CHAPTER 4 Cataract surgery

An introduction

The need for cataract surgery

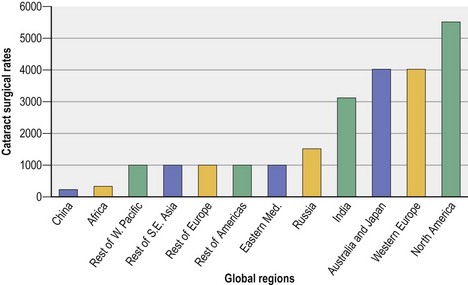

If the CSR is 2000–3000, or more people who become blind due to cataract will be treated, the backlog will be abolished over a period of approximately 5 years. This applies if a visual acuity of <6/60 is used as the indication for surgery; a higher visual acuity cut-off will increase the required CSR. Figure 4.1 shows the CSR in WHO defined regions; only four regions have an adequate rate and millions of people have minimal or no access to surgery1.

Cataract surgery outcomes

The solution to the world’s unmet need would seem to be increasing the number of operations but it is not sufficient to simply perform more surgery; the visual result of the procedure must be of the highest possible standard. Cataract surgery is a potentially sight restoring operation and our aim as surgeons must be to deliver the best possible visual outcomes with the lowest possible complication rate. Continuous monitoring of both individual and national outcomes is well-established practice in all modern eye units. Unfortunately this practice is not always a priority in developing countries where resources are scarce and a culture of audit and accountability is not necessarily well established. Yorston et al.2 have established the role of prospective monitoring in improving surgical outcomes.

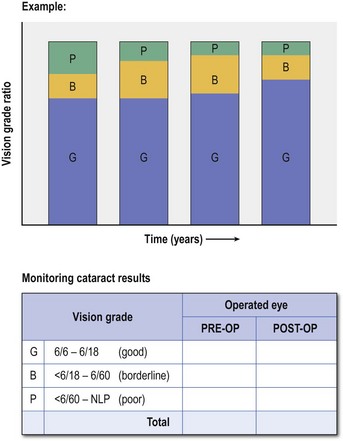

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined standards for the outcomes of cataract surgery (Fig. 4.2). There are three categories: Good (postoperative visual acuity outcome better than 6/18); Borderline (visual acuity outcome in the range 6/18–6/60); and Poor (visual acuity less than 6/60). The WHO recommendations for acceptable outcomes at 1 day postoperation are 40% cases achieving acuity between 6/6 and 6/18 (Good result); 50% of cases achieving a visual acuity between 6/24 and 6/60 (Borderline result); and no more than 10% cases at less than 6/60 (Poor result) with half of those due to intraoperative complications. In many situations it is difficult to obtain follow-up at 6–8 weeks, but by then the recommendations have risen to 85% of cases with a Good outcome and only 5% with a Poor outcome. Factors determining surgical outcome include ocular co-morbidity, the availability of preoperative biometry, surgical expertise/facilities and correction of residual refractive error.

Fig. 4.2 WHO Prevention of Blindness Programme Chart.

Reproduced with permission from Foster A. Cataract: Epidemiology and Service Delivery. Chapter 3. Survey of Ophthalmology 45, Supplement 1:S32–44, 2000.

Monitoring cataract surgical outcomes is crucial if the quality of surgery is to be improved over time. Poor results will constitute a significant barrier to cataract surgery uptake in any given service. Large population-based studies suggest a wide variation in surgical outcomes depending on the procedure performed. National data on the results of phacoemulsification surgery in the UK and Western Europe suggest that over 80% of patients achieve a final visual acuity of 6/12 or better with a complication rate of 4%, although a more recent study has analysed the complication rate in more detail and according to risk stratification3. Data from Eastern Africa and India show a wide variation in final visual acuity ranging between 38 and 80% of patients achieving 6/18 or better with a complication rate between 7 and 20% of cases. Many of these studies include patients undergoing extracapsular, intracapsular and even couching procedures so direct comparisons are not possible4–12.

Global inequalities in eye care provision – VISION 2020 The Right To Sight

The concept of global health care has emerged as a responsibility every developed nation increasingly accepts. Approximately 18 million people are blind from cataract world wide, the vast majority in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe. Projected figures suggest that this figure will double between 1990 and 2020. VISION 2020 is the global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness (Fig. 4.3). It was launched in 1999, jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) with an international membership of NGOs, professional associations, eye care institutions and corporations. Over two decades, it is hoped that VISION 2020 will prevent 100 million people from becoming blind. One of the principal objectives is ‘to provide cataract surgical services at a rate adequate to eliminate the backlog of cataract over a number of years, at a price that is affordable for all people, both rural and urban, in an equitable manner, and with a high success rate in terms of visual outcome and improved quality of life’. Some of the strategies that have been proposed to meet this target include creating a sustainable demand for cataract services. In order to achieve this, barriers to the uptake of existing services must be overcome. A degree of unmet need for surgery is present in all health care systems, but the reasons may well vary according to local economic, cultural and social differences. Identifying cases of blind and visually impaired from cataract requires the support of local communities both before surgery and in rehabilitation afterwards. Population screening for new cases should only be performed when surgical services are well-established and can meet demand by increasing the cataract surgical rate. This will necessitate developing local manpower and resources in order to provide services at a cost that all patients can afford.

1 Foster A. Elimination of cataract blindness. Survey Nov. 2000;45:532-543.

2 Yorston D, Gichuhi S, Wood M, et al. Does prospective monitoring improve cataract surgery outcomes in Africa? Br J Ophth. 2002;86:543-554.

3 Narendran N, Jaycock P, Johnston RL, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55567 operations: risk stratification for posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss. Eye. 2008;23:31-37.

4 Desai P, Minassian DC, Reidy A. The National Cataract Surgery Survey 1997–8: a report of the clinical outcomes. Br J Ophth. 1999;83(12):1336-1340.

5 Minassian DC, Rosen P, Dart JK. Extracapsular cataract extraction compared with small incision surgery by phacoemulsification: a randomised trial. Br J Ophth. 2001;85(7):822-829.

6 Murphy C, Tuft SJ, Minassian DC. Refractive error and visual outcome after cataract extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(1):62-66.

7 Lundstorm M, Barry P, Leite E. 1998 European Cataract Outcome Study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(8):1176-1184.

8 Yorston D, Foster A. Audit of extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber lens implantation for age- related cataract in east Africa. Br J Ophth. 1999;83(8):897-901.

9 Prajna NV, Chandrakarta KS, Kim R. The Madurai Intraocular Lens Study. II: Clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125(1):14-25.

10 Schemann JF, Bakayoko S, Coulibaly S. Traditional couching is not an effective alternative procedure to cataract surgery in Mali. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7(4):271-278.

11 Limburg IT, Foster A, Vaidyanathan K. Monitoring visual outcome of cataract surgery in India. Bull WHO. 1999;77(6):455-460.

12 Gogate P, Vakil V, Khandekar R. Monitoring and modernization to improve visual outcomes of cataract surgery in a community eyecare center in western India. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(2):328-334.