Chapter 115 Cervical Dystonia and Spasmodic Torticollis

Indications and Techniques

History of Dystonic Conditions

One of the earliest descriptions of dystonia was recorded by Gowers in 1888.1 Destarac in 1901 used the term “torticollis spasmodique” to describe the twisting neck movements observed in a 17-year-old girl. Dystonic conditions were identified as distinct from other hyperkinesias by Schwalbe in 1908; however, because of the bizarre nature of the movements, dystonias were originally considered a form of “hysterical neurosis.”

The term dystonia itself was first coined by Oppenheim in 1911, who was the first to correctly identify the organic nature of dystonia.2 However, focal dystonias, unlike the generalized condition, have been recognized for centuries. For example, the first recorded case of surgery for spasmodic torticollis dates back to 1641, when the German physician Minnius treated torticollis by sectioning the sternocleidomastoid muscle.1

In 1944, the pioneering work of Herz revived the concept of dystonia being an organic disease, concluding from his frame-by-frame analysis of moving pictures showing that dystonic movements were slow, long-sustained, powerful, and nonpatterned contortions of axial and appendicular muscles. However, because of failures to identify associated brain lesions, arguments for an organic basis of the condition were not recognized until Marsden et al. studied cases of patients with hemidystonia.3 They discovered that lesions in the putamen, caudate nucleus, and posterior ventral thalamus were commonly present, contralateral to the hemidystonia. In the 1980s and 1990s, investigation into generalized dystonia, particularly among Jews of Ashkenazi descent, led to the discovery of the DYTI gene mutation at the 9q34 locus. Since then, continued research has led to the awareness of a complex array of etiologic causes underlying dystonia, giving rise to an elaborate classification system for differentiating between dystonic conditions.

Epidemiology

Dystonic conditions are not rare. Epidemiologic surveys estimate that dystonia is the third most common movement disorder after Parkinson’s disease (PD) and essential tremor,4 considerably more prevalent than a number of better-known neurologic conditions such as myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, and motor neuron disease. In contrast to many other conditions, however, there have been few published epidemiologic studies of dystonia. Differences in study design have further confused prevalence estimates, making it difficult to extrapolate data from certain studies to the general population. Combined estimates of around 330 per million have been made, encompassing all dystonias,5 with approximately one third of all cases being due to cervical dystonia (CD). One of the most comprehensive examinations of prevalence estimates currently available was provided by the Epidemiological Study of Dystonia in Europe collaborative group,6 which estimated CD prevalence at 57 per million. However, true prevalence is unknown, with many authors suggesting that estimates in published reports are considerably lower than the actual prevalence7 due to significant numbers of undiagnosed cases within the community. This has implications with regards to the provision of patient care, particularly with respect to financing medical and surgical therapies for dystonic conditions.

Classification and Etiology

Etiologic Classification of Dystonic Conditions

An important aspect of the clinical evaluation of dystonia is the etiologic classification of the condition. This helps in formulating treatment strategies and deciding on the need for genetic counseling, and it may aid our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of the illness. To assist the etiologic classification of dystonic conditions, a similar system for the classification of parkinsonism has been adopted by many4 to include the subcategories of primary dystonia, dystonia-plus, secondary dystonia, and heredodegenerative diseases in which dystonia is the prominent feature. The molecular classification of dystonia includes several genetic loci. Currently 18 gene loci have been described,8 although it is likely that many more dystonia genes have yet to be discovered.

Primary Dystonia

Primary dystonia refers to those individuals in whom dystonia is the sole phenotypic manifestation, with the exception that the condition can sometimes be accompanied by tremor. There is no history of brain injury, laboratory findings to suggest a cause for dystonia, consistent associated brain pathology, or improvement following a trial of levodopa therapy. Age at onset displays a biphasic distribution, peaking at 9 years in the early-onset group and 45 years in late-onset patients.9 Early-onset primary dystonia tends to begin in one of the limbs and later progresses to other limbs and the trunk, most often leading to a severe generalized form of the disease. Late-onset primary dystonia usually commences in the upper body, most often the cranial–cervical region, and tends to remain focal or segmental. Early-onset primary dystonia (DYT1 dystonia) is often inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance. The genetics of late-onset primary dystonia are more complex than those of the early-onset form, although it appears that, similar to the early-onset form, inheritance occurs in an autosomal dominant fashion.10,11

Secondary Dystonia

Secondary dystonias comprise an array of conditions leading to dystonia. They arise from injuries or abnormalities of the nervous system, including brain injury due to external factors or acquired diseases. There is often an association with pathologic lesions of the basal ganglia, in particular the putamen.12 Lesions in the cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, brain stem, and spinal cord have also been reported to produce dystonia.13 It is important to recognize that dystonia may appear long after the insult and may be progressive.14

Cervical Dystonia

CD is the most common form of focal dystonia, occurring at any age but most frequently around 50 years and more often in women compared with men.13 Involuntary contractions of the neck muscles lead to a variety of abnormal head movements and postures. Spasmodic torticollis is the most common form of CD, resulting from predominantly rotational head posturing. Other types include anterocollis, retrocollis, lateral flexion, lateral or sagittal shift, and shoulder elevation or more complex configurations of posturing. In some patients, the dystonic jerks may be rhythmic and produce a jerky type of tremor, which can often be confused with essential tremor. With time, the rhythmic jerking is often superimposed on or replaced by abnormal posturing. Neck pain is a commonly associated symptom and occurs in about three quarters of patients. CD spreads to become segmental in some patients, but it rarely becomes generalized. Spontaneous remissions are observed in 10% to 20% of patients but are usually not sustained.13

Most cases of CD are idiopathic, although a careful history may reveal a familial history of other movement disorders, including other dystonias such as writer’s cramp or tremor. Although secondary CD is relatively uncommon, a careful and thorough neurologic evaluation is necessary to look for other possible underlying etiologies (Table 115-1).

| Psychogenic dystonia |

| Pseudodystonias |

| Congenital postural torticollis |

| Sandifer syndrome |

| Posterior fossa tumors |

| Chiari malformation |

| Syringomyelia |

| Stiff-person syndrome |

| Isaac’s syndrome |

| Satoyoshi syndrome |

| Congenital Klippel-Feil syndrome |

| Vestibular torticollis |

| Trochlear nerve palsy |

| Herniated cervical disc |

| Atlantoaxial subluxation |

| Infectious causes/abscess |

Treatment Strategies

One of the first general considerations in approaching the treatment of a patient with dystonia is to differentiate between the primary and the secondary dystonias. In a minority of patients with secondary dystonia—for example, Wilson’s disease, drug-induced dystonia, or dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD)—benefit can be gained from specific treatments.15 For example, all patients with childhood-onset dystonias should receive a trial of l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA), as this brings about dramatic improvement after a short period in those with DRD. For other patients, therapy is directed at controlling the symptoms rather than the cause, with different management strategies employed for generalized as opposed to focal conditions. As a rule, in patients with generalized and multifocal disease, oral pharmacotherapy constitutes the mainstay of treatment.

Unfortunately, treatment of dystonic conditions with oral agents is generally unsatisfactory. In addition to l-DOPA, other established medications include anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and baclofen. Except in the case of DRD, anticholinergic medications such as trihexyphenidyl are arguably the most effective pharmacotherapy for dystonia.16 Effective treatment with anticholinergics is sometimes limited by the development of side effects, including dry mouth, urinary retention, blurred vision, confusion, memory loss, and hallucinations. Although considered less effective than anticholinergics, baclofen has proved efficacious in children.17 Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam are also often employed and are particularly useful in the treatment of myoclonic dystonia.18 The dopamine-depleting drug tetrabenazine is considered effective in the treatment of some patients with tardive dystonia. Other antidopaminergics, such as haloperidol, may be effective but may also worsen symptoms or induce tardive dyskinesia and hence are not recommended. Although atypical neuroleptics such as clozapine have been suggested for the treatment of tardive dystonia, their effectiveness in treating other forms of dystonia remains questionable, and there are potentially very serious adverse effects associated with clozapine treatment, including agranulocytosis.19 Several other forms of pharmacologic therapy have been reported to be beneficial in individual cases of dystonia; however, their role in treating dystonia has yet to be fully established.

In contrast, patients with focal dystonia tend to benefit most from treatment with botulinum toxin (BTX) injection. BTX is the treatment of choice for the majority of focal dystonias, including CD, and has been the most comprehensively investigated therapy for treatment of this patient group. Injections in the most severely affected muscle groups can also be employed in association with other treatments. BTX produces chemodenervation and local muscle paralysis by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. It also appears to improve reciprocal inhibition by altering sensory inflow through muscle afferent fibers.20 There are several serotypes of BTX produced by different species of Clostridium botulinum, although currently only types A and B are available for use in clinical practice. The duration of effect for BTX is variable but on average lasts 2 to 3 months. Lack of response to BTX injection may occur if there is long-standing disease with contractures, insufficient dosage, or the development of antibodies. Resistance associated with neutralizing antibodies occurs after repeated injections of BTX in 5% to 10% of cases.21

Both BTX A and BTX B have been shown to be efficacious in placebo-controlled trials,22,23 with improvements of 80% to 90% observed in patients with CD.24 Various injection strategies have been used to treat CD with BTX. Electromyograms (EMGs) may be useful adjuncts in some patients to guide selection of the appropriate muscle groups and determine the site of injection.25 However, there is debate as to whether EMG assessment and guidance provide superior results. It is usually a safe treatment that can be performed repeatedly, with no systemic side effects. Dysphagia due to local spreading of the toxin with injections of the sternocleidomastoid and pain at the injection site are the most commonly reported side effects. However, transient dizziness, dry mouth, flu-like symptoms, and dysphonia have also been reported.26

Surgery for Dystonic Conditions

More than two centuries after Minnius’s operation for torticollis, the Russian surgeon Buyalsky (1850) appears to have performed the first spinal accessory nerve section for spasmodic torticollis. He was followed by Morgan in 1867 and Collier in 1890.1 Spinal cord root section to treat spasmodic torticollis was first proposed more than a century ago by Keen (1891), who suggested unilateral section of the first three anterior cervical roots. This procedure of cervical rhizotomy was refined over the years by surgeons including Dandy, who in 1928 combined intradural section of the cervical sensory and motor roots, as well the accessory nerve bilaterally. Bertrand et al. have provided extensive data based on experience with a range of procedures for the relief of CD,27 including dorsal cervical rhizotomy derived from Keen’s operation. By 1979, variations of this procedure were still considered the operation of choice for CD refractory to medical therapy. However, long-term follow-up has disputed the effectiveness of these techniques.28 This issue of long-term efficacy, together with the high incidence of denervation-related complications, has led to the virtual abandonment of these procedures. Although satisfactory results have been reported for extensive muscle resections performed in patients with CD, the extreme nature of this surgery has prevented it from being widely deployed.29,30 Microvascular decompression of the accessory nerve, peripheral facial neurectomy, and cervical cord stimulation are further examples of procedures that have been used but fallen out of favor.

Deep Brain Stimulation for Dystonic Conditions

Development

The first traces in the history of deep brain stimulation (DBS) for treatment of dystonia are probably the historic animal experiments of Hess and Hassler in the early 1950s.30a Based on the kinematographic analysis of electric stimulation of various thalamic nuclei and basal ganglia structures, Hassler constructed an elaborate model to explain both the physiology and the pathophysiology of CD. In clinical practice, however, ablative thalamic surgery was used almost exclusively in the treatment of dystonia for decades, one of the greatest advocates being Cooper, who published the results of thalamotomies that he had performed on more than 200 patients over a 20-year period, with an average follow-up of 8 years.31 The reported results were very variable, with about 50% of patients benefiting from some postoperative amelioration. When Cooper in 197032 and Mundinger in 197733 reported their early results with thalamic DBS for generalized dystonia and CD, respectively, there was little interest in these studies, which remained almost completely unnoticed.

The globus pallidus internus (GPi) was suggested to be a suitable target for dystonia based on the experience that ablative pallidal surgery had a marked effect on contralateral dystonic dyskinesias in PD. Pallidotomy has been reported to be effective in various dystonic disorders34–37; however, it carries risks of speech and cognitive impairment and a partial recurrence of dystonic symptoms over time. Since its introduction, DBS has replaced ablative surgery for treatment of dystonia in many neurosurgical centers worldwide. Initial studies of DBS in dystonia targeted nuclei within the thalamus (Vim, Voa, and Vop) with variable outcome. GPi DBS, inspired initially by the success obtained with pallidotomy, is currently the most popular target for dystonia. Thalamic targets could be considered in patients with secondary dystonias resulting from pathologic changes in the pallidum or where GPi stimulation has been unsuccessful. More recently, subthalamic nucleus stimulation has been reported to be effective in focal and segmental dystonia.

Preoperative Assessment

Prior to consideration for surgery, all patients should be evaluated to assess the severity of dystonia and level of disability and to screen for secondary causes of dystonia. As well as a thorough neurologic assessment, a cognitive and psychiatric assessment is often undertaken to evaluate for cognition and mood disorders that may affect the outcome. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required to rule out any structural lesions in the basal ganglia that may interfere with surgical treatment. Preoperative MRI of the cervical spine may also be indicated to assess the contribution of degenerative cervical spine disease in CD.38

The Columbia rating scale,39 Tsui rating scale,40 and Jankovic rating scale41 are three systems specifically designed for the assessment of CD. These scales, however, have not been validated as extensively as the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS), a scoring system employing a video protocol, which has been used in many clinical reports.

Surgical Considerations and Techniques

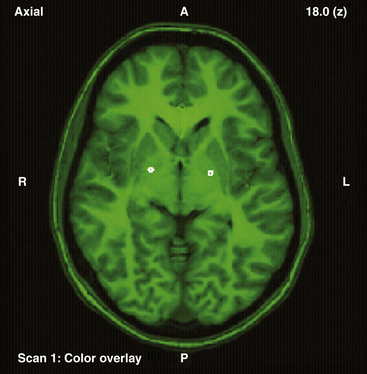

Our operative technique has been published elsewhere in more detail.42 Most patients with dystonic conditions have bilateral stimulation, and the two electrodes are usually implanted in the same surgical session under general anesthesia. Patients undergo stereotactic implantation of DBS electrodes into the posteroventral GPi using Image Fusion and Stereoplan43 to localize the targets by fusing the brain MRI to the stereotactic computed tomography (CT) scan44 (Fig. 115-1). These electrodes are then connected to a subcutaneous programmable pulse generator, usually implanted in the subclavicular tissue.

An alternative surgical method employs the use of microelectrode recordings; however, this is not routinely applied for stereotactic operations in our centers. Single-unit recordings with high-impedance electrodes can be helpful in evaluating the spatial morphology of the target and the trajectories to it. However, this advantage must be weighed against evidence that suggests microelectrode techniques may entail a higher complication rate, possibly because of the additional electrode “passes” through the brain required to make microelectrode recordings.45

Postoperative DBS Programming and Patient Management

The improvement of dystonia following pallidal stimulation may be delayed, and it can take several months before the full benefit is evident.46 The initial stimulation settings are based on a bipolar stimulation mode in accordance with the standard practice at our centers. This strategy differs from methods employed by other groups, which advocate monopolar electrode settings.47 Initial stimulator parameters aim for settings in the region of 2.0 to 4.0 V, 130 to 180 Hz, and 90 to 240 μs as tolerated by the individual patient, with progressive adjustment of electric parameters at each follow-up visit. Beneficial results have also been achieved with differing parameter settings, particularly with lower-frequency stimulation at 60 Hz.48,49 This did not appear to affect patient outcome when compared with a comparable group stimulated at a higher frequency. Furthermore, because of the lower energy of stimulation at 60 Hz, there appeared to be considerable benefit in terms of pulse generator longevity.

During the next few months, the intensity of stimulation is gradually increased. In general, only minimal adjustment is required later. Side effects of stimulation are reversible on adjustment of DBS settings. The threshold for undesired effects, such as perioral tightness, dysarthria, dizziness, paresthesia, and capsular responses, tends to shift during progressive adjustment of stimulation amplitude. Weight gain is observed in some patients, but this appears to be nonspecific and has been observed in pallidal surgery for other movement disorders.38

DBS has the advantages over lesional surgery of being reversible and adaptable. It avoids concern about the effects of lesioning on the developing brain in children and allows bilateral surgery to be undertaken more safely because of the reduced level of morbidity involved with DBS compared to lesions. However, DBS is not without its problems, which include hardware failure, high costs, and time-consuming follow-up, as well as those related to the perioperative period, such as infection and possible intracranial hemorrhage.42,45 The overall rate of hardware-related problems reported is very variable, ranging from 8% to 65%, and perhaps reflects differences in surgical technique.50,51

Failure of chronic GPi stimulation may result in a medical emergency, such as the rapid and potentially serious reappearance of dystonic symptoms that necessitate emergency admission following pulse generator battery depletion. This phenomenon, known as status dystonicus, has been described several times in the literature.52,53 However, in our groups’ experience, hardware failure caused by unilateral lead dysfunction usually results in a more gradual and progressive recurrence of symptoms, perhaps accounted for by the presence of the retained contralateral stimulation.

So far, most studies suggest that GPi DBS does not have a significant adverse effect on cognition or mood, although to date two suicides have been reported following GPi DBS for dystonia.54

Clinical Overview of GPi DBS for CD

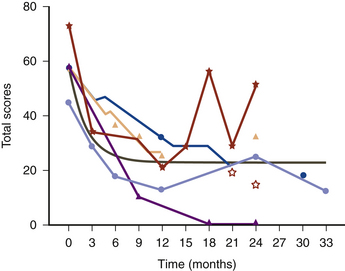

Since the first patients with CD were treated by GPi DBS in the late 1990s, beneficial results have been reported by a number of centers. Bilateral pallidal stimulation produces both symptomatic and functional improvement, including marked and sustained relief of pain in patients with CD.55 The gradual amelioration of CD over months was reflected in our data by improvement of a modified TWSTRS scale on subsequent follow-up examinations, and the mean scores were better at 1 year after surgery than at 3 months postoperatively (Fig. 115-2). In the patients from our centers, formal follow-up evaluation has demonstrated sustained improvements in the region of 60% to 65% in overall patient TWSTRS scores. In some patients, relief of pain preceded improvements observed in the other aspects of the TWSTRS scale. The literature also reports patients in whom relief of pain was the most prominent feature.56

A further benefit of GPi DBS in this patient group has been its use as an adjunct in patients with cervical dyskinesias and secondary cervical myelopathy prior to performing spinal surgery or spinal stabilization.57

Until recently, the majority of evidence supporting GPi DBS as an effective treatment in dystonic conditions was provided by pilot data comprising a number of case series or case reports. The evidence from these studies has been strengthened following the results of a number of trials detailing improvements in segmental, generalized58,59 CD.60 A number of studies with blinded outcome assessments have also been performed; these have further added to the evidence base.61–64 Verification of the continued benefit of this treatment has also been provided by recent long-term studies conveying the sustained improvements experienced by patients several years after their initial surgery.49,65–67

Age is generally not a contraindication to dystonia surgery, as patients from 8 to 75 years of age have been successfully operated on. While it is still debatable as to whether age at onset of dystonia influences outcome, the overall duration of dystonia has been reported to negatively correlate with poorer postoperative outcomes in a few studies.68 Thus, DBS should be considered earlier rather than later in the disease course to prevent secondary fixed deformity that may compromise rehabilitation.

Adler C.H. Strategies for controlling dystonia. Overview of therapies that may alleviate symptoms. Postgrad Med. 2000;108(5):151-152. 155-6, 159-60

Alterman R.L., Miravite J., Weisz D., et al. Sixty hertz pallidal deep brain stimulation for primary torsion dystonia. Neurology. 2007;69(7):681-688.

Cersosimo M.G., Raina G.B., Piedimonte F., et al. Pallidal surgery for the treatment of primary generalized dystonia: long-term follow-up. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110(2):145-150.

Comella C.L., Jankovic J., Brin M.F. Use of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurology. 2000;55(12 Suppl 5):S15-S21.

Cooper I.S. 20-year followup study of the neurosurgical treatment of dystonia musculorum deformans. Adv Neurol. 1976;14:423-452.

Coubes P., Roubertie A., Vayssiere N., et al. Treatment of DYT1-generalised dystonia by stimulation of the internal globus pallidus. Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2220-2221.

de Carvalho Aguiar P.M., Ozelius L.J. Classification and genetics of dystonia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(5):316-325.

Hung S.W., Hamani C., Lozano A.M., et al. Long-term outcome of bilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation for primary cervical dystonia. Neurology. 2007;68(6):457-459.

Isaias I.U., Alterman R.L., Tagliati M. Deep brain stimulation for primary generalized dystonia: long-term outcomes. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(4):465-470.

Isaias I.U., Alterman R.L., Tagliati M. Outcome predictors of pallidal stimulation in patients with primary dystonia: the role of disease duration. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 7):1895-1902.

Jankovic J. Medical therapy and botulinum toxin in dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:169-183.

Jankovic J., Tsui J., Bergeron C. Prevalence of cervical dystonia and spasmodic torticollis in the United States general population. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(7):411-416.

Kiss Z.H., Doig-Beyaert K., Eliasziw M., et al. The Canadian multicentre study of deep brain stimulation for cervical dystonia. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 11):2879-2886.

Krauss J.K., Yianni J., Loher T.J., et al. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;21(1):18-30.

Kupsch A., Benecke R., Muller J., et al. Pallidal deep-brain stimulation in primary generalized or segmental dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1978-1990.

Loher T.J., Capelle H.H., Kaelin-Lang A., et al. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia: outcome at long-term follow-up. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):881-884.

Marsden C.D., Obeso J.A., Zarranz J.J., et al. The anatomical basis of symptomatic hemidystonia. Brain. 1985;108(Pt 2):463-483.

Meares R. Natural history of spasmodic torticollis, and effect of surgery. Lancet. 1971;2(7716):149-150.

Morgan J.C., Sethi K.D. A single-blind trial of bilateral globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation in medically refractory cervical dystonia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(4):279-280.

Mueller J., Skogseid I.M., Benecke R., et al. Pallidal deep brain stimulation improves quality of life in segmental and generalized dystonia: results from a prospective, randomized sham-controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2008;23(1):131-134.

Papanastassiou V., Rowe J., Scott R., et al. Use of the Radionics Image Fusion™ and Stereoplan™ programs for target localisation in functional neurosurgery. J Clin Neurosci. 1998;5(1):28-32.

Pretto T.E., Dalvi A., Kang U.J., et al. A prospective blinded evaluation of deep brain stimulation for the treatment of secondary dystonia and primary torticollis syndromes. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):405-409.

Rowe J.G., Davies L.E., Scott R., et al. Surgical complications of functional neurosurgery treating movement disorders: results with anatomical localisation. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6(1):36-37.

Vidailhet M., Vercueil L., Houeto J.L., et al. Bilateral, pallidal, deep-brain stimulation in primary generalised dystonia: a prospective 3 year follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):223-229.

Yianni J., Bain P.G., Gregory R.P., et al. Post-operative progress of dystonia patients following globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(3):239-247.

1. Kandel E.I., Watts G., Walker A.E. Functional and stereotactic neurosurgery. Plenum Medical. 1989.

2. Goetz C.G., Chmura T.A., Lanska D.J. History of dystonia: part 4 of the MDS-sponsored history of movement disorders exhibit, Barcelona, June, 2000. Mov Disord. 2001;16(2):339-345.

3. Marsden C.D., Obeso J.A., Zarranz J.J., et al. The anatomical basis of symptomatic hemidystonia. Brain. 1985;108(Pt 2):463-483.

4. Fahn S., Greene P., Ford B., et al. Handbook of Movement Disorders. Current Medicine Inc. 1998.

5. Nutt J.G., Muenter M.D., Aronson A., et al. Epidemiology of focal and generalized dystonia in Rochester, Minnesota. Mov Disord. 1988;3(3):188-194.

6. Dobyns W.B., Ozelius L.J., Kramer P.L., et al. Rapid-onset dystonia–parkinsonism. Neurology. 1993;43(12):2596-2602.

7. Jankovic J., Tsui J., Bergeron C. Prevalence of cervical dystonia and spasmodic torticollis in the United States general population. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(7):411-416.

8. Kamm C. [Genetics of dystonia]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2009;77(Suppl 1):S32-S36.

9. de Carvalho Aguiar P.M., Ozelius L.J. Classification and genetics of dystonia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(5):316-325.

10. Defazio G., Livrea P., Guanti G., et al. Genetic contribution to idiopathic adult-onset blepharospasm and cranial-cervical dystonia. Eur Neurol. 1993;33(5):345-350.

11. Stojanovic M., Cvetkovic D., Kostic V.S. A genetic study of idiopathic focal dystonias. J Neurol. 1995;242(8):508-511.

12. Burton K., Farrell K., Li D., et al. Lesions of the putamen and dystonia: CT and magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1984;34(7):962-965.

13. Langlois M., Richer F., Chouinard S. New perspectives on dystonia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2003;30(Suppl 1):S34-S44.

14. Friedman J., Standaert D.G. Dystonia and its disorders. Neurol Clin. 2001;19(3):681-705. vii

15. Jankovic J. Medical therapy and botulinum toxin in dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:169-183.

16. Bressman S.B., Greene P.E. Dystonia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(3):275-285.

17. Greene P. Baclofen in the treatment of dystonia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1992;15(4):276-288.

18. Das S.K., Choudhary S.S. A spectrum of dystonias—clinical features and update on management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(6):622-630.

19. Thiel A., Dressler D., Kistel C., et al. Clozapine treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Neurology. 1994;44(5):957-958.

20. Priori A., Berardelli A., Mercuri B., et al. Physiological effects produced by botulinum toxin treatment of upper limb dystonia. Changes in reciprocal inhibition between forearm muscles. Brain. 1995;118(Pt 3):801-807.

21. Hanna P.A., Jankovic J. Mouse bioassay versus Western blot assay for botulinum toxin antibodies: correlation with clinical response. Neurology. 1998;50(6):1624-1629.

22. Comella C.L., Jankovic J., Brin M.F. Use of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurology. 2000;55(12 Suppl 5):S15-S21.

23. Sycha T., Kranz G., Auff E., et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of rare head and neck pain syndromes: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurol. 2004;251(Suppl 1):I19-I30.

24. Adler C.H. Strategies for controlling dystonia. Overview of therapies that may alleviate symptoms. Postgrad Med. 2000;108(5):151-152. 155-6, 159-60

25. Childers M.K. The importance of electromyographic guidance and electrical stimulation for injection of botulinum toxin. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14(4):781-792.

26. Dauer W.T., Burke R.E., Greene P., et al. Current concepts on the clinical features, aetiology and management of idiopathic cervical dystonia. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):547-560.

27. Bertrand C., Molina-Negro P., Martinez S.N. Combined stereotactic and peripheral surgical approach for spasmodic torticollis. Appl Neurophysiol. 1978;41(1-4):122-133.

28. Meares R. Natural history of spasmodic torticollis, and effect of surgery. Lancet. 1971;2(7716):149-150.

29. Chen X.K., Ji S.X., Zhu G.H., et al. Operative treatment of bilateral retrocollis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113(3-4):180-183.

30. Xinkang C. Selective resection and denervation of cervical muscles in the treatment of spasmodic torticollis: results in 60 cases. Neurosurgery. 1981;8(6):680-688.

30a. Hassler R., Hess W.R. [Experimental and anatomical findings in rotatory movements and their nervous apparatus]. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. 1954;192(5):488-526.

31. Cooper I.S. 20-year followup study of the neurosurgical treatment of dystonia musculorum deformans. Adv Neurol. 1976;14:423-452.

32. Cooper I.S. Neurosurgical treatment of dystonia. Neurology. 1970;20(11):133-148.

33. Mundinger F. [New stereotactic treatment of spasmodic torticollis with a brain stimulation system (author’s transl)]. Med Klin. 1977;72(46):1982-1986.

34. Iacono R.P., Kuniyoshi S.M., Schoonenberg T. Experience with stereotactics for dystonia: case examples. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:221-226.

35. Lozano A.M., Kumar R., Gross R.E., et al. Globus pallidus internus pallidotomy for generalized dystonia. Mov Disord. 1997;12(6):865-870.

36. Ondo W.G., Desaloms J.M., Jankovic J., et al. Pallidotomy for generalized dystonia. Mov Disord. 1998;13(4):693-698.

37. Yoshor D., Hamilton W.J., Ondo W., et al. Comparison of thalamotomy and pallidotomy for the treatment of dystonia. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(4):818-824. discussion 824-6

38. Krauss J.K., Yianni J., Loher T.J., et al. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;21(1):18-30.

39. Greene P., Kang U., Fahn S., et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Neurology. 1990;40(8):1213-1218.

40. Tsui J.K., Eisen A., Stoessl A.J., et al. Double-blind study of botulinum toxin in spasmodic torticollis. Lancet. 1986;2(8501):245-247.

41. Jankovic J. Treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders with tetrabenazine: a double-blind crossover study. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(1):41-47.

42. Joint C., Nandi D., Parkin S., et al. Hardware-related problems of deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S175-S180.

43. Papanastassiou V., Rowe J., Scott R., et al. Use of the Radionics Image Fusion™ and Stereoplan™ programs for target localisation in functional neurosurgery. J Clin Neurosci. 1998;5(1):28-32.

44. Orth R.C., Sinha P., Madsen E.L., et al. Development of a unique phantom to assess the geometric accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for stereotactic localization. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(6):1423-1429. discussion 1429-31

45. Rowe J.G., Davies L.E., Scott R., et al. Surgical complications of functional neurosurgery treating movement disorders: results with anatomical localisation. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6(1):36-37.

46. Yianni J., Bain P.G., Gregory R.P., et al. Post-operative progress of dystonia patients following globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(3):239-247.

47. Coubes P., Roubertie A., Vayssiere N., et al. Treatment of DYT1-generalised dystonia by stimulation of the internal globus pallidus. Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2220-2221.

48. Alterman R.L., Miravite J., Weisz D., et al. Sixty hertz pallidal deep brain stimulation for primary torsion dystonia. Neurology. 2007;69(7):681-688.

49. Isaias I.U., Alterman R.L., Tagliati M. Deep brain stimulation for primary generalized dystonia: long-term outcomes. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(4):465-470.

50. Lyons K.E., Koller W.C., Wilkinson S.B., et al. Surgical and device-related events with deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2001. 56(April): A147 (Suppl)

51. Hariz M.I. Complications of deep brain stimulation surgery. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S162-S166.

52. Manji H., Howard R.S., Miller D.H., et al. Status dystonicus: the syndrome and its management. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 2):243-252.

53. Teive H.A., Munhoz R.P., Souza M.M., et al. Status dystonicus: study of five cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63(1):26-29.

54. Foncke E.M., Schuurman P.R., Speelman J.D. Suicide after deep brain stimulation of the internal globus pallidus for dystonia. Neurology. 2006;66(1):142-143.

55. Krauss J.K., Pohle T., Weber S., et al. Bilateral stimulation of globus pallidus internus for treatment of cervical dystonia. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):837-838.

56. Kulisevsky J., Lleo A., Gironell A., et al. Bilateral pallidal stimulation for cervical dystonia: dissociated pain and motor improvement. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1754-1755.

57. Krauss J.K., Loher T.J., Pohle T., et al. Pallidal deep brain stimulation in patients with cervical dystonia and severe cervical dyskinesias with cervical myelopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(2):249-256.

58. Kupsch A., Benecke R., Muller J., et al. Pallidal deep-brain stimulation in primary generalized or segmental dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1978-1990.

59. Mueller J., Skogseid I.M., Benecke R., et al. Pallidal deep brain stimulation improves quality of life in segmental and generalized dystonia: results from a prospective, randomized sham-controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2008;23(1):131-134.

60. Morgan J.C., Sethi K.D. A single-blind trial of bilateral globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation in medically refractory cervical dystonia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(4):279-280.

61. Pretto T.E., Dalvi A., Kang U.J., et al. A prospective blinded evaluation of deep brain stimulation for the treatment of secondary dystonia and primary torticollis syndromes. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):405-409.

62. Kiss Z.H., Doig-Beyaert K., Eliasziw M., et al. The Canadian multicentre study of deep brain stimulation for cervical dystonia. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 11):2879-2886.

63. Vidailhet M., Vercueil L., Houeto J.L., et al. Bilateral, pallidal, deep-brain stimulation in primary generalised dystonia: a prospective 3 year follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):223-229.

64. Diamond A., Shahed J., Azher S., et al. Globus pallidus deep brain stimulation in dystonia. Mov Disord. 2006;21(5):692-695.

65. Loher T.J., Capelle H.H., Kaelin-Lang A., et al. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia: outcome at long-term follow-up. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):881-884.

66. Cersosimo M.G., Raina G.B., Piedimonte F., et al. Pallidal surgery for the treatment of primary generalized dystonia: long-term follow-up. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110(2):145-150.

67. Hung S.W., Hamani C., Lozano A.M., et al. Long-term outcome of bilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation for primary cervical dystonia. Neurology. 2007;68(6):457-459.

68. Isaias I.U., Alterman R.L., Tagliati M. Outcome predictors of pallidal stimulation in patients with primary dystonia: the role of disease duration. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 7):1895-1902.