CHAPTER 30 Chronic Unreduced Elbow Dislocation

INTRODUCTION

Elbow instability in one form or another remains one of the most vexing of all expressions of elbow trauma. The spectrum of elbow instability is carefully addressed in the pediatric patient (see Chapter 20), simple and complex instability in the adult (see Chapters 28 and 29), and in the chapter on external fixation for the elbow (see Chapter 33). The instability addressed in this chapter is termed chronic unreduced complete dislocation. A chronic unreduced dislocation is very uncommon in this country and is principally seen in Third World nations. Thus, much of our understanding has come from contributions from South Africa, Thailand, and India.8,10,11,14,17,18

CHRONIC UNREDUCED ELBOW JOINT

The simplest way to consider the two major types of chronic unreduced elbow joints is that of subluxation, or complete dislocation. The most common of these is sometimes a subtle chronic posterior subluxation due to fracture of the coronoid. This chronic instability pattern is dealt with in the chapter on complex instability (see Chapter 29). The chronically unreduced complete dislocation is not common, so few have much experience dealing with it. The second is an unreduced complete dislocation, which is rare except, as mentioned earlier, in underdeveloped countries.

PRESENTATION

Chronic unreduced complete dislocation has the following characteristics: (1) gross deformity; (2) variable motion from complete ankylosis in approximately one third of cases to a near-functional arc of motion of greater than 40 degrees in one third, and motion between 0 to 40 degrees in the remaining one third13; (3) pain ranges from minimal to significant depending on the duration of the dislocation with marked individual variation.

OCCURRENCE AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

At presentation, about two thirds have unacceptable function due to instability, pain, or both.13 The frequency is highly dependent on the local medical customs dealing with the initial dislocation, experience, expertise, and expectation. The presence of traditional medical care (bone setters3) explains the reports from Africa documenting large series (81 cases over a 10-year period).14 In Thailand, 135 patients were reported in a 15-year period from three hospitals.10 The deformity may occur both in children and in adults. These patients have often sustained an associated fracture as well. Naidoo14 noted that 13 of 23 patients undergoing treatment had an associated fracture. A similar rate of 45% (62 of 135) was reported from a large multicenter study by Mahaisavariya and associates.10 About 50% simply have a posteriorly displaced, complete dislocation. The patients usually do not have neurologic deficit at the time of presentation, but if there is neural impairment, the ulnar nerve is most commonly symptomatic. Vascular compromise is extremely rare.

TREATMENT

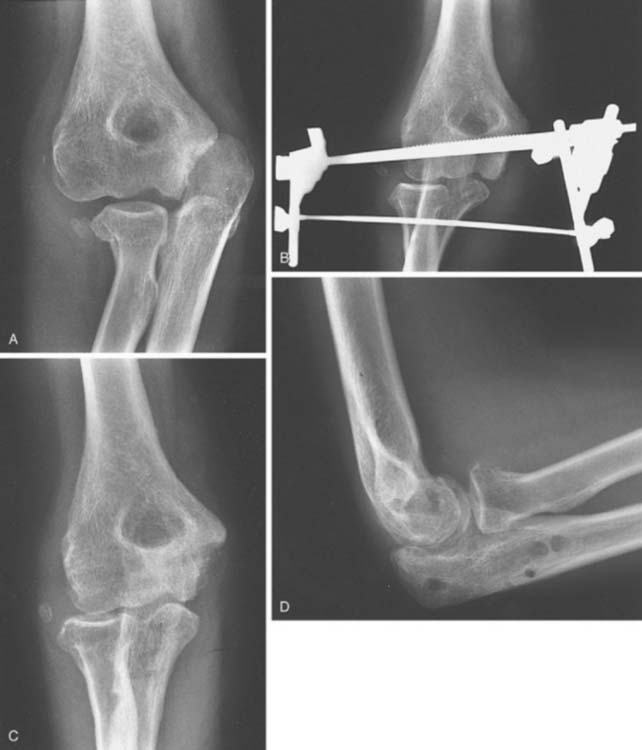

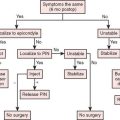

The choice of treatment has been predicated on the age of the patient, the timing of the intervention, and the likelihood of successful reduction. The full spectrum of reconstructive options has been suggested as a treatment for the neglected dislocation. These options include reduction, reduction and interposition, resection, fusion, and replacement. Resection is not a viable option today. In most practices and circumstances, fusion might be considered, but this is not usually considered in the United States. The techniques of interposition and replacement arthroplasty are discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 69 and 70). An attempt at closed reduction is reasonable at all ages for dislocations of less than 3 weeks’ duration. Today, this is particularly effective with the added stability provided by an external fixation.9,18 Although fusion and resection have both been considered for the chronic condition,2,4,6 by far the most logical and accepted approach is open reduction (Fig. 30-1). Although this recommendation has been somewhat controversial in the past, open reduction outcomes are as good or better than other options and is effective years after injury.5,11

Here we will review only the treatment strategy for open reduction. The use of an external fixation is discussed in Chapter 33. Joint replacement is recommended in patients older than 60 years of age and is discussed in Chapter 59. The surgical approach is predicated onan understanding of the pathology and a flexible surgical treatment plan.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

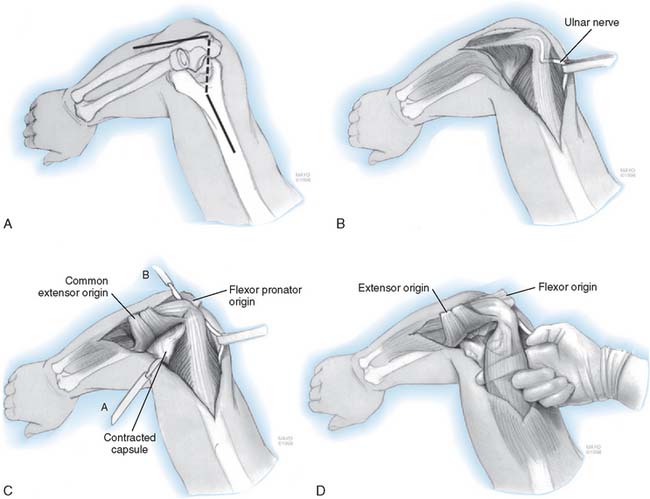

The surgical technique preferred by the author specifically addresses the pathology according to a defined sequence (Fig. 30-2).

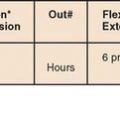

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The arm is elevated for 24 hours, after which continuous passive motion (CPM) is used. The patient returns home in a portable CPM with as much motion as tolerated. The external fixator is maintained for 3 to 4 weeks. The patient then returns to the hospital, and under a brief general anesthesia, the external fixator is removed and the elbow examined under fluoroscopy (see Chapter 33). Flexion and extension splints are then used to establish and maintain an arc of functional motion (see Chapter 11).

RESULTS

Naidoo14 described a satisfactory result in 23 of 25 patients treated in a manner similar to that just described but without a fixator. Arafiles1 described a satisfactory outcome in 11 of 12 surgical procedures. Open reduction was reported as successful in 72% of 52 patients by Di Schino and associates.5 Interestingly, these investigators also found complete resection of the elbow for the chronic cases to be successful in 80% of cases.4 However, careful interpretation of these two reports suggests that these authors are referring to improvement of motion and admitted that the resected elbow was weak and had marked instability, and hence, they favor reduction over resection.

MOTION

The improvement is marked, but a functional status is not always attained. Of the 23 patients reported by Naidoo14 with 13 associated fractures, eight patients remain with less than 60 degrees of motion (33%). Five had an arc of motion between 60 and 90 degrees (20%), and 10 (40%) had an arc of motion greater than 90 degrees. Naidoo also demonstrated that the overall outcome was not a function of age or duration of dislocation as had been previously thought. On the other hand, Arafiles1 reports a mean of 105 degrees arc at 2 years in a group of 11 patients. The most recent report from Bangkok documented a final arc of flexion of 82 degrees in 24 patients 4 years after surgery.11

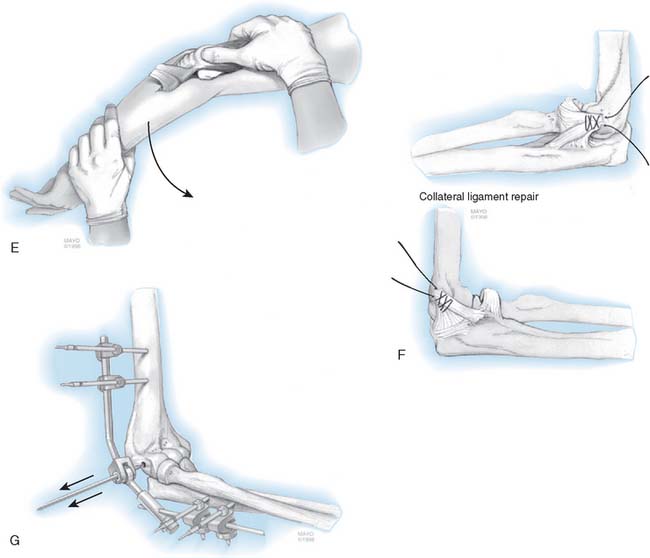

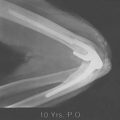

One major discussion in the literature relates to the management of the triceps. If operated on less than 3 months after injury, this generally need not be lengthened or addressed. However, as mentioned earlier, if the triceps is badly contracted and limits flexion, then some form of triceps augmentation and release is appropriate. Mahaisavariya and colleagues10 demonstrated that leaving the triceps intact was associated with increased motion (P > .05) of 115 degrees in those in which the triceps was not altered, compared with 89 degrees in those with triceps release. In addition, they demonstrated that the flexion contracture was markedly greater (by 70 degrees) in those with a tricepsplasty, compared with 45 degrees in patients in whom tricepsplasty was not carried out. If the triceps is addressed, V-Y lengthening as described by VanGorder has been suggested by some; however, as noted earlier, we prefer the anconeus slide technique. Overall, this approach has been effective even in those with considerable joint deformity (Fig. 30-3A to G)

COMPLICATIONS

This is difficult surgery, and as might be expected, this type of injury and surgery are associated with significant complications. Transient nerve injury has been reported in 8% to 40% of cases.7,14 Infection occurs in approximately 5%.1 Ectopic bone was reported in none of the 70 cases of Mahaisavariya and associates10 and none of the 23 cases of Naidoo.14 On the other hand, it was observed in 8% of the patients reported by Fowles and colleagues7 and one in four of the patients described by Billett.3 The overall complication rate is approximately 20% to 25%. Complications that significantly affect the outcome occur at a rate of at least 10%.

AUTHOR’S EXPERIENCE

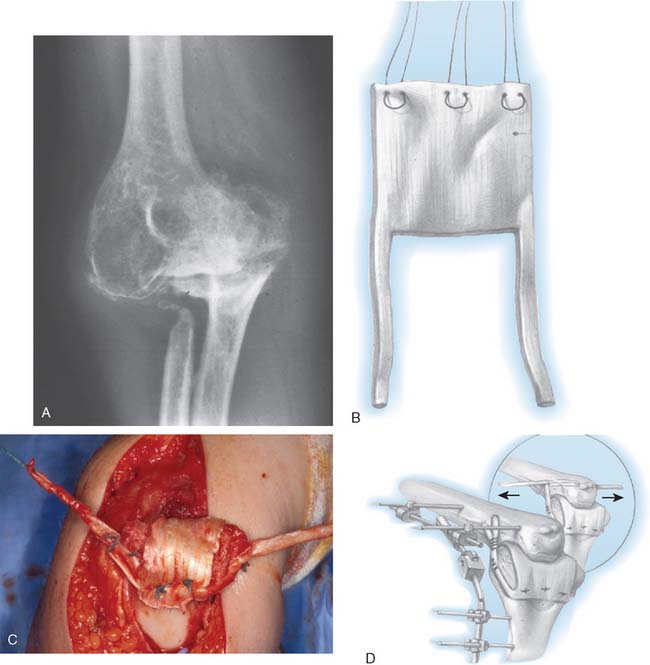

ELBOW REPLACEMENT

Because of the factors and prognosis noted previously, we prefer the reliable and functional outcome of elbow arthroplasty in patients older than 65 years of age. Experience with joint replacement in patients with gross instability has been reported by Ramsey and associates.16 A success rate of about 90 percent was documented a mean of 6 years after surgery (Fig. 30-4). Elbow replacement with complete ankylosis has been reported by Mansat and by Peden.12,15 Overall, an 80% satisfactory outcome at 6 years was documented.

CONCLUSIONS

Ideally, of course, chronic unreduced elbow dislocation is best managed by prevention. In the absence of prevention, most patients with unreduced elbow dislocations should be managed according to the principles and technique described here. If this methodology is followed, it is expected that approximately 60% to 75% of the patients have a satisfactory result, which includes minimal pain and an arc of motion equal or greater than 80 to 90 degrees. If the surgeon reconstructs the collateral ligaments or performs an interposition, an external fixation device is used. The complication rate is significant and varies as a function of the extent of the pathology, surgeon experience, and expertise. Finally, joint replacement is the treatment of choice for patients older than 65 years of age and affords a reliable salvage procedure.

1 Arafiles R.P. Neglected posterior dislocation of the elbow. A reconstruction operation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69B:199.

2 Ashby M.E. Old dislocations of the elbow. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1974;66:465.

3 Billett D.M. Unreduced posterior dislocation of the elbow. J. Trauma. 1979;19:186.

4 Di Schino M., Breda Y., Grimaldi F.M., Lorthioir J.M., Merrien Y. Resection of the distal part of the humerus in neglected elbow dislocations. Apropos of 23 case reports. Med. Trop. 1989;49:415.

5 Di Schino M., Breda Y., Grimaldi F.M., Lorthioir J.M., Merrien Y. Surgical treatment of neglected elbow dislocations. Report of 81 cases. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Repar. Appareil Moteur. 1990;76:303.

6 Dryer R.F., Buckwalter J.A., Sprague B.L. Treatment of chronic elbow instability. Clin. Orthop. 1980;148:254.

7 Fowles J.V., Kassab M.T., Douik M. Untreated posterior dislocation of the elbow in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:921.

8 Krishnamoorthy S., Bose K., Wong K.P. Treatment of old unreduced dislocation of the elbow. Injury. 1976;8:39.

9 Lo C.Y., Chang Y.P. Neglected elbow dislocation in a young man: Treatment by open reduction and elbow fixator. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:101.

10 Mahaisavariya B., Laupattarakasem W., Supachutikul A., Taesiri H., Sujaritbudhungkoon S. Late reduction of dislocated elbow. Need triceps be lengthened? J. Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B:426.

11 Mahaisavariya B., Laupattarakasem W. Neglected dislocation of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005;431:21.

12 Mansat P., Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for ankylosed and stiff elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82A:1260.

13 Martini M., Benselama R., Daoud A. Neglected luxations of the elbow: 25 surgical reductions. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Repar. Appareil Moteur. 1984;70:305.

14 Naidoo K.S. Unreduced posterior dislocations of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64B:603.

15 Peden J.P., Morrey B.F. Total Elbow Arthroplasty for the Management of the Ankylosed or Fused Elbow. Submitted for publication. Br. J. Surg. 2008.

16 Ramsey M., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Elbow displacement for gross instability. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81A:38-47.

17 Silva J.F. Old dislocations of the elbow. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1958;22:363.

18 Sunderamoorthy D., Smith A., Woods D.A. Recurrent elbow dislocation—an uncommon presentation. Emerg. Med. J. 2005;22:667.