Care of the sick child

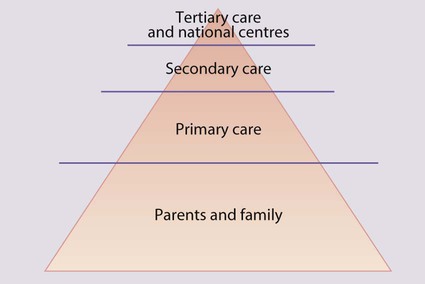

Most sick children are cared for by their parents at home. Medical management is initially given by general practitioners or, in some countries, primary care paediatricians. Most hospital admissions are at secondary care level. A smaller number of children will require tertiary care in a specialist centre, e.g. paediatric intensive care unit, cardiac or oncology unit. Most specialist centres now share care within clinical networks, with the centre linked to a number of surrounding hospitals. For very rare and complex treatments, e.g. organ transplantation and craniofacial surgery, there are a few national centres (Fig. 5.1).

Primary care

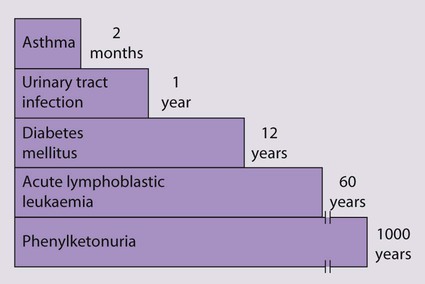

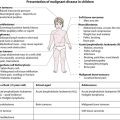

The majority of acute illness in children is mild and transient (e.g. upper respiratory tract infection, gastroenteritis) or readily treatable (e.g. urinary tract infection). Although serious conditions are uncommon (Fig. 5.2), they must be identified promptly. The condition of sick children, especially infants, may deteriorate rapidly, and parents require rapid access to a general practitioner or other healthcare professionals working in primary care, who in turn require ready access to secondary care. Advice may also be obtained from a health professional by telephone, e.g. via NHS Direct, via the internet with NHS Direct Online or by NHS Direct cable TV services. Although an individual general practitioner will care for relatively few children with serious chronic illnesses (e.g. cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus) or disability (e.g. cerebral palsy), each affected child and family are likely to require considerable input from the whole of the primary care team.

Hospital care

Accident and Emergency

Approximately 3 million children (1 in 4) attend an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department each year in England and Wales. The services which should be provided for children are shown in Box 5.1. The number of departments able to meet these expectations is increasing, often by creating a dedicated children’s A&E department.

Hospital admission

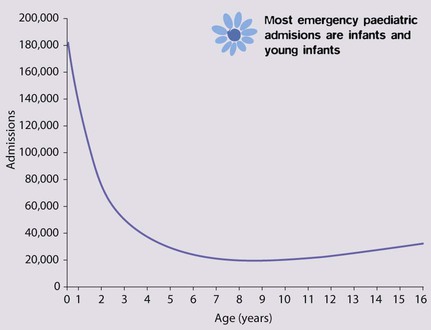

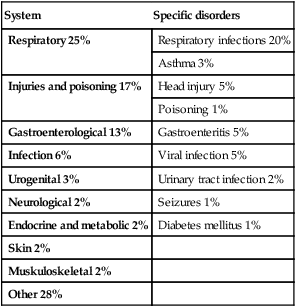

In England and Wales, 1.9 million, i.e. 1 in 6 children is admitted to hospital each year, representing 16% of all hospital admissions. About 60% of acute admissions are under the care of paediatricians, and the remainder are surgical patients (although a paediatrician is also involved in their care while they are in hospital, to oversee any medical requirements) (Fig. 5.3). Most paediatric admissions are of infants and young children under 5 years of age and are emergencies, whereas surgical admissions peak at 5 years of age, one-third of which are elective. The reasons for medical admission are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Reason for emergency admission of children <15 years old to hospital

| System | Specific disorders |

| Respiratory 25% | Respiratory infections 20% |

| Asthma 3% | |

| Injuries and poisoning 17% | Head injury 5% |

| Poisoning 1% | |

| Gastroenterological 13% | Gastroenteritis 5% |

| Infection 6% | Viral infection 5% |

| Urogenital 3% | Urinary tract infection 2% |

| Neurological 2% | Seizures 1% |

| Endocrine and metabolic 2% | Diabetes mellitus 1% |

| Skin 2% | |

| Muskuloskeletal 2% | |

| Other 28% |

Data based on 58 061 admissions, 2009–2010. ISD, Scotland.

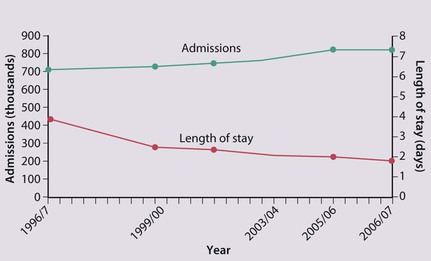

Although primary and community health services for children have improved markedly over the last decade, the hospital admission rate has continued to rise, although it may now be plateauing (Fig. 5.4). The reasons for this are unclear, but probably include:

• Lower threshold for admission: there appears to be an increased expectation of hospital admission by parents and medical staff worried that the child’s clinical condition may deteriorate

• Repeated hospital admission of children with complex conditions who would have died in the past but are now surviving, e.g. very low birthweight infants from neonatal intensive care units, children with cancer or organ failure.

Strenuous efforts are made to reduce the rate and length of hospitalisation (Fig. 5.4):

• Speciality of ambulatory paediatrics has been developed; it encompasses specialist paediatricians providing hospital care for immediate medical problems outside inpatient paediatric wards

• Dedicated children’s short stay beds within or alongside the A&E department are increasingly available to allow children to be treated or observed for a number of hours and discharged home directly, avoiding the need for admission to the ward

• Day-case surgery has been instituted for many operations which used to require overnight stay.

• Day units are used for complex investigations and procedures instead of inpatient wards

• Shared care may be provided between hospitals and primary care, with paediatricians and other healthcare professionals seeing children at home or in primary care settings

• Homecare teams aim to provide care in the child’s home and thereby reduce hospital attendance, admission and length of stay. Most teams comprise community paediatric nurses, but some include doctors, and either cover all aspects of paediatric care within a geographical area or are for a specific condition, e.g. cystic fibrosis or malignancy, usually centred around a tertiary referral centre. The problems managed at home by such teams include:

– Changing postoperative wound dressings or managing burns

– Day-to-day management and support for the family for chronic illnesses, e.g. diabetes mellitus, asthma and eczema

– Specialist care, e.g. home oxygen therapy, intravenous infusions via a central venous catheter (e.g. antibiotics or chemotherapy) or peritoneal dialysis

– Symptom and pain control and emotional support of terminally ill children (Fig. 5.5)

• Children’s hospices provide respite or terminal care for children with life-threatening conditions, including malignancy disease, neurodegenerative, metabolic and other disorders.

• Some teams provide a ‘hospital at home’ service for children who are acutely ill, in order to avoid hospitalisation.

Pain

Chronic pain

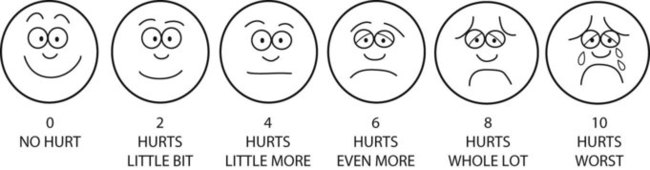

Older children can describe the nature and severity of the pain they are experiencing. In younger children, assessing pain is more difficult. Observation and parental impression are commonly used and a number of self-assessment tools have been designed for children over 3 years old (Fig. 5.6).

Management

The approaches to pain management are listed in Box 5.2. This should allow pain to be prevented or kept to a minimum. Age-appropriate explanation should be given when possible and the approach be reassuring; however, it is imperative not to lie to children, otherwise they will lose trust in what they are told in the future. Distraction techniques such as blowing bubbles, telling stories, holding family toys or playing computer games, as well as the involvement of trained play specialists, can be highly successful in ameliorating pain in children. Some children develop particular preferences for a particular venepuncture site or distraction technique, and this should be accommodated as far as possible.

Breaking bad news

• a serious congenital abnormality at birth, e.g. chromosomal disorder

• the diagnosis of a disabling condition, e.g. cerebral palsy, neurodegenerative disorder, gross intracranial abnormality seen at ultrasound in pre-term infants

• a serious illness, e.g. meningitis or malignant disease, or an accident, e.g. head injury

• sudden death of a child, e.g. sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Initial interview

The manner in which the initial interview is conducted is very important. It may have a profound influence on the parents’ ability to cope with the problem and their subsequent relationship with health professionals. Parents often continue to recall and recount, for many years, details of the initial interview when they were informed that their child had a serious problem. Parents of children with life-threatening illnesses have said that what they valued most was open, sympathetic, direct and uninterrupted discussion in private that allowed sufficient time for doctors to repeat and clarify information and for them to ask questions (Box 5.3).

Discharge from hospital

• The reason for admission and any implications for the future

• Details of medication and other treatment

• Any clinical features which should prompt them to seek medical advice, and how this should be obtained

• The existence of any voluntary self-help groups if appropriate

• Problems or questions likely to be asked by other family members or in the community. These should be anticipated by the doctor and discussed. What do the nursery or school, baby-sitters or friends need to know? What about sports, etc?

• Suitability of home circumstances needs to be assessed, particularly when the home requires adaptation for special needs

• Social support may need to be arranged, especially in relation to child protection

• Medical information should be added to the child’s personal child health record

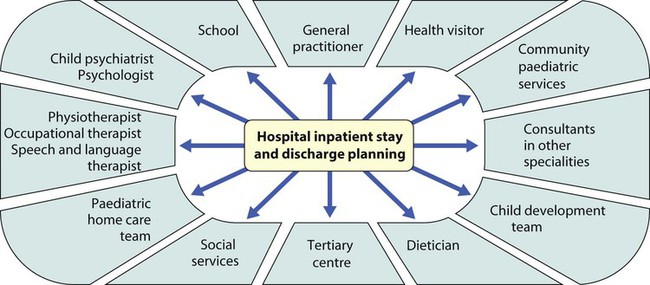

• Consider which professionals should be informed about the admission and what information it is relevant for them to receive. This must be done before or at the time of discharge. The aim is to provide a seamless service of care, treatment and support, with the family and all the professionals fully informed (Fig. 5.7). This can be facilitated for children with a chronic illness or disability by having a key worker to coordinate their care.

Ethics

Definitions of the principles of medical ethics

• Non-maleficence – do no harm (psychological and/or physical)

• Beneficence – positive obligation to do good (these two principles have been part of medical ethics since the Hippocratic Oath)

• Justice – fairness for all, equity and equality of care

• Respect for autonomy – respect for individuals’ rights to make informed and thought-out decisions for themselves in accordance with their capabilities

• Truth-telling and confidentiality – important aspects of autonomy that support trust, essential in the doctor–patient relationship

• Duty – the moral obligation to act irrespective of the consequences in accordance with moral laws which are universal, apply equally to all and which respect persons as autonomous beings

• Utility – the obligation to do the greatest good for the greatest number

• Rights – justifiable moral claims, e.g. the right to life, respect, education, which impose moral obligations upon others.

The ethics of research in paediatrics

Whatever the nature of the research a number of criteria must be met:

• Appropriate research should be first carried out in adults or older children.

• The project should have a sound scientific basis and be well designed.

• The researchers should be competent to carry it out in the time specified.

• Sufficient information should be given in a form comprehensible to the child and family to enable them to give valid consent to participation, e.g. by provision of information sheets in an appropriate form and language or by the use of independent translators.

• Parents must have the option to withdraw their child from the research at any stage without prejudice.

• The project must be reviewed and approved by an independent scientific and ethical process (Research Ethics Committee).

Evidence-based paediatrics

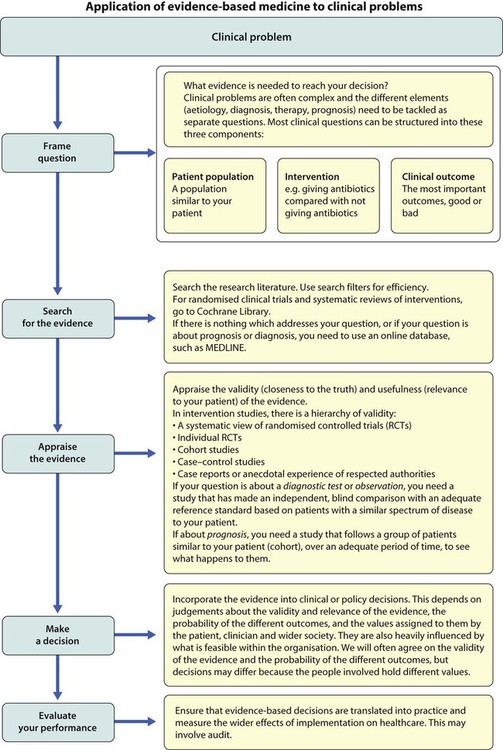

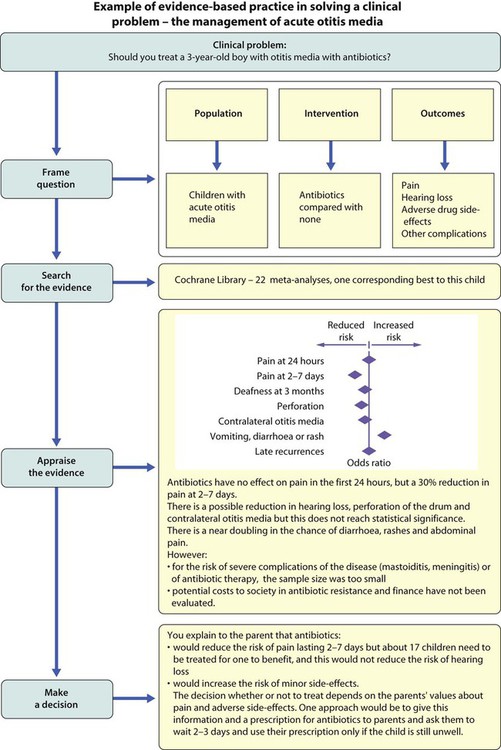

Clinicians have always sought to make decisions in the best interests of their patients. However, such decisions have often been made intuitively, given as clinical opinion, which is difficult to generalise, scrutinise or challenge. Evidence-based practice provides a systematic approach to enable clinicians to efficiently use the best available evidence, usually from research, to help them solve their clinical problems. The difference between this approach and old-style clinical practice is that clinicians need to know how to turn their clinical problems into questions that can be answered by the research literature, to search the literature efficiently, and to analyse the evidence, using epidemiological and biostatistical rules (Figs 5.8, 5.9). Sometimes, the best available evidence will be a high-quality systematic review of randomised controlled trials, which are directly applicable to a particular patient. For other questions, lack of more valid studies may mean that one has to base one’s decision on previous experience with a small number of similar patients. The important factor is that, for any decision, clinicians know the strength of the evidence, and therefore the degree of uncertainty. As this approach requires clinicians to be explicit about the evidence they use, others involved in the decisions (patients, parents, managers and other clinicians) can debate and judge the evidence for themselves.

Why practise evidence-based paediatrics?

• Blindness from retinopathy of prematurity. In the 1950s, following anecdotal reports, many neonatal units started nursing all premature infants in additional ambient oxygen, irrespective of need. This reduced mortality, but as no properly conducted trials were performed of this new therapy, it took several years for it to be realised that it was also responsible for many thousands of babies becoming blind from retinopathy of prematurity.

• Advice that babies should sleep lying on their front (prone), which increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Medical advice given during the 1970s and 1980s, to put babies to sleep prone, appears to have been based on physiological studies in preterm babies, which showed better oxygenation when nursed prone. Furthermore, autopsies on some infants who died of SIDS showed milk in the trachea, which was assumed to have been aspirated and this was thought to be more likely if they were lying on their back. However, an accumulation of more valid evidence from cohort and case–control studies showed that placing term infants prone was associated with an increased risk of SIDS.

To what extent is paediatric practice based on sound evidence?

There are two paediatric specialities in which there is a considerable body of reliable, high-quality evidence underpinning clinical practice, namely paediatric oncology and, to a lesser extent, neonatology. Management protocols of virtually all children with cancer are part of multicentre trials designed to identify which treatment gives the best possible results. The trials are national or, increasingly, international, and include short- and long-term follow-up. Examples of the range of evidence available in paediatrics are given in Box 5.4. In general, the evidence base for paediatrics is poorer than in adult medicine. Reasons for this include:

• The relatively small number of children with significant illness requiring investigation and treatment. To overcome this, multicentre trials are required, which are more difficult to organise and expensive.

• Additional ethical limitations

– Subjecting children to additional investigations or giving a new treatment is severely limited by the inability of the child to give consent. Some parents are concerned that participating in a trial could mean that their child could receive treatment that turns out to be inferior to the standard treatment and could have unknown side-effects.

– There is concern over the ability of parents to give truly informed consent immediately after the acute onset of serious illness, e.g. the birth of a preterm infant, meningococcal septicaemia or meningitis.

• There is limited investment by the pharmaceutical industry in drug trials, as drug use in children is insufficient to justify the cost and ethical difficulties of conducting trials. As a result, approximately 50% of drug treatments in children are unlicensed (‘off label’).