24 Cardiac Tumor: Rhabdomyoma

I. CASE

A. Fetal echocardiography findings

a. The fetal echo reveals situs solitus of the atria, levocardia, left aortic arch, and heart rate of 150 bpm.

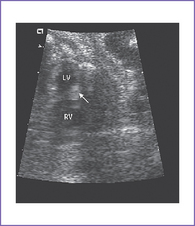

b. The four-chamber view is abnormal, with normal-sized ventricles each with echogenic masses in the walls.

c. The cardiac axis, position, and size are normal (cardiothoracic ratio = 0.3).

d. There is no evidence of compromise of the cardiac flows by color Doppler examination, but there is localized decreased left ventricle (LV) wall motion near one of the masses (Fig. 24-1A).

e. The inferior vena cava (IVC) is not dilated and has a normal blood flow pattern and velocity.

f. The systolic ventricular function of the right ventricle (RV) is normal.

g. There is no ascites or truncal edema.

h. Umbilical venous and arterial flow patterns are normal.

i. The aortic arch is leftward, and the ductal and aortic arches are of similar size. Both arches have antegrade flow.

j. Flow through the foramen ovale is unrestricted with a bidirectional shunt.

k. The pulmonary venous flow pattern is normal.

l. RV and LV Tei indices (myocardial performance index) are normal.

m. The ventricular walls show many small echogenic foci consistent with multiple tumors.

a. Similar intracardiac anatomy as twin A is seen but without congenital heart disease.

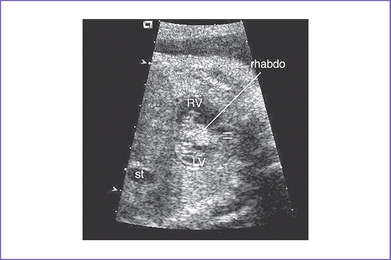

b. The RV apex contains a spherical echogenic tumor typical of rhabdomyoma (see Fig. 24-1B).

D. Fetal management and counseling

1. Amniocentesis was not offered because the risk from amniocentesis is probably higher than the risk of abnormal karyotype in cardiac tumor.

2. Follow-up included serial antenatal studies at 4-week intervals.

c. Arrhythmias such as ventricular or atrial ectopy or tachycardia can result from a focus near a tumor.

d. Imaging of the fetal brain could reveal subependymal nodules as well as cortical tumors (diagnosed by MRI) suggesting tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).

F. Neonatal management

a. Evaluation should include standard vital signs, pulse oximeter, and blood pressures.

b. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is obtained to evaluate for arrhythmias or signs of myocardial ischemia.

c. An echocardiogram is immediately performed to assess ventricular function and outflow tracts.

a. Surgery is only indicated when there is critical inflow or outflow obstruction by the tumor, resulting in hemodynamic compromise with or without the need for ductal patency. In such a situation, the tumor should be resected.

b. Arrhythmia with incessant tachycardia and compromised hemodynamics could be managed with surgical resection, but with mapping of which tumor is causing the abnormal rhythm. However, with multiple cardiac tumors, it may be impossible to detect the source of the arrhythmia.

H. Risk of recurrence

1. TSC is a hamartoma syndrome caused by mutations in either of two tumor-suppressor genes: TSC1 or TSC2.

2. TSC is autosomal dominant with variable expressivity.

3. It occurs in 1/6,000 live births, prevalence of 1/10,000 births, and about 80% are caused by de novo mutation.

4. New diagnostic criteria for TSC were established in 1992 and revised in 1998. Family history of TSC is no longer a criterion for TSC but is an important clue for considering the diagnosis.

5. Genetic DNA testing of the fetal amniotic fluid for TSC1 and TSC2 genes is available. If the test is positive, both parents will be examined clinically and DNA tested to rule out TSC.

6. Multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas detected prenatally or in early infancy are no longer sufficient to establish the diagnosis of TSC.

I. Outcome of this case

a. The affected twins were born with Apgar scores of 9 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes and appropriate weight for gestation.

b. There were no apparent dysmorphic features.

c. The babies were hemodynamically stable, and postnatal echocardiogram confirmed the presence of multiple echogenic masses in the LV consistent with rhabdomyomas.

d. Baseline ECG was normal, and monitoring over 24 hours showed no persistent arrhythmia apart from occasional premature ventricular contractions. The babies were discharged home in stable condition.

a. At 5 years of age, the masses had completely resolved and the echocardiogram was normal. Accordingly, the twins were discharged from cardiology.

b. However, the boy was noted to have developmental delay, showed a shagreen patch on the skin, and developed a complex seizure disorder. Clinical manifestations of TSC include epilepsy, learning difficulties, behavioral problems, and skin lesions. The diagnosis of TSC was confirmed.

c. The parents and siblings had negative clinical examinations, CT scan, echocardiography, and genetic testing.

d. In some institutions, physical examination, brain CT scan, and echocardiography are done on all parents. If a mutation is found in the fetus, the parents and their other children are checked. If mutation is not found and the parents have no clinical signs of TSC on physical examination, future pregnancies are carefully followed, including echocardiography.

II. YOUR HANDY REFERENCE

B. Outcome

1. The natural history of most tumors detected prenatally is favorable, and most tumors regress beyond the second trimester; however, in rare cases, there is progression in utero.

2. After birth, large tumors can affect the cardiac output, necessitating surgical resection or anticongestive medication.

3. The majority of cases have a benign perinatal course, with delivery at term, continued regression in size, and even complete resolution of more than 80% of the tumors within infancy and early childhood. No major neonatal or postnatal cardiac complications have occurred after regression.

C. Associated syndromes and extracardiac anomalies

1. Cardiac tumors, mainly rhabdomyoma or fibroma, or pericardial tumors such as teratoma, are rarely associated with extracardiac malformations or with chromosomal anomalies.

2. In a study by Bader and colleagues (2003), the majority of cardiac rhabdomyomas detected before birth (80%) were associated postnatally with TSC.

D. Clues to fetal sonographic diagnosis

1. Rhabdomyoma usually shows multiple echogenic foci involving either one or both ventricles (Fig. 24-2).

2. Fibroma usually has a single echogenic focus involving either one or both ventricles and is confined to the myocardium. Prenatal arrhythmia (mostly ventricular) could be a presenting feature.

3. Intrapericardial teratomas usually arise from the base of the heart, are attached to the aortic root and/or pulmonary trunk, and are often wedged between the aortic root and the SVC. They can impinge on cardiovascular structures.

a. They manifest prenatally with a pericardial effusion, usually in the second or third trimester.

b. They may be associated with progressive fetal cardiovascular and placental vascular compromise resulting in hydrops, which occurs in more than three fourths of cases.

E. General diagnostic signs

1. Postnatal diagnosis of rhabdomyoma is often made when signs of TSC are identified or when there is a family history.

2. In contrast, prenatal diagnosis of cardiac rhabdomyomas usually occurs after the tumors are seen on fetal ultrasound or when fetal dysrhythmia is detected.

a. They are usually seen in the second trimester.

b. They are usually well tolerated (4%-5% fetal loss).

c. They are often associated with dysrhythmias (up to 50%).

d. Tumors can progress in the first and second trimesters, but they usually regress thereafter.

3. SBE prophylaxis is indicated as long as there is outflow tract obstruction.

4. Neurologic surveillance is recommended for seizure disorder and developmental delay.

5. One or two yearly outpatient follow-up visits with a 12-lead ECG and echocardiogram are recommended.

6. If there is any history of unexplained palpitations or abnormal heart rhythm, a metabolic stress test with 24-hour Holter monitoring is recommended.

F. Cardiovascular profile score

1. The score is 10/10 if there are no abnormal signs and reflects two points for each of five categories: Hydrops, venous Doppler, heart size, cardiac function, and arterial Doppler.

2. Serial prenatal follow-up can help in:

a. Diagnosis of heart failure and hydrops fetalis.

b. Timing of fetal intervention (e.g., pericardiocentesis or fetal surgery) as in cases of pericardial teratoma or rhabdomyoma.

H. Immediate postnatal management for patients without prenatal diagnosis

1. If the baby is hemodynamically stable with normal vital signs, the masses will not be diagnosed at birth because the baby is asymptomatic. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test.

2. If the baby is hemodynamically unstable (e.g., low blood pressure resulting from ventricular outflow obstruction, persistent arrhythmia), the baby should be transferred to the neonatal or pediatric (cardiac if available) intensive care unit (ICU) for further assessment and management.

III. TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

A. Diagnosis

1. Prenatal and postnatal DNA genetic testing for the TSC1 or TSC2 genes is available.

2. Cardiac rhabdomyoma is the most common fetal cardiac tumor.

3. Cardiac rhabdomyoma diagnosed in utero is usually associated with TSC postnatally.

4. Rhythm disturbance can be the presenting feature of fetal cardiac fibroma.

Bader RS, Chitayat D, Kelly E, et al. Fetal rhabdomyoma: Prenatal diagnosis, clinical outcome, and incidence of associated tuberous sclerosis complex. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5):620-624.

Chitayat D, McGillivray BC, Diamant S, et al. Role of prenatal detection of cardiac tumours in the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis–report of two cases. Prenat Diagn. 1988;8:577-584.

Crawford DC, Garrett C, Tynan M, et al. Cardiac rhabdomyomata as a marker for the antenatal detection of tuberous sclerosis. J Med Genet. 1983;20:303-304.

Cyr DR, Guntheroth WG, Nyberg DA, et al. The in utero diagnosis of an interventricular septal cardiac rhabdomyoma by means of realtime-directed, M-mode echocardiography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;143:967-969.

Ek M. Prenatal diagnosis of an intrapericardial teratoma: A cause for nonimmune hydrops. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;7:87-90.

Farooki ZQ, Ross RD, Paridon SM, et al. Spontaneous regression of cardiac rhabdomyoma. Am J Cardio. 1991;67:897-899.

Giacoia GP. Fetal rhabdomyoma: A prenatal echocardiographic marker of tuberous sclerosis. Am J Perinatol. 1992;9:111-114.

Gresser CD, Shime J, Rakowski H, et al. Fetal cardiac tumor: A prenatal echocardiographic marker for tuberous sclerosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:689-690.

Holley DG, Martin GR, Brenner JI, et al. Diagnosis and management of fetal cardiac tumors: A multicenter experience and review of published reports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:516-520.

Khattar H, Guerin R, Fouron J, et al. Les tumeurs cardiaques chez l’enfant: Rapport de 3 observations avec Èvolution spontanèment favorable. Arch Mal Coeur. 1975;68:419-429.

Nadas AS, Ellison RC. Cardiac tumors in infancy. Am J Cardiol. 1968;21:363-366.

Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM. The phakomatoses. Am J Nucl Radiol. 1994;13:725-746.

Smythe JF, Dyck JD, Smallhorn JF, Freedom RM. Natural history of cardiac rhabdomyoma in infancy and childhood. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1247-1249.