Chapter 32 Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Initial Evaluation of Young Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

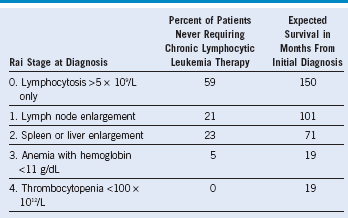

Adapted from Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, et al. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Blood 46:219, 1975.

Table 32-2 Evaluation of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients at Diagnosis

| History |

|---|

BM, Bone marrow; CBC, complete blood count; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CT, computed tomography; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LFT, liver function test; PET, positron emission tomography.

How Should Staging and Biomarkers Be Used for Treatment Decisions in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients?

Our understanding of the biology of CLL has improved dramatically, and many relevant biomarkers are now becoming useful for predicting when CLL will clinically progress. However, no study to date has demonstrated that earlier treatment will alter the natural history of the patient in even the higher risk groups with high progression rates. Therefore, at the present time, the use of staging and predictive biomarkers should be used only to provide patients with information relative to the expected course of their disease. Outside of a clinical trial, these results should never be used to initiate therapy in patients with asymptomatic disease and no indication for treatment. Before performing predictive tests, a detailed discussion of how these tests will be used with the patient should occur and the option of not performing them should be provided. In a subset of patients, significant anxiety can be produced by identifying high-risk features for which observation, without therapeutic intervention, remains the standard of care. Table 32-2 provides an example of the initial evaluation provided by our group when seeing a newly diagnosed patient. Because lymphocyte-doubling time is a prognostic feature in the progression of CLL, our approach is to follow patients every 3 months during the first year; if little change in clinical or laboratory parameters occurs at this point, we extend this time period to every 6 months in the absence of new complaints.

Table 32-3 Modified Indications for Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

AIHA, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; WBC, white blood cell.