Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) refers to chronic disorders that disturb airflow, whether the most prominent process is within the airways or within the lung parenchyma. The two disorders generally included in this category are chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although the pathophysiology of airflow obstruction is different in the two disorders, patients frequently have features of both, so it is appropriate to discuss them together. Asthma could logically also be in this category, but it is discussed in Chapter 5 because the term COPD, as commonly used, does not usually include bronchial asthma.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Smoking

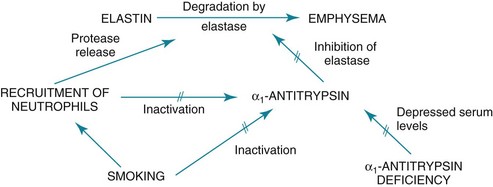

In smokers, the balance between elastase and anti-elastase is thought to be disturbed in more than one way by cigarette smoke. First, an increased number of neutrophils can be found in the lungs of smokers, providing a source for increased amounts of neutrophil elastase. Second, evidence indicates that oxidants derived from cigarette smoke and inflammatory cells can oxidize a critical amino acid residue of α1-antitrypsin at or near the site where the protease inhibitor binds to elastase. Oxidation of this amino acid interferes with the inhibitory activity of α1-antitrypsin, again tipping the balance in favor of increased elastase activity. Hence, cigarette smoking may be a compound insult, increasing the amount of neutrophil elastase in the lung and decreasing the normal inhibitory mechanism that serves to limit uncontrolled elastin breakdown by the enzyme. This pathogenetic sequence hypothesized for the development of emphysema is summarized in Figure 6-1.

Pathology

Much of the pathology in chronic bronchitis relates to mucus and the mucus-secreting apparatus in the airways. Mucus-secreting glands and goblet cells are responsible for production of bronchial secretions, but the mucous glands are the more important source (see Chapter 4). In chronic bronchitis, enlargement (hypertrophy and hyperplasia) of the mucus-secreting glands has been objectively assessed by comparing the relative thickness of the mucous glands with the total thickness of the airway wall. This ratio, known as the Reid index, is increased in patients with chronic bronchitis. In general, the number of goblet cells in the airways is increased as well, and these particular cells are abundant in airways more peripheral than usual. These alterations in the mucus-secreting apparatus increase the quantity of airway mucus, and its composition is likely altered as well. In practice, the secretions found in patients often are thick and more viscous than usual. Bronchial walls demonstrate evidence of an inflammatory process, with cellular infiltration and variable degrees of fibrosis.

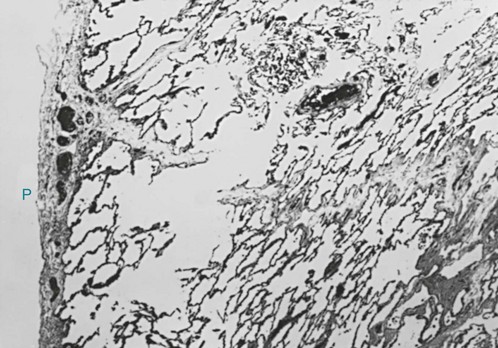

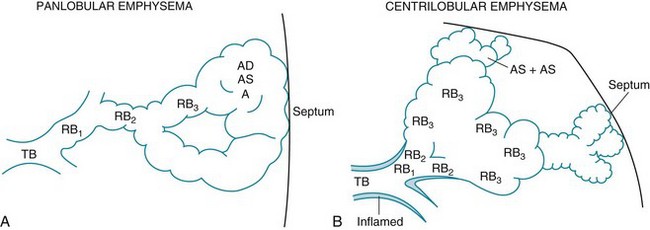

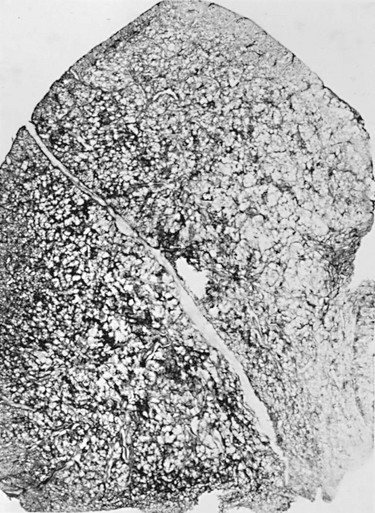

In patients with severe chronic airflow obstruction, the most important process responsible for airflow obstruction is emphysema. As mentioned earlier, the pathology of emphysema is characterized by destruction of alveolar walls and enlargement of terminal air spaces (Fig. 6-2). Several types of emphysema have distinct pathologic features, primarily dependent on the distribution of the lesions. The most important types are panacinar (panlobular) emphysema and centriacinar (centrilobular) emphysema (Fig. 6-3). Panacinar emphysema is characterized by a relatively uniform involvement of the acinus, the region beyond the terminal bronchiole, including respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs. Examination of a section of lung with panacinar emphysema shows that the damage in an involved area is relatively diffuse (Fig. 6-4). Typically the lower zones of the lung are more involved than the upper zones. Panacinar emphysema is the usual type of emphysema described in patients who have α1-antitrypsin deficiency, although the condition is not limited to this clinical setting.

In centrilobular emphysema, the predominant involvement and dilation are found in the proximal part of the acinus, the respiratory bronchiole. The appearance of a lung section with centrilobular emphysema is different from that with panacinar emphysema. In centrilobular emphysema, involvement in an affected area seems to be more irregular, with apparently spared alveolar tissue between the dilated respiratory bronchioles at the center of the acinus (Fig. 6-5). This type of emphysema is the typical form seen in smokers. It is reasonable to speculate that the prominent involvement focused around the respiratory bronchiole is a consequence of extension of the bronchiolar inflammation in mild COPD.

Pathophysiology

Functional Abnormalities in Airways Disease

Before a discussion of how lung volumes change in patients having the airway disease associated with COPD, it is useful to review the factors that determine major lung volumes: total lung capacity (TLC), functional residual capacity (FRC), and residual volume (RV). TLC is the point at which the force of the inspiratory muscles acting to expand the lungs is equaled by the elastic recoil of the respiratory system (primarily lung recoil) resisting expansion (see Chapter 1). At FRC, the resting point of the respiratory system, there is a balance between the elastic recoil of the lungs and the elastic recoil of the chest wall, which are acting in opposite directions—the lungs inward and the chest wall outward. The determinants of RV depend to some extent on age. In a normal young person, RV is the point at which the relatively stiff chest wall can be compressed no further by the expiratory muscles. With increasing age, a sufficient number of airways close at low lung volumes to limit further expiration, and airway closure is an important determinant of RV. In disease states in which airways are likely to close at low lung volumes, airway closure is associated with an elevated RV, even in young patients.

Functional Abnormalities in Emphysema

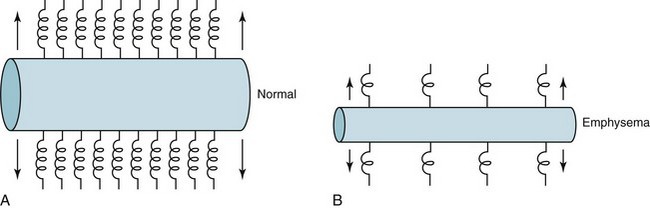

Loss of driving pressure is not the only consequence of emphysema. There is also an indirect effect on the collapsibility of airways. Normally, outward traction is exerted on the walls of airways by a supporting structure of tissue from the lung parenchyma. When the alveolar tissue is disrupted, as in emphysema, the supporting structure for the airways is diminished, and less radial traction is exerted to prevent airway collapse (Fig. 6-6). During a forced expiration, the strongly positive pleural pressure promotes collapse. Airways lacking an adequate supporting structure are more likely to collapse (and have diminished flow rates and air trapping) than normally supported airways.

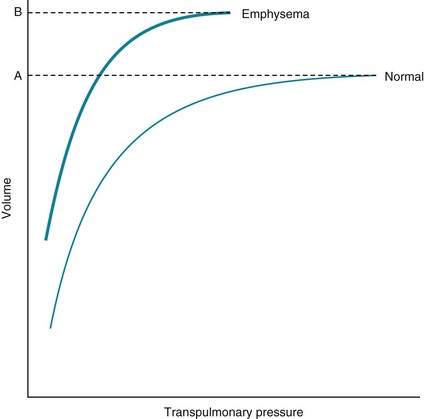

The decrease in elastic recoil in emphysema also alters the compliance curve of the lung and measured lung volumes. The compliance curve relates transpulmonary pressure and the associated volume of gas within the lung (see Chapter 1). Because an emphysematous lung has less elastic recoil (i.e., is less stiff), it resists expansion less than its normal counterpart, the compliance curve is shifted upward and to the left, and the lung has more volume at any particular transpulmonary pressure (Fig. 6-7). TLC is increased because loss of elastic recoil results in a smaller force opposing the action of the inspiratory musculature. FRC is also increased because the balance between the outward recoil of the chest wall and the inward recoil of the lung is shifted in favor of the chest wall. As in bronchitis, RV is substantially increased in emphysema because poorly supported airways are more susceptible to closure during a maximal expiration.

Mechanisms of Abnormal Gas Exchange

An additional problem, fatigue of inspiratory muscles, has received attention as a factor contributing to acute CO2 retention when affected patients are in respiratory failure (see Chapter 19). The importance of diaphragmatic fatigue in the stable patient with chronic hypercapnia is less certain. However, it is clear that contraction of the diaphragm, the major muscle of inspiration, is less efficient and less effective in patients with obstructive lung disease. When FRC is increased, the diaphragm is lower and flatter, and its fibers are shortened even before the initiation of inspiration. A shortened, flattened diaphragm is at a mechanical disadvantage compared with a longer, curved diaphragm, and it is less effective as an inspiratory muscle.

Pulmonary Hypertension

A potential complication of COPD is development of pulmonary hypertension (i.e., high pressures within the pulmonary arterial system). Long-standing pulmonary hypertension places an added workload onto the right ventricle, which hypertrophies and eventually may fail. The term cor pulmonale is used to describe disease of the right ventricle secondary to lung disease (either COPD or other forms of lung disease); this topic is discussed in Chapter 14. The primary feature of COPD that leads to pulmonary hypertension and eventually to cor pulmonale is hypoxia. A decrease in PO2 is a strong stimulus to constriction of pulmonary arterioles (see Chapter 12). If hypoxia is corrected, the element of pulmonary vasoconstriction may be reversible, but vascular remodeling from chronic hypoxia may not fully reverse.

Clinical Features

Frequently patients have a certain level of chronic symptoms, but their disease course is punctuated by periods of exacerbation. An exacerbation is defined as an acute event characterized by worsening of symptoms that requires a change in medication. The precipitating factor producing an exacerbation is often a respiratory tract infection, particularly of viral origin. In addition, bacteria may be chronically present in the tracheobronchial tree, which normally should be sterile, and an acute bacterial infection, often due to acquisition of a new strain of the colonizing bacteria, can sometimes be implicated in acute exacerbations. Other factors that cause acute deterioration in patients include exposure to air pollutants, bronchospasm (particularly if patients have a superimposed asthmatic component to their disease), and congestive heart failure. However, in up to a third of cases, the cause of an exacerbation cannot be identified. When exacerbations are severe, patients may go into frank respiratory failure, a complication discussed in Chapter 27.

In advanced COPD, patients may use accessory muscles of respiration (e.g., sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles), and the intercostal muscles may retract with each inspiration. The patient may assume a characteristic “tripod” position, leaning forward on straight arms allowing fixation of the clavicles and more effective use of accessory muscles. Severe disease may also be complicated by weight loss and muscle wasting. When cor pulmonale is present, with or without frank right ventricular failure, patients have the cardiac findings described in Chapter 14.

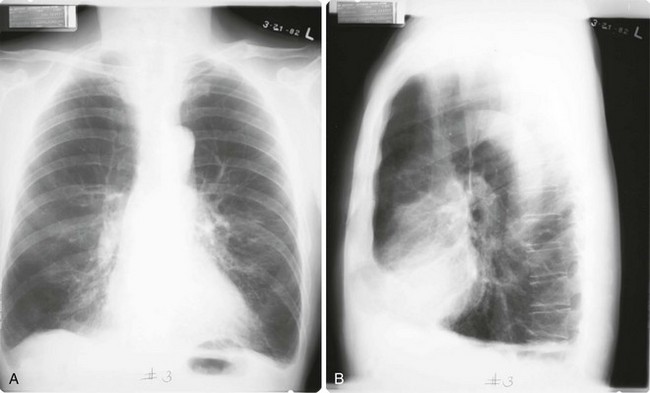

Diagnostic Approach and Assessment

Chest radiographs have poor sensitivity in detecting COPD but are valuable in excluding other processes that cause dyspnea, such as congestive heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis, or pleural disease. Patients with chronic bronchitis alone frequently have a normal chest radiograph. When present, chest radiographic findings suggestive of COPD include signs of hyperinflation such as large lung volumes, flat diaphragms, an increased retrosternal air space, increased anteroposterior diameter (seen on the lateral view), and a paucity of vascular markings. Hyperinflation associated with decreased vascular markings in the lungs results from destruction of alveolar septa and enlargement of alveolar spaces and has been called the arterial deficiency pattern of emphysema (Fig. 6-8). In patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency and early onset of emphysema, the arterial deficiency pattern is quite striking in the lower lobes, where there may be almost a complete loss of vascular markings.

Treatment

Several modalities of treatment, used either individually or in combination, are available for patients with COPD. Although bronchoconstriction in these patients is considerably less than in patients with bronchial asthma, bronchodilators remain an important part of the treatment of many COPD patients. The agents used are identical to those discussed in Chapter 5, including sympathomimetic agents (β2 agonists), anticholinergic drugs, and methylxanthines. Short-acting inhaled β2 agonists (e.g., albuterol), short-acting anticholinergic agents (e.g., ipratropium), or both are most commonly used as needed for patients with mild disease who require only infrequent therapy. For patients with more severe disease who require regular therapy, either a long-acting β2 agonist (e.g., salmeterol, formoterol, arformoterol), a long-acting anticholinergic agent (e.g., tiotropium), or both are commonly used, although regular use of short-acting agents is an alternative. The methylxanthine theophylline is another option, but concern for systemic side effects often relegates it to a secondary role in comparison with the inhaled bronchodilators.

When acute respiratory failure supervenes as a part of COPD, mechanical ventilation may be necessary to support gas exchange and maintain acceptable arterial blood gas values. Such ventilatory assistance with intermittent positive pressure may be delivered via either a mask (noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation) or an endotracheal tube. More detailed information about the treatment of acute respiratory failure superimposed on chronic disease of the obstructive variety is covered in Chapter 27. Mechanical ventilation is discussed in Chapter 29.

Balkissoon, R, Lommatzsch, S, Carolan, B, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a concise review. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:1125–1141.

Celli, BR, MacNee, W, ATS/ERS Task Force: Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD. a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–946.

Decramer, M, Janssens, W, Miravitlles, M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1341–1351.

2011. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). http://www.goldcopd.org/, 2011. Available from (Accessed 18 June 2012)

Silverman, EK, Sandhaus, RA. Clinical practice. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2749–2757.

Antó, JM, Vermeire, P, Vestbo, J, et al. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:982–994.

Brusselle, GG, Joos, GF, Bracke, KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378:1015–1026.

Carrell, RW, Lomas, DA. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency—a model for conformational diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:45–53.

Cosio, MG, Saetta, M, Agusti, A. Immunologic aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2445–2454.

Criner, GJ, Cordova, F, Sternberg, AL, et al. Part I: Lessons learned about emphysema. The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:763–770.

Djukanovic, R, Gadola, SD. Virus infection, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2062–2064.

Eisner, MD, Anthonisen, N, Coultas, D, et al. An official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:693–718.

Hurst, JR, Vestbo, J, Anzueto, A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138.

Lamela, J, Vega, F. Immunologic aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1024.

Martinez, CH, Han, MK. Contribution of the environment and comorbidities to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:713–727.

McDonough, JE, Yuan, R, Suzuki, M, et al. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1567–1575.

Sethi, S, Murphy, TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355–2365.

Smolonska, J, Wijmenga, C, Postma, DS, et al. Meta-analyses on suspected chronic obstructive pulmonary disease genes: a summary of 20 years’ research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:618–631.

Stoller, JK, Aboussouan, LS. A review of α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:246–259.

Tashkin, DP. Frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—a distinct phenotype? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1183–1184.

Tuder, RM, Petrache, I. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2749–2755.

van den Berge, M, ten Hacken, NH, Cohen, J, et al. Small airway disease in asthma and COPD: clinical implications. Chest. 2011;139:412–423.

Wan, ES, Silverman, EK. Genetics of COPD and emphysema. Chest. 2009;136:859–866.

Barr, RG, Bluemke, DA, Ahmed, FS, et al. Percent emphysema, airflow obstruction, and impaired left ventricular filling. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:217–227.

Celli, BR, Barnes, PJ. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1224–1238.

Currie, GP, Legge, JS. ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Diagnosis. BMJ. 2006;332:1261–1263.

Laurin, C, Moullec, G, Bacon, SL, et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:918–923.

Mannino, DM, Watt, G, Hole, D, et al. The natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:627–643.

Nussbaumer-Ochsner, Y, Rabe, KF. Systemic manifestations of COPD. Chest. 2011;139:165–173.

Peinado, VI, Pizarro, S, Barberà, JA. Pulmonary vascular involvement in COPD. Chest. 2008;134:808–814.

Sapey, E, Stockley, RA. COPD exacerbations. 2: Aetiology. Thorax. 2006;61:250–258.

Barr, RG, Bourbeau, J, Camargo, CA, et al. Tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2006;61:854–862.

Casaburi, R, ZuWallack, R. Pulmonary rehabilitation for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1329–1335.

Criner, GJ. Alternatives to lung transplantation: lung volume reduction for COPD. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:379–397.

Criner, GJ, Cordova, F, Sternberg, AL, et al. The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT). Part I: Lessons learned about emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:763–770.

Drummond, MB, Dasenbrook, EC, Pitz, MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2407–2416. 2008

Hansel, TT, Barnes, PJ. New drugs for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009;374:744–755.

Hays, JT, Ebbert, JO. Varenicline for tobacco dependence. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2018–2024.

Mackay, AJ, Hurst, JR. COPD exacerbations: causes, prevention, and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:789–809.

Michalski, JM, Golden, G, Ikari, J, et al. PDE4: a novel target in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:134–142.

Niewoehner, DE. Clinical practice. Outpatient management of severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1407–1416.

Qaseem, A, Wilt, TJ, Weinberger, SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. American College of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179–191.

Ranney, L, Melvin, C, Lux, L, et al. Systematic review: smoking cessation intervention strategies for adults and adults in special populations. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:845–856.

Ries, AL, Bauldoff, GS, Carlin, BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131:4S–42S.

Rodrigo, GJ, Castro-Rodriguez, JA, Plaza, V. Safety and efficacy of combined long-acting beta-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids vs long-acting beta-agonists monotherapy for stable COPD: a systematic review. Chest. 2009;136:1029–1038.

Sciurba, FC, Ernst, A, Herth, FJ, et al. A randomized study of endobronchial valves for advanced emphysema. VENT Study Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1233–1244.

Singh, S, Amin, AV, Loke, YK. Long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:219–229.

Singh, S, Loke, YK, Furberg, CD. Inhaled anticholinergics and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:1439–1450.

Stoller, JK, Panos, RJ, Krachman, S, et al. current evidence and the long-term oxygen treatment trial. Long-term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group. Oxygen therapy for patients with COPD. Chest. 2010;138:179–187.

Tonnesen, P, Carrozzi, L, Fagerström, KO, et al. Smoking cessation in patients with respiratory diseases: a high priority, integral component of therapy. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:390–417.

Vogelmeier, C, Hederer, B, Glaab, T, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. POET-COPD Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1093–1103.

Wedzicha, JA. Choice of bronchodilator therapy for patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1167–1168.

Wenzel, RP, Fowler, AA III, Edmond, MB. Antibiotic prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:340–347.

mismatch and hypoxemia.

mismatch and hypoxemia. mismatch

mismatch