36 Chorea

Etiology

Chorea results from disruption of the basal ganglia’s modulation of thalamocortical motor pathways. Multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms may be implicated. These include neuronal degeneration in selective regions, neurotransmitter receptor blockade, other metabolic factors within the basal ganglia, and exceedingly rarely a structural lesion. Chorea is classified into inherited, primarily Huntington disease (HD), immunologic Sydenham chorea, drug-related, structural, and various miscellaneous etiologies (Table 36-1).

| Type of Chorea | |

|---|---|

| Inherited | |

Clinical Presentation

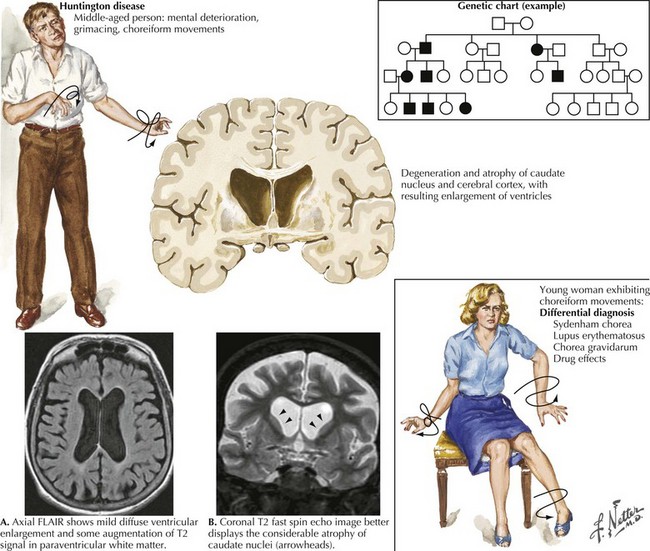

Huntington Disease

This hereditary, progressive neurodegenerative disorder is the most common cause of chorea. The classic signs of HD include the development of chorea, neurobehavioral changes, and gradual dementia (Fig. 36-1). Symptoms typically become evident during the fourth or fifth decade of life, although onset varies from early childhood to late adulthood. HD symptoms vary among patients in range and severity, as well as by age at onset, and in rate of clinical progression. An early onset is associated with increased severity and more rapid progression. For example, adult-onset HD typically lasts approximately 15–20 years, whereas the course of juvenile HD tends to last approximately 8–10 years.

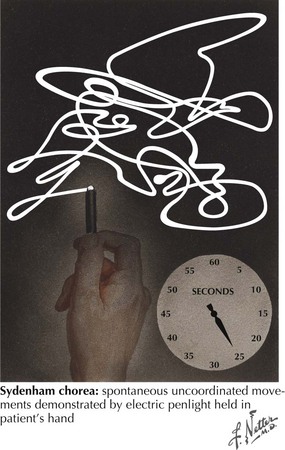

Sydenham Chorea

This is the other well-recognized form of chorea. It is related to an autoimmune response to infection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci leading to acute rheumatic fever (ARF). This is now very uncommon in economically developed countries with the widespread availability of antibiotics for Streptococcus A infection. The initial illness is usually characterized by pharyngitis, followed within approximately 1–5 weeks by the sudden onset of ARF. Chorea primarily occurs in patients between the ages of 5 and 15 years. It usually does not present until 1–6 months after the initial sore throat. Sydenham chorea may occur as an isolated condition or subsequent to other characteristic features of ARF. Initially, these children often are described as unusually restless, aggressive, or “excessively emotional.” The distribution of chorea is usually generalized, and these movements consist of relatively fast or rapid, irregular, uncontrollable, jerky motions that disappear with sleep and may increase with stress, fatigue, and excitement (Fig. 36-2). Occasionally, the choreiform movements are so severe that they have a ballistic character. Some children also evidence emotional and behavioral disturbances.

Differential Diagnoses

Diagnostic considerations in a patient presenting with chorea is a broad one (Table 36-1). HD, the most common cause of chorea, is usually easily diagnosed when an adult has the typical triad of chorea, dementia, and family history. Several neurodegenerative disorders, some also having expanded trinucleotide repeats, are phenocopies of HD. These include spinocerebellar atrophy (SCA2, SCA3) and dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Additionally, there are some other HD-like diseases (HDL1, HDL2, HDL3) that may present with an HD-like phenotype. Sydenham chorea has an earlier onset, lacks the characteristic mental disturbances, and is usually self-limiting. Chorea with mental dysfunction may also occur as a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). These patients usually have a more acute onset, with more localized chorea, and the characteristic SLE clinical and serologic abnormalities. There is a prior history of recurrent vascular thromboses or spontaneous abortions and disappearance after therapy with prednisone.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Huntington Disease

The evaluation of patients with chorea includes detailed family history and tests to exclude other possible pathophysiology (Box 36-1). Genetic testing is the most accurate test for HD. The mutation that is responsible for the disease consists of an unstable enlargement of the CAG repeat sequence. The gene is located at 4p16.3 and encodes for a protein called huntingtin.

Adam OR, Jankovic J. Symptomatic treatment of Huntington disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008 Apr;5(2):181-197.

Fahn S, Jankovic J. Huntington’s Disease. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2007:369-392.

Hersch SM, Rosas HD. Neuroprotection for Huntington’s disease: ready, set, slow. Neurotherapeutics. 2008 Apr;5(2):226-236.

Huntington Study Group. Tetrabenazine as antichorea therapy in Huntington disease: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2006 Feb 14;66(3):366-372.

Jankovic J, Beach J. Long-term effects of tetrabenazine in hyperkinetic movement disorders. Neurology. 1997;48:358-362.

O’Brien CH. Chorea. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E, editors. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:357-364.