Caustics

Perspective

Caustic or corrosive agents have the potential to cause tissue injury on contact with mucosal surfaces. Agents capable of causing chemical injury include alkaline and acidic corrosives. Alkalis accept protons, resulting in the formation of conjugate acids and free hydroxide ions. Lye is an example of an alkali caustic and refers to both sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH). Ammonia (NH3) is another common alkaline corrosive. Acids are proton donors, as they dissociate into conjugate bases and free hydrogen ions in solution. Acidic caustics include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). The injury from caustic agents typically increases with a pH below 3 or above 11. Other chemicals that have caustic properties include phenol, formaldehyde, iodine, and concentrated hydrogen peroxide. This chapter discusses oral exposure. Dermal and inhalational exposures are discussed in Chapter 64 and Chapter 159, respectively.

Most caustic exposures are intentional for the purpose of self-harm. About 75% of reported caustic ingestions are intentional.1 Accidental ingestions occur typically among the pediatric and elderly populations. Transfer and storage of cleaners in alternative containers that may not be “child proof,” such as soda bottles and jars, contribute to unintentional ingestion. Intentional ingestions may have a greater degree of oropharyngeal sparing because of rapid swallowing but have a higher likelihood of serious injury.2 More than half of suicidal patients who ingest caustic agents have a history of psychiatric illness.

Before 1950, strong lye with concentrations greater than 50% made up a major portion of caustic ingestions in the United States, leading to poor outcomes. To control the frequency of caustic ingestions especially in children, the Federal Caustic Act was passed in 1927, followed by the Federal Hazardous Substance Labeling Act of 1960 and the Safe Packaging Act of 1970.3 Still, more than 40,000 exposures involving caustic agents occur in the United States every year.1

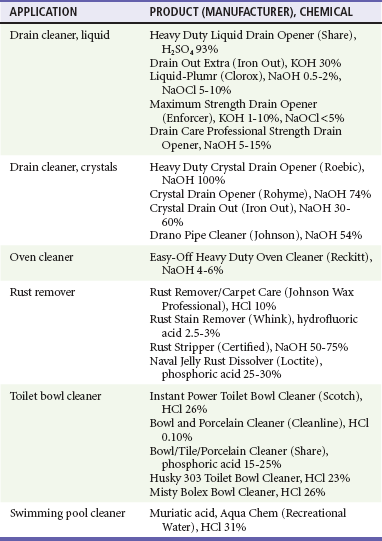

Some household products, such as liquid drain cleaners, continue to have high concentrations of alkali (30% KOH) or acid (93% H2SO4) (Table 153-1). These products often do not have concentration or content information available on the label, making it difficult for physicians to determine the severity of exposure.4 Commercial industries, farms (dairy pipeline cleaners containing liquid NaOH and KOH in concentrations of 8-25%), and swimming pool chemicals also contain caustics in high concentrations.

The alkali powder in air bags can cause ocular burns. Perfume accidentally sprayed into the eyes can be caustic. Cement is alkaline and causes topical burns, typically on the knees.5 Although hair relaxer creams contain NaOH and have a pH of 11.2 to 11.9, injuries after ingestion are usually limited.3

Caustic ingestions may occur when methamphetamine is produced from over-the-counter medications and household chemicals. Sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, NaOH, ammonium hydroxide, anhydrous ammonia, and metallic lithium are all used in the clandestine production of methamphetamine.6 Severe caustic injuries in these situations can cause stricture formation, esophageal resection, and the need for colonic interposition.

More than 70 different pills can cause damage when they come in contact with esophageal mucus for prolonged periods. Patients who take medications in the supine position or who take pills without water are at higher risk. Pills most likely to adhere are doxycycline, tetracycline, potassium chloride, and aspirin. Potassium chloride is particularly dangerous and has caused perforation into the aorta, left atrium, and bronchial artery.7

Principles

Factors that influence the extent of injury from a caustic exposure include type of agent, concentration of solution, volume, viscosity, duration of contact, pH, and presence or absence of food in the stomach. The titratable alkaline reserve of an alkali or acid correlates with the ability to produce tissue damage. Concentrated forms of acids and bases generate heat, resulting in superimposed thermal injury.8

Acidic compounds desiccate epithelial cells and cause coagulation necrosis. An eschar is formed that limits further penetration. Because acids tend to have a strong odor and cause immediate pain on contact, the quantity ingested is usually limited. Because of resistance of squamous epithelium to coagulation necrosis, acids are thought to be less likely to cause esophageal and pharyngeal injury,9 although severe esophageal and laryngeal burns still occur. Acids can be absorbed systemically, causing metabolic acidosis as well as damage to the spleen, liver, biliary tract, pancreas, and kidneys from perforation and direct local contact.

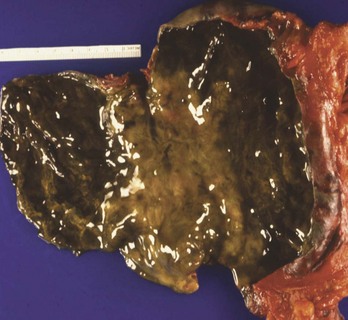

Alkaline contact causes liquefaction necrosis, fat saponification, and protein disruption, allowing further penetrance of the alkaline substance into the tissue. The depth of the necrosis depends on the concentration of the lye. A concentration of 30% NaOH in contact with tissue for 1 second results in a full-thickness burn. Alkalis are colorless and odorless, and unlike acids, they do not cause immediate pain on contact. Alkaline ingestions typically involve the squamous epithelial cells of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, and esophagus. The narrow portions of the esophagus, where pooling of secretions can occur, are also commonly involved. Alkalis may also cause gastric necrosis (Figs. 153-1 and 153-2), intestinal necrosis, and perforation. The esophagus can also be injured (Fig. 153-3). Burns below the pylorus carry a 50% mortality compared with 9% for burns above the pylorus.10

Caustic injury is categorized as first, second, and third degree, similar to a thermal burn, by appearance on endoscopy. The initial depth of injury found on esophagoscopy correlates with the risk of stricture formation. First-degree burns (also known as grade 1) consist of edema and hyperemia. Second-degree burns (grade 2) can be further divided into 2a, which are noncircumferential, and 2b, which are nearly circumferential. Overall, second-degree burns are characterized by superficial ulcers, whitish membranes, exudates, friability, and hemorrhage. Third-degree burns (grade 3) are associated with transmural involvement with deep injury, necrotic mucosa, or frank perforation of the stomach or esophagus. Although grade 1 injuries do not progress to stricture, 15 to 30% of all grade 2 burns and up to 75% of circumferential grade 2 injuries of the esophagus develop strictures. With full-thickness third-degree burns (grade 3), up to 90% result in stricture; however, the formation of strictures is decreasing for both second- and third-degree burns, possibly because of the type and caustic intensity of the substance ingested.11 Whether heat from the exothermic reaction increases the injury has never been quantified, but it has led to concerns about initial dilution or gastric lavage.12

Clinical Features

Airway edema and esophageal and gastric perforation are the most emergent issues. Laryngeal edema occurs in a matter of minutes to hours. Systemic toxicity, hypovolemic shock, and hemodynamic instability with hypotension, tachycardia, fever, and acidosis are ominous findings. Small ingestions of potent substances can be as serious as larger ingestions. More than 40% of patients reporting to have “only taken a lick” have esophageal burns.13 Patients present with oral pain (41%), abdominal pain (34%), vomiting (19%), and drooling (19%).14 Patients can have wheezing and coughing, stridor, and dysphonia. Chest pain is common. Visible burns to the face, lips, and oral cavity may be seen (Fig. 153-4). Skin burns can occur from spillage or secondary contamination after vomiting. Peritoneal signs suggest hollow viscus perforation or contiguous extension of the burn injury to adjoining visceral areas. Tracheal necrosis is one of the most frequent causes of death after caustic ingestion.15

Figure 153-4 Lip burn after exposure to 35% potassium hydroxide.

Studies present conflicting data correlating clinical symptoms with the severity of esophageal burns.14 Oropharyngeal burns alone do not appear predictive of more distal injury, but prolonged drooling and dysphagia predict significant lesions with 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity.15 Vomiting and stridor also suggest burn injury.

Patients have an increase in esophageal cancer (1000-fold to 3000-fold increases) that develops 40 to 50 years after the caustic ingestion. Long term, 1.8% of patients who ingest caustic soda have esophageal cancer,16 and nearly 3% of esophageal cancer patients have a history of caustic ingestion.

Significant acid ingestions may be devastating and result in a higher mortality rate than alkali ingestions. The fulminant course of some acid ingestions may be due to systemic absorption of the acid, resulting in metabolic acidosis (which may also be the result of extensive tissue necrosis), hemolysis, and renal failure. Ingestion of glacial acetic acid (80% acetic acid) is common among certain ethnic populations as a suicidal gesture or accidental ingestion during food preparation, resulting in systemic complications, including renal and hepatic insufficiency, hemolysis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.17 Ingestion of sulfuric and hydrochloric acid typically does not cause these systemic complications.18

Diagnostic Strategies

Patients with chest and abdominal pain should have a chest radiograph and decubitus or upright abdominal studies to look for peritoneal and mediastinal air, denoting perforation or pleural effusion, and suggestion of abdominal involvement should prompt abdominal computed tomography or ultrasonography. In the suicidal patient, the physical examination and chest radiograph do not “rule out” pneumoperitoneum. Radiographs have low negative predictive values for detection of free air.10

Hydrofluoric acid exposures, whether by inhalation, ingestion, or dermal contact (hand size or larger), are notorious for the effect of absorbed fluoride and require immediate cardiac monitoring to assess for QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes, or other ventricular dysrhythmias. Rapid cardiac deterioration can occur in these unusual cases.19 Serum calcium and magnesium levels should also be determined.

The depth of burns cannot be predicted on the basis of signs or symptoms. Noninvasive techniques (barium swallow) do not gauge the depth of burn injury. Patients with signs and symptoms (vomiting, drooling, stridor, or dyspnea) of intentional ingestion should undergo endoscopy within 12 to 24 hours to define the extent of the disease, but endoscopy is contraindicated in patients with possible or known perforation. Endoscopy performed too early may miss the extent or depth of tissue injury. Wound softening in the subacute phase when the likelihood of perforation is greatest makes late endoscopy (after 24 hours) more hazardous. Flexible endoscopy is safer than the older rigid instruments, with fewer perforation complications. However, the endoscopy should terminate at the level of the most proximal circumferential burn.20 A soft feeding tube or silk string can be placed in the esophagus, when burns are present, for future dilation.

Management

In the acute phase, barium swallow is of little use because it delays and obscures endoscopy and does not reveal first- or second-degree mucosal burns.21 Thoracoabdominal computed tomography can be useful in assessing the degree of esophageal damage after caustic ingestions.22

Different treatment modalities in stricture prevention have been discussed, including antibiotics, corticosteroids, total parenteral nutrition, nasogastric tube, and antacids, but none has been proved to be effective, and optimal management remains controversial.23,24 Although the use of systemic corticosteroids has been recommended in the past, it has not statistically significantly decreased stricture after grade 2 esophageal burns.25 Moreover, steroid therapy in grade 2 and grade 3 burns includes the risk for brain abscess, hemorrhage, pneumonia, severe esophagogastric necrosis, osteoporosis, and prepyloric ulcer formation.26 Steroids can also mask early signs of inflammation and inhibit resistance to infection. Prophylactic antibiotics may potentially mask evidence of impending perforation.

Special Cases

Ocular alkali exposures are true ophthalmologic emergencies. Immediate and aggressive lavage with at least 2 L of normal saline per eye is indicated in almost all cases except frank perforation. Management is described in Chapter 71.

Dermal caustic exposures can also result in significant burn injuries (see Chapter 64). Clothing removal, copious irrigation, and local wound débridement are the most important initial treatment measures. Hydrofluoric acid burns warrant special attention. Although this is a relatively weak acid compared with HCl or H2SO4, the dissociated fluoride anion is a problem because of its extreme electronegativity. Deaths from hydrofluoric acid exposure have occurred after ingestion; after skin contact in areas as small as 1% of the body surface area, the size of the palm of the hand, with concentrated hydrofluoric acid; and after inhalation of hydrofluoric acid vapor.27 Systemic toxicity is characterized by profound hypocalcemia and dysrhythmias; cardiac monitoring and serum calcium and magnesium monitoring are warranted in all but the most limited fingertip exposures.28 Sudden fatal deterioration can occur despite an initially normal serum calcium level, but oral treatment of hydrofluoric acid ingestion with CaCl2 and MgSO4 has not increased survival.29 Empirical intervention with high-dose intravenous calcium chloride or magnesium sulfate should be administered for QTc prolongation and life-threatening dysrhythmias and with serum hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. Further management is discussed in Chapter 64.

Button (disk) batteries and conventional alkaline cylindrical batteries pose potential obstructive and chemical hazards if they are ingested. Ingestion of large 25-mm wafer-sized button batteries was a common problem in the past, but the smaller button batteries of today are less likely to cause esophageal obstruction. Button batteries are usually made of a metallic salt (lithium, mercury, nickel, zinc, cadmium, or silver) bathed in NaOH or KOH. Obstruction can cause pressure necrosis, caustic injury due to leakage of alkaline medium, or electrical injury. Ulceration, perforation, and possible fistula formation occur but are uncommon. Heavy-metal toxicity in this setting has not been reported.30

Evaluation of button battery ingestions includes radiography to assess the position of the foreign body. Batteries lodged in the airway or esophagus require expeditious removal. Gastric or intestinal batteries can be treated with watchful waiting.30 Checking the stool for passage of the batteries is recommended. Follow-up radiographs should be obtained in 1 week if the battery has not passed.

References

1. Bronstein, AC, et al. 2009 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:979.

2. Kay, M, Wyllie, R. Caustic ingestion and the role of endoscopy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:8.

3. Aronow, SP, et al. Hair relaxers: A benign caustic ingestion? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:120.

4. Baskm, D, et al. A standardised protocol for the acute management of corrosive ingestion in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:824.

5. Spoo, J, Elsner, P. Cement burns: A review 1960-2000. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:68.

6. Farst, K, et al. Methamphetamine exposure presenting as caustic ingestions in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:341.

7. John, SK, et al. Life-threatening hyperkalemia from nutritional supplements: Uncommon or undiagnosed? Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:1237.

8. Bertinelli, A, et al. Serious injuries from dishwasher powder ingestions in small children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:129.

9. Cordero, B, Savage, R. Corrosive ingestions. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:154.

10. Palmer, M, et al. A, B, Cs of caustic ingestions in suicidal adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:246.

11. Bicakci, U, et al. Minimally invasive management of children with caustic ingestion: Less pain for patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:251.

12. Homan, CS, et al. Thermal characteristics of neutralization therapy and water dilution for strong acid ingestion: An in-vivo canine model. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:286.

13. Andreoni, B, et al. Esophageal perforation and caustic injury: Emergency management of caustic ingestion. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10:95.

14. Gorman, RL, et al. Initial symptoms as predictors of esophageal injury in alkaline corrosive ingestions. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:189.

15. Nuutinen, M, et al. Consequences of caustic ingestions in children. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:1200.

16. Mamede, RC, de Mello-Filho, FV. Ingestion of caustic substances and its complications. Sao Paulo Med J. 2001;119:10.

17. Kim, SJ, et al. CT imaging of gastric and hepatic complications after ingestion of glacial acetic acid. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:564.

18. Poley, J, et al. Ingestion of acid and alkaline agents: Outcome and prognostic value of early upper endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:372.

19. Kao, WF, et al. Ingestion of low-concentration hydrofluoric acid: An insidious and potentially fatal poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:35.

20. Arévalo-Silva, C, et al. Ingestion of caustic substances: A 15-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1422.

21. Riffat, F, Cheng, A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:89.

22. Ryu, HH, et al. Caustic injury: Can CT grading system enable prediction of esophageal stricture? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:137.

23. Bicakci, U, et al. Minimally invasive management of children with caustic ingestion: Less pain for patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:251.

24. Lee, M. Caustic ingestion and upper digestive tract injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1547.

25. Fulton, J, Hoffman, R. Steroids in second degree caustic burns of the esophagus: A systematic pooled analysis of fifty years of human data: 1956-2006. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:402.

26. Huang, YC, Ni, YH, Lai, HS, Chang, MH. Corrosive esophagitis in children. Pediatric Surg Int. 2004;20:207.

27. Blodgett, DW, et al. Fatal unintentional occupational poisonings by hydrofluoric acid in the U.S. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:215.

28. Bjornhagen, V, et al. Hydrofluoric acid–induced burns and life-threatening systemic poisoning: Favorable outcome after hemodialysis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:855.

29. Heard, K, Delgado, J. Oral decontamination with calcium or magnesium salts does not improve survival following hydrofluoric acid ingestion. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:789.

30. Litovitz, T, Schmitz, BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: An analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992;89:747.