Cardiac Pacing

INDICATIONS FOR PERMANENT PACEMAKER IMPLANTATION

Pacing Indications for Sinus Node Dysfunction

INDICATIONS FOR TEMPORARY PACING

Atrioventricular Nodal Dysfunction

High-Grade and Paroxysmal Atrioventricular Block

CONDITIONS THAT DO NOT NORMALLY REQUIRE PACING

ESOPHAGEAL AND TRANSTHORACIC PACING

Prevention of Atrial Arrhythmias

Treatment of Atrial Arrhythmias

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN TEMPORARY PACING

COMPLICATIONS OF PERMANENT PACEMAKER IMPLANTATION

Indications for Permanent Pacemaker Implantation

The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) have jointly engaged in the production of guidelines for cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation, with publication of updated Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities in 2008.1 These recommendations are primarily evidence-based, and this publication includes an extensive review of the literature on the topic. As with other guideline documents, recommendations are classified as class I, II, or III as follows:

• Class I: Benefit  > Risk; the procedure/treatment should be performed/administered.

> Risk; the procedure/treatment should be performed/administered.

• Class II: Conditions for which there is conflicting evidence or divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the procedure.

• Class IIa: Benefit  Risk; it is reasonable to perform the procedure/administer treatment, although additional studies with focused objectives are still needed.

Risk; it is reasonable to perform the procedure/administer treatment, although additional studies with focused objectives are still needed.

• Class IIb: Benefit ≥ Risk; the procedure/treatment may be considered, although additional studies with broad objectives are needed or additional registry data would be helpful.

• Class III: Risk ≥ Benefit; the procedure/treatment should not be performed/administered because it is not helpful and may be harmful.

The level of evidence or weight of evidence to support these recommendations is ranked as follows:

• Level of evidence A: Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses.

• Level of evidence B: Data derived from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies.

• Level of evidence C: Consensus opinion of experts, case studies, or standard of care.

Pacing Indications for Sinus Node Dysfunction

SND is the most common cause of bradyarrhythmias in clinical practice. The typical age at the time of diagnosis of SND appears to be in the seventh or eighth decade of life, with a mean or median age of 71 to 74 years in randomized clinical trials evaluating pacemaker therapy.2–4 However, clinical manifestations of SND may occur at any age and may be secondary to any one of several potential causes, including destruction of the SN, ischemia, infarction, infiltrative disease, surgical trauma, autonomic dysfunction, or endocrinologic abnormalities.1,5

Clinical manifestations of SND are diverse, and symptoms may include fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, dyspnea on exertion, presyncope, lightheadedness, dizziness, or syncope. In the absence of any clearly reversible cause of bradycardia, the only effective treatment for symptomatic bradycardia in patients with SND is permanent pacing. Box 5.1 outlines recommendations for permanent pacing in patients with SND.1

Pacing Indications for Acquired Atrioventricular Block

Third-degree AV block refers to absence of impulse conduction from the atria to the ventricles, and this may be congenital or acquired. Permanent pacing is often indicated for acquired complete block without reversible causes. AV block may also occur in patients with SND, and 20% of patients with SND will have some degree of AV block.4 In addition, following permanent pacemaker implantation for SND, the risk of developing AV block within 5 years of follow-up is 3% to 35%.6–9

Patients with AV block may be asymptomatic, or may have symptoms that vary from mild lightheadedness, dizziness, shortness of breath, or fatigue to presyncope and loss of consciousness. The decision regarding permanent pacemaker implantation should take into account whether or not symptoms are attributable to bradycardia, as well as the cause and “level” of AV block. Completely reversible causes of AV block, such as electrolyte disturbances or Lyme disease, should be excluded. Permanent pacing indications for acquired AV block are summarized in Box 5.2. Pacing indications for chronic bifascicular block and pacing for AV block associated with acute myocardial infarction are outlined in Boxes 5.3 and 5.4.

Other Permanent Pacing Indications

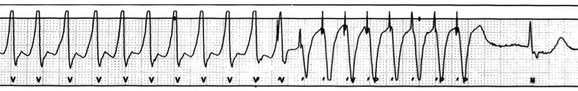

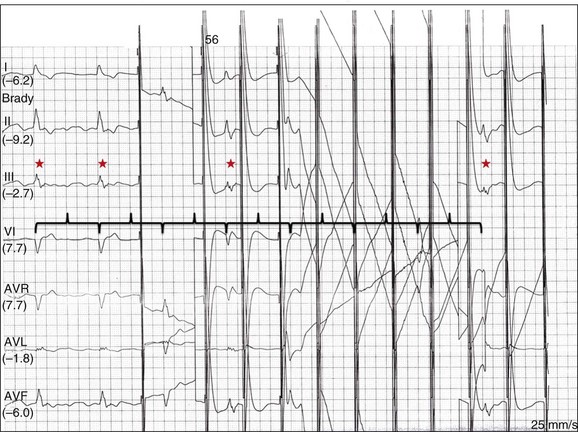

In specific situations, permanent pacing may also be clinically indicated in some patients with carotid sinus hypersensitivity, neurocardiogenic syncope, or obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and following cardiac transplantation.1 Historically, antitachycardia pacemakers were occasionally utilized to treat recurrent supraventricular arrhythmias, but they are rarely used in contemporary practice with the availability of catheter ablation therapy. Pace termination of ventricular tachycardia is frequently utilized for the treatment of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia as part of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy, and can also be used to terminate frequent arrhythmia episodes using a temporary transvenous pacing system in the intensive care setting (Fig. 5.1).

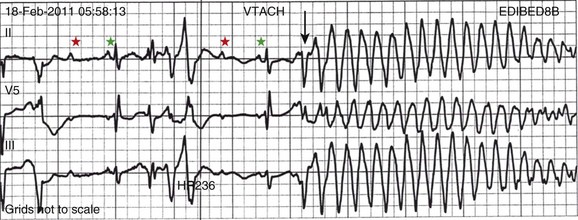

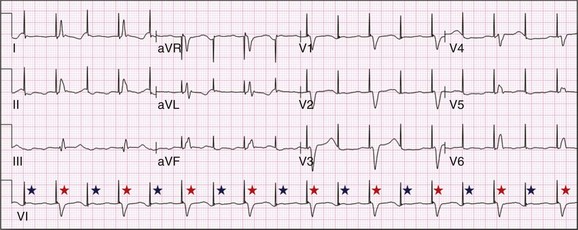

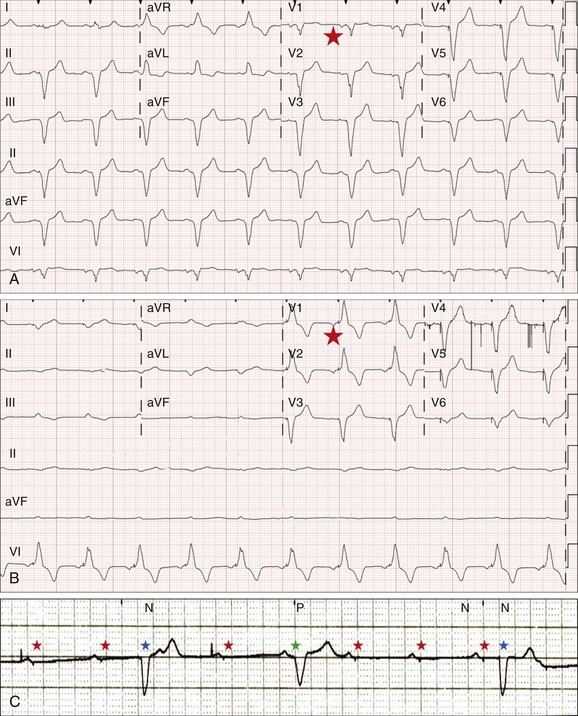

Pacing may be useful in the prevention of pause-dependent, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia as well (Fig. 5.2). Permanent pacing is indicated for pause-dependent ventricular tachycardia, with or without QT prolongation (class I indication, level of evidence C), and is reasonable for high-risk patients with congenital long QT syndrome (class IIb indication, level of evidence B).1 Atrial-based pacing (“AAI” or “DDD” mode) is considered the preferred pacing mode for prevention of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia associated with the congenital long QT syndrome. Pacing the left ventricle can improve hemodynamics in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and bundle branch block by altering the activation sequence and influencing regional contractility, and is particularly effective in patients with left bundle branch block. This is referred to as “biventricular pacing” or “cardiac resynchronization therapy” and is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Indications for Temporary Pacing

Atrioventricular Nodal Dysfunction

The “level” of AV block—whether at the level of the AV node or below the AV node in the His-Purkinje conduction system—is critical in determining the need for temporary pacing. AV nodal block improves with measures that accelerate AV nodal conduction, like atropine, dopamine, and isoproterenol. Infranodal block—that is, block below the level of the AV node at the bundle of His or bundle branches—may paradoxically worsen with these agents owing to downstream block in an already diseased His-Purkinje system. The origin of the escape rhythm—whether “proximal” or “distal” in the cardiac conduction system—predicts both its rate and stability. Complete heart block at the level of the AV node is associated with an escape rhythm arising from the AV junction, His bundle, or proximal fascicles; a narrow QRS morphologic pattern; and a heart rate in excess of 60 beats per minute. Infranodal block is associated with an escape rhythm arising from the bundle branches or even ventricular myocardium, a wide and often bizarre QRS morphologic pattern, and a heart rate in the range of 40 beats per minute.10 Complete heart block with a junctional escape rhythm does not typically require temporary pacing, unless accompanied by hypotension. In contrast, complete heart block with a ventricular escape rhythm is inherently unstable and usually requires temporary pacing, even if hemodynamically stable. History can be quite helpful in risk stratification. A history of syncope in a patient who presents with advanced second-degree AV block may portend a higher degree of AV block or pause-dependent torsades de pointes, and there should be a very low threshold for temporary pacing.11

High-Grade and Paroxysmal Atrioventricular Block

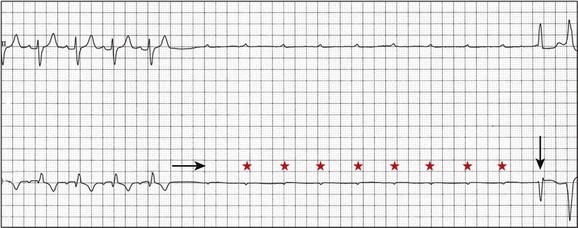

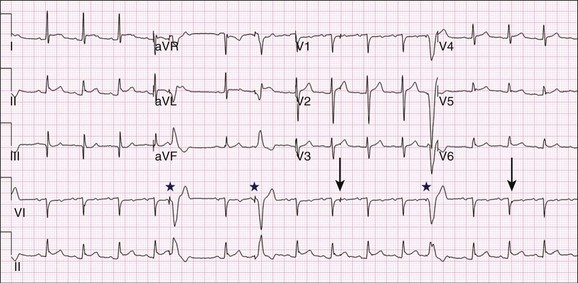

In the critical care setting, it is crucial to distinguish between paroxysmal and vagally mediated AV block. Vagally mediated AV block due to extrinsic, parasympathetic input is characterized by progressive sinus slowing, progressive PR prolongation, Mobitz type I second-degree AV block immediately before the onset of complete heart block, and sinus slowing during the episode (Fig. 5.3). In contrast, high-grade AV block due to an intrinsic failure of a diseased His-Purkinje system—also termed “paroxysmal” AV block—is characterized by a constant sinus rate, or even sinus acceleration during the episode (Fig. 5.4). Patients with paroxysmal AV block usually have some sort of baseline conduction abnormality on their surface 12-lead electrocardiogram—most commonly, right bundle branch block—but this finding is not absolute. The hallmark of paroxysmal AV block is immediate transition from apparently normal conduction to complete AV block and ventricular asystole. This is usually triggered by a pause after a premature atrial or ventricular depolarization, but vagally mediated sinus slowing can have the same effect, complicating the interpretation of these events. Vagally mediated heart block is typically benign, is atropine responsive, and does not require temporary pacing. Paroxysmal AV block can be fatal and requires temporary transvenous pacing until a permanent pacemaker can be placed.12

Electrolyte and Metabolic Derangement

Hyperkalemia can precipitate complete AV block and can also elevate pacing thresholds in permanent pacemaker systems.13–15 A progressive increase in extracellular potassium raises the resting membrane potential, inactivating voltage-gated sodium channels that depend upon a sufficiently negative resting membrane potential for normal function. The effect is more pronounced in the atrium and ventricle than the cells of the specialized conduction system, explaining why the characteristic changes in the P wave and QRS complex typically precede sinoatrial (SA) and AV nodal dysfunction: “peaked” T waves and QT shortening (potassium level 5.5 mEq/L); PR prolongation and QRS widening (potassium level 6.5 mEq/L); a “sinoventricular” rhythm, due to the apparent absence of atrial activity (potassium level 8-9 mEq/L); and lastly, a “sine wave” pattern due to merging of the QRS and T wave that predicts impending cardiac arrest (potassium level 10 mEq/L).16 Nevertheless, the 12-lead electrocardiogram may be entirely normal in cases of pronounced hyperkalemia, and AV block may occur in isolation.17–20 Therefore, a routine metabolic evaluation is indicated in all patients with new conduction deficits.

Case reports and animal studies suggest a link between metabolic acidosis and heart block, and metabolic acidosis frequently accompanies hyperkalemia in the setting of chronic kidney disease.21 The administration of sodium bicarbonate acutely raises extracellular pH and indirectly lowers extracellular potassium, and may improve responsiveness to vasopressors in emergent situations.22

Hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia have not been implicated in heart block.

Drug Side Effects

A number of drugs can cause severe sinus bradycardia, AV block, or both. β-Adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers are both negatively chronotropic and inotropic, and their administration can result in significant bradycardia and hypotension, particularly in overdose. Digoxin toxicity may present with high-grade or complete AV block, further compounded by atrial or ventricular tachycardia due to increased automaticity. Amiodarone, dronedarone, and sotalol—class III antiarrhythmic drugs with mixed antiarrhythmic effects—frequently cause bradycardia due to SA or AV conduction defects. Some studies suggest that drug-induced AV block—particularly at therapeutic levels—is a predictor of future conduction disorders.23

Clearly, the initial treatment is discontinuation of the offending drug(s). Directed therapy may occasionally be useful as well, but the evidence is largely anecdotal. β-Adrenergic blocker toxicity may respond to glucagon, and calcium channel blocker toxicity may respond to calcium or glucagon in refractory cases.24–28 Vasopressors are occasionally necessary because of the vasodilatory and negative inotropic effects of these drugs. Digoxin toxicity can be treated with digoxin antibody fragments (Digibind).29 If hemodynamic instability persists in the setting of severe bradycardia, temporary pacing is indicated. β-Adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers increase pacing thresholds in permanent devices; if failure to capture is noted in a patient with suspected overdose of these agents, a temporary increase in pacing output may solve the problem.30

Infectious Disease

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne illness in North America.31 Erythema migrans is sufficient for diagnosis, but most patients cannot recall a tick exposure or rash.32 The diagnosis of Lyme carditis requires serologic testing for confirmation, and Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies are positive in the vast majority of patients with the disease.33 Regardless of patient history, the diagnosis of Lyme carditis should always be entertained in a patient presenting with heart block in an endemic area. Typically, Lyme carditis affects the AV node and is associated with a stable, junctional escape rhythm, but more diffuse involvement of the His-Purkinje system with a slower, more unstable escape is also possible.34 Although conduction deficits regress rapidly and completely with appropriate antibiotic therapy, temporary pacing is occasionally necessary.

Infective endocarditis can be complicated by a broad spectrum of conduction disturbances, including first-degree AV delay, bundle branch block, and complete heart block. Any new conduction deficit suggests perivalvular abscess, due to the proximity of the compact AV node and bundle branches to the membranous septum.35,36 Conduction disturbances most commonly complicate aortic valve endocarditis, but the tricuspid valve and mitral valve are also susceptible.37–39 Perivalvular abscess and heart block are indications for surgical repair.40 Serial 12-lead electrocardiography should be performed in all patients with endocarditis, and temporary pacing should be strongly considered for any progressive conduction disturbance.

Lymphocytic and giant cell myocarditis are typically associated with acute systolic dysfunction, but they can also be complicated by severe electrical abnormalities, including complete heart block. Lymphocytic myocarditis carries a more favorable prognosis than giant cell myocarditis, but permanent pacemaker dependency is possible with either condition.41

After Myocardial Infarction

Official guidelines for temporary and permanent pacing after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction were last updated in 2004, and permanent pacemaker indications following myocardial infarction were updated in 2008 as previously discussed.1,42 Recommendations for temporary pacing are largely based on expert opinion, in addition to case reports, case series, and published summaries from before the reperfusion era.

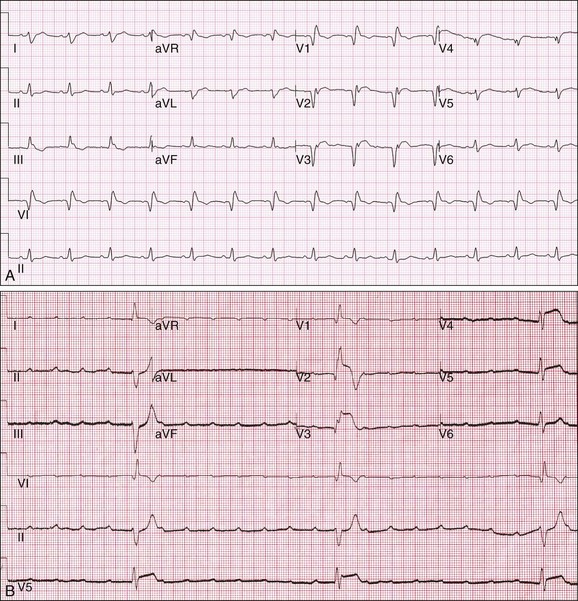

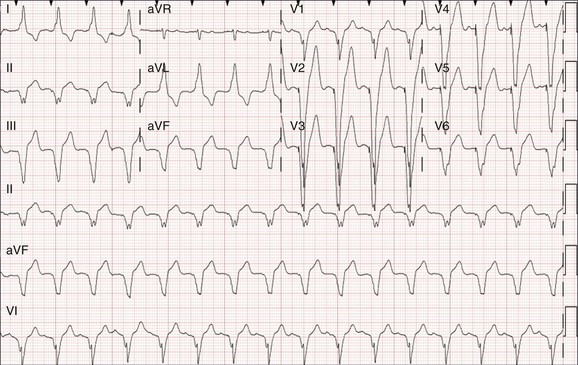

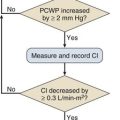

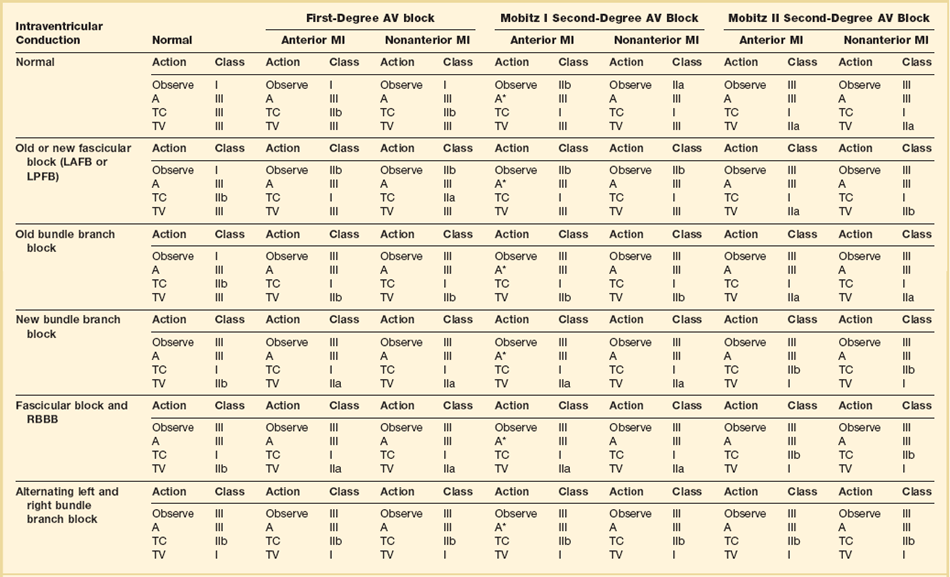

The need for temporary pacing is frequently made at the time of percutaneous intervention by the interventional cardiologist, but familiarity with official guidelines and an understanding of the risk of progression is critical in the appropriate management of the patient after myocardial infarction. Clearly, myocardial infarction complicated by asystolic arrest and symptomatic bradycardia justifies temporary transvenous pacing. Temporary transvenous pacing is recommended when an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is complicated by new bifascicular block or complete bundle branch block and concomitant Mobitz type II second-degree AV block, regardless of the culprit artery. It is also recommended for alternating bundle branch block, regardless of the status of AV conduction. Alternating bundle branch block—right bundle branch block alternating with left bundle branch block, or bifascicular block with right bundle branch block and alternating left anterior and posterior fascicular block—is a marker of severe His-Purkinje disease. In particular, bifascicular block with right bundle branch block and left posterior fascicular block carries a very poor prognosis with a high risk of progression to complete heart block (Fig. 5.5A and B).43 In cases of Mobitz type II second-degree AV block with normal intraventricular conduction, fascicular block, and old bundle branch block, transvenous pacing is given a less stringent recommendation. Temporary transcutaneous pacing is recommended in every other scenario, with the exception of normal AV nodal and intraventricular conduction, isolated first-degree AV block, isolated left anterior or posterior fascicular block, and isolated old bundle branch block (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

1. Observe: continued ECG monitoring, no further action planned.

2. A, and A*: atropine administered at 0.6 to 1.0 mg IV every 5 minutes to up to 0.04 mg/kg. In general, because the increase in sinus rate with atropine is unpredictable, this is to be avoided unless there is symptomatic bradycardia that will likely respond to a vagolytic agent, such as sinus bradycardia or Mobitz I, as denoted by the asterisk above.

3. TC: application of transcutaneous pads and standby transcutaneous pacing with no further progression to transvenous pacing imminently planned.

4. TV: temporary transvenous pacing. It is assumed, but not specified in the table, that at the discretion of the clinician, transcutaneous pads will be applied and standby transcutaneous pacing will be in effect as the patient is transferred to the fluoroscopy unit for temporary transvenous pacing.

From Epstein et al: Circulation 2008;117:e350-408.

The culprit artery has prognostic implications. Complete heart block complicating anterior wall myocardial infarction—usually involving the proximal left anterior descending artery—is due to necrosis of the interventricular septum and irreversible damage to the His-Purkinje conduction system. In contrast, complete heart block in inferior wall infarction—usually involving the proximal right coronary artery (RCA)—is vagally mediated and atropine sensitive in the first hours of infarction.44 Local accumulation of adenosine in the days after infarction may lead to persistent, atropine-insensitive AV block, but permanent pacing is rarely indicated.45 Because the RCA supplies the SA nodal artery in 90% of cases, a proximal RCA infarction may also be complicated by sinus bradycardia, SA exit block, and sinus arrest; these, too, are typically transient in nature and atropine responsive.

Torsades de Pointes

The most important considerations in the management of torsades de pointes are appropriate recognition of the problem, correction of the underlying cause(s), and avoidance of QT-prolonging drugs that can further exacerbate the problem. Although this arrhythmia is polymorphic by definition, not all polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias are due to torsades de pointes. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia may complicate acute coronary syndrome, but it is typically associated with a suggestive clinical history and ST-segment deviation. Temporary or permanent pacemaker malfunction with ventricular undersensing can lead to “R on T” pacing, and certain pacemaker settings that minimize ventricular pacing can predispose to “long-short” sequences and polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias as well.46–49 If ventricular tachycardia is reliably initiated with pacing, pacemaker reprogramming may resolve the problem; electrophysiology consultation should be sought immediately.

The administration of magnesium sulfate (1-2 g over 5-10 minutes) is acutely effective in most patients.50 If ineffective, isoproterenol (1-4 µg/minute) can accelerate the heart rate and thereby shorten the QT, but this should be avoided in long QT syndrome—particularly long QT type 1—because of the potential for proarrhythmia.

Temporary pacing is indicated in patients who fail electrolyte supplementation and pharmacologic augmentation of the heart rate, or patients with severe AV conduction disturbances. Temporary pacing shortens the action potential and QT interval but also truncates the progressive, post-PVC (premature ventricular contraction) pauses that typically trigger an episode (see Fig. 5.2).51 Typically, pacing at a rate of 90 to 100 beats per minute is sufficient to suppress ventricular ectopy, but rates as fast as 140 beats per minute may be necessary.52 Patients with preexisting cardiac devices can be adjusted at the bedside to achieve the same effect. In patients with normal AV nodal conduction, atrial pacing is preferred.

Conditions That Do Not Normally Require Pacing

Hypothermia

Hypothermia can produce dramatic electrocardiographic abnormalities—PR prolongation, QRS widening, and QT prolongation, in addition to both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias—and familiarity with this condition is increasingly important in the critical care setting owing to the widespread adoption of therapeutic hypothermia in survivors of cardiac arrest.53,54 Moderate (32° C to 33.9° C) hypothermia causes a reduction in cardiac output that is mediated by sinus bradycardia, but this is accompanied by an increase in myocardial contractility and proportional decrease in basal metabolism. No specific treatment is needed, and attempts to increase the heart rate with drug or temporary pacing are counterproductive.55 Deep hypothermia (<30° C) is associated with increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, reduced responsiveness to electrical and pharmacologic cardioversion, and increased sensitivity to mechanical manipulation.56 One case report describes the successful resuscitation of two severely hypothermic patients with transcutaneous pacing,57 and another describes the near immediate initiation of ventricular fibrillation with transvenous pacing.58 The role of temporary pacing—whether transcutaneous or transvenous—is limited, and should be reserved for extreme situations of hemodynamic and electrical instability. The primary treatment is rewarming.

Hypothyroidism

Severe hypothyroidism is most commonly seen in the elderly and is most often precipitated by infections. Case reports have established that severe hypothyroidism and myxedema coma can cause a range of AV conduction abnormalities, including complete heart block. The symptoms of hypothyroidism can be vague, and the electrocardiographic manifestations—P wave flattening, low QRS voltage and intraventricular conduction delays, QT prolongation, and T wave flattening or inversion—are nonspecific. Thyroid hormone replacement can quickly normalize conduction but may take up to several weeks in some patients.59–61 Patients who present with new conduction abnormalities—particularly the elderly and infirm—should be routinely screened for hypothyroidism. Temporary pacing may be needed in cases of advanced AV block, but thyroid hormone supplementation is usually curative.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea has been associated with cyclic patterns of SA and AV nodal conduction disturbances, occasionally resulting in prolonged periods of asystole during sleep.62 In general, nocturnal arrhythmias are less clinically relevant than those during the day, and the need for intervention should be taken in the context of the clinical situation. Atropine has been shown to abolish cyclic variation and nocturnal bradycardia, suggesting that autonomic influences play a role.63 One study suggested that atrial overdrive pacing reduces the number of central and obstructive apneic episodes,64 but subsequent studies have shown no benefit and pacing does not have a role in the chronic management of this disorder.65–67 Continuous positive airway pressure abolishes conduction disturbances in the majority of patients, suggesting that hypoxia plays a role in the pathophysiology of the condition. It is the therapy of choice.68

Preoperative Anesthesia

Preexisting His-Purkinje disease—complete right or left bundle branch block, or bifascicular block, for example—does not routinely require temporary pacing before surgery. Patients with complete heart block with junctional, and particularly ventricular escape complexes, should be considered for temporary pacing due to the potentially suppressive effects of general anesthesia. Patients with underlying left bundle branch block who require Swan-Ganz catheterization have a small risk of procedurally related complete heart block due to catheter-induced right bundle branch block.69 In these situations, right-sided heart catheterization should be performed under fluoroscopy, and transcutaneous pacing should be immediately available. The presence of an “rS” complex in lead V1 may reflect left-to-right septal activation and left bundle branch delay, rather than complete left bundle branch block; the risk of catheter-induced heart block may be lower in these circumstances.70

Seizure

Severe sinus bradycardia and prolonged periods of asystole complicate less than 0.4% of seizures.71 “Ictal bradycardia” is felt to be vagally mediated, but there is disagreement in the epilepsy community about its potential contribution to sudden death.72,73 Although the majority of episodes terminate spontaneously, some patients are ultimately referred for pacemaker implantation. In the critical care setting, continuous electrocardiographic and encephalographic monitoring can be quite helpful if clinical features suggest prodromal seizure activity. The most appropriate management—including the potential need for temporary pacing—is unclear.

Spinal Cord Injury and Tracheal Suctioning

Severe cervical injury is nearly universally associated with sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, and hypotension in the days after injury, but these changes typically resolve within 2 to 6 weeks.74 Endotracheal intubation, tracheal suctioning, and repositioning can precipitate prolonged, vagally mediated pauses in these patients, presumably due to impairment of the sympathetic nervous system input during periods of increased parasympathetic tone. There have been case reports of asystolic cardiac arrest during tracheal suctioning, but supplemental oxygen therapy was at least partially effective in preventing further episodes, suggesting that hypoxia played a role.75 The administration of atropine, theophylline, aminophylline, and isoproterenol—individually, or in combination—may attenuate these pauses, but their administration may be ineffective in the short-term and cumbersome in the long-term. There is no consensus on the issue, but some authors advocate placement of a permanent pacemaker in patients with a prolonged requirement of mechanical ventilation, due to the unpredictable nature of these events.76 Temporary pacing can be considered on a case-by-case basis, but it is important to recognize that the primary underlying problem is autonomic in nature.

Esophageal and Transthoracic Pacing

The esophagus lies immediately posterior to the left atrium, and an esophageal pill electrode was historically used to record atrial activity. Esophageal recording makes it very easy to identify atrial activity, which can be useful in the differentiation of ventricular tachycardia and supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction.77 The presence of AV dissociation is virtually pathognomonic for ventricular tachycardia, but atrial activity is often difficult to recognize on the 12-lead electrocardiogram, particularly with fast, wide complex arrhythmias. Nevertheless, there are easy-to-use algorithms that allow for the rapid and relatively accurate diagnosis of wide complex rhythms, often regardless of whether atrial activity is apparent on the 12-lead electrocardiogram.78,79

Transcutaneous Pacing

Background

First described by Zoll in 1952 in the management of Stokes-Adams attacks, transcutaneous pacing involves the delivery of pacing stimuli though cutaneous patch electrodes.80 It is the fastest and technically least challenging means of temporary pacing, and it does not introduce the risks associated with vascular access and transvenous pacing. The initial system required the subcutaneous insertion of 21-gauge needles and was limited by high pacing thresholds and significant pain. The technology has evolved over time, but these issues remain to some degree. Capture is still unsuccessful in a significant minority of patients, and it can be difficult to assess capture because of saturation artifact from pacing stimuli—particularly if pacing outputs are high (Fig. 5.6).81 Transcutaneous pacing is still painful and generally requires the administration of sedation or analgesics. It is best tolerated in deeply anesthetized or unconscious patients, and most appropriate in situations in which pacing is required only briefly or intermittently, or as a bridging measure for placement of a transvenous system.

Methods

Commercially available external defibrillators have both pacing and defibrillating capability. The skin should be cleaned thoroughly with alcohol, but preferably not shaved, because the pain associated with pacing is typically localized to small abrasions and local salt deposits on the skin.82 The patch electrodes should be arranged in an anteroposterior position with one patch over the mid-dorsal spine at the left paravertebral position, and the other over the point of maximal impulse. If abrasions are present, the patches can be positioned in an adjacent area with intact skin. The external generator should be turned on at the lowest pacing output, and then increased in a step-wise fashion until reliable capture is observed on telemetry. It can be difficult to distinguish pacing artifact from capture, but the presence of a QRS complex and T wave—which represents cardiac depolarization and repolarization—is confirmatory. Capture should also be confirmed by the presence of a palpable or measurable pulse that matches the paced rate. The pacing outputs should be set just above capture threshold to minimize pacing artifact, pain, and risk of proarrhythmia.

Capture thresholds are predictably higher than with endocardial pacing, but most patients will capture at a pacing output of 40 to 70 mA. The capture threshold is proportional to the size of the patch electrode because of a reduction in current density—that is, larger electrodes require higher output for capture.83 Higher impedance electrodes are preferred for pacing, but standard patch electrodes are more practical in daily practice. Hypoxia, acidosis, and prolonged periods of asystole may increase the pacing threshold.84

Epicardial Pacing

Background

Permanent pacing is required in roughly 2% of coronary artery bypass grafting and up to 7.7% of valve surgery cases,85–87 but transient SND, fascicular block, bundle branch block, and AV block are common within the first few days following surgery.88 Epicardial pacing offers a safe and well-tolerated “bridge” to recovery, avoiding the need for transcutaneous and transvenous pacing. It also allows for prevention, diagnosis, and management of postoperative atrial arrhythmias, and the optimization of hemodynamics in the critical care setting.

Methods

Epicardial wires are typically placed on the anterior right atrium and right ventricle at the conclusion of open heart surgery, then threaded through the right and left subcostal areas for attachment to an external pulse generator. Most surgeons will routinely implant both atrial and ventricular leads because AV synchrony and native conduction is preferred whenever possible, particularly in patients with preexisting systolic dysfunction.89,90

Pacing and sensing thresholds typically deteriorate rapidly over 3 to 5 days owing to local inflammation, and should be checked on a daily basis to ensure adequate safety margins, particularly in patients with ongoing pacemaker dependency. External pulse generators can deliver impulses up to 20 mA, but high outputs may only further exacerbate the local inflammation that produces high pacing thresholds.91 Alternate locations—including the basal and lateral left ventricle—may be associated with more favorable pacing thresholds and cardiac performance.92

Prevention of Atrial Arrhythmias

Atrial fibrillation complicates 20% to 50% of cardiac surgery cases, resulting in longer times in the hospital, increased hospital costs, and higher morbidity and mortality rates.93 The administration of β-adrenergic blockers and amiodarone constitutes first-line therapy, but there is some data to support the use of atrial pacing in the postoperative setting.94,95 One small, prospective study demonstrated a 17% absolute risk reduction of postoperative atrial fibrillation through the use of “overdrive” atrial pacing (AAI mode at a minimum of 80 beats per minute) for 24 hours on the second postoperative day, but longer-term follow-up was not reported in the study.96 The trials have been small and heterogeneous in design, but meta-analysis suggests an absolute reduction of 10% of postoperative atrial fibrillation with overdrive atrial pacing.97

Diagnosis of Wide Complex Arrhythmias

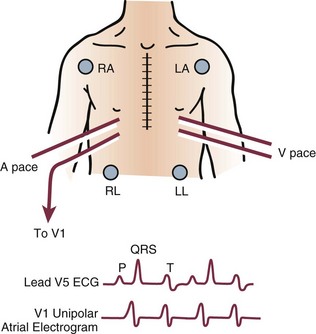

Atrial activity can be directly recorded by connecting the pin of the atrial wire to precordial lead V1 of the 12-lead electrocardiogram, elucidating the mechanism of a tachycardia (Fig. 5.7).

Risks

Some centers argue against the routine placement of epicardial wires because of their cost and potential risk, but their use remains nearly ubiquitous. The frequency of complications is far less than 1%, but case reports have described the inadvertent laceration of saphenous vein grafts,98,99 right atrium,100 and right ventricular outflow tract101 with development of either pericardial tamponade or hemothorax following their removal, and infection attributed to abandonment and bacterial colonization of the wires.102,103 Epicardial wires are almost always removed with gentle traction, and the prevailing thought is that their occasional abandonment does not constitute a risk to the patient. To minimize risk, they should be pulled after discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in a monitored setting.

Transvenous Pacing

Background

Cardiac pacing with an endocardial electrode was first introduced in 1959 and quickly supplanted transcutaneous pacing as the method of choice for temporary pacing.104 Transvenous pacing is more reliable and more comfortable than transcutaneous pacing, but it also takes longer to initiate and introduces some degree of procedural risk.

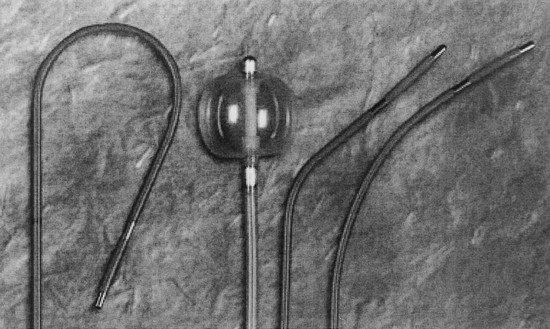

Methods

The internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral vein can be used, but the internal jugular is generally the preferred approach. The subclavian vein should be preserved for a permanent device, and the femoral vein carries a higher risk of infection, impedes patient movement, and requires fluoroscopic guidance. A variety of catheters are commercially available, the selection of which depends on operator preference, patient characteristics, and the availability of fluoroscopy (Fig. 5.8). Fluoroscopic imaging should be used routinely in patients with significant tricuspid regurgitation owing to the potential difficulty of catheter advancement across the tricuspid annulus in this setting. Fluoroscopic guidance should also be considered in patients with preexisting left bundle branch block and intermittent heart block due to the potential for catheter-induced complete heart block.

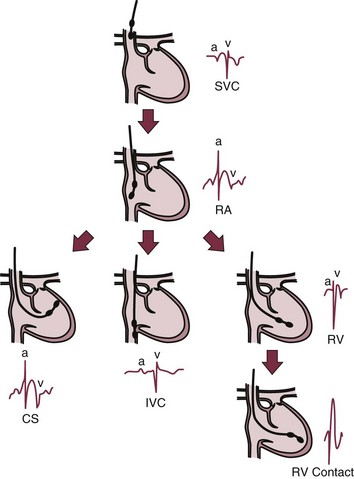

Fluoroscopy simplifies catheter placement, but it may be unavailable, or a patient may simply be too unstable to transport to the catheterization laboratory in the critical care setting. If portable fluoroscopy is unavailable, the procedure is best performed “blindly” at the bedside using a “floppy,” balloon-tipped catheter. Placement can be facilitated by electrocardiographic guidance, with or without pacing. If positioning is performed with pacing, the pacing catheter should be attached to an external pulse generator and set to pace at a rate slighter faster than the patient’s intrinsic rate and at an intermediate pacing output (5 mA) to ensure capture. Catheter contact and position can be assessed by examination of the paced QRS morphologic appearance: an “LBBB” morphologic pattern with positive QRS complexes in leads II, III, and aVF (inferior frontal axis) suggests catheter position in the right ventricular outflow tract (Fig. 5.9) whereas an “LBBB” morphologic pattern with negative QRS complex in leads II, III, and aVF (superior frontal axis) suggests catheter position in the right ventricular apex (Fig. 5.10). If in the outflow tract, gentle withdrawal of the catheter will allow it to fall to a more inferior position and further advancement will guide it toward the apex. Deflating the balloon, then very gently advancing the catheter an additional 1 to 2 mm to wedge it in between the trabeculae of the right ventricle, can improve catheter stability. If positioning is performed without pacing, a pattern of ST-segment elevation on the local electrocardiogram indicates endocardial contact (Fig. 5.11).105 The latter technique may be preferable in patients with complete heart block because even a brief period of overdrive pacing can extinguish a ventricular escape rhythm, resulting in immediate pacemaker dependency; therefore, transcutaneous pacing patches should be in place and available for use. If the pacing catheter has been advanced more than 40 cm without evidence of capture, it may have looped within the right atrium, or passed through the right atrium into the inferior vena cava. Either way, the catheter should be withdrawn with the balloon deflated, and then advanced again.

Special Considerations in Temporary Pacing

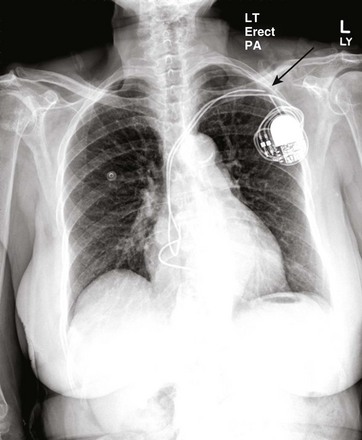

Contraindications

Transvenous pacing should not be attempted in patients with a known superior vena cava (SVC) stenosis, and any resistance encountered during advancement of an intracardiac catheter should prompt the use of fluoroscopy (Fig. 5.12). Similarly, the presence of a mechanical tricuspid valve is an absolute contraindication, due to the potential for irreversible catheter entrapment.106 Patients with any significant coagulopathy or ongoing need for anticoagulation may be better served with transcutaneous pacing, if at all possible. If transvenous pacing is necessary, it should be performed under fluoroscopic guidance to minimize the risk of lead perforation. Femoral access may be preferable in these circumstances, particularly if the need for transvenous pacing is felt to be short-lived.

Sensitivity and Threshold Testing

Owing to the inherent instability of a balloon-tipped catheter, sensing and pacing thresholds must be checked at least on a daily basis. Failure to sense can result in inappropriate pacing and precipitate polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias in rare circumstances.107 Failure to capture in a pacemaker-dependent patient has obviously deleterious consequences, and it is imperative that the device be programmed with an adequate safety margin, typically two times the measured threshold. Failure to capture can be easily recognized on the 12-lead electrocardiogram or telemetry monitor by the presence of pacing artifact without a subsequent QRS complex or T wave (Fig. 5.13). Failure to sense can be easily recognized by the indiscriminate delivery of pacing artifact, regardless of the underlying rhythm (Fig. 5.14).

Timing of Reimplantation

The timing depends on a number of factors, including (1) the stability of the temporary pacing system; (2) the pacing indication; and (3) ongoing contraindications to permanent implantation. In some circumstances—for example, in the setting of fungemia or endocarditis—a prolonged period of transvenous pacing is required. Permanent, “active fixation” pacing leads with retractable screws can be inserted through a peel-away venous sheath, and then attached to a permanent pulse generator on the patient’s skin. In patients with recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias, a permanent defibrillator lead can be attached to an externalized defibrillator in the same fashion.108 Permanent leads are more maneuverable than temporary leads, and the use of preformed stylets can facilitate delivery of the lead into the right atrium, if atrial pacing is desired. If AV synchrony is desired and SN function is normal, a VDD lead with atrial sensing and ventricular pacing capability can be placed.109 In day-to-day clinical practice, dual-chamber and biventricular pacing with temporary pacing catheters is rarely, if ever, performed.

Complications of Permanent Pacemaker Implantation

The most common complications following pacemaker implantation include bleeding, lead failure, and pneumothorax.110 Higher complication rates are noted with less experienced operators.110,111 Elderly patients (≥75 years) are also at increased risk of early postoperative complications.112 Body mass index, congestive heart failure, use of anticoagulants, and passive atrial fixation leads are also independent predictors for development of short-term (within 2 months) pacemaker complications.113

Lead Dislodgement

The incidence of lead dislodgement noted in clinical trials is 1.8% to 2.6%.4,114,115 Lead dislodgement rates depend on multiple factors and include lead fixation mechanism and operator experience. Active fixation (or “screw in”) mechanisms have reduced the frequency of this complication. Atrial leads may have higher rates of dislodgement than ventricular leads. Typically, lead dislodgement rates should be less than 3% with contemporary technology. Lead complications in general are more likely to occur with inexperienced operators.111

Lead dislodgement may lead to increased capture thresholds, loss of capture (see Fig. 5.13), or loss of sensing (see Fig. 5.14). When a change in lead position is detectable by chest radiograph, this is referred to as “macro-dislodgement.” However, loss of capture or undersensing can also be seen with “micro-dislodgement” of leads, where there is no detectable change in lead position on chest radiograph. In some cases of micro-dislodgement, intermittent undersensing of intrinsic complexes or a change in pacing threshold may be corrected by reprogramming the pacemaker sensitivity or output. However, large changes in lead position typically require lead revision. Intermittent motion of the cardiac lead may also result in increased ventricular ectopy, with a premature ventricular contraction morphologic pattern that is similar to the morphologic pattern of the paced complex.

Pneumothorax

Venous access may be obtained through subclavian or axillary puncture, as well as cephalic vein cut-down. Complications related to venous entry include bleeding, arterial injury due to inadvertent arterial puncture, pneumothorax, hemothorax, thrombosis, air embolism, arteriovenous fistula, and brachial plexus injury. The risk of pneumothorax related to subclavian venous puncture is 1% to 2%;4,114 this risk may be reduced with contrast venography.

Cardiac Perforation

Cardiac perforation has been reported to occur in less than 1% of patients undergoing permanent pacemaker implantation.114 The risk may be higher in elderly patients, particularly elderly women, or those requiring anticoagulation. Perforation may not be initially detected, as some patients are asymptomatic. Alternatively, patients may report chest pain or shortness of breath. Lightheadedness or syncope may also occur, and can be associated with hemodynamic compromise in patients who develop cardiac tamponade due to a large pericardial effusion.

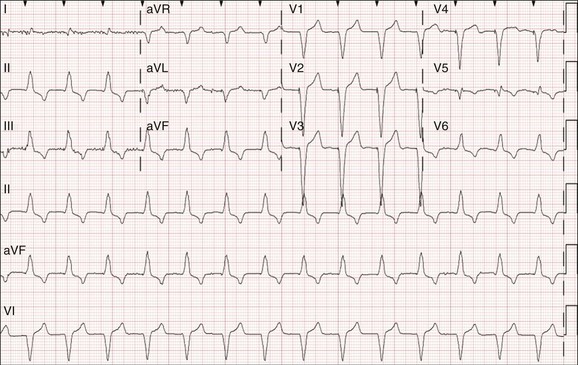

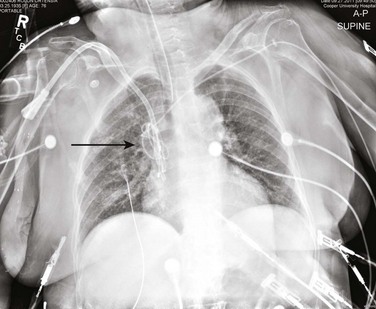

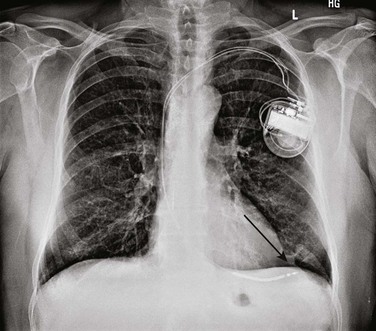

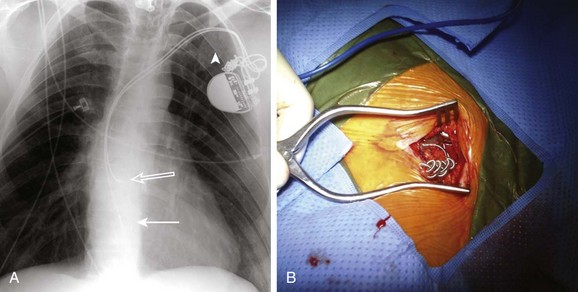

Signs of perforation may include pacemaker undersensing, increased pacemaker lead impedance, increased pacing threshold, loss of capture, or any combination thereof. Depending on the location of the perforation, diaphragmatic pacing or pericardial rub may also be noted. A change in the paced morphologic features from “LBBB” to “RBBB” in a patient with a single, right ventricular lead (Fig. 5.15A and B) is highly suggestive of a lead perforation and should be investigated further. Chest radiograph may show extension of the lead tip beyond the typical border of the right ventricle (Fig. 5.16). If loss of capture occurs in a pacemaker-dependent patient (Fig. 5.15C), higher pacing outputs may temporarily stabilize the situation, as long as the lead maintains some degree of contact with the ventricular myocardium. This is not a long-term solution but may obviate the need for transcutaneous or temporary transvenous pacing.

Bleeding and Hematoma

Hematoma is a common complication of pacemaker implantation, with increased risk in patients on anticoagulation. Although not life-threatening, a large hematoma can be quite painful, result in significant blood loss, and increase the risk of infection.116 In most cases, hematomas can be managed conservatively with observation and analgesia alone. Placing a pressure dressing over the site, immobilizing the ipsilateral arm in a sling, and temporarily withholding anticoagulation are often effective. However, in some cases, hematomas may become large and very painful, with oozing or drainage from the site (Fig. 5.17). When concomitant infection cannot be excluded, open wound exploration in a sterile setting should be considered. Needle aspiration of the hematoma should never be attempted at the bedside as this increases the risk of infection.

Precautions should be taken to reduce the risk of bleeding pre- and postoperatively. As with any surgical procedure, the risk of bleeding associated with device implantation must be weighed against the risk of interruption of anticoagulation. Official guidelines recommend “bridging” anticoagulation with heparin products in patients with mechanical valves, atrial fibrillation, and venous thromboembolic disease at “high” risk for thromboembolism.117 Nevertheless, there is a growing body of evidence in the electrophysiology literature that continuation of warfarin may be safer than “bridging” with unfractionated and low–molecular-weight heparin.118–120 There is no physician consensus about the optimal management of anticoagulation in this setting, but many physicians will implant pacemakers and defibrillators in fully anticoagulated patients.121 A patient with a compelling indication for anticoagulation may be better served by early initiation of warfarin, rather than a prolonged interruption of anticoagulation in the perioperative period. That being said, most operators will not implant if the international normalized ratio is in excess of 3.0. In addition, most physicians will not implant devices while patients are actively taking dabigatran (Pradaxa) or rivaroxaban (Xarelto); this may change with accumulated experience, but these agents should be withheld for five half-lives (roughly 48 hours) to minimize the risk of bleeding. Because there is significant variability in practice patterns, communication with the implanting physician about anticoagulation management is strongly recommended.

Patients who have undergone device implant should not receive unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin for at least 6 hours after completion of the procedure, and low-molecular-weight heparin should be avoided in patients with significant renal insufficiency.122 Dual antiplatelet therapy also increases the risk of pocket hematoma,123,124 but these agents are not commonly held.

Lead Failure

Lead failure is typically due to fracture or insulation break, and this typically occurs long after initial implantation. Lead damage most often occurs close to the puncture site in the infraclavicular region (Fig. 5.18). Damage to the insulation may also occur at a site beneath the pulse generator due to abrasion, or may be the result of a suture being placed directly on the lead itself, in lieu of a suture sleeve. External trauma may also lead to lead damage and fracture.

Twiddler’s Syndrome

Some patients may manipulate the pacemaker pulse generator, leading to dislodgement or fracture of the lead. This is called “twiddler’s syndrome.” Telemetry or electrocardiographic findings may include loss of capture and loss of sensing. In addition to demonstrating lead dislodgement, the twisted leads within the pacemaker pocket may also be visualized on chest radiograph (Fig. 5.19A). Suturing the pulse generator to the chest wall may help reduce motion of the pulse generator, although patients should always be instructed to avoid manipulation of the pocket. The operative appearance of the leads at the time of pacemaker lead revision is illustrated in Figure 5.19B.

Infection

Care should be taken to avoid implantation of a permanent pacemaker in a patient with active infection, as this will increase the risk for device infection. Any active infection is a relative contraindication to permanent pacemaker implantation, although active bacteremia or fungemia are absolute contraindications. A fever or rising leukocytosis within 24 hours of implant should delay device implantation until a thorough investigation can be performed. Temporary pacing is appropriate in this setting, although that, too, has been associated with an increased risk of infection.125 Patient characteristics also contribute to the risk of infection, and all modifiable risks should be optimized prior to device implantation.

Preoperative antibiotic administration has been shown to reduce the risk of device-related infection.116 There is no standard regimen, but most administer a penicillin or first- or second-generation cephalosporin for coverage of staphylococcus.126 Patients with a history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization or infection, recurrent or prolonged hospitalizations, or either a penicillin or cephalosporin allergy should be given vancomycin. Patients with a history of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) should be given either linezolid or daptomycin. There are limited data on the efficacy of postoperative antibiotic administration, but most implanting physicians empirically continue antibiotics for 24 hours after the procedure.

Careful attention to surgical technique and sterile procedures are important in preventing infection of the implanted pacemaker system. Pacemaker infection may be superficial or deep, with an incidence of less than 2% following initial implantation procedures, although it may be higher following generator replacement or lead revisions.4,127–129 Infections vary in severity from a superficial infection at the suture site with a local stitch abscess to a pocket infection or systemic infection with bacteremia. Erosion of the pacemaker pulse generator or leads may also be associated with infection.

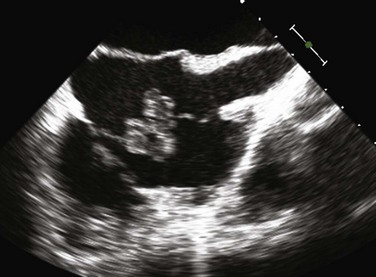

Superficial skin infections or stitch abscesses may be treated and cured with antibiotic therapy. However, lead-associated endocarditis is a more serious complication and is associated with a high mortality rate. Systemic infections with bacteremia and endocarditis require device and lead extraction. Vegetations may develop on the pacemaker lead itself and become large, requiring extraction and removal of the pacing system for cure (Fig. 5.20). Infections may occur many months after device implantation, and hematogenous spread of organisms from a distant site may be a contributing factor. The most common organisms responsible for cardiac implantable electronic device infections are S. aureus (often methicillin-resistant) and coagulase-negative staphylococci followed by streptococci, enterococci, and gram-negative rods.130,131

Special Considerations in Permanent Pacing

Magnet Application

Magnet application over a permanent pacemaker results in asynchronous pacing, such that pacing stimuli are delivered regardless of the underlying rhythm.132 Prolonged periods of asynchronous pacing should be avoided in the critical care setting, when concomitant metabolic and electrolyte derangement may increase the risk of proarrhythmia with “R on T” pacing. In contrast, a magnet placed over an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator suspends detection of ventricular arrhythmias, but it does not cause the device to pace asynchronously. In the critical care setting, magnet application over a permanent pacemaker can be used to confirm capture, evaluate the morphologic appearance of the paced complex, and terminate pacemaker-mediated tachycardia. In the defibrillator patient who experiences inappropriate shocks for rapidly conducted atrial fibrillation, lead fracture, or oversensing of physiologic signals, magnet application may be lifesaving.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The vast majority of implanted devices are not approved for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning due to the potential for lead heating, changes in pacing threshold, and cardiac stimulation with proarrhythmia. Current guidelines do not impose absolute contraindications against the use of MRI, but they do strongly recommend against its use in pacemaker-dependent patients and in patients with defibrillators, except in highly compelling circumstances.133 Based on expert opinion, patients with new implants (<6 weeks old), abandoned leads, passive leads, or epicardial leads, and pacemaker-dependent patients with defibrillators are ineligible for MRI, regardless of the clinical indication. Patients with temporary pacemakers are also ineligible, owing to similar concerns for lead heating and external interference.

If a patient with a cardiac device absolutely needs an MRI, close coordination with the electrophysiologist and radiologist is mandatory to minimize risk. The device should be programmed in an asynchronous mode with rate responsiveness and other special pacing features deactivated to minimize the likelihood of unwarranted pacing. Cardiac resuscitation equipment should be immediately available, and device interrogation should be repeated immediately after the scan.134 Within the last year, a new “MRI-compatible” pacemaker has become available for commercial use (Revo MRI SureScan, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). In selected patients with no alternative, lead and pulse generator extraction may be an option.135

References

1. Epstein, AE, DiMarco, JP, Ellenbogen, KA, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices); American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008; 117:e350–408.

2. Andersen, HR, Nielsen, JC, Thormsen, PE, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients from a randomized trial of atrial versus ventricular pacing for sick-sinus syndrome. Lancet. 1997; 350:1210–1216.

3. Nielsen, JC, Thomsen, PE, Hojberg, S, et al. A comparison of single-lead atrial pacing with dual-chamber pacing in sick sinus syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:686–696.

4. Lamas, GA, Lee, KL, Sweeney, MO, et al. Ventricular pacing or dual-chamber pacing for sinus-node dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1854–1862.

5. Mangrum, JM, DiMarco, JP. The evaluation and management of bradycardia. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:703–709.

6. Andersen, HR, Nielsen, JC, Thomsen, PE, et al. Atrioventricular conduction during long-term follow-up of patients with sick sinus syndrome. Circulation. 1998; 98:1315–1321.

7. Kristensen, L, Nielsen, JC, Pedersen, AK, et al. AV block and changes in pacing mode during long-term follow-up of 399 consecutive patients with sick sinus syndrome treated with an AAI/AAIR pacemaker. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001; 24:358–365.

8. Sutton, R, Kenny, RA. The natural history of sick sinus syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1986; 9:1110–1114.

9. Brandt, J, Anderson, H, Fahraeus, T, Schuller, H. Natural history of sinus node disease treated with atrial pacing in 213 patients: Implications for selection of stimulation mode. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992; 20:633–639.

10. Silver, MD, Goldschlager, N. Temporary transvenous cardiac pacing in the critical care setting. Chest. 1988; 93:607–613.

11. Jensen, G, Sigurd, B, Sandoe, E. Adams-Stokes seizures due to ventricular tachydysrhythmias in patients with heart block: Prevalence and problems of management. Chest. 1975; 67:43–48.

12. Lee, S, Wellens, HJJ, Josephson, ME. Paroxysmal atrioventricular block. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1229–1234.

13. Fisch, C, Greenspan, K, Edwards, RE. Complete atrioventricular block due to potassium. Circ Res. 1966; 19:373–377.

14. Schiraldi, F, Guiotto, G, Paladino, F. Hyperkalemia induced failure of pacemaker capture and sensing. Resuscitation. 2008; 79:161–164.

15. Ortega-Carniecer, J, Benezet, J, Benezet-Mazuecos, J. Hyperkalaemia causing loss of atrial capture and extremely wide QRS complex during DDD pacing. Resuscitation. 2004; 62:119–120.

16. Parham, WA, Mehdirad, AA, Biermann, KM, et al. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006; 33:40–47.

17. Martinez-Vea, A, Bardají, A, Garcia, C, et al. Severe hyperkalemia with minimal electrocardiographic manifestations: A report of seven cases. J Electrocardiol. 1999; 32:45–49.

18. Szerlip, HM, Weiss, J, Singer, I. Profound hyperkalemia without electrocardiographic manifestations. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986; 7:461–465.

19. Tiberti, G, Bana, G, Bossi, M. Complete atrioventricular block with unwidened QRS complex during hyperkalemia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998; 21:1480–1482.

20. Kim, NH, Oh, SK, Jeong, JW. Hyperkalaemia induced complete complex atrioventricular block with a narrow QRS. Heart. 2005; 91:e5.

21. Stewart, JSS, Steward, WK, Morgan, HG, et al. A clinical and experimental study of the electrocardiographic changes in extreme acidosis and cardiac arrest. Br Heart J. 1965; 27:490–497.

22. Guzman, SV, Deleon, AC, Jr., West, WJ, et al. Cardiac effects of isoproterenol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine in complete AV heart block during experimental acidosis and hyperkalemia. Circ Res. 1959; 7:666–672.

23. Zeltser, D, Justo, D, Halkin, A, et al. Drug-induced atrioventricular block: Prognosis after discontinuation of the culprit drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:105–108.

24. Vale, A. β blockers. Medicine. 1999; 27:27.

25. Love, JN, Sachdeva, DK, Curtis, LA, et al. A potential role for glucagon in the treatment of drug-induced symptomatic bradycardia. Chest. 1998; 114:323–326.

26. Zimmerman, JL. Poisonings and overdoses in the intensive care unit: General and specific management issues. Crit Care Med. 2003; 31:2794–2801.

27. Mahr, NC, Valdes, A, Lamas, G. Use of glucagon for acute intravenous diltiazem toxicity. Am J Cardiol. 1997; 79:1570–1571.

28. Papadopoulos, J, O’Neill, MG. Utilization of a glucagon infusion in the management of a massive nifedipine overdose. J Emerg Med. 2000; 18:453–455.

29. Hickey, AR, Wenger, TL, Carpenter, VP, et al. Digoxin immune Fab therapy in the management of digitalis intoxication: Safety and efficacy results of an observational surveillance study. J Am Coll Cardio. 1991; 17:590–598.

30. Reiffel, JA, Coromilas, J, Zimmerman, JM, et al. Drug-device interactions: Clinical considerations. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1985; 8:369–373.

31. Nadelman, RB, Wormser, GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557–565.

32. Naik, M, Kim, D, O’Brien, F. Lyme carditis. Circulation. 2008; 118:1881–1884.

33. Wormser, GP, Dattwyler, RJ, Shapiro, ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089–1134.

34. van der Linde, MR, Crijns, HJ, Lie, KI. Transient complete AV block in Lyme disease: Electrophysiologic observations. Chest. 1989; 96:219–221.

35. Mehta, NJ, Nehra, A. A 66-year-old-man with fever, hypotension, and complete heart block. Chest. 2001; 120:2053–2056.

36. Blumberg, EA, Karalis, DA, Chandrasekaran, K, et al. Endocarditis-associated paravalvular abscesses: Do clinical parameters predict the presence of abscess? Chest. 1995; 107:898–903.

37. Brecker, SJD, Pepper, JR, Eykyn, SJ. Aortic root abscess. Heart. 1999; 82:260–262.

38. Fordyce, CB, Leather, RA, Partlow, E, et al. Complete heart block associated with tricuspid valve endocarditis due to extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Can J Cardiol. 2011; 263:e17–20.

39. Kitkungvan, D, Suri, J, Spodick, D. Complete atrioventricular block: A rare presentation of mitral valve endocarditis. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010; 22:E1–2.

40. Bonow, RO, Carabello, BA, Chatterjee, K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006; 114:e84–e231.

41. Davidoff, R, Palacios, I, Southern, J, et al. Giant cell versus lymphocytic myocarditis. A comparison of their clinical features and long-term outcomes. Circulation. 1991; 83:953–961.

42. Antman, EM, Anbe, DT, Armstrong, PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction—Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). Circulation. 2004; 110:588–636.

43. Hindman, MC, Wagner, GS, JaRo, M, et al. The clinical significance of bundle branch block complicating acute myocardial infarction: Clinical characteristics, hospital mortality, and one-year follow-up. Circulation. 1978; 58:679–688.

44. Rosen, KM, Loeb, HS, Chuquimia, R, et al. Site of heart block in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1970; 42:925–933.

45. Zimetbaum, PJ, Josephson, ME. Use of the electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:933–940.

46. McLeod, AA, Jokhi, PP. Pacemaker induced ventricular fibrillation in coronary care units. BMJ. 2004; 328:1249–1250.

47. Vavasis, C, Slotwiner, DJ, Goldner, BG, et al. Frequent recurrent polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during sleep due to managed ventricular pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010; 33:641–644.

48. van Mechelen, R, Schoonderwoerd, R. Risk of managed ventricular pacing in a patient with heart block. Heart Rhythm. 2006; 3:1384–1385.

49. Pavri, B. Possible role of a common pacing algorithm in initiation of ventricular arrhythmia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32:663–666.

50. Tzivoni, S, Banai, C, Schuger, et al. Treatment of torsades de pointes with magnesium sulfate. Circulation. 1988; 77:392–397.

51. Rhoden, DM. A practical approach to torsades de pointes. Clin Cardiol. 1997; 20:285–290.

52. Viskin, S. Long QT syndromes and torsades de pointes. Lancet. 1999; 354:1625–1633.

53. Bernard, SA, Gray, TW, Buist, MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:557–563.

54. Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:549–556.

55. Polderman, KH, Herold, I. Therapeutic hypothermia and controlled normothermia in the intensive care unit: Practical considerations, side effects, and cooling methods. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:1101–1120.

56. Polderman, KH. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37(Suppl):S186–S202.

57. Ho, JD, Heegaard, WG, Brunette, DD. Successful transcutaneous pacing in 2 severely hypothermic patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49:678–681.

58. Towne, WD, Geiss, WP, Yanes, HO, et al. Intractable ventricular fibrillation associated with profound accidental hypothermia—Successful treatment with partial cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med. 1972; 30:1135–1136.

59. Zondek, H. The electrocardiogram in myxoedema. Br Heart J. 1964; 26:227–232.

60. Singh, JB, Starobin, OE, Guerrant, RL, et al. Reversible atrioventricular block in myxedema. Chest. 1973; 63:582–585.

61. Schoenmakers, N, de Graaff, WE, Peters, RHJ. Hypothyroidism as the cause of atrioventricular block in an elderly patient. Neth Heart J. 2008; 16:57–59.

62. Koehler, U, Fus, E, Grimm, W, et al. Heart block in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: Pathogenetic factors and effects of treatment. Eur Respir J. 1998; 11:434–439.

63. Guilleminault, C, Connolly, S, Winkle, R, et al. Cyclical variation of the heart rate in sleep apnoea syndrome: Mechanisms, and usefulness of 24 hour electrocardiography as a screening technique. Lancet. 1984; 1:126–131.

64. Garrigue, S, Bordier, P, Jais, P, et al. Benefit of atrial pacing in sleep apnea syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:404–412.

65. Simantirakis, EN, Schiza, SE, Chrysostomakis, SI, et al. Atrial overdrive pacing for the obstructive sleep apnea—Hypopnea syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2568–2577.

66. Unterberg, C, Luthje, C, Szych, J, et al. Atrial overdrive pacing compared to CPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:2568–2575.

67. Krahn, AD, Yee, R, Erickson, MK, et al. Physiologic pacing in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:379–383.

68. Harbison, J, O’Reilly, P, McNicholas, WT. Cardiac rhythm disturbances in the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2000; 118:591–595.

69. Stein, PD, Mahur, VS, Herman, MV, et al. Complete heart block induced during cardiac catheterization of patients with pre-existent bundle branch block. The hazard of bilateral bundle-branch block. Circulation. 1966; 34:783–791.

70. Padanilam, BJ, Morris, KE, Olson, JA, et al. The surface electrocardiogram predicts risk of heart block during right heart catheterization in patients with preexisting left bundle branch block: Implications for the definition of complete left bundle branch block. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010; 21:781–785.

71. Lanz, M, Oehl, B, Brandt, A, et al. Seizure induced cardiac asystole in epilepsy patients undergoing long term video-EEG monitoring. Seizure. 2011; 20:167–172.

72. Schuele, SU, Bermeo, AC, Locatelli, E, et al. Ictal asystole: A benign condition? Epilepsia. 2008; 49:168–171.

73. Strzelczyk, A, Cenusa, M, Bauer, S, et al. Management and long-term outcome in patients presenting with ictal asystole or bradycardia. Epilepsia. 2011; 52:1160–1167.

74. Lehmann, KG, Lane, JG, Piepmeir, JM, et al. Cardiovascular abnormalities accompanying acute spinal cord injury in humans: Incidence, time course and severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987; 10:46–52.

75. Mathias, CJ. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest during tracheal suction—Mechanisms in tetraplegic patients. Eur J Intensive Care Med. 1976; 2:147–156.

76. Franga, DL, Hawkins, ML, Medeiros, RS, et al. Recurrent asystole resulting from high cervical spinal cord injuries. Am Surg. 2006; 72:525–529.

77. Shaw, M, Niemann, JT, Haskell, RJ, et al. Esophageal electrocardiography in acute cardiac care. Efficacy and diagnostic value of a new technique. Am J Med. 1987; 82:689–696.

78. Brugada, P, Brugada, J, Mont. A new approach to the differential diagnosis of a regular tachycardia with a wide QRS complex. Circulation. 1991; 83:1649–1659.

79. Vereckei, A, Duray, G, Szénási, G. New algorithm using only lead aVR for differential diagnosis of wide QRS complex tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5:89–98.

80. Zoll, PM. Resuscitation of the heart in ventricular standstill by external electrical stimulation. N Engl J Med. 1952; 247:768–771.

81. Gould, BA, Marshall, AJ. Noninvasive temporary pacemakers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1988; 11:1331–1335.

82. Luck, JC, Markel, ML. Clinical applications of external pacing: A renaissance? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1991; 14:1299–1316.

83. Béland, MJ, Hesslein, PS, Finlay, CD. Noninvasive transcutaneous cardiac pacing in children. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1987; 10:1262–1270.

84. Zoll, PM, Zoll, RH, Falk, RH. External noninvasive temporary cardiac pacing: Clinical trials. Circulation. 1985; 71:937–944.

85. Pires, LA, Wagshal, AB, Lancey, R, et al. Arrhythmias and conduction disturbances after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Epidemiology, management, and prognosis. Am Heart J. 1995; 129:799.

86. Kim, MH, Deeb, GM, Eagle, KA, et al. Complete atrioventricular block after valvular heart surgery and the timing of pacemaker implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2001; 87:649–651.

87. Jaeger, FJ, Trohman, RG, Brener, S, et al. Permanent pacing following repeat cardiac valve surgery. Am J Cardiol. 1994; 74:505–507.

88. Baerman, JM, Kirsh, MM, de Buitleir, M. Natural history and determinants of conduction defects following coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987; 44:150–153.

89. Curtis, J, Walls, J, Boley, T, et al. Influence of atrioventricular synchrony on hemodynamics in patients with normal and low ejection fractions following open heart surgery. Am Surg. 1986; 52:93–96.

90. Curtis, JJ, Maloney, JD, Barnhorst, DA, et al. A critical look at temporary ventricular pacing following cardiac surgery. Surgery. 1977; 82:888–893.

91. Reade, MC. Temporary epicardial pacing after cardiac surgery: A practical review. Part 1: General considerations in the management of epicardial pacing. Anaesthesia. 2007; 62:264–271.

92. Hurle, A, Gomez-Plana, J, Sanchez, J, et al. Optimal location for temporary epicardial pacing leads following open heart surgery. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002; 25:1049–1052.

93. Echahidi, N, Pibarot, P, O’Hara, G, et al. Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:793–801.

94. Crystal, E, Garfinkle, MS, Connolly, SS, et al. Interventions for preventing post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004.

95. Mitchell, LB, Exner, DV, Wyse, DG, et al. Prophylactic oral amiodarone for the prevention of arrhythmias that begin early after revascularization, valve replacement, or repair: PAPABEAR: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005; 294:3093–3100.

96. Blommaert, D, Gonzalez, M, Mucumbitsi, J, et al. Effective prevention of atrial fibrillation by continuous atrial overdrive pacing after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1411–1415.

97. Burgess, DC, Kilborn, MJ, Keech, AC. Interventions for prevention of post-operative atrial fibrillation and its complications after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:2846–2857.

98. Mishra, PK, Lengyel, E, Lakshmanan, S, et al. Temporary epicardial pacing wire removal: Is it an innocuous procedure? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010; 11:854–856.

99. Price, C, Keenan, DJM. Injury to a saphenous vein graft during removal of a temporary epicardial pacing wire electrode. Br Heart J. 1989; 61:546–547.

100. Smith, JA, Tatoulis, J. Right atrial perforation by a temporary epicardial pacing wire. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990; 50:141–142.

101. Hoidal, CR. Pericardial tamponade after removal of an epicardial pacemaker wire. Crit Care Med. 1986; 14:305–306.

102. Lyons, C, Chaudhrey, M, O’Hern, J. An unusual complication of coronary bypass surgery. Clin Cardiol. 1986; 9:215–216.

103. Mansur, AJ, Grinberg, M, Costa, R, et al. Dura mater valve endocarditis related to retained fragment of postoperative temporary epicardial pacemaker lead. Am Heart J. 1984; 108:1049–1052.

104. Furman, S, Robinson, G. Use of an intracardiac pacemaker in the correction of total heart block. Surg Forum. 1958; 9:245–248.

105. Bing, OH, McDowell, JW, Hantman, J, et al. Pacemaker placement by electrocardiographic monitoring. N Engl J Med. 1972; 287:651.

106. Cooper, JP, Jayawickreme, SR, Swanton, RH. Permanent pacing in patients with tricuspid valve replacements. Br Heart J. 1995; 73:169–172.

107. McLeod, AA, Jokhi, PP. Pacemaker induced ventricular fibrillation in coronary care units. BMJ. 2004; 328:1249–1250.

108. Cooper, JM, Lavi, N, Polin, GM, et al. Temporary external implantable cardioverter defibrillator in the pacemaker-dependent ventricular tachycardia patient. Europace. 2011; 13:761–763.

109. Lepillier, A, Otmani, A, Waintraub, X, et al. Temporary transvenous VDD pacing as a bridge to permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with sepsis and haemodynamically significant atrioventricular block. Europace. 2012; 14:981–985.

110. Haug, B, Kjelsberg, K, Lapppegard, KT. Pacemaker implantation in small hospitals: Complication rates comparable to larger centers. Europace. 2011; 13:1580–1586.

111. Kirkfeldt, RE, Johansen, JB, Nohr, EA, et al. Risk factors for lead complications in cardiac pacing: A population-based cohort study of 28,860 Danish patients. Heart Rhythm. 2011; 8:1622–1628.

112. Armaganijan, LV, Toff, WD, Nielsen, JG, et al. Are elderly patients at increased risk of complications following pacemaker implantation? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012; 35:131–134.

113. Udo, EO, Zuithoff, PA, van Hemel, NM, et al. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: The FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:728–735.

114. Link, MS, Estes, NA, 3rd., Griffin, JJ, et al. Complications of dual chamber pacemaker implantation in the elderly. Pacemaker Selection in the Elderly (PASE). Investigators. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol. 1998; 2:175–179.

115. Connolly, SJ, Kerr, CR, Gent, M, et al. Effects of physiologic pacing versus ventricular pacing on the risk of stroke and death due to cardiovascular causes. Canadian Trial of Physiologic Pacing Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1385–1391.

116. de Oliveira, JC, Martinelli, M, Angelina, S, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis before the implantation of pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: Results of a large, prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009; 2:29–34.

117. Douketis, JD, Spyropoulos, AC, Spencer, FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. Chest. 2012; 141:326S–350S.

118. Ahmed, I, Gertner, E, Nelson, WB, et al. Continuing warfarin therapy is superior to interrupting warfarin with or without bridging anticoagulation therapy in patients undergoing pacemaker and defibrillator implantation. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7:745–749.

119. Cheng, A, Nazarian, S, Brinker, JA. Continuation of warfarin during pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: A randomized clinical trial. Heart Rhythm. 2011; 8:536–540.

120. Robinson, M, Healey, JS, Eikelboom, J, et al. Postoperative low-molecular-weight heparin bridging is associated with an increase in wound hematoma following surgery for pacemakers and implantable defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32:378–382.

121. Krahn, AD, Healey, JS, Simpson, CS, et al. Anticoagulation of patients on chronic warfarin undergoing arrhythmia device surgery: Wide variability of perioperative bridging in Canada. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1276–1279.

122. Michaud, GF, Pelosi, F, Jr., Noble, MD. A randomized trial comparing heparin initiation 6 hour or 24 hour after pacemaker or defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1915–1918.

123. Tompkins, C, Cheng, A, Dalal, D, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy and heparin “bridging” significantly increase the risk of bleeding complications after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2376–2382.

124. Wiegand, UKH, LeJeune, D, Boguschewski, F, et al. Pocket hematoma after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator: Influence of patient morbidity, operation strategy, and perioperative antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Chest. 2004; 126:1177–1186.

125. Klug, D, Balde, M, Pavin, D, et al. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 2007; 116:1349–1355.

126. Da Costa, A, Kirkorian G Cucherat, M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for permanent pacemaker implantation: A meta-analysis. Circulation. 1998; 97:1796–1801.

127. Greenspon, AJ, Patel, JD, Lau, E, et al. 16-year trends in the infection burden for pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the United States, 1993 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1001–1006.

128. Poole, JE, Gleva, MJ, Mela, T, et al. Complication rates associated with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacements and upgrade procedures: Results from the REPLACE registry. Circulation. 2010; 122:1553–1561.

129. Johansen, JB, Jorgensen, OD, Moller, M, et al. Infection after pacemaker implantation: Infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46,299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:991–998.

130. Greenspon, AJ, Rhim, ES, Mark, G, et al. Lead-associated endocarditis: The important role of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008; 31:548–553.

131. Tarakji, KG, Chan, EJ, Cantillon, DJ, et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device infections: Presentation, management, and patient outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7:1043–1047.

132. Jacob, S, Panaich, SS, Maheshwari, R, et al. Clinical applications of magnets on cardiac rhythm management devices. Europace. 2011; 13:1222–1230.

133. Levine, GN, Gomes, AS, Arai, AE, et al. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiovascular devices: An American Heart Association scientific statement from the Committee on Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiac Catheterization, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation. 2007; 116:2878–2891.

134. Nazarian, S, Halperin, HR. How to perform magnetic resonance imaging on patients with implantable cardiac arrhythmia devices. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:138–143.

135. Wilkoff, BL, Love, CJ, Byrd, CL, et al. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1085–1104.