Chapter 27 Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

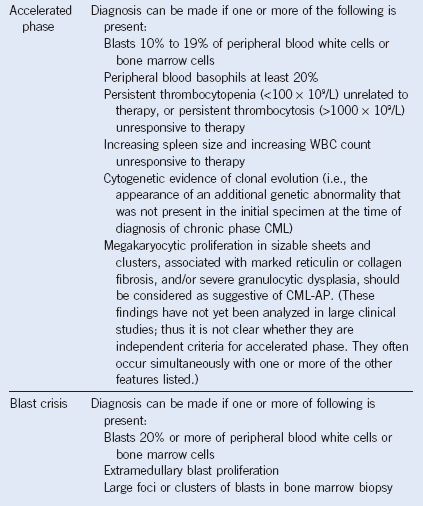

Management of the Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patient

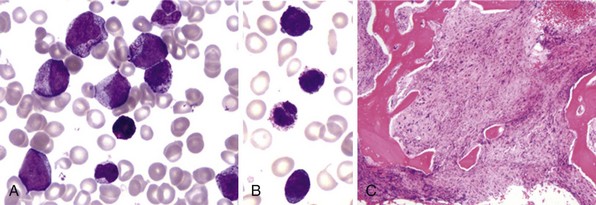

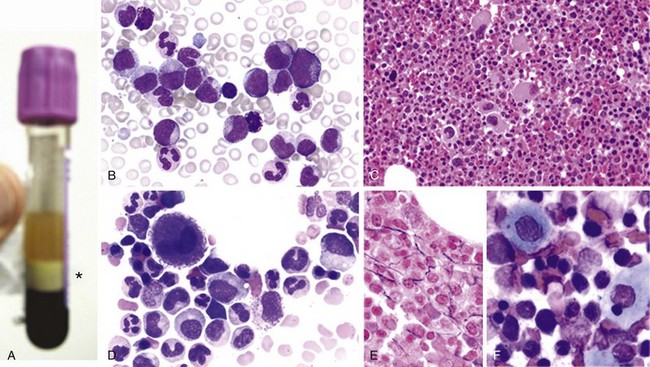

Figure 27-1 CHRONIC MYELOGENOUS LEUKEMIA, PERIPHERAL BLOOD TUBE, AND IMAGES OF BLOOD SMEAR AND BONE MARROW BIOPSY AND ASPIRATE IN CHRONIC PHASE.

| Hematologic Response | Cytogenetic Response | Molecular Response |

|---|---|---|

| Complete: Platelet count <450 × 109/L; WBC count <10 × 109/L; differential without immature granulocytes and with less than 5% basophils; nonpalpable spleen | Complete: Ph+ 0 Major: Ph+ 1%-35% Minor: Ph+ 36%-65 Minimal: Ph+ 66%-95% None: Ph+ <95% |

Complete: BCR-ABL transcripts nonquantifiable and nondetectable* Major: ≤0.10% |

BCR-ABL to control gene ratio according to the proposed international scale for measuring molecular response, with a standardized “baseline,” as established in the IRIS trial, taken to represent 100% on the international scale, and a 3-log reduction from the standardized baseline (MMR) fixed at 0.10%.

*Qualified by the limit of sensitivity of the PCR assay employed.

Can Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Treatment Cure Chronic Myeloid Leukemia?

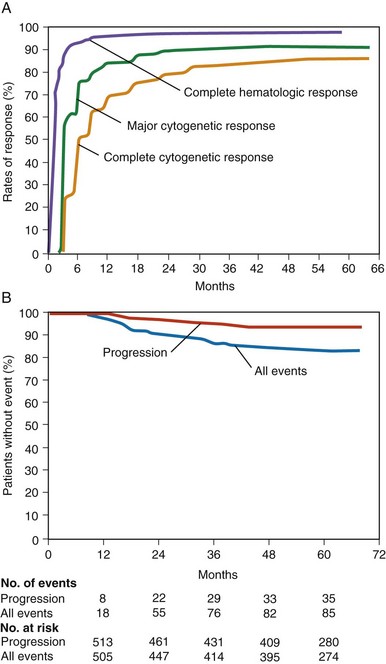

Figure 27-4 RESPONSE OF NEWLY DIAGNOSED CHRONIC MYELOID LEUKEMIA (CML) PATIENTS TO IMATINIB MESYLATE BASED ON 5 YEARS’ FOLLOW-UP ON THE INTERNATIONAL RANDOMIZED INTERFERON AND STI571 (IRIS) STUDY.

(Data from Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al: Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia, N Engl J Med 355:2408, 2006.)

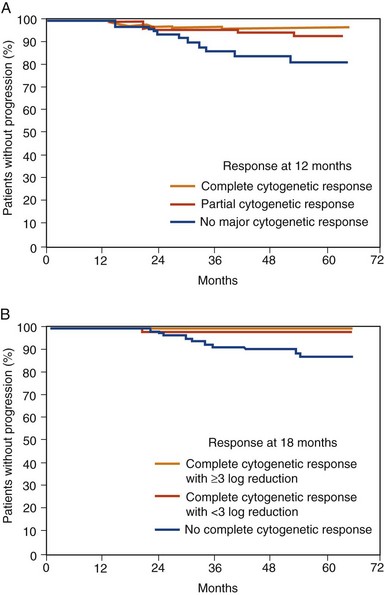

Figure 27-5 EVENT FREE SURVIVAL (EFS) OF NEWLY DIAGNOSED CHRONIC MYELOID LEUKEMIA (CML) PATIENTS TREATED WITH IMATINIB MESYLATE AFTER 7 YEARS’ FOLLOW-UP ON THE INTERNATIONAL RANDOMIZED INTERFERON AND STI571 (IRIS) STUDY BASED ON MOLECULAR RESPONSE AT 6- (A), 12- (B), AND 18-MONTH (C) LANDMARKS.

(Data from Hughes TP, Hochhaus A, Branford S, et al: Long-term prognostic significance of early molecular response to imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: An analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS), Blood 116:3758, 2010.)