56 Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

When venous drainage of the brain is compromised, arterial flow creates back-pressure into tissue capillaries causing capillary congestion, interstitial edema, decreased tissue perfusion, and ultimately ischemia. Eventually capillary rupture causes hematoma formation. This process of cerebral venous congestion followed by infarction (not conforming to strict arterial territories) and hemorrhage is the hallmark of cerebral sinus thrombosis. The causes of cerebral venous thrombosis vary (Box 56-1), but many relate to transient or permanent hypercoagulable states, with dehydration acting as a common precipitating event. A thorough investigation for such etiologies is crucial to directing long-term treatment and anticipating potential comorbidities.

Anatomy

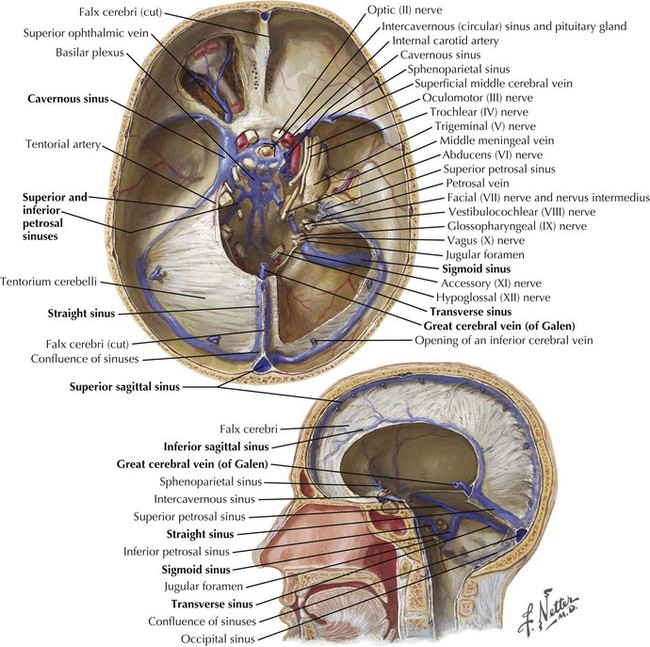

The dura is formed of two layers, one abutting the inner calvarium and the other forming the outer meningeal covering. These layers separate in the midsagittal and transverse planes, forming dural venous sinuses ultimately draining into the jugular veins. A single superior sagittal sinus joins the often asymmetric but paired transverse sinus at the confluence of sinuses or torcular herophili (Fig. 56-1). The transverse sinuses run laterally from the occipital bone to the middle cerebral fossa along the tentorium cerebelli. The right is often larger and is continuous with the superior sagittal sinus whereas the left curves out laterally as an extension of the single midline straight sinus. The straight sinus runs downward from near the splenium of the corpus callosum to the occipital protuberance. The sigmoid sinus curves down toward the skull base from the transverse sinus and joins the inferior petrosal sinus at the jugular foramen to form the jugular vein.

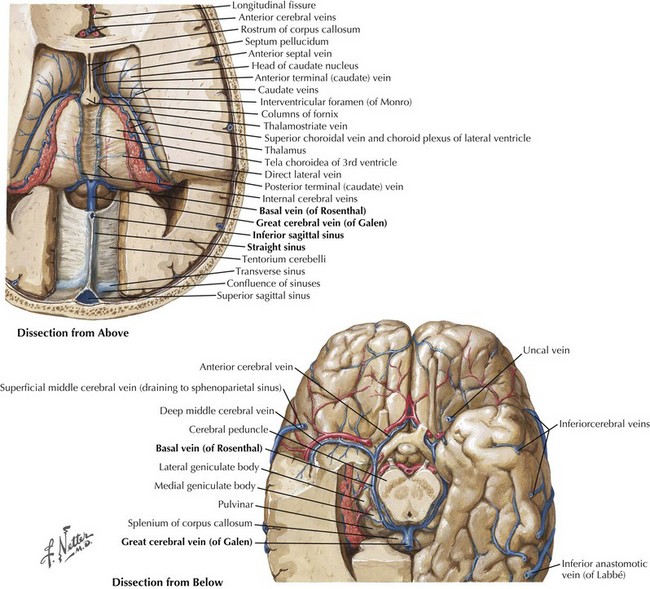

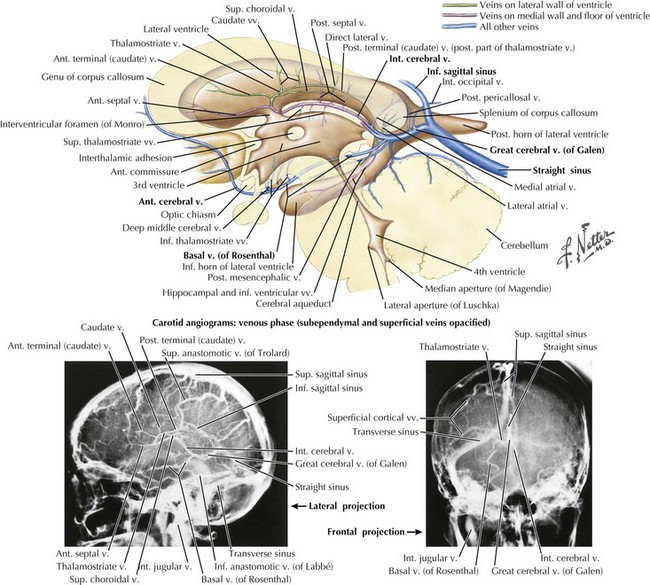

The straight sinus (Figs. 56-1 through 56-4) is formed by the splayed falx layered over the cerebellar tentorium. The inferior sagittal sinus runs in the fold of the lower arch of the falx cerebri and joins the cerebral vein of Galen in the proximity of the posterior horns of the lateral ventricles to form the straight sinus. The superior and inferior sagittal sinuses provide drainage for the cerebral hemispheres.

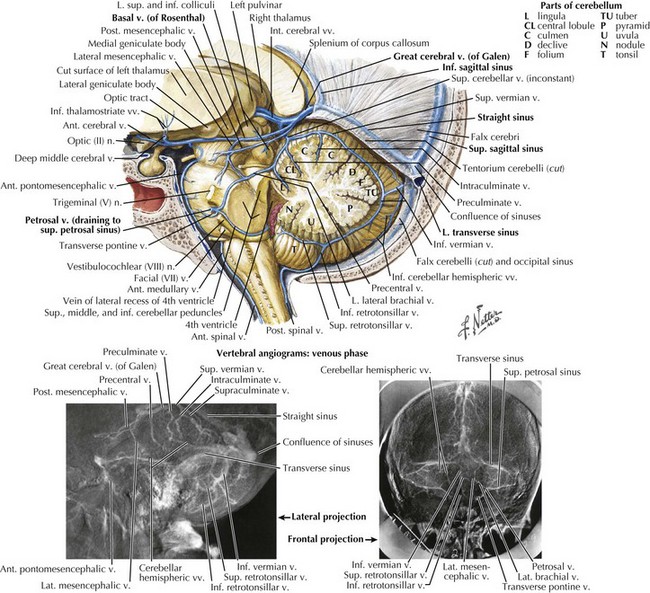

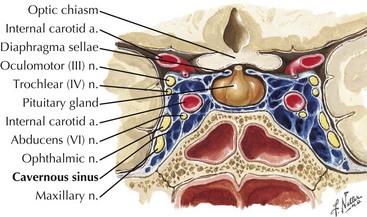

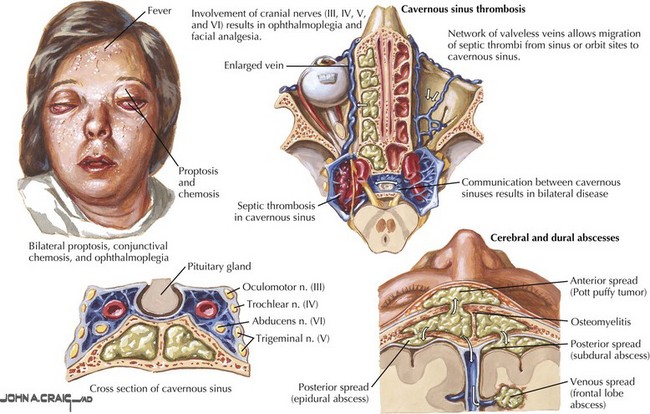

The cavernous sinus runs posteriorly at the brain base from the sphenoid bone in the area of the superior orbital fissure to the petrous temporal bone. Cavernous sinus tributaries include cerebral veins and the ophthalmic vein. The cavernous sinus drains along the medial upper layer of the tentorium and through the superior petrosal sinus, coursing posteriorly to the transverse sinus. The cavernous sinus houses the carotid artery; the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves; and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 56-5). A mesh of venous sinuses around the pituitary and the anterior skull base connects the two cavernous sinuses across the midline. The superior petrosal sinus drains the anterior brainstem and the anterior superior and inferior cerebellar hemispheres. Below the tentorium, along the skull base, the inferior petrosal sinus links the cavernous sinus to the sigmoid sinus (Fig. 56-1).

Clinical Presentation

Specific Clinical Presentations

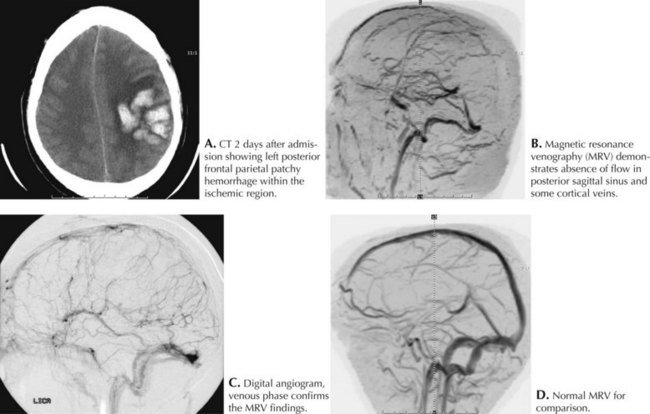

Intracerebral cortically based hemorrhages, common with SSST, are often associated with focal neurologic signs and seizures. Confusion, behavioral changes, somnolence, and coma may occur as thrombosis propagates within the sinus and ICP increases. These signs usually develop after the clot extends into the posterior third of the sinus. In most cases of SSSTs, one of the lateral sinuses is concomitantly involved (Fig. 56-6).

Base of the skull sinus thrombosis has a clinical presentation of painful cranial neuropathies. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is often septic from facial, orbital, or middle ear infections with eye pain, proptosis, and chemosis as frequent features (Fig. 56-7). Varying degrees of ophthalmoplegia are present secondary to involvement of CN-III, -IV, and -VI running through the lateral portion of the cavernous sinus. The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) also courses through this sinus, and forehead sensory changes are occasionally seen. Inferior petrosal sinus thrombosis, often septic, causes retro-orbital pain, trigeminal V1 sensory changes, and abducens nerve palsy (Gradenigo syndrome; CN-V, -VI). Localized thrombosis involving the internal jugular vein may be an extension of transverse or sigmoid sinus thrombosis or may result from catheterization or trauma. This often presents with CN-IX, -X, and -XI dysfunction (jugular foramen or Vernet syndrome).

Diagnostic Approach

MRI and MRV have largely replaced angiography as standard imaging techniques to confirm cerebral sinus thrombosis (see Fig. 56-6). Cerebral angiography with a prolonged venous phase is now reserved for cases not clearly diagnosed by MRI or CT and for patients requiring intrasinus thrombolysis.

Baker MD, Opatowsky MJ, Wilson JA, et al. Rheolytic catheter and thrombolysis of dural venous sinus thrombosis: a case series. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:487-494.

De Bruijn SF, De Haan RJ, Stam J. Clinical features and prognostic factors of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a prospective series of 59 patients. For The Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Study Group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:105-108.

DeBruijn SF, Stam J. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of anticoagulation treatment with low molecular weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30:481-482. Of those treated with nadroparin 13% had a bad outcome compared to 21% in the placebo group. There were no new symptomatic intracranial hemorrhagic complications even though many patients in the treatment group initially presented with ICH

Einhaupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338:597-600. Randomized controlled study terminated after 20 patients because of a significant advantage in favor of heparin over placebo in angiographically proven cases of cerebral venous thrombosis

Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, et al. ISCVT Investigators. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT) Stroke. 2004 Mar;35(3):664-670. Large multinational prospective observational study that shows good recovery in 79% of patients. A subgroup of men with venous hematomas, low Glasgow coma scores, deep venous involvement and malignancy tended to do worse

Ferro JM, Lopes MB, Rosas MJ, et al. Long-term prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the VENOPORT study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:272-278.

Haley EC, Brasmear HR, Barth JT, et al. Deep cerebral venous thrombosis: clinical, neuroradiological and neuropsychological correlates. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:337-340.

Horton JC, Seiff SR, Pitts LH, et al. Decompression of the optic nerve sheath for vision-threatening papilledema caused by dural sinus occlusion. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:203-212.

Mehraein S, Schmidtke K, Villringer A, et al. Heparin treatment in cerebral sinus and venous thrombosis: patients at risk of fatal outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:17-21.

Preter M, Tzourio C, Ameri A, et al. Long-term prognosis in cerebral venous thrombosis: follow-up of 77 patients. Stroke. 1996;27:243-246.

Wasay M, Bakshi R, Kojan S, et al. Nonrandomized comparison of local urokinase thrombolysis versus systemic heparin anticoagulation for superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2001;32:2310-2317.