2 Choosing the Correct Peel for the Appropriate Patient

Introduction

Chemical peels are a method of resurfacing the skin. By inducing a controlled wound to the skin, chemical peels replace part or all of the epidermis and can induce collagen remodeling which helps to improve photodamage, rhytides, pigmentation abnormalities, and scarring. Chemical peels are divided into three categories depending upon the depth of the wound created by the peel (Boxes 2.1 and 2.2). Superficial chemical peels penetrate the epidermis only, while medium-depth peels damage the entire epidermis plus the papillary dermis to the level of the upper reticular dermis. Deep chemical peels create a wound to the level of the mid-reticular dermis. Each category of peel addresses a different aspect of photodamage and pigmentary abnormality. Healing time and complications vary among the different categories of peel as well, with some peels being more appropriate for certain skin types. Therefore, in order to maximize the benefits of a peel for a patient and to minimize adverse effects, it is important to choose which, if any, peel is appropriate for each patient. See also Box 2.3.

Evaluation of the Patient

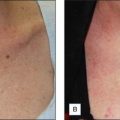

The physician should also perform a physical examination and pay particular attention to the patient’s skin type and degree of photodamage. Skin type can be classified using both the Glogau photoaging classification and the Fitzpatrick skin type scale (Box 2.4 and Table 2.1). Together, these skin classification systems can be used to objectively assess the patient’s skin and are an important component in choosing the appropriate peel. The Glogau photoaging classification system is used to quantify photodamage. Patients with Glogau type I skin would benefit most from a superficial peel, while those with Glogau type IV skin would benefit from deep peels. The Fitzpatrick skin type scale can be used to predict how a patient’s pigmentation will respond to each specific chemical peel. Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II can usually be treated with all chemical peels safely and successfully, while care must be taken in those patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III to VI, since patients with these skin types have a much higher risk of developing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH; Fig. 2.1).

Box 2.4

Glogau’s classification of photoaging

Adapted from Glogau RG 1994 Chemical peeling and aging skin. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology 2(1):30–35; Glogau RG 1996 Aesthetic and anatomic analysis of the aging skin. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 15(3):134–138

Table 2.1 Fitzpatrick’s classification of sun-reactive skin types

| Skin type | Color | Reaction to first summer exposure |

|---|---|---|

| I | White | Always burn, never tan |

| II | White | Usually burn, tan with difficulty |

| III | White | Sometimes mild burn, tan average |

| IV | Moderate brown | Rarely burn, tan with ease |

| V | Dark brown* | Very rarely burn, tan very easily |

| VI | Black | No burn, tan very easily |

* Asian Indian, Oriental, Hispanic, or light African descent, for example

Superficial Chemical Peels

Superficial peels can be categorized further into ‘very light’ and ‘light’ peels. See Box 2.5.

• Very light chemical peels

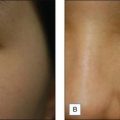

While a single treatment of a very superficial peel can induce exfoliation, a series of these peels is necessary in order to achieve additional benefit. Improvement of skin texture, through the removal of the stratum corneum, induction of acanthosis and an increase in thickness of the granular layer, as well as improvement of melasma and solar lentigenes can be achieved through a series of very superficial peels (Fig. 2.2). PIH is not common with superficial peels as they create minimal inflammation, but can occur.

• Light chemical peels

Although very light and light peels can be used in virtually all skin types, caution must still be taken in patients with darker skin, specifically Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI (see Table 2.1). A thorough knowledge of the subtleties of these chemical peels will allow the practitioner the ability to treat all skin types safely and effectively.

Ahn HH, Kim IH. Whitening effect of salicylic acid peels in Asian patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:372-375.

Briden ME. Alpha-hydroxy acid chemical peeling agents: case studies and rationale for safe and effective use. Cutis. 2004;73(2 Supply):18-24.

Brody HJ. Chemical Peeling and Resurfacing, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1997.

Buter PE, Gonzalez S, Randolph MA, et al. Quantitative and qualitative effects of chemical peeling on photo-aged skin: an experimental study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;107(1):222-228.

El-Domati MB, Attia SK, Saleh FY, et al. Trichloracetic acid peeling versus dermabrasion: a histometric, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural comparison. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:179-188.

Glogau RG, Matarasso SL. Chemical peels. Trichloroacetic acid and phenol. Dermatologic Clinics. 1995;13(2):263-276.

Halaas YP. Medium depth peels. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2004;12(3):297-303.

Hantash BM, Stewart DB, Cooper ZA, Rehmus WE. Facial resurfacing for nonmelanoma skin cancer prophylaxis. Archives of Dermatology. 2006;142:976-982.

Landau M. Cardiac complications in deep chemical peels. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:190-193.

Monheit GD, Chastain MA. Chemical and mechanical skin resurfacing. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RR, editors. Dermatology. St Louis: Mosby; 2003:2379-2396.

Monheit GD. Medium-depth chemical peels. Dermatologic Clinics. 2001;19(3):413-425.

Resnik SS, Resnik BI. Complications of chemical peeling. Dermatologic Clinics. 1995;13(2):309-312.

Stone PA, Lefer LG. Modified phenol chemical face peels. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2001;9(9):351-376.

Tse Y, Ostad A, Lee HS, et al. A clinical and histologic evaluation of two medium-depth peels: glycolic acid versus Jessner’s trichloroacetic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 1996;22(9):781-786.