54 Chest Pain

• Observation and repeated testing are extremely valuable in a patient with chest pain in whom the diagnosis is unclear.

• Rapid ruling out of acute myocardial infarction can be performed with serial cardiac marker testing once an appropriate interval after symptom onset has elapsed (8 hours for troponin I or T), although shorter intervals may be acceptable if immediate stress testing is performed.

• Normal cardiac marker values do not exclude unstable angina.

• Consider life-threatening diagnoses other than acute myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain, including aortic dissection, which is frequently missed and often manifested atypically.

Epidemiology

Every year 6.2 million people are seen in U.S. emergency departments (EDs) with complaints of chest pain, which accounts for roughly 6% of ED visits and is the second most common reason for such visits. The differential diagnosis of chest pain ranges from benign causes, such as muscle strain, to the immediately life-threatening ones, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, and aortic dissection. Although the focus in patients with chest pain remains appropriately on life-threatening causes, a majority of patients have benign or indeterminate diagnoses after ED evaluation. In one study of ED patients with symptoms consistent with acute cardiac ischemia, only 8% had acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 9% had unstable angina.1 Another investigation of patients evaluated in the ED for nontraumatic chest pain found that AMI was diagnosed in 4%, unstable angina or stable coronary disease in 7.5%, and pulmonary embolism or aortic dissection in less than 1%.2 Given the potentially lethal nature of conditions manifested as chest pain and the lack of sensitivity or specificity, in many instances, of the history and physical examination, the emergency physician (EP) must have an organized approach, a complete differential diagnosis, and a thorough understanding of assessment and management of this common complaint.

Pathophysiology

Visceral pain, from internal structures such as the heart, lungs, esophagus, and aorta, may be difficult for the patient to define or localize. It is experienced as discomfort or a vague sensation and is often difficult to pinpoint.

Somatic pain, from chest wall structures and the parietal pleura, is often easier to describe and localize. Somatic pain may be sharp or stabbing and exacerbated by movement or position.

Referred pain, from irritation or inflammation of the upper abdominal contents, is a form of visceral pain that may be perceived in the chest wall, shoulder, or upper part of the back.

A differential diagnosis based on anatomic structures within the chest is presented in Box 54.1.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Most patients with nontraumatic chest pain warrant high triage priority and an early electrocardiogram (ECG) (recommended within 10 minutes) to evaluate for AMI. Patient stabilization, evaluation of the history, physical examination, and diagnostic and therapeutic interventions proceed simultaneously. As assessment continues, interventions are refined (Box 54.2). Importantly, the history and physical findings alone are often inadequate to definitively establish or exclude life-threatening diagnoses.

Box 54.2 Approach to Patients with Chest Pain

• Use the term discomfort as opposed to pain to facilitate communication.

• Do not ascribe partially reproducible pain to a musculoskeletal cause. Pain arising from inflammation of the pericardium (secondary to AMI or pericarditis) or inflammation of the pleura (pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, or pleurisy) can be partially reproduced by palpation.

• Chest pain that is completely pleuritic (present only on inspiration) or completely reproducible significantly decreases suspicion for cardiac causes and raises suspicion for pulmonary or musculoskeletal causes. Partially pleuritic (worse with inspiration) or partially reproducible chest pain has much less predictive value.

• Substantial evidence suggests that responses to treatments such as sublingual nitroglycerin or a “gastrointestinal cocktail” do not differentiate the etiology of the chest pain.

• Do not overestimate the value of low-risk features when high-risk features are present (i.e., pain that is completely pleuritic but radiates to the left arm should still raise concern for possible acute coronary syndrome).

• The history and physical examination of patients with nonspecific chest pain are inadequate to justify discharge without further evaluation.

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Epidemiology

Several risk stratification systems have been proposed for acute coronary syndrome. These systems have been shown to help in risk stratification, thereby enabling triage decisions. They have never been shown to improve the ability to formulate discharge decisions in comparison with practitioner judgment. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have published criteria to determine a patient’s risk for coronary artery disease and adverse outcomes from acute coronary syndrome.3 These guidelines are cumbersome and more appropriately applied to patients with documented disease than to undifferentiated ED patients. A simplified approach to stratifying risk is to determine whether the patient has definite acute coronary syndrome, probable acute coronary syndrome, or possible acute coronary syndrome, as follows4:

• Patients with definite acute coronary syndrome are those with (1) changes diagnostic of ischemia or infarction on an ECG, (2) diagnostic elevation of serum cardiac markers, or (3) evidence of new heart failure or shock directly attributable to an acute ischemic event.

• Patients with probable acute coronary syndrome are those in whom suspicion for acute coronary syndrome is high but definitive criteria are lacking. An example is a patient with a classic history for acute coronary syndrome or whose cardiac marker values are slightly elevated but still below the diagnostic cutoff and who does not have clear ECG evidence of ischemia.

• Patients with possible acute coronary syndrome constitute the majority of patients with chest pain. They have atypical histories, their ECG findings are normal or unchanged from previous studies, or suspected alternative causes are triggering their symptoms.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Historical and examination features that raise or lower the likelihood of acute coronary syndrome are described in Box 54.3 and Table 54.1. It is important to remember that the presence of lower-likelihood features does not exclude the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome. One study of patients with AMI found that 22% had sharp or stabbing pain and 13% had partially pleuritic pain.5

Box 54.3 Clinical Features of Patients with Chest Pain That Raise the Likelihood of Acute Myocardial Infarction

Table 54.1 Features of Chest Pain That Lower the Likelihood of Acute Myocardial Infarction*

| FEATURE | FREQUENCY IN PATIENTS WITH ACUTE ISCHEMIA (%) |

|---|---|

| Pleuritic pain | 13 |

| Pain that is reproducible with palpation or movement | 7 |

| Sharp, stabbing pain | 22 |

| Pain that lasts seconds or is constant for 24 hours or longer3 | NA |

NA, Not available

* Likelihood ratio of approximately 0.3.

The physical examination should be thorough, and findings suggestive of an alternative diagnosis may be helpful but are often not adequately specific to exclude acute coronary syndrome. For example, in 7% of patients with AMI, the pain is fully reproduced by palpation.5

Diagnostic Testing

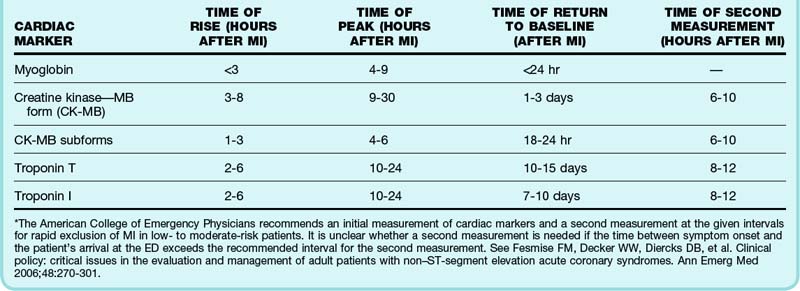

Current guidelines recommend the use of cardiac troponins for the evaluation of all patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Troponins, regulatory proteins found in cardiac muscle, are composed of three subunits: I, T, and C. Cardiac subunits I and T are genetically distinct from the skeletal muscle forms, and no cross-reactivity occurs on immunoassays. Within 2 to 8 hours of AMI, troponin levels are abnormal and remain so for 7 to 10 days (Table 54.2). Detectable troponin but at a value below the diagnostic cutoff for AMI still portends a higher risk for adverse outcomes.6 Nonspecific elevations, especially of troponin T, can occur with renal dysfunction, pulmonary embolism, septic shock, decompensated heart failure, myocardial contusion, pericarditis, and myocarditis. Cardiac troponins are more sensitive and specific than creatinine kinase, MB fraction (CK-MB), and myoglobin for cardiac muscle damage, and contemporary troponin assays identify the majority of AMIs within 3 hours, thus limiting the utility of CK-MB and myoglobin.

CK-MB is an enzyme present at higher percentages in cardiac muscle than in skeletal muscle, and it is relatively specific for cardiac muscle damage. False-positive results occur in patients with renal failure and in those with large amounts of skeletal muscle injury, such as seen with rhabdomyolysis. The CK-MB index improves the specificity of the biomarker by comparing the ratio of CK-MB with total CK. Levels higher than 5% are consistent with AMI, whereas those from 3% to 5% are indeterminate. CK-MB is detectable in blood 3 to 8 hours after myocardial infarction and returns to normal within 48 to 72 hours (see Table 54.2). The CK-MB subforms CK-MB1 and CK-MB2 rise earlier than CK-MB and are detectable 1 to 3 hours after injury, with a sensitivity of 92% achieved at 6 hours. Unfortunately, laboratory testing for CK-MB1 and CK-MB2 is not widely available.

Recommendations based on the best available evidence and consensus argue against using a single cardiac marker value within 6 hours of the onset of symptoms to exclude AMI. For patients initially seen more than 6 to 8 hours after onset of the most recent episode of pain, a single negative cardiac marker value is often adequate to exclude AMI (but not unstable angina) in those with possible acute coronary syndrome. A period of observation that includes repeated ECG and serum CK-MB and troponin measurements can be used to rapidly rule out AMI at 6 and 8 hours after the onset of symptoms, respectively (see Table 54.2). Some evidence shows that a more accelerated testing approach is appropriate when such testing is followed immediately by stress imaging. In fact, one investigation found that it was safe to test patients with chest pain on an exercise treadmill immediately without initially determining cardiac marker values. The patients involved in this study, however, were at extremely low risk, with normal or nearly normal ECG findings, no evidence of heart failure, and the ability to exercise, and they were found to have only a 1% rate of AMI.7

Observation Units and Protocols

After a period of observation, repeated cardiac marker testing, and either continuous or intermittent ECG monitoring, patients in whom the ECG findings are unremarkable and cardiac biomarker results are negative undergo stress testing. Guidelines recommend that the stress test be performed within 72 hours of ED discharge; a majority of published reports describe stress testing before discharge.3

Treatment

Patients with possible acute coronary syndrome should receive aspirin. In patients with ongoing ischemic symptoms, nitrates may be given. Nitrates have never been shown to improve outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome, and recently, the response to nitrates has been shown to lack predictive value in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome. Their use in these low-likelihood patients should be weighed against the risk for hypotension or even headache. Analgesics such as morphine are given to patients with discomfort unresponsive to nitrates. Controversy surrounds the use of β-adrenergic receptor blockers. Currently, routine administration of intravenous beta-blockers in the prehospital setting or ED is not recommended.8 Therapies such as heparin, clopidogrel, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been shown to be of benefit primarily in patients with definite acute coronary syndrome and therefore should not be used in this low-likelihood group.4

Disposition

It is important to acknowledge that the clinician cannot obtain perfect sensitivity in the assessment of patients with any disease. An analysis of multiple studies on acute coronary syndrome found that clinicians missed fewer AMIs when they admitted more patients.9 Clearly, there is a limit to this strategy, although evidence does suggest that providing resources to increase the number of patients undergoing evaluation may reduce the proportion of acute coronary syndrome that is missed. This appears to be a cost-effective approach but depends on multiple factors that may be outside the clinician’s and even the institution’s control. Even when clinicians are confident of an alternative diagnosis, subsequent adverse cardiac events may occur, with a 2.8% rate documented in one large study.10 The acceptable “miss rate” depends on the following factors:

Aortic Dissection

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The classic manifestation of aortic dissection is acute (with maximum intensity at onset), severe, tearing chest pain that radiates to the back in patients with a history of hypertension. On examination, patients may exhibit pulse deficits or an aortic insufficiency murmur. Unfortunately, the classic manifestation is the exception and the clinical spectrum is broad (Table 54.3). Symptoms frequently mimic more common disorders, and the clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion.11

Table 54.3 Frequency of Symptoms and Physical Findings in Patients with Aortic Dissection

| FEATURE | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Pain | 95 |

| Severe or worst ever | 90 |

| Abrupt onset | 85 |

| Location in chest | 75 |

| Location in chest and back or back alone | 50 |

| Tearing or ripping | 50 |

| Syncope | 10 |

| Physical Findings | |

| Hypertension | 50 |

| Aortic insufficiency murmur | 30 |

| Pulse deficit (pulse differences in the four extremities) | 15 |

| Hypotension | 5 |

Diagnostic Testing

Chest radiography alone is insufficient to exclude aortic dissection. However, normal findings on chest radiography significantly decrease the level of suspicion—as long as they are truly normal; only 12% of chest radiographs in patients who do have aortic dissection are retrospectively considered normal.11 In 78% of patients with aortic dissection, chest radiography demonstrates either a widened mediastinum or abnormal aortic contour. If possible, the EP should inform the radiologist that aortic dissection is under consideration to direct examination of the radiograph toward the pertinent abnormalities.

The following features are found on the chest radiographs of patients with aortic dissection:

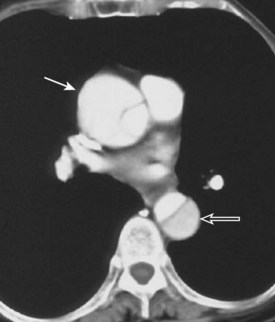

Helical computed tomography and echocardiography provide definitive testing for aortic dissection. Either diagnostic test is 95% to 100% sensitive; echocardiography is preferred when the patient is unstable because it can be performed in the critical care setting. Transthoracic echocardiography is extremely sensitive in detecting abnormalities of the aortic root and ascending aorta, whereas the transesophageal approach is required to exclude involvement of the arch or descending aorta (Fig. 54.1).

Cocaine-Associated Chest Pain

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported in 2002 that 33 million people 12 years and older (14.4% of the U.S. population) reported using cocaine at least once in their lifetimes. Cocaine abuse is not limited to a specific subset of the population and is frequently seen in ED patients, as demonstrated by an urban ED report that 2% of the institution’s patients 60 years and older tested positive for cocaine.12

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Inquiry should be made about recent cocaine use in all patients seen in the ED with chest pain. Patients who have used cocaine recently often have significant elevations in blood pressure in addition to their chest pain. They may be jittery and somnolent at the same time after having binged on crack cocaine. Studies have documented the incidence of AMI in patients with cocaine-associated chest pain to be approximately 6%. One study found that patients with cocaine-associated AMI were young (mean age, 38 years), tobacco smokers (91%), and nonwhite (72%) and had used cocaine within the proceeding 24 hours (88%).13 Nevertheless, a significant proportion of patients with cocaine-associated chest pain are older, and their risk for myocardial ischemia, though greatest in the first hours after the drug use, remains elevated for at least 2 weeks after discontinuation of the drug.

Medical Decision Making and Differential Diagnosis

The chest pain or dyspnea associated with cocaine use may stem from a variety of causes. In addition to acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection has been reported to be associated with cocaine use.14 The barotrauma induced by smoking crack cocaine results from deep inhalation followed by the Valsalva maneuver or severe coughing and leads to pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium. Pulmonary diseases associated with smoking cocaine include noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonia, asthma, interstitial lung disease, bronchiolitis obliterans–organized pneumonia, parenchymal hemorrhage, and pulmonary vascular disease. Musculoskeletal trauma may also occur.

1 Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1163–1170.

2 Kohn MA, Kwan E, Gupta M, et al. Prevalence of acute myocardial infarction and other serious diagnoses in patients presenting to an urban emergency department with chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:383–390.

3 Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116:e148–e304.

4 Tabas J, McNutt E. Treatment of patients with unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1027–1042.

5 Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg M, et al. Acute chest pain in the emergency room: identification and examination of low-risk patients. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:65–69.

6 Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Rifai N, et al. Ability of minor elevations of troponins I and T to predict benefit from an early invasive strategy in patients with unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: results from a randomized trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2405–2412.

7 Kirk JD, Turnipseed S, Lewis WR, et al. Evaluation of chest pain in low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department: the role of immediate exercise testing. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:1–7.

8 O’Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Acute coronary syndromes: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S787–S817.

9 Graff LG, Dallara J, Ross MA, et al. Impact on the care of the emergency department chest pain patient from the Chest Pain Evaluation Registry (CHEPER) study. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:563–568.

10 Miller CD, Lindsell CJ, Khandelwal S, et al. Is the initial diagnostic impression of “noncardiac chest pain” adequate to exclude cardiac disease? Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:565–574.

11 Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903.

12 Rivers E, Shirazi E, Aurora T, et al. Cocaine use in elder patients presenting to an inner-city emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:874–877.

13 Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Burstein JL, et al. Cocaine-associated myocardial infarction: mortality and complications. Cocaine-Associated Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1081–1086.

14 Hsue PY, Salinas CL, Bolger AF, et al. Acute aortic dissection related to crack cocaine. Circulation. 2002;105:1592–1595.