Chapter 120 Chiari Malformation, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Fibromyalgia

A Paradigm for Care

The Chiari malformation (CM) usually is a congenital hindbrain disorder that can be acquired in rare cases. In 1891 Hans Chiari, a pathologist, was the first to describe the deformity and group it into different categories based on the severity of tonsillar and cerebellar descent below the foramen magnum.1

The incidence of Chiari malformation in a study of 22,000 brain MRIs was reported to be 1 in 1280 individuals.2 This study probably underestimates the true incidence of Chiari malformation in asymptomatic individuals and in the general population. There is a higher preponderance of Chiari malformation I in females than in males, by a ratio of 3:2.2

There seems to be some evidence of genetic transmission in a subset of patients with Chiari malformation with syringomyelia.2–4 The extent of cerebellar herniation does not necessarily correlate with subjective complaints, physical findings, and neurologic findings.4

Syringomyelia occurs when cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) forms a cavity within the spinal cord. Chiari malformation is the leading cause of pathologic syrinx formation. It is thought that the displaced cerebellar tonsil acts as a plug that obstructs CSF flow and may act as a miniature piston (i.e., the “piston theory”) to drive CSF inside the spinal cord.5 A syrinx cavity also can develop in other cases of CSF flow obstruction, such as spinal cord tumors, infection, or trauma. The incidence of syringomyelia in Chiari malformation I is estimated to be 50% to 75%.6

What Is Fibromyalgia Syndrome or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?

Fibromyalgia syndrome is characterized by chronic widespread pain and multiple tender joints.7,8 Most patients have coexisting fatigue, sleep disturbance, paresthesias, and morning stiffness.8 More than 80% of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome have chronic fatigue syndrome. There are more clinical similarities than differences between the two entities. The patient is diagnosed with fibromyalgia syndrome if the predominant complaint is pain or chronic fatigue syndrome if the predominant complaint is fatigue. The prevalence of fibromyalgia is reported to be 2.1% to 5.7% in the general population and may be as high as 10% to 20% in some settings.9–11

In one study, fibromyalgia syndrome was found to be 13 times more common in patients following cervical spine injury as opposed to patients with lower extremity injury.12 It also is reported that 30% to 56% of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome have coexisting mental disorders, anxiety, or depression.13,14 Fibromyalgia can be diagnosed concomitantly in 34% of patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus), and in 28% of patients with chronic spinal pain syndromes.7

Fibromyalgia syndrome currently is thought to be a disorder of pain regulation or “central sensitization.”15 There seems to be significant overlap in symptoms of various chronic disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic migraines, chronic fatigue syndrome, and posttraumatic stress disorders. Patients with fibromyalgia have lower pain and heat thresholds and have higher catastrophizing and somatization behaviors in response to painful stimuli.16 Substance P, a peptide associated with chronic pain, is elevated in the CSF of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome.17 There seems to be a genetic predisposition as well: first-degree relatives of patients with fibromyalgia have higher rates of developing fibromyalgia syndrome. There is an increased co-aggregation of fibromyalgia syndrome with major mood disorders in families.18

Controversial Link between Fibromyalgia or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Chiari Malformation: Does It Really Exist?

In 1999, an article in The Wall Street Journal and an ABC 20/20 television program featuring prominent neurosurgeons suggested surgical management for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome with Chiari malformation or cervical stenosis.8

In 2001, in an abstract presented at the Congress of Neurological Surgeons in San Diego, Heffez reported on 64 patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome with signs and symptoms consistent with cervical myelopathy from either Chiari malformation or cervical stenosis who underwent surgery.19 There was no randomization in assigning patients. At 6 months, statistically significant improvement was reported as compared with a nonsurgical control group in terms of pain, grip strength, and balance impairment. Headache also improved in 90% of patients in the surgical group compared with 45% in the nonsurgical group. Non–statistically significant improvement also was seen in the surgical group in terms of fatigue, depression, insomnia, and paresthesias.

A link between fibromyalgia syndrome and Chiari malformation has been suggested, with the recommendation that patients with fibromyalgia should be aggressively worked up for possible neurologic disorders such as Chiari malformation or cervical stenosis.19,20 Based on the available literature, however, there is no evidence of a direct link between fibromyalgia syndrome/chronic fatigue with Chiari malformation with or without syringomyelia.21 It is plausible to suggest that patients who have long-standing neurologic disorders (e.g., cervical myelopathy, Chiari malformation, cervical stenosis) can develop secondary fibromyalgia. This is consistent with the concept of chronic central sensitization states. Compared with the prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome, which is 5% to 20% in the general population), the 0.77% incidence of radiographic Chiari malformation in 22,591 brain/cervical MRI scans reviewed is relatively small.2 It could be by chance alone that they are linked. The nonstatistical improvement in fibromyalgia somatic complaints in the operated group could be explained by reduction in stress and the feeling that something “substantial” had been done. It is unclear whether these somatic symptoms referred to fibromyalgia improved permanently or if there was symptom recurrence over time, because no long-term follow-up was done.

An MRI study of consecutive patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia syndrome at two tertiary centers showed no increase in the prevalence of Chiari malformation/cervical stenosis in this group over that of the “normal” control group. In fact, 11 of 15 patients (73%) in the control group, compared with 8 of 26 patients (31%) in the fibromyalgia group, showed evidence of some degree of tonsillar herniation.22

How Is Fibromyalgia Diagnosed?

Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology created simpler, clinically friendly criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia syndrome.23 These were designed not to replace the 1990 criteria but to provide clinically more relevant alternative criteria to diagnose fibromyalgia with similar diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. The most important change was to do away with tender point palpations and to include a widespread pain index score. The coexisting somatic symptoms that are so common in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome were highlighted.

Chiari Malformation and Syringomyelia: Clinical Diagnosis

Chiari malformation presents with symptoms related to brainstem compression, hydrocephalus, syringomyelia, or transient increase in intracranial pressure.1

The major presenting symptoms of Chiari malformation with syringomyelia are weakness (more pronounced in the upper extremity than in the lower extremity), pain (neck pain with extremity radiation), paresthesias or hyperesthesias, suboccipital headaches, and gait difficulties. 6,24–26

Intracranial pressure increase/fluctuation

Progressive syrinx enlargement causing central spinal cord dysfunction

In most cases of symptomatic Chiari malformation and syringomyelia, it took an average of 3 to 6 years from the start of symptoms to reach the diagnosis and begin definitive treatment.6,24,25

Significant overlap of somatic symptoms in fibromyalgia syndrome and Chiari malformation may be seen. Muscle pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive problems, headache, and dizziness are common in both. Chronic stress due to a significant delay in diagnosis, chronic disability, genetic susceptibility, and concomitant anxiety or depression has been suggested as a major contributing factor. Secondary gain issues in cases where trauma is involved (e.g., work injuries, motor vehicle accidents) may play a role.

The headache in Chiari malformation is specifically suboccipital/occipital, of variable duration, and aggravated by the Valsalva maneuver, cough, and change of body posture.27,30 The headache pattern in fibromyalgia syndrome is more generalized and unprovoked. Most of these headaches can be classified as migraine with or without aura, tension headache, or analgesic overuse headache.31

It has been suggested—although not clearly proven—that the extent of pain and mood disorders in Chiari malformation/cervical stenosis is higher than in chronic pain states that have no evidence of central nervous system disorder.32

Paradigm of Care in Chiari Malformation with Syringomyelia

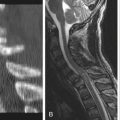

The most important imaging study for assessing the extent of anatomic tonsillar herniation and its pathophysiologic significance is a brain/spine MRI with cine CSF flow study. Obstruction of CSF flow at the craniovertebral junction and the absence of normal pulsatile flow with cine CSF MRI studies have an important physiologic significance in Chiari malformation and syringomyelia. This test is extremely sensitive in detecting abnormal tonsillar motion and the CSF flow via the foramen magnum and around the syrinx cavity.28 Chiari-type headache correlates with tonsillar motion and subsequent reduction in the arachnoid space at the foramen magnum.28 The results of cine phase contrast MRI are valuable in the presurgical assessment of “symptomatic” Chiari malformation. Normal studies are an independent risk factor for surgical failure, regardless of the degree of tonsillar herniation.29 Forty percent of patients with a normal cine CSF flow study had treatment failure following surgery, compared with only 5% where there was documented CSF flow obstruction.29

Patients usually can be placed into one of three different categories after thorough evaluation of different specialties and review of appropriate imaging studies4:

1. Patients who have clinical features of a Chiari malformation, as evidenced by findings consistent with disruption of central pathways involving cerebrospinal, cerebellospinal, or sensory spinothalamic pathways (evidence of “hard” neurologic findings). Abnormalities in cine phase MRI CSF flow studies showing partial or complete CSF flow obstruction are present. These patients will likely benefit with surgery.

2. Patients who have significant somatic symptoms with features consistent with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. They may have radiographic Chiari malformation, but they do not have objective neurologic findings and CSF flow studies are normal. These patients will not benefit with surgery.

3. A “mixed” pattern showing possible neurologic findings attributed to brainstem compression or cord dysfunction from a syrinx, but these are nonprogressive, mild, and “soft” findings at best. Cine CSF flow studies are normal. These patients also may present with features consistent with fibromyalgia, with significant somatic symptoms and psychosocial distress. This group is extremely challenging. These patients are managed conservatively, and very few will be considered for surgery. They are followed for evidence of neurologic deterioration. Aggressive management of coexisting fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue, chronic headaches, and depression/mood disorders is undertaken. Patients may benefit from admission to a multidisciplinary chronic pain rehabilitation program.

Levy W.J., Mason L., Hahn J.F. Chiari malformation presenting in adults: a surgical experience in 127 cases. Neurosurgery. 1983;12(4):377-390.

McGirt M.J., Nimjee S.M., Fuchs H.E. Relationship of cine phase contrast MRI with outcome after decompression for Chiari I malformations. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:140-146.

Oldfield E.H., Murazsko K., Shawker T.H., Parronas N.J. Pathophysiology of syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation of the cerebellar tonsils: implication for diagnosis and treatment. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:3-15.

Thieme K., Turk D., Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychological variables. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:837-844.

Wilke W. Can fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome be cured by surgery? Cleve Clin J Med. 2001;68(4):277-279.

Wolfe F., Clauw D., Goldenberg D., et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:600-610.

1. Steinmetz M., Benzel E. Surgical management of Chiari malformation. Neurosurg Q. 2003;13(2):105-112.

2. Meadows J., Kraut M., Guarnieri M., et al. Asymptomatic Chiari type I malformations identified on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:920-926.

3. Oldfield E.H., Murazsko K., Shawker T.H., Parronas N.J. Pathophysiology of syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation of the cerebellar tonsils: implication for diagnosis and treatment. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:3-15.

4. Benzel E. Management of Chiari malformation. Spineuniverse.com. 2009.

5. Levine D.N. The pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with lesions at the foramen magnum: a critical review of existing theories and proposal of a new hypothesis. J Neurosurg Sci. 2004;220:3-21.

6. Dyste G.N., Menezes A.H., VanGilder J.C. Symptomatic Chiari malformation. J Neurosurg. 1992;42:1519-1521.

7. Wolfe F., Smythe H.A., Yunus M.B., et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160-172.

8. Pamuk O.N., Yesil Y., Cakir N. Factors that affect the number of tender points in fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain patients who did not meet the ACR 1990 criteria for fibromyalgia: are tender points a reflection of neuropathic pain? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36:130-134.

9. Wolfe F., Cathey M.A. Prevalence of primary and secondary fibrositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:965-968.

10. Croft P., Rigby A.S., Boswell R. The prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:710-713.

11. Wolfe F., Ross K., Anderson J., et al. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):19-28.

12. Buskila D., Neumann L., Vaisberg G., et al. Increased rates of fibromyalgia following cervical spine injury. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(3):446-452.

13. Benjamin S., Morris S., McBeth J. The association between chronic widespread pain and mental disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(3):561-567.

14. Thieme K., Turk D., Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychological variables. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:837-844.

15. Yunus M. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:339-356.

16. Geisser M., Casey K., Brucksch C.B. Perception of noxious and innocuous heat stimulation among healthy women and women with fibromyalgia: association with mood, somatic focus, and catastrophizing. Pain. 2003;102:243-250.

17. Bradley L.A., Alarcon G.S. Is Chiari malformation associated with increased levels of substance P and clinical symptoms in persons with fibromyalgia? Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(12):2731-2736.

18. Arnold L.M., Hudson J.I., Hess E.V. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 50(3), 2004. 994–952

19. Heffez D.S., Ross R.E., Shade-Zeldow Y., et al. Clinical evidence for cervical myelopathy due to Chiari malformation and spinal stenosis in a non-randomized group of patients with the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:516-523.

20. Holman A.J. Positional cervical spinal cord compression and fibromyalgia: a novel comorbidity with important diagnostic and treatment implications. Pain. 2008;9(7):613-622.

21. Wilke W. Can fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome be cured by surgery. Cleve Clinic J Med. 2001;68(4):277-279.

22. Claw D.J., Bennett R.M., Rosner M.J. Prevalence of Chiari malformation and cervical stenosis in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(suppl):173A.

23. Wolfe F., Clauw D., Goldenberg D., et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:600-610.

24. Milhorat T.H., Trinidad E.M., Kula R.W. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(5):1005-1017.

25. Levy W.J., Mason L., Hahn J.F. Chiari malformation presenting in adults: a surgical experience in 127 cases. Neurosurgery. 1983;12(4):377-390.

26. Aghakhani N., Parker F., David P. Long-term follow up of Chiari related syringomyelia in adults: analysis of 157 surgically treated cases. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:308-315.

27. Sansur C.A., Heiss J.D., Devroom H.L., et al. Pathophysiology of headache associated with cough in patients with Chiari I malformation. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:453-458.

28. Pujol J., Roig C., Capdevila A., et al. Motion of the cerebellar tonsils in Chiari type 1 malformation studies by cine phase contrast MRI. Neurology. 1995;45:1746-1753.

29. McGirt M.J., Nimjee S.M., Fuchs H.E., George T.M. Relationship of cine phase contrast MRI with outcome after decompression for Chiari I malformations. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:140-146.

30. Pascual J., Oterino A., Berciano J. Headache in type I Chiari malformation. Neurology. 1992;42:1519-1521.

31. Marcus D.A., Bernstein C., Rudy T. Fibromyalgia and headache: an epidemiologic study supporting migraine as part of FMS. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24(6):595-601.

32. Thimineur M., Kitaj M., Kravitz E., et al. Functional abnormalities of the cervical cord and lower medulla and their effect on pain: observations in chronic pain patients with incidental mild Chiari malformation and moderate to severe cervical cord compression. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:171-179.