Chapter 34 Cervical Spine and Cervicothoracic Junction

Cervical and Nuchal Anatomy

An understanding of anatomy is the most basic tenet of surgery. Because both ventral and dorsal approaches are commonly used when operating on the cervical spine, it is essential that the spine surgeon be familiar with the anatomy of both the cervical and nuchal regions.1

Anatomic Overview of the Neck

Frick et al. have presented an overview of the anatomy of the neck with the cervical spine as the centerpiece.2 Dorsal to the cervical spine lies the nuchal musculature, which is covered superficially by two large muscles: the trapezius and the levator scapulae. Just ventral to the vertebral bodies lies the visceral space, which contains elements of the alimentary, respiratory, and endocrine systems. The visceral space is surrounded by the cervical musculature and portions of the cervical fascia. Dorsolateral to the visceral space but separated from the visceral space, as well as the cervical musculature, lie the paired neurovascular conduction pathways. Thus, in this scheme, the neck may be divided into five distinct regions: cervical spine, nuchal musculature, visceral space, cervical musculature, and neurovascular conduction pathways.

Surface Anatomy of the Neck

The prominent surface structure of the ventral neck is the laryngeal prominence, which is produced by the underlying thyroid cartilage. The thyroid cartilage is composed of two broad plates that are readily palpable. This cartilage protects the vocal cords, which lie at the midpoint of the ventral surface. Rostral to the thyroid cartilage lies the horseshoe-shaped hyoid bone, which is easy to palpate with the neck extended. The hyoid bone lies in the mouth-cervical angle3 and mediates the muscular attachments of the muscles of the floor of the mouth (middle pharyngeal, hyoglossus, and genioglossus muscles), as well as those of the six hyoid muscles (stylohyoid, thyrohyoid, geniohyoid, omohyoid, mylohyoid, and sternohyoid). The hyoid bone provides some movement during swallowing. This movement is limited caudally to the fourth cervical vertebral body by the stylohyoid ligament.2 The transverse process of the atlas may be palpated at a point marked by a line between the angle of the mandible and a point 1 cm ventrocaudal to the tip of the mastoid process.3

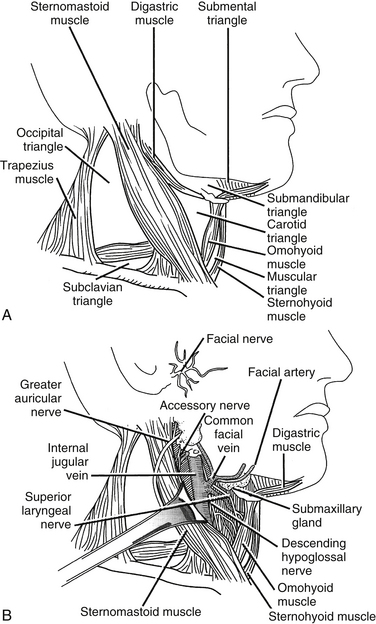

Triangles of the Neck

The sternocleidomastoid muscle divides the neck into two large triangles, posterior and anterior, which are then subdivided into two and four triangles, respectively. Knowledge of these triangles includes a definition of the borders and the contents of each triangle (Fig. 34-1).

FIGURE 34-1 A, Cervical triangles. B, Carotid triangle and its contents.

(Copyright University of New Mexico, Division of Neurosurgery, with permission.)

Posterior (Dorsal) Triangle

Caudal to the spinal accessory nerve are many important anatomic structures. The external jugular vein, which is formed by the confluence of the posterior auricular and the posterior division of the retromandibular vein at the angle of the mandible, courses over the sternocleidomastoid muscle obliquely to enter the dorsal cervical triangle caudally, en route to joining the subclavian vein approximately 2 cm above the clavicle.3 Two branches of the thyrocervical trunk cross the dorsal cervical triangle. The suprascapular artery runs rostral to the clavicle before passing deep to the clavicle to supply the periscapular muscles. The transverse cervical artery lies 2 to 3 cm rostral to the clavicle and also runs laterally across the dorsal cervical triangle to supply the periscapular muscles.

Anterior (Ventral) Triangle

The submental triangle is bounded by the hyoid body and laterally by the ventral bellies of the right and left digastric muscles. This triangle has, as its floor, the two mylohyoid muscles that connect to each other in the midline by forming a median raphe. Within this triangle lie the submental lymph nodes that drain the ventral tongue, the floor of the oral cavity, the middle portion of the lower lip and the skin of the chin, and several small veins that ultimately converge to form the anterior jugular vein.

The carotid triangle is bounded by the ventral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the rostral edge of the rostral belly of the omohyoid muscle, and the caudal edge of the dorsal belly of the digastric muscle. Within the carotid triangle lie the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein laterally, the vagus nerve dorsally, and the ansa cervicalis (see Fig. 34-1B).

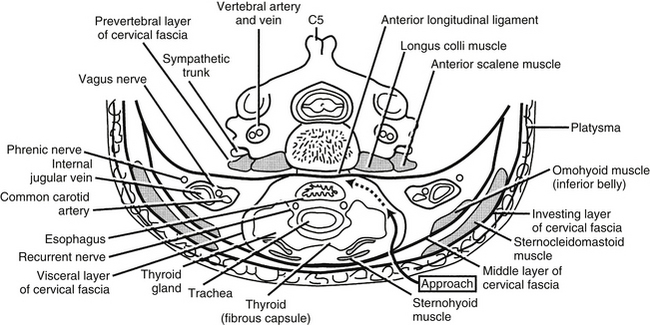

Cervical Fascia

An understanding of the cervical fascia aids the surgeon approaching a targeted cervical spine level by providing an avascular plane of dissection. There are three layers of the cervical fascia: investing, visceral, and prevertebral (Fig. 34-2). The investing fascia surrounds the entire neck, splitting to enclose the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles and the submandibular and parotid glands. Rostrally, the investing fascia is connected to the hyoid bone, caudal border of the mandible, zygomatic arch, mastoid process, and superior nuchal line. Caudally, the investing fascia splits to attach to the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the sternum, thus forming the suprasternal space.3 The investing fascia forms the roof of both the ventral and dorsal cervical triangles.

Cervical Sympathetic Chain

The cervical sympathetic chain (CSC) usually consists of three cervical ganglia that lie at the levels of the first rib, the transverse process of C6, and the atlantoaxial complex, respectively. The CSC lies directly over the longus colli muscles and beneath the prevertebral fascia.4 The chain runs in a superior and lateral direction with an average angle of 10.4 ± 3.8 degrees relative to the midline.4 The superior ganglion is typically located at C2-34 or C45 and lies more laterally on the splenius capitis. The average distance between the CSC and the medial border of the longus colli muscles at C6, however, is 10.6 ± 2.6 mm.4 Therefore the CSC is considerally more vulnerable to damage at lower levels due to its more medial location. While the longus colli diverge laterally when descending down the cervical spine, the CSCs converge medially at C6.4 The average diameter of the CSC at C6 is 2.7 ± 0.6 mm.4 Potential damage to the CSC may result during longus colli dissection off the anterior vertebral bodies or during lateral rectraction of the carotid sheath and/or longus colli.4 Fibers from the superior cervical ganglia pass to the internal carotid artery to innervate the pupil. Interruption of the sympathetic trunk in the neck results in an ipsilateral Horner syndrome.

Cervical Musculature

The cervical musculature is divided into two layers: superficial and deep. The muscles of the superficial layer include the platysma, the sternocleidomastoid, and the infrahyoid group. The platysma lies just under the surface of the skin and is one of the muscles of facial expression, innervated by the cervical ramus of the seventh cranial nerve. It is draped like an apron from the mandible to the level of the second rib and laterally as far as the acromion processes. The sternocleidomastoid muscle arises from the region of the jugular notch and courses rostrolaterally to the mastoid process. It is dually innervated by the 11th cranial nerve and ventral branches of the C2-4 spinal nerves. The spinal accessory nerve enters the deep surface of the muscle at the border of the middle and rostral thirds. The two main actions of the sternocleidomastoid muscle are to turn the head to the contralateral side and to flex the head ipsilaterally. The infrahyoid group represents the rostral continuation of the rectus muscular system of the trunk.2 This group contains four muscles: sternohyoid, sternothyroid, omohyoid, and thyrohyoid. The first three members of this group are innervated by the ansa cervicalis, and the thyrohyoid receives its innervation from the C1 spinal nerve via the hypoglossal nerve. The main actions of the infrahyoid group are to assist in swallowing and mastication. This group, together with the suprahyoid group, determines the rostrocaudal location of the larynx between the hyoid bone and the rostral thoracic aperture and can help flex the cervical spine and lower the head.

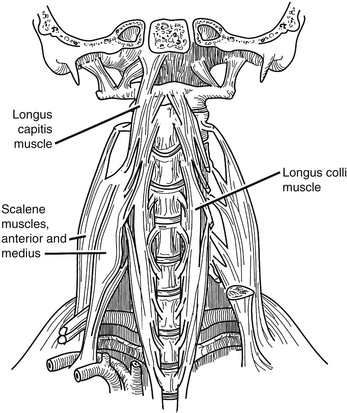

The deep layer of cervical musculature includes two groups: scalene and longus groups. The scalene group includes three muscles: anterior, medius, and posterior. These muscles form a roof over the cupula of the lung. As a group, these muscles arise from the transverse processes of the subaxial cervical spine and project to the first and second ribs. The scalene muscles are innervated by the ventral rami of C4-8. They help to elevate the rib cage during respiration. The longus group also includes three muscles: rectus capitis anterior, longus capitis, and longus colli (Fig. 34-3). As a group, these muscles arise from the ventral vertebral body, transverse processes, and basilar portion of the occiput. They project caudally along the ventrolateral aspects of the cervical and upper thoracic vertebral bodies. These muscles are innervated by the ventral rami of C1-6, and their main action is to flex the head and the cervical spine.

Longus Colli

The longus colli attach to the anterior atlas, the vertebral bodies of C3-T3, and the transverse processes of C3-6.6 The distance between the medial borders of the longus colli muscles increases in a rostral to caudal direction, measuring 7.9 ± 2.2 mm at C3, 10.1 ± 3.1 mm at C4, 12.3 ± 3.1 mm at C5, and 13.8 ± 2.2 mm at C6.6 A great deal of variation exists in this musculature, so care should be taken in using it as a landmark for lateral dissection.

Cervical Viscera

The pharynx is a fibromuscular tube that projects from the pharyngeal tubercle of the clivus to its transition into the esophagus near the level of C6. The dorsal surface of the pharynx lies on the prevertebral fascia and must be mobilized during ventral approaches to the cervical spine. The muscles of the pharynx may be divided into two groups: constrictors and internal muscles of the pharynx. The constrictor group includes three muscles whose main action is to sequentially constrict the pharynx during swallowing, propelling food caudally. All of the constrictors are innervated by the pharyngeal plexus, which receives its branches from both the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The constrictors do not form a continuous tube but are open at four points, allowing certain structures to pass into the pharynx. Rostral to the superior constrictor, the ascending palatine artery, the eustachian tube, and the levator veli palatini muscles pass to enter the pharynx. Between the superior and inferior constrictors pass the glossopharyngeal nerve, the stylohyoid ligament, and the stylopharyngeus muscle. In the gap between the middle and inferior constrictors pass the internal laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal artery and vein. Caudal to the inferior constrictor pass the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the inferior laryngeal artery. The internal muscle groups of the pharynx have a common function of elevating the larynx and pharynx during swallowing and a common innervation by the glossopharyngeal nerve. At the level of C6, the pharynx blends into the esophagus, which passes through the superior thoracic aperture to the stomach. In the root of the neck, the esophagus is in close approximation to the thoracic duct as it empties into the left subclavian vein.

Thoracic Duct

The thoracic duct is located on the left side within a triangle bounded medially by the longus colli muscles and the esophagus, laterally by the anterior scalene muscle, and inferiorly by the first rib.7,8 Although it may ascend as high as C6, it is most often found between C7 and T1, before it descends to empty into a variable termination at the jugulosubclavian junction.7,8 The rostral extension of the thoracic duct appears to vary by gender, as in patients who have a narrow thoracic inlet, as most women do, the duct may ascend as high as the level of the C6 vertebral body. Conversely, in patients who have a wide thoracic inlet, as most men do, the duct may ascend to the level of the C7-T1 disc, never truly leaving the mediastinum. Many have cited the increased possibility of injuring this structure in the left upper thorax as a reason for preferring a right-sided approach, especially to the upper thoracic vertebrae.7

Laryngeal Nerves

The vagus nerve, or cranial nerve X, emerges from the brainstem, exits the intracranial space via the jugular foramen, and passes through the neck, chest, and abdomen, where it contributes to the innervation of the viscera. In the cervical region, both the right and left vagus nerves lie within the carotid sheath, lateral to the carotid artery. Near its passage through the thoracic inlet, the vagus nerve branches, giving rise to the recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLNs), which subsequently ascend toward the larynx. Before doing so, however, each RLN assumes a different course. The right RLN leaves the main trunk of the vagus and passes anterior to and then under the subclavian artery. This loop occurs at the T1-3 level. Meanwhile, the left RLN passes under and posterior to the aorta at the site of origin of the ligamentum arteriosum, a loop that is found at the T3-6 level.9 The right RLN also courses rostrally in a more oblique fashion (in a superior and medial direction at an angle of 25 ± 4.7 degrees relative to the sagittal plane) than the left RLN (4.7 ± 3.7 degrees).9 In the neck, the left RLN lies in the tracheoesophageal groove, entering at the midpoint of its course. The right RLN, however, lies 6.5 ± 1.2 mm anterior and 7.3 ± 0.8 mm lateral to the tracheoesophageal groove at C7, with high variability at this site and throughout its course.9 The left RLN, therefore, is better protected from iatrogenic injury. Anatomic variations of the RLN such as nonrecurrence on either side or the nerves’ entering the larynx directly after their takeoff from the vagus are overall extremely rare.9

Nearing their entrance into the laryngeal structures at C5-7, the RLNs lie in close association with the inferior thyroid arteries (ITAs). The RLN length between the superior margin of the clavicle and the ITA is 23 ± 4.4 mm on the left and 22.8 ± 4.3 mm on the right.9 The RLNs’ relation to the ITA branches, however, is highly variable; on the right, the RLN is more commonly found anterior (26–33% of the time) or between the arterial branches, whereas on the left, the RLN is more commonly posterior (50–55%).9

Although unilateral RLN palsy is reported to be the most common nerve-related injury after anterior cervical surgery, the overall incidence of the resultant hoarseness is relatively low at 2% to 4%. This may be avoided by recognizing the sites at which the RLN is most vulnerable. The nerve is susceptible to injury if the dissection plane is not maintained entirely medial to the carotid sheath, if the longus colli dissection is not limited to the area between the muscle and the vertebrae, or if the dissection is carried superficial to the esophagus.7 As mentioned earlier, the right RLN is vulnerable to injury if ligation of the inferior thyroid vessels is not performed as laterally as possible or with prolonged retraction without intermittent interruption.9 The superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) originates from the inferior vagal ganglion at the C2 level and then descends medially toward the thyrohyoid membrane.10 At the C3 level, the SLN branches into external and internal branches deep to the internal carotid artery.10,11 The external branch of the SLN (EBSLN) travels with the cricothyroid artery and descends deep to the superior thyroid artery (STA) toward the cricothyroid muscle.10 The internal branch travels with the superior laryngeal artery and passes deep to a loop of the STA before piercing the thyrohyoid membrane.10,12 Both the external and internal branches of the SLN are within the fascia overlying the longus colli muscles.11

Conduction Pathways

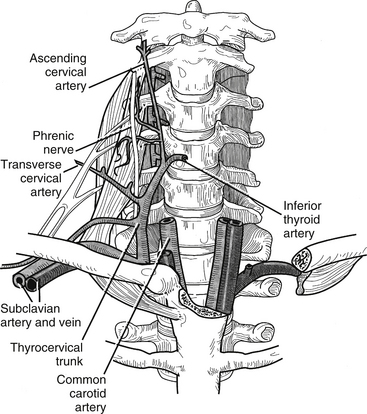

The neck has two major neurovascular conduction pathways: cervicocranial and cervicobrachial (Fig. 34-4). The cervicocranial neurovascular bundle is outlined by the carotid sheath, which contains the common carotid artery medially, the internal jugular vein laterally, the vagus nerve dorsally, and the lymphatic plexus. As a whole, the cervicocranial neurovascular bundle lies laterally to the visceral space and ventrally to the prevertebral fascia. The bundle passes rostrally from the thorax and enters the carotid triangle, where the common carotid artery bifurcates into the internal carotid artery dorsolaterally and the external carotid artery ventromedially.

FIGURE 34-4 The conduction pathways.

(Copyright University of New Mexico, Division of Neurosurgery, with permission.)

The other major neurovascular conduction pathway is the cervicobrachial pathway, which supplies the upper extremities. The subclavian artery and the components of the brachial plexus exit the neck over the first rib and between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and then proceed through the posterior triangle of the neck to enter the axilla. The subclavian artery gives off the following arteries: vertebral, thyrocervical, internal thoracic, costocervical, and dorsal scapular. The vertebral artery is the vessel of most interest to the spine surgeon (Fig. 34-5). It arises from the dorsal aspect of the subclavian artery and courses medial to the anterior scalenus to enter the foramen transversarium of the sixth cervical vertebra. It then ascends in the foramen transversarium until the level of the axis, where it courses medially in a groove bearing its name and through the atlanto-occipital membrane to enter the cranial cavity. The subclavian vein runs ventral to the artery and to the scalenus anterior muscle just under the clavicle.

Vertebral Artery

The vertebral artery (VA) usually originates from the subclavian, or innominate, artery on the right and the aortic arch on the left. The artery is typically divided into four anatomic segments: the first segment, V1, consists of the artery’s origin to the C6 transverse foramen; the second segment, V2, passes cranially from the C6 to the C2 transverse foramen; the third segment, V3, exits C2 and extends to the level of the foramen magnum; and the final portion, V4, passes through the foramen magnum and reaches to the vertebrobasilar junction.13

Due to the frequency of operative procedures in the subaxial spine, the anatomy of the V2 segment has been thoroughly reviewed. After ascending cranially, V1 passes by the transverse process of C7 anteriorly and laterally before entering the transverse foramen of C6.14 V2 then extends from the artery’s entry into the C6 foramen to the transverse foramen of C2.15 In 94.9% of specimens, C6 is the first transverse foramen entered, but variations do exist (C4 in 1.6%, C5 in 3.3%, and C7 in 0.3%).13 Within the intertransverse space, the vertebral artery and nerve root are encased in a fibroligamentous band. This band is attached to the lateral aspect of the uncinate process and the uncovertebral (UV) joint, combining the artery, nerve root, and uncinate process as a unit.16 Before resection of the uncinate process or UV joint (i.e., uncoforaminotomy), it is necessary to dissect this fibroligamentous tissue off of the uncinate process.16 In addition, it must be noted that the posterior and medial portion of the VA gives rise to numerous spinal and muscular branches in the intertransverse space.15,17

For a number of reasons, the V2 segment of the vertebral artery is more at risk during decompression of more cephalad vertebrae.14,16,17 First, the diameter of the artery decreases from C2-3 to C6-7 (4.88 ± 0.63 mm at C2-3 to 4.27 ± 0.63 mm at C6-7),17 and the anteroposterior diameters of the transverse foramina decrease from C6 to C3 (5.4 ± 1.1 mm at C6 to 4.7 ± 0.7 mm at C3).14 The amount of the intertransverse space occupied by the artery, therefore, increases at more rostral levels.17 Second, the artery ascends medially from C6-3 at an angle of approximately 4 degrees relative to midline, making it more likely to be encountered in the surgical field at higher cervical levels.18 Finally, a series of other relationships places the VA at greater risk of iatrogenic injury at more cephalad levels. These include decreased interforaminal distance (27.4 mm ± 2.3 mm at C6 to 22.6 ± 1.8 mm at C3), width of the vertebrae (25.6 ± 2 mm at C7 to 19.2 ± 1.8 mm at C3), interuncinate distance (24.6 ± 2.1 mm at C7 to 19.2 ± 1.5 mm at C3), and distance from the lateral tip of the uncinate process to the medial border of the transverse foramen (3.3 ± 1 mm at C6 to 1.7 ± 0.8 mm at C4) at higher levels.14 In addition, it should also be noted that because the vertebral artery is more anterior at C6 and becomes more posterior as it travels toward C3, there is greater risk with anterolateral uncinate resection in more caudad levels and with posterolateral decompression in more cephalad levels.19

Three possible risk factors have been identified for vertebral artery injury: motorized dissection with a high-speed diamond burr used off midline, excessive lateral dissection of bone and disc, and the bone of the lateral part of the spinal canal being pathologically softened by infection or tumor.20 Intraoperative VA injury can be largely avoided by following a number of guidelines. If far lateral decompression is necessary, the anterior wall of the transverse foramina should be removed, the vertebral artery retracted laterally, and small rongeurs and curettes used, rather than a high-speed drill.14,16 In performing foraminotomies, lateral dissection can generally be carried safely to the medial margin of the UV joint in most patients. Care should be taken, however, when extending farther laterally and should likely not exceed 5 to 6 mm beyond the nerve root’s emergence from the thecal sac.19 This is because the posterior surface of V2 rests on the anteromedial aspect of the cervical nerve roots at each level of the intertransverse space, and the mean length of the nerve root between the dural sac and the VA is 6.3 ± 1.06 mm.15

In posterior approaches, injury to the vertebral artery is more common than in ventral surgery. Whereas in anterior cervical procedures, the artery is most at risk during osseous decompression, the placement of posterior instrumentation is the portion of that procedure during which there is greatest risk for VA injury. It is, therefore, important to recognize the artery’s relationship to the osseous structures of the posterior column. The shortest distance from the artery to the cervical pedicle increases from C3 to C5 (0.5 ± 0.2 mm at C3, 1.1 ± 0.4 mm at C4, 1.4 ± 0.8 mm at C5), decreases at C6 (0.9 ± 0.5 mm), and then dramatically increases at C7 (7.3 ± 2.7 mm).21 As the VA emerges from the C2 transverse foramen, it travels in a groove extending horizontally from the medial border of the transverse foramen to the medial edge of the posterior ring.19 To avoid injury, exposure of the posterior ring of the atlas should remain medial to that groove.19 In about 80% of patients, the VA makes an acute lateral bend in the C2 lateral mass just under the superior articular facet.19 If the trajectory of a C1-2 transarticular screw is aimed too low, the VA may be injured here.19 In C2 pedicle screws, lateral perforation of the pedicle puts the VA at risk, and in C1 lateral mass screws, the VA is vulnerable near its exit from the C2 transverse foramen where it lies in close proximity to the C1 lateral mass.19

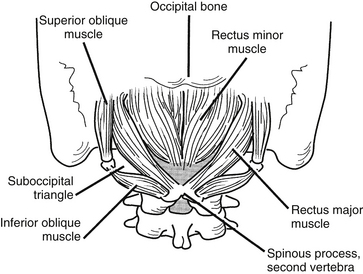

Nuchal Musculature

The intrinsic musculature of the dorsal neck may be divided into three layers: superficial, intermediate, and deep (Fig. 34-6). All of these muscles are innervated by the dorsal rami of several consecutive spinal nerves. The superficial layer contains the splenius capitis and the splenius cervicalis, which take their origin from the ligamentum nuchae and the spinous processes of C6-T1. The splenius capitis inserts along the lateral third of the superior nuchal line and on the mastoid process. The splenius cervicalis muscle inserts into the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C1-4. These muscles produce extension, lateral bending, and rotation of the head or neck.

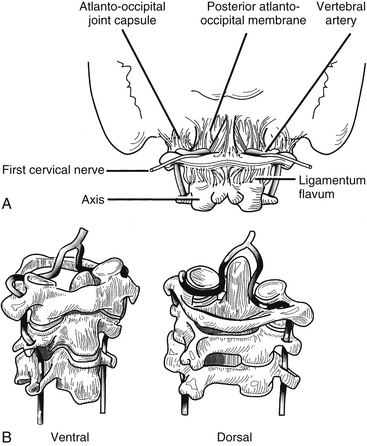

Spinal Anatomy

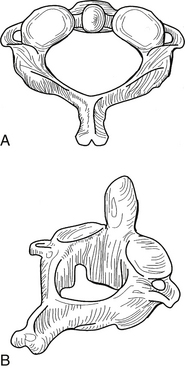

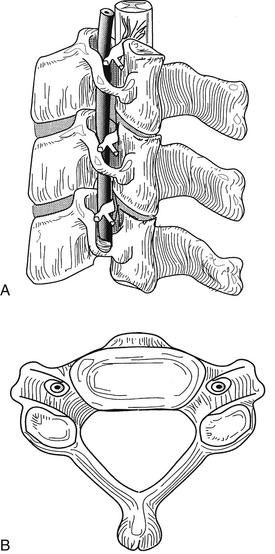

The upper cervical spine is characterized by the axis and its “anatomic neighbors” (Fig. 34-7). The subaxial cervical spine varies minimally from level to level and is discussed as a single unit (Fig. 34-8). The components of the subaxial vertebrae include the body, upper and lower articular processes, pedicles, lamina, and spinous process. The vertebral bodies are the axial load-bearing elements of the spine. In the subaxial cervical spine the vertebral body height increases as the spine is descended with a slight reversal of this relationship at C6, which is usually shorter than either C5 or C7. Each body has a dorsally directed concavity that forms the ventral spinal canal. From each body arise three body projections: rostrally the uncus, laterally the ventral ramus of the transverse process, and dorsolaterally the pedicle.

FIGURE 34-8 The subaxial spine. A, Lateral view; B, axial view.

(Copyright University of New Mexico, Division of Neurosurgery, with permission.)

The rostral aspect of each of the lower cervical vertebral bodies contains the uncus, a dorsolateral bony projection. The uncus gives the body a rostrally concave shape in the coronal plane and enables the vertebral body to receive the rounded caudal aspect of the immediately adjacent vertebral body, sometimes overlapping the next level by a third of the vertebral body height. The uncovertebral joints limit lateral translation and contribute to the coupling of lateral bending and rotation of the cervical spine.

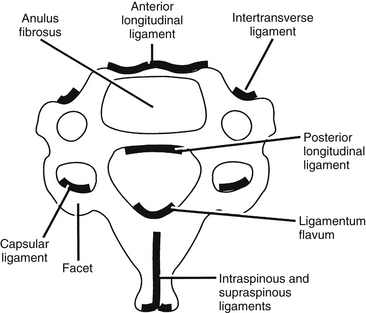

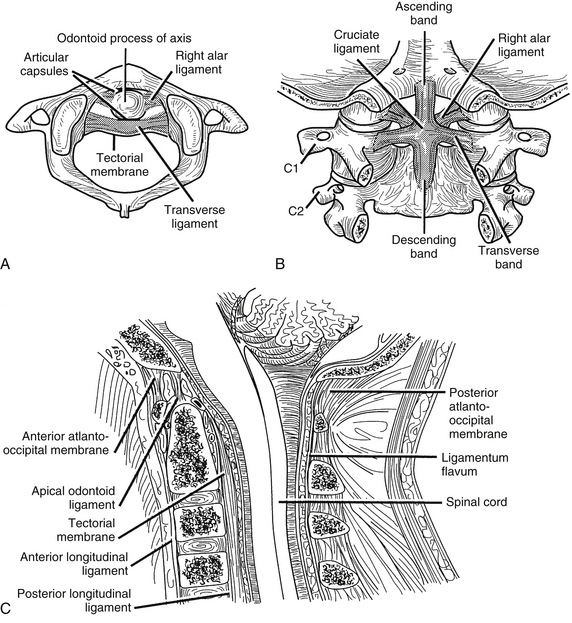

Ligaments

The ligaments of the cervical spine are essential for the maintenance of alignment and stability. The ligaments of the subaxial spine include the anterior longitudinal ligament, the posterior longitudinal ligament, the interspinous ligament, the supraspinous ligament, the capsular ligaments, the ligamentum flavum, and the intertransverse ligaments (Figs. 34-9 and 34-10). The anterior longitudinal ligament is attached to the ventral surfaces of the vertebral bodies and the intervening discs. It spans the entire length of the spine from the skull base to the sacrum. The main biomechanical feature of the anterior longitudinal ligament is resistance of hyperextension. The superficial fibers extend for four or five vertebral bodies, and the deep fibers span two vertebral bodies.

FIGURE 34-9 Ligaments of the cervical spine: A, axial, B, dorsal (after laminectomy), and C, midsagittal views.

(Copyright University of New Mexico, Division of Neurosurgery, with permission.)

Ligamentum Nuchae

The ligamentum nuchae (LN) is a triangle-shaped intervertebral syndesmosis, a bilateral fibroelastic intermuscular septum interposed between paired groups of paravertebral muscles of the cerviconuchal region.22 It is formed by the aponeurotic fibers of the trapezius, splenius capitis, rhomboideus minor, and serratus posterior superior muscles.23 Functionally, the LN serves to maintain lordotic alignment and stabilize the head during rotation of the cervical region.22 Extending from the external occipital protuberance, or inion, to the spinous process of C7, it is covered by layers of cervical fascia and the aponeurosis of the trapezius muscle.22 During posterior exposure of the cervical spine and suboccipital region, it is important to identify and maintain the dissection plane within the LN in order to minimize tissue damage, blood loss, and the possibility of injury to lateral structures such as the vertebral arteries.

The LN consists of two components: the lamellar portion ventrally and the funicular portion dorsally. The latter is a fibrous raphe that corresponds to the fusion of the underlying layers of the lamellar portion. The dorsal component is attached to the inion and the C7 spinous process and is freely mobile between these two structures.24 The lamellar portion is a double-layered midine septum with fatty areolar tissue interposed between its layers. It inserts into the medial side of the cervical vertebra’s bifid spinous processes.22 Attached rostrally at the inion and external occipital crest, the lamellar portion is superficial at C6-7 and deepest at C1.22,24 Anteriorly, it seems to be continuous with the interspinous ligament, suboccipitally with the atlanto-occipital and the atlantoaxial membranes, as well as the posterior spinal dura, and rostrally with the periosteum of the occipital bone.22,25 Although it is laterally continuous with the deep fascia of the semispinalis capitis and the splenius capitis, a cleavage plane separates the adjacent semispinalis capitis, allowing for a relatively easy intraoperative division.24

To ensure that the midline plane is respected with a posterior dissection, three strategies should be used: (1) Dissection should be maintained within the fatty areolar tissue of the LN’s lamellar portion; (2) isolation and incision of the funicular portion should be carried from inside to outside; and (3) retrograde dissection of the cerviconuchal muscles attached to the occipital bone should be performed in a subperiosteal plane.22

Intervertebral Foramen

The cervical spinal nerves exit from the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramen. True foramina, with four distinct walls, are found in the subaxial cervical spine, and partial foramina are present at the atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial levels.

Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Haman S.P., Yeasting R.A. Anatomic basis of the anterior surgery on the cervical spine: relationships between uncus-artery-root complex and vertebral artery injury. Surg Radiol. 1998;20:289-292.

Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Heck B.E., Yeasting R.A. Vulnerability of the sympathetic trunk during the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1603-1606.

Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Martin S., et al. Vulnerability of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2664-2667.

Hart A.K., Greinwald J.H., Shaffrey C.I., Postma G.N. Thoracic duct injury during anterior cervical discectomy: a rare complication. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:151-154.

Lu J., Ebraheim N.A., Georgiadis G.M., et al. Anatomic considerations of the vertebral artery: implications for anterior decompression of the cervical spine. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:233-236.

Mercer S.R., Bobgduk N. Clinical anatomy of ligamentum nuchae. Clin Anat. 2003;16:484-493.

1. Alexander J.T. Cervical spine and skull base anatomy. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Surgical exposures of the spine: an extensile approach. Park Ridge, IL: AANS; 1995:1-19.

2. Frick H., Leonhardt H., Starck D. Human anatomy 1. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1991.

3. Lang J. Clinical anatomy of the cervical spine. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1993.

4. Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Heck B.E., Yeasting R.A. Vulnerability of the sympathetic trunk during the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1603-1606.

5. Civelek E., Karasu A., Cansever T., et al. Surgical anatomy of the cervical sympathetic trunk during anterolateral approach to cervical spine. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:991-995.

6. Lu J., Ebraheim N.A., Georgiadis G.M., et al. Anatomic considerations of the vertebral artery: implications for anterior decompression of the cervical spine. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:233-236.

7. Gieger M., Roth P.A., Wu J.K. The anterior cervical approach to the cervicothoracic junction. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:704-710.

8. Hart A.K., Greinwald J.H., Shaffrey C.I., Postma G.N. Thoracic duct injury during anterior cervical discectomy: a rare complication. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:151-154.

9. Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Martin S., et al. Vulnerability of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2664-2667.

10. Monfared A., Kim D., Jaikumar S., et al. Microsurgical anatomy of the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:925-933.

11. Kochilas X., Bibas A., Xenellis J., Anagnostopoulou S. Surgical anatomy of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and its clinical significance in head and neck surgery. Clin Anat. 2008;21:99-105.

12. Ozlugedik S., Acar H.I., Apaydin N., et al. Surgical anatomy of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. Clin Anat. 2007;20:387-391.

13. Hong J.T., Park D.K., Lee M.J., et al. Anatomical variations of the vertebral artery segment in the lower cervical spine: analysis by three-dimensional computed tomography angiography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2422-2426.

14. Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Brown J.A., et al. Vulnerability of vertebral artery in anterolateral decompression for cervical spondylosis. Cin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:146-151.

15. Paolini S., Lanzino G. Anatomical relationships between the V2 segment of the vertebral artery and the cervical nerve roots. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:440-442.

16. Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Haman S.P., Yeasting R.A. Anatomic basis of the anterior surgery on the cervical spine: relationships between uncus-artery-root complex and vertebral artery injury. Surg Radiol. 1998;20:289-292.

17. Kawashima M., Tanriover N., Rhoton A.L., Matsushima T. The transverse process, intertransverse space, and vertebral artery in anterior approaches to the lower cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:188-194. (Suppl 2)

18. Lu J., Ebraheim N., Georgiadis G., et al. Anatomic considerations of the vertebral artery: implications for anterior decompression of the cervical spine. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:233-236.

19. Peng C.W., Chou B.T., Bendo J.A., Spivak J.M. Vertebral artery injury in cervical spine surgery: anatomical considerations, management, and preventive measures. Spine J. 2009;9:70-76.

20. Smith M.D., Emery S.E., Dudly A., et al. Vertebral artery injury during anterior decompression of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;[Br] 75:410-415.

21. Zhao L., Xu R., Hu T., et al. Quantitative evaluation of the location of the vertebral artery in relation to the transverse foramen in the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:373-378.

22. Kadri P.A., Al-Mefty O. Anatomy of the nuchal ligament and its surgical applications. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:301-304.

23. Johnson G.M., Zhang M., Jones D.G. The fine connective tissue architecture of the human ligamentum nuchae. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:5-9.

24. Mercer S.R., Bobgduk N. Clinical anatomy of ligamentum nuchae. Clin Anat. 2003;16:484-493.

25. Dean N.A., Mitchell B.S. Anatomic relation between the nuchal ligament (ligamentum nuchae) and the spinal dura mater in the craniocervical region. Clin Anat. 2002;15:182-185.