CHAPTER 20 Child Maltreatment: Developmental Consequences

In the 21st century, child maltreatment continues to be a major medical, psychological, social, and public health issue that affects almost a million children every year in the United States. It is a problem that crosses all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic boundaries and affects not only the victims but also their families and their communities.

Child maltreatment has been defined by the Federal Abuse Reporting Act of 1974 as “the physical or mental injury, sexual abuse or exploitation, negligent treatment, or maltreatment of a child by a person who is responsible for the child’s welfare under circumstances which indicate harm or threaten harm to the child’s health or welfare.”1 Helfer, a pediatrician who was one of the coauthors with Kempe and others of the seminal article on child abuse entitled, “The Battered Child,”2 provided a definition that highlights the core elements of child maltreatment that are essential to the identification and appropriate treatment of these children. He defined child maltreatment as “any interaction or lack of interaction between family members which results in nonaccidental harm to the individual’s physical and/or developmental status.”3

There is currently no absolute checklist or set of symptoms or injuries by which clinicians can validly and reliably predict or verify that abuse or neglect has occurred to a child. There are certain physical findings that are known to be the result of inflicted injuries, such as spiral fractures of the femur in very young children, “bucket handle” fractures,4 and immersion burns. In addition, professionals should be aware of situations that are frequently associated with valid abusive or neglectful incidents. These are situations in which professionals should consider that maltreatment may have occurred or that a child is at high risk for abuse or neglect.

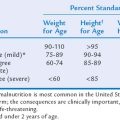

Neglect should be considered when a child is significantly underweight for age for no apparent reason or when this could be the result of inadequate intake, excessive output, or a combination of both; when a child does not have necessary medical or dental care or has an untreated illness or injury; when a child has chronic poor hygiene, such as lice, body odor, or scaly skin; when a child reports no caregiver or adult in the home; when a child lacks a safe, sanitary shelter or appropriate clothing for the weather; or when a child is abandoned or left with inadequate supervision.

Psychological maltreatment should be considered when a child is rejected (there is no affection or acknowledgement of the child as a person), terrorized (the child is threatened with injury and/or lives in a climate of unpredictability), ignored (the parent or caretaker is psychologically unavailable), isolated (the child is prevented from having social relationships), or corrupted (the child is encouraged to engage in antisocial behavior).5 These conditions can lead to the child’s failure to thrive, being depressed and anxious, and not being responsive to his or her environment. These situations should be considered “red flags” for possible maltreatment, but, as mentioned earlier, some may also be children’s responses to other stressful situations in their lives.

The methods and standards by which data are collected vary considerably. In 1993, the National Research Council reviewed the data-gathering process and made recommendations to improve the methods and reduce the disparity in the reports from the states. However, few changes have been made at the state or national levels to standardize the data-gathering process. Reporting or referral biases may skew the rate statistics of maltreatment in certain ethnic and socioeconomic groups. For example, African-American children6 and children living in poverty7 are more often reported and found to be maltreated than are children from other ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

Taking these caveats into consideration, we note that in 2003, about 3,353,000 reports of suspected child maltreatment were filed. About 31.7w% of these reports, involving 906,000 children, were substantiated. The rate of victimization in 2003 was 12.4 per 1000 children; 61.9% of these children were neglected, 18.9% were physically abused, 9.9% were sexually abused, 2.3 % were medically neglected, and 16.9% met the “other” category, including abandonment, threats (psychological abuse), and congenital drug addiction. (These percentages add up to more than 100% because children who were victims of more than one kind of abuse were counted in each category.) Of the maltreated children, 48.3% were boys and 51.7% were girls. In addition, the rate of abuse by age was as follows: For every 1000 children aged 0 to 3 years, 16.4 were abused; for every 1000 aged 4 to 7 years, 13.8; and of children younger than 1 year, 9.8%. With regard to the variable of race, 53.6% of maltreated children were white, 25.5% were African-American, 11.5% were Hispanic, 1.7% were Native American or Alaskan, 0.6% were Asian, and 0.2% were Pacific Islanders. With regard to perpetrators, 83.8% of children were abused by either or both parents; 13.4%, by nonparental adults; and 2.8%, by unknown perpetrators. Finally, approximately 1500 children died in 2003 as a result of their maltreatment, of whom 78.7% were younger than 4 years.8

Children with disabilities are much more vulnerable to maltreatment.9 In 2003, 6.5% of victims of maltreatment from the 34 states that reported this category had a disability, such as mental retardation, emotional disturbances, behavioral problems, physical disability, visual disturbances, and learning disabilities. Other studies suggest that children with disabilities are at least one to two times more likely to be abused than are typically developing children.10 Goldson,11 in a review of the literature on children with special health care needs, concluded that such children were at least three to four times more likely to be maltreated than were typically developing children.12,13,14

REPORTING, CLINICAL ASSESSMENT, AND TREATMENT OF THE MALTREATED CHILD

If a physician is the first professional to see a child and suspects maltreatment or is the person to whom a parent reports suspicions of abuse, he or she should document the history and perform a physical examination of the child. In addition, he or she must make a report to the appropriate state social services agency and/or the police. The investigation and substantiation of suspicions of abuse or neglect are the responsibility of the state or tribal child protection system or law enforcement, rather than the reporting individual. These agencies employ professionals who are trained to conduct investigations and are responsible for determining whether a child should be removed from the caregiver’s custody. In many clinical programs, social workers are trained to conduct forensic interviews with suspected victims and to work closely with the child protection system and law enforcement during the investigation. Many larger communities have specialized children’s advocacy centers with trained personnel to interview the child. Whenever child maltreatment is suspected, the physician must record accurate, complete documentation of the suspicion or allegations; how the suspicion of maltreatment occurred, such as an injury to the child or the child’s statements; and the results of the examination and subsequent actions, such as contact with the child protection system, law enforcement, or other professionals. Careful documentation is important when a report of suspected abuse is made, during the investigation, and in any future legal or court involvement. Finally, physicians must avoid influencing the content of the child’s report, being sure that the child speaks for himself or herself, both to maintain the child’s credibility and also to best protect the child.

The approach to the clinical assessment and treatment should follow a developmental psychopathology model,15 wherein the child’s developmental functioning and abilities are taken into consideration. The goal of the clinical assessment is to determine the child and caregivers’ overall functioning, adaptation, and level of symptoms. A thorough assessment of the family’s strengths and problems should be conducted, including the types of problems that need to be addressed at the parental, child, family, and social systems levels.16 The assessment may include interviews; paper-and-pencil measures; or structured observations with the child, siblings, and caregivers. In addition to the use of standard measures to assess cognitive functioning and general behavior, several specific measures have been developed and standardized to evaluate the child’s symptoms associated with the abuse. These measures include general assessments of trauma symptoms, such as the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children,17 and a measurement of sexual behavior problems, such as the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory.18 To assess psychological maltreatment, the Psychological Maltreatment Rating Scale19 provides an observational structure for evaluating mother-child interactions. Bonner and colleagues20 provided a complete review of assessment.

Evaluations of various treatment approaches for abused children and adolescents are increasing. Treatment interventions for abused children are conducted in therapeutic nurseries, day treatment programs, psychiatric or residential settings, and outpatient clinics. Clinicians must rely on techniques and approaches that are appropriate for the child’s cognitive and developmental level of functioning and are effective in reducing the child’s targeted symptoms. Reviews of the current treatment outcome literature indicate that abuse-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy is effective in reducing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).21 The treatment components include anxiety management techniques, exposure, education, and cognitive therapy. Treatment for families in which physical abuse has occurred has typically focused on the abusive parents and, more recently, has addressed the symptoms in the child victims.22–24 For some forms of neglect, research has yielded promising results for interventions that include home visitation as a primary approach.25–27

NEUROLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF NONACCIDENTAL TRAUMA

Although the focus of this chapter is on the cognitive and affective consequences of maltreatment, some of the physical consequences, particularly of injury to the central nervous system, are also considered. Ewing-Cobbs and associates28 characterized the neuroimaging, physical, neurobehavioral, and developmental findings in 20 children aged 0 to 6 years old who had experienced traumatic brain injury (TBI) as a result of inflicted or nonaccidental trauma (NAT) and compared them with 20 children with accidental TBI 1.3 months after the injury. They found that in 45% of the children with NAT, there were signs of preexisting injuries, such as cerebral atrophy, subdural hygromas, and ventriculomegaly. There were no such findings among the children with accidental injuries. In addition, subdural hematomas and seizures were more common among the children with NAT, and none of the children with accidental injuries had retinal hemorrhages. Glasgow Coma Scale scores in the children with NAT were suggestive of a worse prognosis, and of these children, 45% had mental retardation, in comparison with 5% of the children with accidental TBI.

In a later paper, Ewing-Cobbs and associates29 evaluated 28 children between the ages of 20 and 42 months, 1 and 3 months after their inflicted TBI, using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development–Second Edition. In comparing these children with those who had suffered accidental TBI, they found that the children with NAT had deficits in cognitive and motor functioning and that more than 50% showed persisting deficits in attention/arousal, emotional regulation, and motor coordination. As would be expected, the more severe the injury, as reflected in the lower Glasgow Coma Scale scores, the longer was the period of unconsciousness, and in the presence of cerebral edema and cerebral infarctions, the outcome was poorer. Perez-Arjona and coworkers,30 in a review of the literature, found that children with cerebral NAT had worse clinical outcomes than did those with accidental TBI. The abused children were cognitively impaired and had more severe neurological consequences. Late findings on computed tomographic scans and magnetic resonance images provided evidence of cerebral atrophy in 100% and cerebral ischemia in 50% of the NAT group. Thus, the conclusions that can be drawn from these studies are that inflicted injuries to the central nervous system are significantly more harmful than accidental injuries and that the outcome for children sustaining NAT is quite poor.

EFFECTS OF CHILD MALTREATMENT

An issue of importance to developmental-behavioral pediatricians is the effect of child maltreatment on children with disabilities.11 There has been a significant lack of research on the maltreatment of children with disabilities, and few state child welfare agencies document the presence or type of disability status of children entering the child protection system.31 This issue was addressed by Sullivan and Knutson,32 who studied a school-based population of more than 50,000 children to assess the prevalence of maltreatment among children identified with an existing disability; they related the type of disability to the type of abuse, and determined the effects of maltreatment on academic achievement and attendance rates for children with and without disabilities. They found a 31% prevalence rate of maltreatment of children with existing disabilities and a 9% rate among children without disabilities, which indicates that children with disabilities are 3.4 times more likely to be maltreated than are children who are not disabled. These authors further documented a significant relationship between maltreatment and disability that affected the child’s school performance.

Three factors appear to contribute to the heightened effect of abuse on children with disabilities: (1) their state of dependency; (2) being in institutional care; and (3) communication problems.33 Research has shown that physical disabilities that reduce a child’s credibility, such as mental retardation, deafness, or blindness, increase children’s risk for abuse,34 which emphasizes the necessity of increased protective measures for such children.

Physical Abuse

Children who are physically abused experience different kinds of injuries, ranging from bruises to skull and other fractures and to death. Studies suggest that the severity of a child’s physical injuries is related to young age,35 and according to national statistics, child fatalities caused by maltreatment are substantially higher in infants and children younger than 4 years.36 Earlier researchers explored the relationship between a child’s early medical and health status and subsequent abuse. Their findings suggested that factors such as a physical disability, low IQ, or birth complications might increase a child’s risk37; however, researchers did not find the factors to significantly increase a child’s risk beyond parental characteristics.38 Other studies have suggested that neonatal problems and failure to thrive were present in children who experienced physical abuse.39

Children’s responses to physical abuse are related to their age, developmental status, the severity and duration of the abuse, and the physical and psychological effects on the child. Their responses range from becoming passive and withdrawn to having high levels of hostility and aggressive behavior. An extensive body of research documents the heightened levels of aggression and related externalizing behavior in physically abused children.16 These problems include poor anger management40; increased rule violations, oppositional behavior, and delinquency41; drinking, smoking cigarettes, and drug use42; and property offenses and criminal arrests.43 Other studies have reported a relationship between physical abuse and borderline personality disorder,44 attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,39 and high rates of depression and conduct disorders in adolescents.45 Children who have been physically abused have also been found to have internalizing problems, such as depression and hopelessness46; Famularo and colleagues found that 30% of children and youth met criteria for PTSD, and 33% of the children with these criteria retained the full diagnosis 2 years later.47,48

Additional research has documented pervasive problems for victims of physical abuse in the areas of attachment, social competence, and interpersonal relationships. Studies report these children to have insecure attachments,49 separation problems,50 and difficulty making friends.43 A control group study of adolescents revealed that a history of physical abuse was associated with greater deficits in social competence and increased coercive behavior in dating relationships.51

It is clear that physical abuse can result in long-term psychosocial problems in living skills and relationships. Well-designed, longitudinal studies have revealed that children with a history of physical abuse are at twice the risk of the general population for being arrested for a violent crime52 and that they experience significant problems in adolescence and early adulthood, including suicidal ideation and attempts, depression, anxiety, and behavioral problems.53,54

Neglect

There are several forms of neglect that have varying effects on infants and children. These include (1) nutritional neglect (a lack of adequate food and nourishment); (2) educational neglect (failure to support attendance, achievement, and school activities, or allowing or encouraging truancy); (3) supervisory/protection neglect (leaving children unattended, not providing adequate supervision, or failing to protect children from maltreatment or dangerous situations); (4) physical/environmental neglect (failure to provide adequate, safe housing or appropriate clothing); (5) emotional neglect (failure to meet a child’s needs for nurturance and interaction); and (6) neglect of medical or mental health conditions (failure to adhere to medical or therapeutic procedures recommended for serious diseases, injuries, or emotional and behavioral problems).55

In many cases, infants and children suffer from several forms of neglect that can have serious consequences on the child’s development and behavior. Although physical and sexual abuses currently receive more public and professional attention, the majority of substantiated cases of maltreatment in the United States involve some form of neglect.36

Neglect can be chronic, such as long-standing lack of adequate nutrition, or a single episode, such as leaving children unattended for a period of time. For example, data demonstrate that children are most likely to die in fires when the fires are set by a child when appropriate adult supervision is lacking.56 Other forms of fatal neglect occur when caregivers fail to provide necessary medical care57 or fail to meet the nutritional and emotional needs of the child, which results in failure to thrive.58

The focus in research on neglected children has been mainly on physical and emotional neglect. In one of the first investigations to specifically study neglected children, Steele found learning problems, low self-esteem, and, as children grew older, a high rate of delinquency.59 Subsequent research has revealed that neglected children are less interactive with their peers,60 passive, tend toward helplessness in stressful situations, and display significant developmental delays.49 They also have severe language delays and disorders61 and experience a significant decline in school performance upon entering junior high school.62 Longitudinal studies have shown the negative effects of physical neglect, particularly during preschool and primary grades, on the children’s school behavior.55 These problems continue into adolescence; these youth have low school achievement scores, heavy alcohol use, and school expulsions and dropouts. Clearly, physical neglect can have devastating effects on children’s and adolescents’ functioning and adjustment.

Since the 1990s, studies have focused on the neurobiological consequences of maltreatment, and results suggest that maltreatment leads to compromised central nervous system and brain development.63 Studies have documented impairments in physiological functioning64 and smaller intracranial and cerebral volumes in maltreated children with PTSD than in controls.65,66 Perry67 discussed the severe, long-term consequences for brain function if a child’s needs for stable emotional attachments, physical touch from primary adult caregivers, and interactions with peers are not met. He suggested that if the necessary neuronal connections are lacking, the brain development for both caring behavior and cognitive capacities is damaged in a “lasting fashion.”

Current research findings clearly demonstrate that neglect is a major social problem affecting thousands of children across the United States. The neglected children who survive have problems developing adequate confidence, concentration, and the social skills necessary to adapt successfully to school and interpersonal relationships.55 In the absence of appropriate intervention in the family and for the child, the prognosis for these children is guarded.

Sexual Abuse

The short- and long-term effects of sexual abuse have the broadest research base of the four types of abuse. Since the 1980s, research findings have indicated that a variety of interpersonal and psychological problems are found more frequently in children with a history of sexual abuse than in nonabused children.68 Although many of these studies were retrospective and involved clinical samples, a well-designed, prospective, longitudinal study of the general population revealed that sexual abuse was associated with subsequent depression and posttraumatic stress.69 In evaluating the research in this area, investigators and clinicians agree that children who are sexually abused are at significant risk for problems in both the short term70 and the long term.33,71

In reviews of the specific effects associated with sexual abuse, it has been noted that as a group, these children do not consistently report significant levels of emotional distress.72 However, for many children, the experience can be frightening, confusing, and painful and can have significant negative effects on a child’s developmental progress. Studies have revealed that sexually abused children have more symptoms of depression and anxiety and lower self-esteem than do nonabused peers.73–75 Other research reports posttraumatic stress symptoms, including high levels of avoidance and reexperiencing of the event.73 Several studies documented that more than one third of the abused children met criteria for PTSD.76,77 Other documented symptoms include impaired cognitive functioning,78 problems in social competency,74,75 behavior problems,79 and increased sexual behavior.80

Although most research has focused on the effects on younger children, several investigators have assessed the effects on adolescents. They have identified major problems in this age group, including substance abuse,81 running away from home, bulimia,82 having trouble with teachers,83 and early pregnancy.84 A 10-year review of the literature33 revealed that a variety of psychiatric conditions—including major depression, somatization, substance abuse, borderline personality, PTSD, bulimia, and dissociative identity disorder—are later consequences of child sexual abuse. This comprehensive review identified three major problematic areas: psychiatric disorders; dysfunctional behaviors, particularly sexualized behaviors; and neurobiological dysregulation, including negative effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the sympathetic nervous system, and, possibly, the immune system.

For some childhood victims, these symptoms continue into adulthood. Studies have revealed increased arrest rates for sex crimes and prostitution,85 drug or alcohol dependence, and bulimia.86–88 Another study documented increased rates of major depression, attempted suicide, conduct disorder, social anxiety, drug and nicotine dependence, rape after age 18, and divorce.89 A meta-analysis of 37 studies revealed significant effects of child sexual abuse on later suicide, sexual promiscuity, and depression,90 documenting a causal relationship between the later development of psychopathology and a history of child sexual abuse.86

Psychological Maltreatment

Because children are often victims of multiple forms of abuse, the effects of psychological maltreatment are often difficult to distinguish from other types of maltreatment. Many professionals consider psychological maltreatment to be a core component of all forms of child abuse and neglect.91–94 Findings from longitudinal, cross-cultural, and comparison studies support this concept and document severe outcomes from chronic child neglect.

The Minnesota Parent-Child Project monitored a cohort of children from birth to adulthood whose mothers were at risk for parenting problems.95–97 In comparison with children from the control group, the maltreated children exhibited serious consequences. Children whose mothers were hostile or verbally abusive demonstrated anxious attachments, lack of impulse control, distractibility, hyperactivity, angry and noncompliant behavior, difficulty in learning and problem solving, negative emotions, and lack of persistence and enthusiasm. Researchers noted the most devastating effects occurred when a mother was psychologically unavailable (i.e., denied emotional responsiveness to the child). The outcomes for such children included poor progress in competency from infancy through the preschool years, anxious-avoidant attachment, noncompliance, lack of impulse control, low self-esteem, high dependence, self-abusive behavior, and serious psychopathology. Other longitudinal studies have shown that parental rejection and lack of positive parent-child interactions are significant predictors of childhood aggression and delinquency.98,99

Psychological maltreatment includes both acts of commission (e.g., parental hostility and verbal aggression) and acts of omission (e.g., parental neglect and indifference or denial of emotional responsiveness). Anthropological studies have demonstrated that parental rejection has negative effects on children in many of the world’s cultures.100 Rejected children tend to be aggressive, to have poor self-esteem, to be emotionally unstable and unresponsive, and to have a negative world view.

Other researchers have compared the differential effects of psychological maltreatment with other forms of abuse. Claussen and Crittenden92 found that psychological maltreatment was more accurately predictive of problematic developmental outcomes than was the severity of children’s physical injury, which emphasizes the need for intervention in the psychological aspects of the child’s environment. In comparing the effects of psychological maltreatment with those of physical and sexual abuse, investigators have found strong associations between psychological maltreatment and bulimia,101 depression, and low self-esteem.102,103 Although psychological harm is more difficult to observe and clearly document, research has established that it is a recognizable and serious condition that warrants increased attention to legal and child welfare policies and programs in order to intervene more effectively on behalf of children.104

EFFECTS ON ADULTS

Both retrospective and prospective studies have clearly documented long-term negative effects of childhood abuse or neglect on adults. These effects include poor psychosocial adjustment; delinquent and criminal behavior; engaging in frequent, indiscriminate sexual behavior and sexual assault; increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection, repeated victimization, depression and substance abuse, and intellectual and academic problems.105–109 Researchers documented in adults the health-related consequences of maltreatment in childhood.110 The authors found that the more severe the abuse during childhood was, the greater was the likelihood that victims would later smoke, be alcoholic, have chronic depression, have numerous sexual partners, and be involved in domestic violence, rape, and suicide.

In a retrospective study, McCord111 studied 232 men identified in social service case records opened between 1939 and 1945. In 1957, these records were coded, and the parents in these families were divided into four groups: (1) rejecting parents, (2) neglectful parents, (3) abusive parents, and (4) loving parents. McCord found an increase in juvenile delinquency during adolescence in the maltreated children. Of the maltreated boys, 45% had an increased incidence of criminal records, alcoholism, mental illness, problems with control of aggression, and early death. Of men rejected by their parents, 53% were convicted of crimes, as opposed to 35% who were neglected or 39% who were physically abused. Only 23% of the men from loving families were convicted of crimes. Fifty-five percent of maltreated individuals appeared to reach adulthood without significant social difficulties. The researches associated this positive outcome with a strong mother who was both educated and self-confident. Widom112 also identified an increased incidence of criminal records, alcoholism, mental illness, problems with control of aggression, and early death, although an absence of crimes against children was also noted. Both studies raise the question of protective factors and interventions that might mitigate or ameliorate the later consequences of child maltreatment and enhance positive outcomes.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

Child maltreatment is a complex social, psychological, political, and cultural phenomenon. Knowledge of risk factors should enable clinicians to prevent, or at least diminish, its prevalence. Children living in poverty, those with atypical and disruptive behaviors, and those with disabilities are known to be at much higher risk for maltreatment.11

For example, Sobsey113 and Verdugo and associates114 invoked an ecological approach that involves changing attitudes that allow maltreatment of children with disabilities. The first task is to alter the way society views children with disabilities, leading to more positive perceptions of such children and a subsequent decrease in their risk of maltreatment. These authors suggested that relationships be established between families with children with special health needs and those with typical children, in an environment that positively acknowledges and celebrates the uniqueness of the disabled child and promotes education about children with special needs. Such settings may include daycare centers, schools, and hospitals. Because the most frequent perpetrators of abuse are family members, these authors also emphasize the need to support the children’s caregivers.

Numerous professional organizations provide valuable information and support regarding child abuse and neglect for clinicians and institutions. Examples include the American Academy of Pediatrics (see www.aap.org for additional information), the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI),63 the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (www.apsac.org), and the International Society on the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (www.ISPCAN.org).

1 Federal Child Abuse Prevention Treatment Act, 42 USC §5106g(4), 1974.

2 Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, et al. The battered child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181:17-24.

3 Helfer RE. The epidemiology of child abuse and neglect. Pediatr Ann. 1984;13:745-751.

4 Kleinman PK. Diagnostic Imaging of Child Abuse, 2nd ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1998.

5 Garbarino J, Guttman E, Seeley JW. The Psychologically Battered Child. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1986.

6 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2001: Reports from the States to the National Child Abuse and Neglect System. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002.

7 ISCHHS, Children’s Bureau, 2000.

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2003: Reports from the States to the National Child Abuse and Neglect System. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005.

9 McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:137-140.

10 Westat, Inc. A Report on the Maltreatment of Children with Disabilities. Washington, DC: National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, 1993.

11 Goldson E. Maltreatment among children with disabilities. Infants Young Child. 2001;13:44-54.

12 Ten Bensel RW, Rheinberger MM, Radbill SX. Children in a world of violence: The roots of child maltreatment. In: Helfer ME, Kempe RS, Krugman RD, editors. The Battered Child. 5th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997:3-18.

13 Zigler E, Hall NW. Physical child abuse in America: Past, present and, future. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child Maltreatment: Theory and Research on the Causes and Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989:38.

14 Myers JEB. A History of Child Protection in America. Philadelphia: Xlibris, 2004.

15 Friedrich WN. An integrated model of psychotherapy for abused children. In: Myers JEB, Berliner J, Briere J, et al, editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002:141-158.

16 Kolko DJ. Child physical abuse. In: Myers JEB, Berliner J, Briere J, et al, editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002:21-54.

17 Briere J. Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1996.

18 Friedrich WN: Child Sexual Behavior Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1997.

19 Brassard MR, Hart SN, Hardy DB. The Psychological Maltreatment Rating Scale. Child Abuse Negl. 1993;17:715-729.

20 Bonner BL, Logue MS, Kaufman KL, et al. Child maltreatment. In: Walker CE, Roberts MC, editors. Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 2001:989-1030.

21 Cohen JA, Berliner L, Mannarino AP. Treating traumatized children: A research review and synthesis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2000;1:29-46.

22 Azar ST, Wolfe DA. Child physical abuse and neglect. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of Childhood Disorders. New York: Guilford; 1998:501-544.

23 Oats RK, Bross DC. What have we learned about treating physical abuse: A literature review of the last decade. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:463-473.

24 Wolfe D. Child Abuse: Implications for Child Development and Psychopathology, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999.

25 Lutzker JR. Behavioral treatment of child neglect. Behav Modif. 1990;14:301-315.

26 Lutzker JR, Bigelow KM, Doctor RM, et al. An eco-behavioral model for the prevention and treatment of child abuse and neglect. In: Lutzker JR, editor. Handbook for Child Abuse Research and Treatment. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:239-266.

27 Olds DJ, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. JAMA. 1997;278:637-643.

28 Ewing-Cobbs L, Kramer L, Prasad M, et al. Neuroimaging, physical and developmental findings after inflicted and noninflected traumatic brain injury in young children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:300-307.

29 Ewing-Cobbs L, Prasad M, Kramer L, et al. Inflicted traumatic brain injury: Relationship of developmental outcome to severity of injury. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31:251-258.

30 Peerez-Arjona E, Dujovny M, Del Proposto Z, et al. Late outcome following central nervous system injury in child abuse. Child Nerv Syst. 2003;19:69-81.

31 Bonner BL, Crow SM, Hensley LD. State efforts to identify maltreated children with disabilities: A follow-up study. Child Maltreatment. 1997;2:56-60.

32 Sullivan PM, Knutson JF. Maltreatment and disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Neglect. 2000;24:1257-1273.

33 Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269-278.

34 Westcott H, Jones D. Annotation: The abuse of disabled children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:497-506.

35 Lung CT, Daro D. Current Trends in Child Abuse Reporting and Fatalities: The Results of the 1995 Annual Fifty State Survey. Chicago: National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse, 1996.

36 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005.

37 Belsky J, Vondra J. Lessons from child abuse: The determinants of parenting. In: Carlson CD, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and Research on the Causes and Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989:153-202.

38 Ammerman RT. The role of the child in physical abuse: A reappraisal. Violence Victims. 1991;6(2):87-101.

39 Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff RT. Medical and developmental histories of maltreated children. Clin Pediatr. 1992;31:536-541.

40 Beeghly M, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment, attachment, and the self system: Emergence of an internal state lexicon in toddlers at high social risk. Dev Psychopathol. 1994;6:5-30.

41 Walker E, Downey G, Bergman A. The effects of parental psychopathology and maltreatment on child behavior: A test of the diathesis-stress model. Child Dev. 1989;60:15-24.

42 Kaplan S, Pelcovitz D, Salzinger S, et al. Adolescent physical abuse: Risk for adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:954-959.

43 Gelles RJ, Straus MA. The medical and psychological costs of family violence. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990:425-430.

44 Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Posttraumatic stress disorder among children clinically diagnosed as borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:428-431.

45 Pelcovitz D, Kaplan S, Goldenberg B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in physically abused adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:305-312.

46 Allen DM, Tarnowski KG. Depressive characteristics of physically abused children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1989;17:1-11.

47 Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff R, et al. Maternal and child posttraumatic stress disorder in cases of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:27-36.

48 Famularo R, Fenton T, Augustyn M, et al. Persistence of pediatric post traumatic stress disorder after 2 years. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:1245-1248.

49 Crittenden PM, Ainsworth MDS. Child maltreatment and attachment theory. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child Maltreatment: Theory and Research on the Causes and Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989:432-463.

50 Lynch M, Cicchetti D. Patterns of relatedness in maltreated and non-maltreated children: Connections among multiple representational models. Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:207-226.

51 Wolfe D, Werkele C, Reitzel-Jaffe D, et al. Factors associated with abusive relationships among maltreated and non-maltreated youth. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:61-85.

52 Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;106:3-28.

53 Silverman AB, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. The long-term sequelae of child and adolescent abuse: A longitudinal community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;8:709-723.

54 Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, et al. Childhood abuse and neglect: Specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1490-1505.

55 Erickson MF, Egeland B. Child neglect. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al, editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002:3-20.

56 Bonner BL, Crow SM, Logue MB. Fatal child neglect. In: Dubowitz H, editor. Neglected Children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:156-173.

57 Geffken G, Johnson SB, Silverstein J, et al. The death of a child with diabetes from neglect: A case study. Clin Pediatr. 1992;31:325-330.

58 Oates RK, Kempe RS. Growth failure in infants. In: Helfer ME, Kempe RS, Krugman RD, editors. The Battered Child. 5th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997:374-391.

59 Steele BF: Psychological Dimensions of Child Abuse. Presented at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Denver, February 1977.

60 Hoffman-Plotkin D, Twentyman CT. A multimodal assessment of behavioral and cognitive deficits in abused and neglected preschoolers. Child Dev. 1984;35:794-802.

61 Katz K. Communication problems in maltreated children: A tutorial. J Child Commun Dis. 1992;14:147-163.

62 Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finklehor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:164-180.

63 Perry BD. Incubated in terror: Neurodevelopmental factors in the “cycle of violence.”. In: Osofsky JD, editor. Children in a Violent Society. New York: Guilford; 1997:124-149.

64 Lewis DO. From abuse to violence: Psychophysiological consequences of maltreatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:383-391.

65 DeBellis MD, Baum AS, Birmaher B, et al. Developmental traumatology part I: Biological stress systems. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1259-1270.

66 DeBellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, et al. Developmental traumatology part II: Brain development. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1271-1284.

67 Perry BD. Childhood experience and the expression of genetic potential: What childhood neglect tells us about nature and nurture. Brain Mind. 2002;3:79-100.

68 Wolfe VV, Birt J. The psychological sequelae of child sexual abuse. Adv Clin Child Psychol. 1995;17:233-263.

69 Boney-McCoy S, Finklehor D. Psychosocial sequelae of violent victimization in a national youth sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:726-736.

70 Kendall-Tackett KA, Eckenrode J. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: A developmental perspective. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:161-169.

71 Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynseky MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;34:1365-1374.

72 Berliner L, Elliott DM. Sexual abuse of children. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al, editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002:55-78.

73 McLeer SV, Dixon JF, Henry D, et al. Psychopathology in non-clinically referred sexually abused children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1326-1333.

74 Mannarino AP, Cohen JA. Abuse-related attributions and perceptions, general attributions, and locus of control in sexually abused girls. J Interpers Violence. 1996;11:162-180.

75 Mannarino AP, Cohen JA. A follow-up study of factors that mediate the development of psychological symptomatology in sexually abused girls. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:246-260.

76 Dubner AE, Motta RW. Sexually and physically abused foster care children and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:367-373.

77 Ruggiero KJ, McLeer SV, Dixon JF. Sexual abuse characteristics associated with survivor psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:951-964.

78 Rust JO, Troupe PA. Relationships of treatment of child sexual abuse with school achievement and self-concept. J Early Adolesc. 1991;11:420-429.

79 Wind TW, Silvern LE. Type and extent of child abuse as predictors of adult functioning. J Fam Violence. 1992;7:261-281.

80 Friedrich WN, Dittner CA, Action R, et al. Child Sexual Behavior Inventory: Normative, psychiatric and sexual abuse comparisons. Child Maltreat. 2001;6:37-49.

81 Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno RE, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692-700.

82 Hibbard RA, Ingersoll GM, Orr DP. Behavior risk, emotional risk, and child abuse among adolescents in a non-clinical setting. Pediatrics. 1990;86:896-901.

83 Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1406-1416.

84 Herrenkohl E, Herrenkohl R, Egolf B, et al. The relationship between early maltreatment and teenage parenthood. J Adolesc. 1998;21:291-303.

85 Widom C, Ames M. Criminal consequences of childhood sexual victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:303-318.

86 Kendler K, Bulik C, Silber J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance abuse disorders in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953-959.

87 Schuck AM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and alcohol symptoms in females: Causal inferences and hypothesized mediators. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1069-1092.

88 Rich CL, Combs-Lane AM, Resnick HS, et al. Child sexual abuse and adult sexual revictimization. In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O’Leary A, et al, editors. From Child Sexual Abuse to Adult Sexual Risk: Trauma, Revictimization, and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:49-68.

89 Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: Results from a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:139-146.

90 Paolucci E, Genuis M, Violato C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. J Psychol. 2001;135(1):17-36.

91 Binggeli NJ, Hart SN, Brassard MR. Psychological Maltreatment: A Study Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001.

92 Claussen AH, Crittenden PM. Physical and psychological maltreatment: Relations among types of maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 1991;15:5-18.

93 Brassard MR, Germain R, Hart SN, editors. Psychological Maltreatment of Children and Youth. New York: Pergamon, 1987.

94 Garbarino J, Guttman E, Seeley J. The Psychologically Battered Child: Strategies for Identification, Assessment and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1986.

95 Egeland B. Mediators of the effects of child maltreatment on developmental adaptation in adolescence. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology, Volume VIII: The Effects of Trauma on the Developmental Process. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997:403-434.

96 Egeland B, Erickson M. Psychologically unavailable caregiving. In: Brassard MR, Germain R, Hart SN, editors. Psychological Maltreatment of Children and Youth. New York: Pergamon; 1987:110-120.

97 Erickson MF, Egeland B, Pianta R. The effects of maltreatment on the development of young children. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child Maltreatment: Theory and Research on the Causes and Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989:647-684.

98 Lefkowitz M, Eron L, Walder L, et al. Growing Up to Be Violent: A Longitudinal Study of the Development of Aggression. New York: Pergamon, 1977.

99 Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In: Tonry M, Morris N, editors. Crime and Justice, an Annual Review of the Research. 7th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986:29-149.

100 Rohner RP, Rohner EC. Antecedents and consequences of parental rejection: A theory of emotional abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1980;4:189-198.

101 Rorty M, Yager J, Rossotto E. Childhood sexual, physical, and psychological abuse in bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1122-1126.

102 Briere J, Runtz M. Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14:357-364.

103 Gross AB, Keller HR. Long-term consequences of childhood physical and psychological maltreatment. Aggress Behav. 1992;18:171-185.

104 Hart SN, Brassard MR, Binggeli NJ, et al. Psychological maltreatment. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al, editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002:79-103.

105 Koenig LJ, Clark H. Sexual abuse of girls and HIV infection among women: Are they related? In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O’Leary A, et al, editors. From Child Sexual Abuse to Adult Sexual Risk: Trauma, Revictimization, and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:69-92.

106 Perez CM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and long-term intellectual and academic outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:617-633.

107 Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269-278.

108 Rich CL, Combs-Lane AM, Resnick HS, et al. Child sexual abuse and adult sexual revictimization. In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O’Leary A, et al, editors. From Child Sexual Abuse to Adult Sexual Risk: Trauma, Revictimization, and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:49-68.

109 Schuck AM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and alcohol symptoms in females: Causal inferences and hypothesized mediators. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1069-1092.

110 Felitti VJ: The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Health Status: Turning Gold into Lead. Presented at the Snowbird Conference of the Child Trauma Network of the Intermountain West, Salt Lake City, UT, September 2003. (Available at: www.acestudy.org; accessed 1/29/07.)

111 McCord J. A forty year perspective on effects of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1983;7:265.

112 Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence and child abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:355-367.

113 Sobsey D. An integrated ecological model of abuse. In: Violence and Abuse in the Lives of People with Disabilities: The End of Silent Acceptance?. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1994:145-174.

114 Verdugo MA, Bermejo BG, Fuentes J. The maltreatment of intellectually handicapped children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:205-215.

115 Dawes CG: Defining the Children’s Hospital Role in Child Maltreatment. Alexandria, VA: National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions, 2005. (Available at: www.childrenshospitals.net; accessed 1/29/07.)