–445.

Greene, KE, Peters, JI. Pathophysiology of acute respiratory failure. Clin Chest Med. 1994;15:1–12.

Krachman, S, Criner, GJ. Hypoventilation syndromes. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:139–155.

Levy, MM. Pathophysiology of oxygen delivery in respiratory failure. Chest. 2005;128(5 Suppl 2):547S–553S.

Rousso, C, Koutsoukou, A. Respiratory failure. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;47:3s–14s.

Weinberger, SE, Schwartzstein, RM, Weiss, JW. Hypercapnia. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1223–1231.

Younes, M, Mechanisms of ventilatory failure, Current pulmonology. Tierney, DF, eds. Current pulmonology. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1993;vol 14:243–292.

Respiratory Failure in Obstructive Lung Disease

Calverley, PM. Respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;47:26s–30s.

Davidson, AC. Critical care management of respiratory failure resulting from COPD. Thorax. 2002;57:1079–1084.

Phipps, P, Garrard, CS. Acute severe asthma in the intensive care unit. Thorax. 2003;58:81.

Plant, PK, Elliott, MW. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 9: Management of ventilatory failure in COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:537–542.

Robinson, TD, Freiberg, DB, Regnis, JA, et al. The role of hypoventilation and ventilation-perfusion redistribution in oxygen-induced hypercapnia during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1524–1529.

Respiratory Failure in Neuromuscular and Chest Wall Disease

Bergofsky, EH. Respiratory failure in disorders of the thoracic cage. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119:643–669.

Cabrera Serrano, M, Rabinstein, AA. Causes and outcomes of acute neuromuscular respiratory failure. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1089–1094.

Gracey, DR, Divertie, MB, Howard, FM, Jr. Mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure in myasthenia gravis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:597–602.

Gracey, DR, McMichan, JC, Divertie, MB, et al. Respiratory failure in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1982;57:742–746.

Howard, RS, Davidson, C. Long-term ventilation in neurogenic respiratory failure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(Suppl 3):iii24–30.

Mehta, S. Neuromuscular disease causing acute respiratory failure. Respir Care. 2006;51:1016–1021.

Seneviratne, J, Mandrekar, J, Wijdicks, EF, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in myasthenic crisis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:54–58.

Shneerson, JM, Simonds, AK. Noninvasive ventilation for chest wall and neuromuscular disorders. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:480–487.

Simonds, AK. Recent advances in respiratory care for neuromuscular disease. Chest. 2006;130:1879–1886.