CHAPTER 45 Carcinoma of the ovary and fallopian tube

Carcinoma of the Ovary

Epidemiology

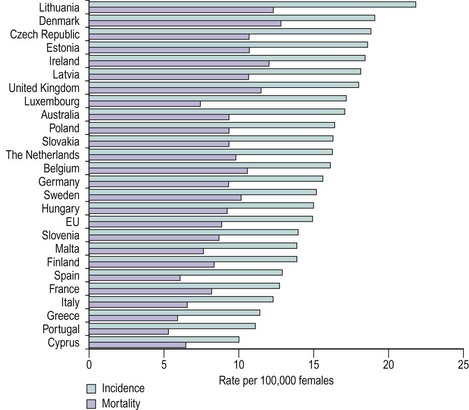

The incidence of ovarian carcinoma varies around the world, with lower rates recorded in Japan (3/100,000 women) and some of the highest rates recorded in the Nordic countries (20/100,000 women). Variations are also noted within Europe, with lower rates occurring in Mediterranean countries (Figure 45.1). In the UK, approximately 7000 cases are reported each year, with a mortality rate of 4500. As such, ovarian cancer remains the most lethal of the gynaecological cancers, and the fourth most common malignant cause of death in women. The majority of women present with disease spread outside the ovaries, normally stage III–IV disease (Table 45.1), and this has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 40%. Ovarian cancer is mainly a disease of postmenopausal women, with the bulk of cases occurring in women aged 50–75 years. The main histological tumours are epithelial in origin, accounting for 90% of cases. Serous tumours are the most common, and as tubal tumours are also serous, accurate identification of the true primary site of disease can be difficult.

| Stage I | Growth limited to the ovaries |

| Stage IA | Growth limited to one ovary, no ascites, no tumour on external surface, capsule intact |

| Stage IB | Growth limited to both ovaries, no ascites, no tumour on external surface, capsule intact |

| Stage IC | Tumour as for stage IA or B, but tumour on surface of one or both ovaries or capsule ruptured or positive ascites/peritoneal washings |

| Stage II | Tumour as for stage IC, but growth involving one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| Stage IIA | Extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes |

| Stage IIB | Extension to other pelvic tissue |

| Stage IIC | Tumour as for stage IIA or B, but tumour on surface of one or both ovaries or capsule ruptured or positive ascites/peritoneal washings |

| Stage III | Tumour involving one or both ovaries with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes. Includes superficial liver metastases or histologically proven malignant extension to small bowel/omentum |

| Stage IIIA | Tumour grossly limited to true pelvis with negative nodes, but histologically confirmed microscopic seeding of abdominal peritoneal surfaces |

| Stage IIIB | Tumour involving one or both ovaries with histologically confirmed implants of abdominal peritoneal surfaces, none exceeding 2 cm in diameter |

| Stage IIIC | Abdominal implants greater than 2 cm in diameter and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes |

| Stage IV | Growth of one or both ovaries with distant metastases, e.g. parenchymal liver metastases, or cytologically proven pleural effusion |

Aetiology

The main theory recounted for many years, called the ‘incessant ovulation theory’, is derived from the association between a woman’s number of lifetime ovulations and the risk of ovarian cancer. The greater the number of ovulations, the greater the risk of ovarian cancer. Prevention of ovulation by either pregnancy or use of the combined contraceptive pill should reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, and this has indeed been noted. Some of the proposed explanations for this theory are that the milieu of rapid cellular turnover (in the development of the ovum), the injury caused with release of the ovum and stromal invagination (which occurs at ovulation) contribute to the risk of malignancy. However, more complex factors are likely to be involved. For example, the progesterone in the contraceptive pill is known to cause apoptosis of ovarian cells, and this is being investigated in a phase II trial by the Gynecologic Oncology Group in high-risk patients to determine the apoptotic effect on ovarian tissues. This may potentially become a preventative therapy in the future.

Infertility

For many years, it has been recognized that there may be an association between infertility and risk of ovarian cancer. The relationship has never been absolutely clarified, and there are many conflicting reports in the literature (Mahdavi et al 2006, Jensen et al 2009). The difficulties mainly relate to the information available, as the types of drugs used, their duration of use and the outcome of pregnancies were not well recorded in many reports. One proposal associating the use of drug-induced ovulation and potential malignant transformation was seen in the increased ovarian cellular dyplasia in ovaries removed from women with a history of in-vitro fertilization treatment (Chene et al 2009). However, further larger longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the situation regarding infertility and ovarian cancer.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately one in eight women. The notable tumours associated with endometriosis are ovarian clear cell carcinomas. Endometrioid tumours are also known to have a relationship with endometriosis, but this association is weaker. An interesting fact is that clear cell tumours are most prevalent in Japan, despite the fact that Japan has the lowest incidence of ovarian cancer in the world. The concept that endometriosis is a premalignant condition has been proposed, based on the ability of endometriosis to metastasize, and also as it is found in association with ovarian malignancies. There is a need for further work in this area, but it is interesting to note that women with endometriosis also have a higher relative risk of developing other cancers (Melin et al 2007).

Molecular biology

One aspect of ovarian cancer is the somewhat limited understanding of the tumour biology and the natural history of the condition itself. Most patients present with advanced disease and it is often considered that ovarian cancer has a rapid growth phase, hence the late presentation with a short history of symptoms. Some work on symptoms in ovarian cancer suggests that these may be present some time prior to diagnosis (Goff et al 2007), and the natural progression of the disease may be different to previous assumptions. However, this requires further research before becoming acceptable.

In ovarian cancer, molecular markers have been researched although there is a lack of true understanding of tumour biology. Tumour vascular proteins (Buckanovich et al 2007) have been shown to have different expression in ovarian malignancies compared with normal, and with the development of antivascular endothelial growth factor therapies with a spectrum of tumour vascular proteins now recognized, further therapies may be developed. Serum mesothelin level is another marker noted to be elevated in ovarian cancer and to have a direct correlation with disease stage, and this could have potential use in screening (Huang et al 2006). Proteomic studies are used increasingly and should yield some valuable information to facilitate the understanding of ovarian cancer (Boyce and Kohn 2005).

Classification of ovarian tumours

The most commonly used classification of ovarian tumours was defined by the World Health Organization (Scully 1999). This is a morphological classification that attempts to relate the cell types and patterns of the tumour to tissues normally present in the ovary. The primary tumours are thus divided into those that are of epithelial type (implying an origin from surface epithelium and the adjacent ovarian stroma), those that are of sex cord gonadal type (also known as sex cord stromal type or sex cord mesenchymal type, and originating from sex cord mesenchymal elements) and those that are of germ cell type (originating from germ cells). A simplified classification is given in Table 45.2.

| Epithelial origin |

Pathology of epithelial tumours

Epithelial tumours are derived from the ovarian surface epithelium, which is a modified mesothelium with a similar origin and behaviour to the Müllerian duct epithelium, and from the adjacent distinctive ovarian stroma. They are subclassified according to epithelial cell type (serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear, transitional, squamous); the relative amount of epithelial and stromal component (when the stromal is larger than the cystic epithelial component, the suffix ‘fibroma’ is added); and the macroscopic appearance (solid, cystic, papillary). They account for 50–55% of all ovarian tumours, but their malignant forms represent approximately 90% of all ovarian cancers in the Western world (Koonings et al 1989). Well-differentiated epithelial carcinomas are more often associated with early-stage disease, but the degree of differentiation does correlate with survival, except in the most advanced stages. Diploid tumours tend to be associated with earlier stage disease and a better prognosis. Histological cell type is not in itself prognostically significant.

Endometrioid carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinomas are ovarian tumours that resemble the malignant neoplasia of epithelial, stromal and mixed origin that are found in the endometrium (Czernobilsky et al 1970). They account for 2–4% of all ovarian tumours. They are accompanied by ovarian or pelvic endometriosis in 11–42% of cases, and a transition to endometriotic epithelium can be seen in up to 30% of cases. The pathologist must distinguish metaplastic and reactive changes in endometriosis from true neoplastic changes.

Clear cell carcinoma

Clear cell carcinomas are the least common of the malignant epithelial tumours of the ovary, accounting for 5–10% of ovarian carcinomas (Anderson and Langley 1970).

Borderline epithelial tumours

Peritoneal lesions are present in some cases and although a few are true metastases, many do not grow and even regress after removal of the primary tumour. Surgical pathological stage and subclassification of extraovarian disease into invasive and non-invasive implants are the most important prognostic indicators for serous borderline tumours, with survival for advanced-stage serous tumours with non-invasive implants being 95.3% compared with 66% for tumours with invasive implants (Seidman and Kurman 2000).

Diagnosis

The symptoms associated with ovarian cancer have come under particular scrutiny over the last few years. The main symptoms are abdominal pain, bloating, postmenopausal bleeding, weight loss and loss of appetite (Bankhead et al 2005, Goff et al 2007). In approximately 10% of cases, there are no symptoms and the disease is found serendipitously, such as following a scan for back pain. Once there is a clinical suspicion of ovarian cancer, investigations can facilitate in defining the risk of malignancy, which will ensure the patient is referred appropriately. This is important as the expertise of the operator will influence the outcome and success of achieving tumour clearance (Junor et al 1999, Tingulstad et al 2003, Earle et al 2006).

The main primary investigations are serum CA125 and abdominal/pelvic ultrasound. These, in conjunction with the menopausal status of the patient, enable calculation of the risk of malignancy. Table 45.3 shows one form of calculation employed. Thus, a high risk of malignancy index (RMI) will capture most advanced ovarian cancers (Jacobs et al 1990). It must be remembered that not all ovarian cancers produce CA125, and mucinous cancers, in particular, can often have a normal CA125. Equally, a high RMI is not itself diagnostic, and the system is far from perfect. However, it is the only available mechanism at present to triage patients to appropriate specialist centres of care.

| RMI = Ultrasound score × Menopausal status × Serum CA125 Ultrasound score (U) Score one point for each of the following: Menopausal status |

| RMI | Risk of cancer (%) |

|---|---|

| <25 | <3 |

| 25–250 | 20 |

| >250 | 75 |

RMI, risk of malignancy index.

Surgery

In the 1970s, Griffiths published a paper relating survival in ovarian cancer to the amount of residual tumour left in the abdominal cavity. The original publication related to a retrospective series of just over 100 women, which indicated the preferable survival pattern in women with tumour residuum of less than 1.6 cm in diameter compared with those with great tumour loads. The premise for this was the report by Magrath et al (1974) on a similar finding with intra-abdominal Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A subsequent prospective study on 26 patients was published, some of whom had undergone primary surgery previously, and some who had also been exposed to chemotherapy (Griffiths et al 1979). Following aggressive surgery, the preferable survival pattern was associated with those who had the lesser tumour residuum. Thus, the optimum debulking procedure became embedded within clinical practice, and many subsequent reports have confirmed this association. Notably, no prospective randomized trials were ever performed to ascertain the validity of this approach, and debate continues about whether those amenable to optimum debulking are also those with the most chemosensitive tumours. Some meta-analyses have been published with variable results. Hunter et al (1992) reported on a cohort of over 6000 women with ovarian cancer, and concluded that the use of platinum agents rather than surgery was a more important factor in enhancing survival outcome. The more recent meta-analysis by Bristow et al (2002) associated the residuum of tumour with survival, and showed that each 10% increase in maximal cytoreductive surgery was associated with a 4.1% increase in median survival time. In Bristow et al’s study, unlike that of Hunter et al, all patients were exposed to platinum therapies. Of course, the strength of meta-analyses based on essentially large non-randomized series does permit some questioning of the weight of the final conclusions. Interestingly, a recent randomized trial of complete para-aortic and pelvic lymphadectomy in advanced ovarian cancer compared with excision of enlarged nodes alone did not reveal any survival benefit (Panici et al 2005).

An evidence base for practice is always welcome as this can at least attempt to ensure best practice and indeed facilitate patient counselling. Regarding primary surgical intervention, two trials have been undertaken, namely EORTC 55971 and CHORUS. These studies compared standard upfront surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy (six cycles) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (three cycles) then surgery and then a further three cycles of platinum. The EORTC study has only been reported at meetings; peer-reviewed publications are awaited. The CHORUS study is ongoing. These studies are the first randomized trials to address the primary interventions in ovarian cancer (www.eortc.be/protoc/listprot.asp, www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/studies/).

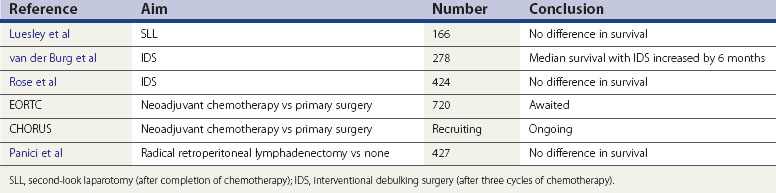

Interventional debulking surgery

When optimum debulking is not achieved at the primary operation, a second attempt may be worthwhile. With this objective, three prospective randomized trials were developed. The smallest trial (Redman et al 1994) was stopped prematurely as no advantage was noted at the interim analysis. In this study, optimum debulking was defined as less than 2 cm in diameter. The second study (van der Burg et al 1995) randomized over 300 women who had primary suboptimal surgery (>1 cm residuum) and were chemosensitive to platinum. Optimum in this study was defined as tumour less than 1 cm in diameter. The study showed a 6 month improvement in median survival in those having a second operation (performed after three of six cycles of platinum treatment). This was the first randomized study published supporting the concept of optimum debulking as a procedure influencing survival in ovarian cancer. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) (Rose et al 2004) published a similar trial which did not reveal any survival difference with interventional debulking surgery. The trials differed in a few aspects: firstly, paclitaxel was included in the GOG study (not available in van de Burg et al’s study), and secondly, more patients in the GOG study had primary surgery by trained gynaecological oncologists, thus influencing the primary optimum debulking rates. The conclusions are therefore conflicting: in European practice, interventional debulking surgery may have a role, but in present-day US practice, it does not seem to have a role if managed by gynaecological oncologists.

Second-look surgery

Second-look laparotomy (SLL) was introduced so that a thorough evaluation of tumour response was possible, and thus ongoing therapy could cease. This was during an era when therapy was continued for over 12 months, and it became evident that iatrogenic malignancies were developing with long-term treatment. The original SLL was performed after 12 months of cytotoxic therapy (Smith et al 1976). In present practice, there are many other non-invasive methods to determine tumour response, but SLL has remained part of routine practice in some countries. One randomized trial has been performed assessing the impact of SLL on survival outcome (Luesley et al 1988), and this did not reveal any benefit. As such, SLL should remain within the context of any relevant clinic trials, rather than part of routine care.

Surgery at relapse

With disease persisting after chemotherapy, or occurring within 6 months of completion of chemotherapy, such disease is deemed resistant and surgery has little role, other than palliation of symptoms. Outside this range, there may be a beneficial effect of further surgery. A series of retrospective studies have identified a group of women in whom surgery at relapse may prolong survival (Jänicke et al 1992, Zang et al 2004, Salani et al 2007). These patients had optimum debulking at primary surgery, a disease-free interval of 12 months and were less than 60 years of age. In this population, there was a greater chance of achieving optimum debulking at second surgery. The most comprehensive study (DESKTOP study) was a multinational study identifying predictive factors for complete tumour clearance in women presenting with relapsed ovarian cancer (Harter et al 2006). From this cohort of 267 women, a 79% prediction rate was achieved with the following variables: good performance status, original optimum debulking, early stage of disease at presentation and no ascites at relapse. In those who had complete resection at second surgery, median survival was 45.2 months compared with 19.7 months in those left with any visible disease. With good predictive models, individuals who may gain survival advantages with surgery at relapse can be identified and will require chemotherapy in conjunction with surgery. It is also well recognized that chemotherapy is more effective for longer disease-free intervals (Blackledge et al 1989); hence, tumour biology, not just surgery, may play an important role. Only a prospective trial will determine the true influence of surgery in this context.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is administered to nearly all women suffering from ovarian cancer. The ICON 1 study (Colombo et al 2003), comparing adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with observation in mainly early-stage disease, did note benefits, even in those with early-stage disease, but no benefit was seen for those with well to moderately differentiated epithelial tumours. It is important that disease staging is performed correctly, as in a cohort from a similar type study (ACTION), it was noted that survival was improved in those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy who were not appropriately staged but assumed to have early-stage disease (Trimbos et al 2003).

The mainstay of therapy remains platinum based, with paclitaxel used in combination in many countries. This would be deemed standard in some countries following a series of studies reporting a superior survival pattern with the addition of paclitaxel to platinum agents in first-line therapy studies (McGuire et al 1996, Piccart et al 2000, Ozols et al 2003). However, in the UK, where ICON 4 (Parmar et al 2003) did not show a benefit associated with the addition of palitaxel, the guidance of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2003) remains open in this regard.

Intraperitoneal therapy

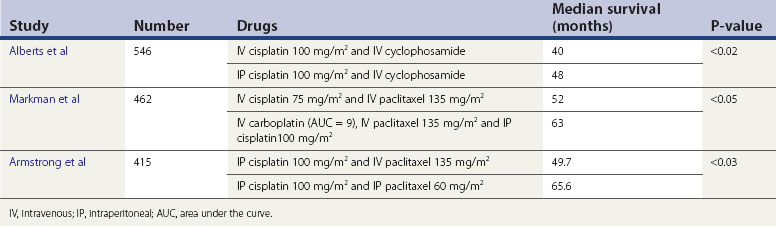

Some years ago, intraperitoneal therapy was used, in that cyclophosphamide was administered into the peritoneal cavity at surgery. Subsequently, it was recognized that to become active, cyclophosphamide required liver metabolism. Hence the practice ceased. Advocates of the possible survival benefits remained, and in 1996, Alberts et al reported on an randomized controlled trial whereby intraperitoneal cisplatin was given in conjunction with intravenous therapy, and the median survival was increased from 40 to 48 months. There were known side-effects and there was no general acceptance of this type of therapy, mainly due to this and the more complicated manner of administration of cytotoxics compared with intravenous access. However, two further trials (Markman et al 2001, Armstrong et al 2006) which incorporated paclitaxel into the therapy showed increased median survival rates of over 10 months in the intraperitoneal arm. There has been some debate about these trials, in particular that the overall doses employed in the control arms could be considered suboptimal compared with more modern doses, and thus impacting on the survival differences noted (Swart et al 2008).

The issue regarding toxicity also arises, although one study showed that neurotoxicity remained the only variable worse in patients treated with intraperitoneal therapy, compared with intravenous therapy, at 1 year after treatment (Wenzel et al 2007). The recent Cochrane review on this topic concludes that intraperitoneal therapy does afford better survival patterns, but this needs to be measured carefully against toxicity (Jaaback and Johnson 2006) (Table 45.4).

Novel approaches

The approaches to ovarian cancer care are beginning to change, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy increasingly reported (Steed et al 2006). However, the more exciting approaches relate to using a greater number of molecular targets, and indeed developing studies which are more tumour specific. There are ongoing studies for ovarian clear cell tumours, and a study for mucinous tumours is in development. The main molecular targets of therapy are poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, used in BRCA mutational tumours such as breast and ovarian cancer (Drew and Calvert 2008). Equally, the results of large trials on targeting vascular endothelial growth factor are awaited with interest, and should hopefully add another approach to therapy (Table 45.5).

Carcinoma of the Fallopian Tube

Fallopian tube malignancies are very rare, although notably there is increasing interest in the proposal that many ovarian serous carcinomas are actually primary fallopian tube carcinomas. However, by virtue of the disease extent at surgery, it is impossible to distinguish the primary source of the cancer. The finding that women with fallopian tube cancers have a 15.9% prevalence of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations or family histories of early-onset breast or ovarian cancer (Aziz et al 2001) also suggests that some advanced ‘ovarian’ cancers may actually have originated from the fallopian tubes. Supporting this possibility is the fact that microscopic fallopian tube cancers are found in women undergoing prophylactic surgery for ovarian cancer, indicating a possible hereditary factor (Hirst et al 2009).

Staging

The FIGO clinical staging for cancer of the fallopian tube is similar to that used for ovarian cancer. Probably because of the difficulty in distinguishing between advanced ovarian and advanced fallopian tube carcinoma, 74% of fallopian tube carcinomas are diagnosed at stage I–IIA, while the remaining 26% are diagnosed at stage IIB–IV (Hellström et al 1994).

Results

The overall 5-year survival rate for carcinoma of the fallopian tube is approximately 35%. The prognosis is improved if the tumour is detected at an early stage. The 5-year survival rate for stage I is in the region of 70%, as is that for stage IA cases. However, survival falls to 25–30% in stages IB–IIIC (Hellström et al 1994). Chemotherapy with platinum agents improves survival.

Conclusions

KEY POINTS

Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:1950-1955.

Anderson MC, Langley FA. Mesonephroid tumours of the ovary. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1970;23:210-218.

Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:34-43.

Aziz S, Kuperstein G, Rosen B, et al. A genetic epidemiological study of carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Gynecologic Oncology. 2001;80:341-345.

Bankhead CR, Kehoe ST, Austoker J. Symptoms associated with diagnosis of ovarian cancer: a systematic review. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:857-865.

Benedet JL, Sergio Pecorelli S, Ngan HYS, et al. Staging Classifications and Clinical Practice: Guidelines for Gynaecological Cancers. pp 95–117 www.figo.org/docs/staging_booklet.pdf, 2006.

Blackledge G, Lawton F, Redman C, Kelly K. Response of patients in phase II studies of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: implications for patient treatment and the design of phase II trials. British Journal of Cancer. 1989;59:650-653.

Boyce EA, Kohn EC. Ovarian cancer in the proteomics era: diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics targets. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2005;15(Suppl 3):266-273.

Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:1248-1259.

Bristow RE, Eisenhauer EL, Santillan A, Chi DS. Delaying the primary surgical effort for advanced ovarian cancer: a systematic review of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval cytoreduction. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007;104:480-490.

Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, et al. Tumor vascular proteins as biomarkers in ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:852-861.

Chene G, Penault-Liorca F, LeBoudedec G, et al. Ovarian epithelial dysplasia after ovulation induction: time and dose effect. Human Reproduction. 2009;24:132-138.

Czernobilsky B, Silverman BB, Mikuta JJ. Endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary. A clinicopathologic study of 75 cases. Cancer. 1970;26:1141-1152.

Colombo N, Guthrie D, Chiari S, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1: a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early-stage ovarian cancer. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm (ICON) collaborators. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:125-132.

Drew Y, Calvert H. The potential of PARP inhibitors in genetic breast and ovarian cancers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1138:136-145.

Earle CC, Schrag D, Neville BA, et al. Effect of surgeon specialty on processes of care and outcomes for ovarian cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:172-180.

Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109:221-227.

Griffiths CT. Surgical resection of tumor bulk in the primary treatment of ovarian carcinoma. National Cancer Institute Monograph. 1975;42:101-104.

Griffiths CT, Parker LM, Fuller AFJr. Role of cytoreductive surgical treatment in the management of advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer Treatment Reports. 1979;63:235-240.

Gynecologic Oncology Group. Phase II double blind randomized trial evaluating the biologic effect of levonorgestrel on the ovarian epithelium in women at high risk for ovarian cancer (IND# 79,610). http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/.

Harter P, Bois A, Hahmann M, et al. Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Committee; AGO Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2006;13:1702-1710.

Hellström A-C, Silfverswärd C, Nilsson B, Pettersson F. Carcinoma of the fallopian tube. A clinical and histopathological review. The Radiumhemmet series. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 1994;4:395-400.

Hirst JE, Gard GB, McIllroy K, Nevell D, Field M. High rates of occult fallopian tube cancer diagnosed at prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2009;19:826-829.

Hunter RW, Alexander ND, Soutter WP. Meta-analysis of surgery in advanced ovarian carcinoma: is maximum cytoreductive surgery an independent determinant of prognosis? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;166:504-511.

Huang CY, Cheng WF, Lee CN, et al. Serum mesothelin in epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a new screening marker and prognostic factor. Anticancer Research. 2006;26:4721-4728.

Jaaback K, Johnson N 2006 Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the initial management of primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD005340.

Jacobs I, Oram D, Fairbanks J, Turner J, Frost C, Grudzinskas JG. A risk of malignancy index incorporating CA 125, ultrasound and menopausal status for the accurate preoperative diagnosis of ovarian cancer. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:922-929.

Jänicke F, Hölscher M, Kuhn W, et al. Radical surgical procedure improves survival time in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:2129-2136.

Jensen A, Sharif H, Frederiksen K, Kjaer SK. Use of fertility drugs and risk of ovarian cancer: Danish population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2009;338:a3075.

Junor EJ, Hole DJ, McNulty L, Mason M, Young J. Specialist gynaecologists and survival outcome in ovarian cancer: a Scottish national study of 1866 patients. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:1130-1136.

Koonings PP, Campbell K, Mishell DR, Grimes DA. Relative frequency of primary ovarian neoplasms: a 10 year review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;74:921-926.

Luesley D, Lawton F, Blackledge G, et al. Failure of second-look laparotomy to influence survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. The Lancet. 1988;2:599-603.

Maggioni A, Benedetti Panici P, Dell’Anna T, et al. Randomised study of systematic lymphadenectomy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer macroscopically confined to the pelvis. British Journal of Cancer. 2006;95:699-704.

Mahdavi A, Pejovic T, Nezhat F. Induction ovulation and ovarian cancer: a critical review of the literature. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;85:819-826.

Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:1001-1007.

McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334:1-6.

Magrath IT, Lwanga S, Carswell W, Harrison N. Surgical reduction of tumour bulk in management of abdominal Burkitt’s lymphoma. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1974;2:308-312.

Melin A, Sparén P, Bergqvist A. The risk of cancer and the role of parity in women with endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:3021-3026.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the Use of Paclitaxel in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. NICE, London, 2003. http://www.nice.org.uk/pdf/55_Paclitaxel_ovarianreviewfullguidance.pdf.

Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:3194-3200.

Panici PB, Maggioni A, Hacker N, et al. Systematic aortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy versus resection of bulky nodes only in optimally debulked advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:560-566.

Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. The Lancet. 2003;361:2099-2106.

Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, et al. Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year results. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:699-708.

Redman CWE, Warwick J, Luesley DM, Varma R, Lawton FG, Blackledge GPR. Intervention debulking surgery in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101:142-146.

Rose PG, Nerenstone S, Brady MF, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for advanced ovarian carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:2489-2497.

Salani R, Santillan A, Zahurak ML, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized, recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: analysis of prognostic factors and survival outcome. Cancer. 2007;109:685-691.

Scully RE. WHO International Histological Classification of Tumor. Histologic Typing of Ovarian Tumours. Heidelberg: Springer; 1999.

Seidman JD, Kurman RJ. Ovarian serous borderline tumors: a critical review of the literature with emphasis on prognostic indicators. Human Pathology. 2000;31:539-556.

Smith JP, Delgado G, Rutledge F. Second-look operation in ovarian carcinoma: postchemotherapy. Cancer. 1976;38:1438-1442.

Steed H, Oza AM, Murphy J, et al. A retrospective analysis of neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy versus up-front surgery in advanced ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 1):47-53.

Swart AM, Burdett S, Ledermann J, Mook P, Parmar MK. Why i.p. therapy cannot yet be considered as a standard of care for the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19:688-695.

Tingulstad S, Skjeldestad FE, Hagen B. The effect of centralization of primary surgery on survival in ovarian cancer patients. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102:499-505.

Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. EORTC-ACTION collaborators. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:94-95.

van der Burg ME, van Lent M, Buyse M, et al. The effect of debulking surgery after induction chemotherapy on the prognosis in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecological Cancer Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:629-634.

Wenzel LB, Huang HQ, Armstrong DK, Walker JL, Cella D. Health-related quality of life during and after intraperitoneal versus intravenous chemotherapy for optimally debulked ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:437-443.

Zang RY, Li ZT, Tang J, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: who benefits? Cancer. 2004;100:1152-1161.