CHAPTER 84 Bursitis

INTRODUCTION

It is unlikely that the following discussion will do a great deal to alter the rather menial significance attributed to the bursae:

Ensuring the smooth and frictionless working of the body corporate, usually uncomplaining, inconspicuous, hard-working, and very modest in their requirements, the bursae have been so neglected that, even when one of them misbehaves, this is usually misattributed to some more important structure.30

Olecranon bursitis is the most commonly involved site followed by the bicipital radial bursa. The latter is particularly involved in partial ruptures of the biceps tendon insertion. The presence of these structures is even variable and is probably developmental, because not all bursae are present at birth.43

ANATOMY

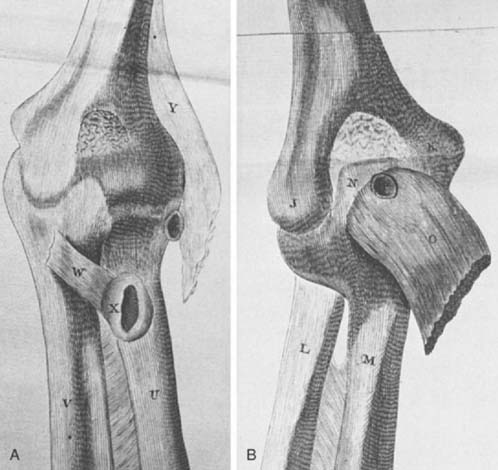

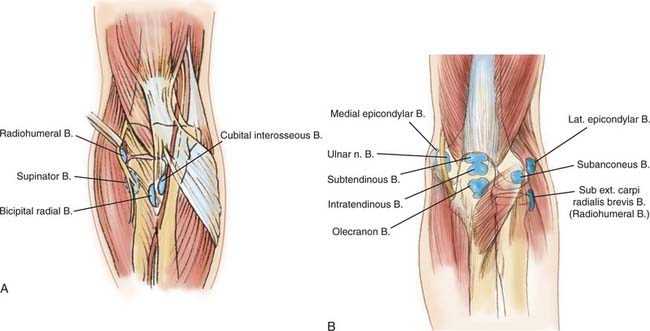

As early as 1788, Monro described several deep bursae about the elbow (Fig. 84-1). Through the years, additional bursae have been described. They may be divided into deep and superficial types (Fig. 84-2). Anatomically, the deep bursae are situated between muscles or between muscle and bone, which makes anatomic recognition somewhat difficult and clinical involvement almost impossible to diagnose. The superficial bursae consist only of those over the epicondyles and that over the olecranon, which is by far the most important one.

DEEP BURSAE

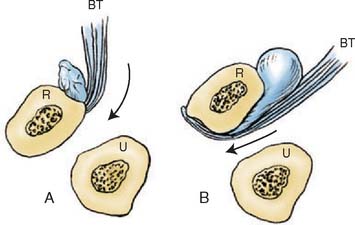

Pathologic involvement of any of the deep bursal structures is rather uncommon. This fact, coupled with the difficulty of identifying some of these structures by anatomic dissection, brings into question the very existence of certain structures. The most significant of the deep bursae is the bicipital radial bursa, which occurs at the radial tuberosity (Fig. 84-3). Owing to its anatomic site, inflammation of the bursa may occur with pronation and supination and can be confused with distal biceps tendinitis.20 Distinguishing between impending distal biceps tendon rupture and bicipital radial bursitis is not simple.1 In fact, one of the few cases of cubital bursitis reported by Karanjia and Stiles showed degeneration of the biceps tendon insertion.20 Crepitus on pronation and supination suggests impending rupture. Fullness or swelling of the cubital space that is accentuated on pronation is more consistent with bicipital radial bursitis.20 I have used selective lidocaine injections to help localize the lesion to the tuberosity, but this does not distinguish between the two processes. Usually the diagnosis is presumptive and the treatment is symptomatic–rest, ice or heat, and anti-inflammatory agents.

Tennis elbow and irritation of the radial nerve have been reported to result from inflammation of the radiohumeral bursa, which lies under the extensor carpi radialis brevis.5 Although bursitis was once thought to be a common cause of tennis elbow, according to our current understanding of lateral epicondylitis the association seems to be uncommon. Yet this structure does exist and has been demonstrated in anatomic dissections.30,31 I have had one patient who developed adventitial epicondylar bursitis after a common extensor tendon slide. Symptoms resolved after excision.

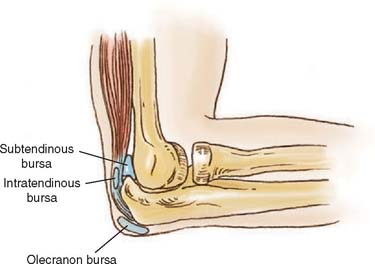

Deep bursae have been associated with the triceps tendon. The significance of the two deep bursae around the triceps (Fig. 84-4) is a matter of speculation, because no recognizable clinical presentation has been documented for these structures. It is possible that inflammation of either the intratendinous or subtendinous bursae could be mistaken for tendinitis or that of the subtendinous bursae for tendinitis, synovitis, or capsulitis. Idiopathic calcific involvement of the subtendinous bursae has been described.41 Yet calcification of bursae around the elbow is distinctly unusual, in contrast to calcific tendinitis in the region of the shoulder. Calcium appears to form in response to anoxia, which causes a cellular response with giant cell reaction. The result is an inflamed, “hot”-looking joint or bursa.

SUPERFICIAL BURSAE

The olecranon and the medial and lateral epicondylar bursae are the only superficial bursae about the elbow. I have occasionally observed an inflamed medial epicondylar bursa associated with chronic subluxation of the ulnar nerve. This probably rather uncommon lesion is treated by attending to the primary pathologic process involving the ulnar nerve. It is interesting to note that the olecranon bursa is not present at birth and has been shown to develop after the 7th year.6 This is consistent with others’ observations that bursae increase in size with age. Spontaneous rupture of the triceps tendon (see Chapter 35) may be related to tendon degeneration, as has been documented with disruptions of the insertion of the bicipital tendon.10 This process could masquerade as bursitis.

OLECRANON BURSITIS

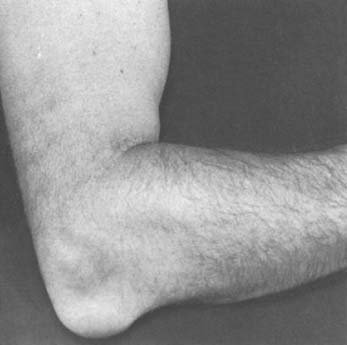

The olecranon is the site of the most common type of superficial bursitis.33 Olecranon bursitis is caused by a number of pathologic conditions that are traumatic (overuse or direct impact), inflammatory, infectious, or noninfectious. Since 1975, it has been associated with dialysis in the ipsilateral extremity.17 I have also observed olecranon bursitis after reconstructive procedures when a posterior approach was used (Fig. 84-5).

Inflammation of the superficial olecranon bursa can also result from direct trauma or repetitive stress, the so-called miner’s elbow or student’s elbow. Larson and Osternig have also shown that olecranon bursitis is a common football injury and is often associated with artificial turf.24

Involvement with systemic inflammatory processes such as rheumatoid arthritis,27 gout, chondrocalcinosis,12 or hydroxyapatite crystal deposition29 has been reported. Diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis has also been shown to give rise to olecranon synovitis,28 and xanthoma has been reported to involve this region.38 In lesions due to chronic overuse–for example, coal miner’s bursitis–the synovial cells that are least subject to mechanical stress have been shown to be those that elaborate the synovial fluid.26

The distinction between septic and aseptic olecranon bursitis can be somewhat difficult to make. About 20% of cases of acute bursitis have a septic cause.18,38 Distinguishing between a septic and an aseptic inflammatory bursitis has been the subject of a detailed study by Ho and Tice15 and is discussed in Chapter 68. Fever, tenderness, and parabursal cellulitis are common with septic bursitis; however, these findings are not specific, and a more detailed study by Smith and associates revealed that the skin over a septic bursa is almost 4°C warmer than that over the nonseptic contralateral extremity.37 The sepsis causes pain in approximately 80%, whereas nonseptic bursitis is tender in only about 20%. It should be noted that Gram stain results are positive in only about 50% of patients. Approximately 80% are caused by Staphylococcus aureus or another gram-positive organism.44 Particular care must be exercised in evaluating dialysis patients because they may present with a sterile inflammatory process but have pain and warmth that suggest an infection.17 The problem is compounded by the fact that about 20% of these patients are also found to have a septic process.19 The correct diagnosis is suggested when aspirate from the bursa demonstrates a high leukocyte count. Thus, a presumptive diagnosis can usually be made before the culture results have been obtained. Contiguous spread of septic olecranon bursitis leading to osteomyelitis of the olecranon has been thought to be possible, although it is probably rare. Excision of the olecranon has been recommended to avoid this possibility.25

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A distended olecranon bursa is usually painless unless it is associated with a septic or crystalline inflammatory process. The two inflammatory conditions most frequently associated with olecranon bursitis are rheumatoid arthritis and gouty arthritis, in that order (Fig. 84-6).2 In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the presentation can be variable. The bursa may rupture and dissect proximally, presenting as triceps swelling.32 In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the bursa may also communicate with the joint, dissect anteriorly and distally into the forearm, or even rupture and present as a subcutaneous fullness over the subcutaneous border of the ulna,11,14,34 all complications that are usually relatively painful.

The association of triceps tendon rupture with olecranon bursitis after trauma has been cited.7 I have seen a bursa-type reaction after subacute or partial distal biceps rupture and suspect that the bursal reaction was an effect of biceps tendon injury and partial rupture, rather than a cause of rupture. On the other hand, traumatic bursitis is surprisingly painless after the initial event. When the bursitis is symptomatic, flexing the elbow to more than 90 degrees causes most symptoms. In fact, positions between 60 and 90 degrees have been shown in the laboratory to produce considerably greater pressure in the bursa than elbow extension.4 Canoso noted no pain with flexion, even when the bursa was distended, and speculated that discomfort probably originated in nerve endings in the osseous tendinous attachment, rather than in the roof of the bursa. Loss of motion has been reported, but this must be uncommon. I have not yet observed this in my practice. This phenomenon was first described by Irby and colleagues in 1975.17

Another clinical setting in which olecranon bursitis is becoming an increasingly recognized complication is hemodialysis.8,17,19 As many as 7% of dialysis patients may be affected.17,19 The pathophysiology of this manifestation has not been demonstrated conclusively. It is possible that direct pressure or low-grade trauma from posturing of the elbow may be the principal insult. Use of anticoagulants increases the possibility of hemobursitis (Fig. 84-7). It has also been proposed that it may represent uremic serositis, but none of these possibilities has been confirmed.19 A septic cause has been reported in about 25 percent of cases.19

Canoso has also characterized the clinical features of 30 cases of noninflammatory olecranon bursitis.3 Repetitive trauma was reported in 14 cases and a discrete, single traumatic event in seven. The nine other cases might be considered idiopathic. An olecranon spur was observed in 10 of 30 patients (Fig. 84-8). When symptoms had been present more than 2 weeks, the bursa appeared discretely swollen; when symptoms had been present less than 2 weeks, parabursal edema was observed in the arm and forearm in half of the patients (Fig. 84-9).8

TREATMENT

ACUTE BURSITIS

Control of any underlying systemic or inflammatory process is the obvious first step in treatment. Sometimes the olecranon bursa communicates with the joint in rheumatoid arthritis, and the inflammation is generally considered a secondary process.16 If the bursa is not painful, local measures to prevent injury are all that is required.12 A resting splint and compression may be necessary, and this is the usual treatment in the early stages. Acute traumatic or idiopathic bursitis is also treated symptomatically with elbow pads (Fig. 84-10).

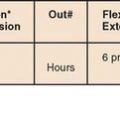

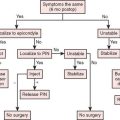

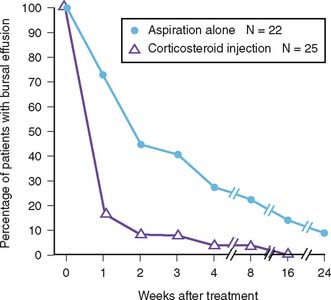

If pain in the bursa prevents daily or occupational activity, aspiration and cortisone injection are indicated. Weinstein and colleagues42 reviewed 47 patients with nonseptic bursitis who were followed for 6 months to 5 years. Aspiration with and without corticosteroids demonstrated that adding corticosteroids did reduce the chance of recurrence but was associated with a significantly greater complication rate. Infection developed in three of 25 patients, and subdermal atrophy in five of 25 (Fig. 84-11).

FIGURE 84-11 Temporal resolution of bursitis associated with treatment by aspiration with and without cortisone injection.

(Redrawn from Weinstein, P. S., Canoso, J. J., and Wohlgethan, J. R.: Long-term follow-up of corticosteroid injection for traumatic olecranon bursitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 43:45, 1984.)

The orthopedic surgeon must be particularly vigilant here. “Nonsurgeons” tend to treat the septic process for a long time before they consider intervention.44 If the process does not rapidly resolve, if pain persists, and if parabursal swelling or erythema is present and is not resolving, septic bursitis is likely and the bursa must be aspirated. If this has already been done and the initial aspirate revealed no bacteria, repeat aspiration is indicated; at this time, culture is occasionally “positive.”

CHRONIC BURSITIS

Chronic recurrent or painful olecranon bursitis may require more definitive measures. A 16-gauge indwelling needle that maintains drainage with a compressive dressing for about 3 days has been cited as being effective in reducing recurrence of bursal swelling.12 Knight and colleagues,21 who refined this technique using percutaneous placement of a suction irrigation system, reported the results of 10 cases of septic olecranon bursitis. The average time in the hospital was approximately 12 days.42 Today, because increasing pressure for patient dismissal compromises this form of treatment, it is uncommon. Surgery is not commonly indicated; however, when the process is refractory to nonoperative measures and is interfering with occupational or daily activities, operative intervention should be considered.

OPERATIVE INTERVENTION

Endoscopic Procedures

Not surprisingly, endoscopic management of chronic olecranon bursitis has now been described.36 Nine patients were successfully treated by this technique with more rapid return to work than a control group treated in the traditional manner. This technique may be of value; time will tell.

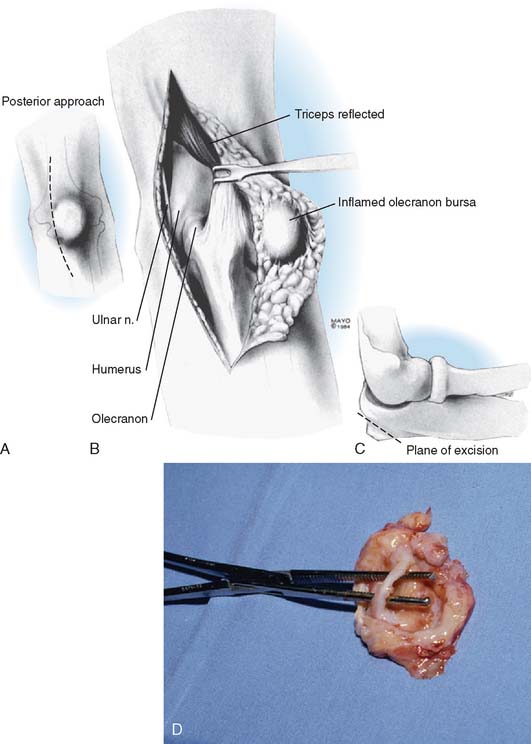

Open Procedure

A longitudinal incision medial to the midline39 or a transverse incision has been recommended.38 All bursal tissue is removed, and the joint is immobilized in flexion or extreme flexion for approximately 2 weeks. Freeing the bursa from the skin can devitalize the skin over the olecranon process or cause problems with healing. Thus, I recommend a compressive dressing on the elbow placed in about 45 degrees of flexion. To avoid this, a rather unusual approach has been reported by Quayle and Robinson35 (Fig. 84-12). The concern about wound healing attendant to the subdermal dissection of the bursa is avoided by reflecting the skin with the bursal tissue from the tip of the olecranon in a lateral to medial or a medial to lateral direction. At this point, the tip of the olecranon is obliquely osteotomized, leaving the bursal tissue intact. The triceps mechanism is then reflected back over the olecranon, and the wound is closed with a drain. Eleven patients treated with this technique have had no recurrences.35

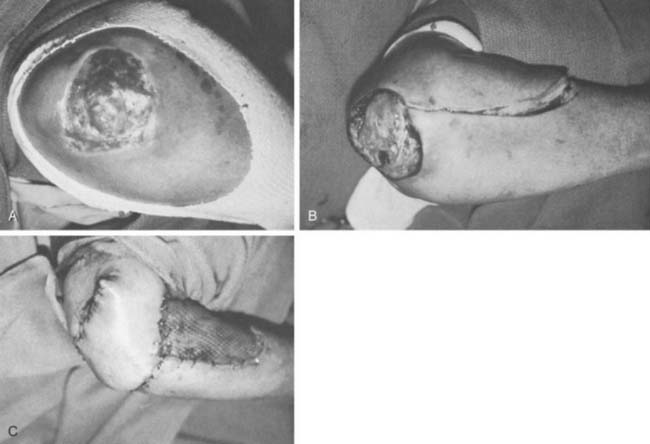

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

In the last several years, a fasciocutaneous flap technique has been described by Lamberty and Cormack23 to cover defects around the olecranon process of the ulna. The flap involves a single stage local transport of tissue from the forearm (Fig. 84-13). The viability of the transfer rests on the circulation of the fascia for viability. The donor site over the forearm is closed primarily as well as with a split-thickness skin graft as needed. Several authors have recently documented the effectiveness of this or a modification of this procedure.9,23,40 Alternatively, a more proximal flap may be elevated based on a single local perforator vessel and medialized distally.13

RESULTS

Stewart and associates39 reviewed the Mayo Clinic experience with 21 cases of surgical excision of the olecranon bursa. Not surprisingly, only two of five patients with rheumatoid arthritis (40%) enjoyed complete relief. Fortunately, 15 of 16 (94%) in the nonrheumatoid group were free of recurrence an average of 5 years after surgery.39

COMPLICATIONS

Complications of wound healing are the most common ones associated with incision and drainage or with excision of the olecranon bursa (Fig. 84-14). We had no recurrent drainage after the 21 resections reported by Stewart and associates. Should coverage be a problem, however, muscle flap transfers, either free or local, have been used with success for this application. Lai and colleagues recently described a more limited adipofascial flap to cover this area.22 Indiscriminate incision or removal of the olecranon bursa must be seriously questioned in light of the possibility and magnitude of this complication.

1 Bourne M., Morrey B.F. Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1991;271:143.

2 Bywaters E.G. The bursae of the body. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1965;24:215.

3 Canoso J.J. Idiopathic or traumatic olecranon bursitis. Clinical features and bursal fluid analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:1213.

4 Canoso J.J. Intrabursal pressures in the olecranon and prepatellar bursae. J. Rheumatol. 1980;7:570.

5 Carp L. Tennis elbow. Arch. Surg. 1932;24:905.

6 Chen J., Alk D., Eventov I., Weintroub S. Development of the olecranon bursa: An anatomic cadaver study. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1987;58:408.

7 Clayton M.C., Thirupathi R.G. Rupture of the triceps tendon with olecranon bursitis. Clin. Orthop. 1984;184:183.

8 Cruz C., Shah S.V. Dialysis elbow: Olecranon bursitis from long-term hemodialysis. J. A. M. A. 1977;238:238.

9 Davalbhakta A.V., Niranjan N.S. Fasciocutaneous flaps based on fascial feeding vessels for defects in the periolecranon area. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1999;52:60.

10 Davis W.M., Yassine Z. An etiologic factor in tear of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1956;38A:1365.

11 Ehrlich G.E. Antecubital cysts in rheumatoid arthritis: A corollary to popliteal (Baker’s) cysts. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A:165.

12 Fisher R.H. Conservative treatment of disturbed patellae and olecranon bursae. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1977;123:98.

13 Frost-Arner L., Bjorgell O. Local perforator flap for reconstruction of deep tissue defects in the elbow area. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2003;50:491.

14 Goode J.D. Synovial rupture of the elbow joint. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1968;27:604.

15 Ho G., Tice A.D. Comparison of nonseptic and septic bursitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1979;139:1269.

16 Hollinshead W.H. Anatomy for Surgeons, 2nd ed. Vol. 3. New York: Hoeber, 1969.

17 Irby R., Edwards W.M., Gatter R.J. Articular complications of hemotransplantation and chronic renal hemodialysis. Rheumatology. 1975;2:91.

18 Jaffe L., Fetto J.F. Olecranon bursitis. Contemp. Orthop. 1984;8:51.

19 Jain V.K., Cestero R.V.M., Baum J. Septic and aseptic olecranon bursitis in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin. Exp. Dial. Apheresis. 1981;5:405.

20 Karanjia N.D., Stiles P.J. Cubital bursitis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70B:832.

21 Knight J.M., Thomas J.C., Maurer R.C. Treatment of septic olecranon and prepatellar bursitis with percutaneous placement of a suction-irrigation system: A report of 12 cases. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1986;206:90.

22 Lai C.S., Tsai C.C., Liao K.B., Lin S.D. The reverse lateral arm adipofascial flap for elbow coverage. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1997;39:196.

23 Lamberty B.G., Cormack G.C. Fasciocutaneous flaps. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1990;17:713.

24 Larson R.L., Osternig L.R. Traumatic bursitis and artificial turf. J. Sports Med. 1974;2:183.

25 Lasher W.W., Mathewson L.M. Olecranon bursitis. J. A. M. A. 1928;90:1030.

26 Letizia G., Piccione F., Ridola C., Zummo G. Ultrastructural comparisons of human synovial membrane in joints exposed to varying stresses. Ital. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 1980;6:279.

27 MacFarlane J.D., van der Linden S.J. Leaking rheumatoid olecranon bursitis as a cause of forearm swelling. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1981;40:309.

28 Mathews R.E., Gould J.S., Kashlan M.B. Diffuse pigmented villonodular tenosynovitis of the ulnar bursa: A case report. J. Hand Surg. 1981;6:64.

29 McCarty D.J., Gatter R.A. Recurrent acute inflammation associated with focal apatite crystal deposition. Arthritis Rheum. 1966;9:84.

30 Monro A. A Description of All the Bursae Mucosae of the Human Body. Edinburgh: Elliot, 1788.

31 Osgood R.B. Radiohumeral bursitis, epicondylitis, epicondylalgia (tennis elbow). Arch. Surg. 1922;4:420.

32 Petrie J.P., Wigley R.D. Proximal dissection of the olecranon bursa in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 1984;4:139.

33 Pien F.D., Ching D., Kim E. Septic bursitis: Experience in a community practice. Orthopaedics. 1991;14:981.

34 Pirani M., Lange-Mechlen I., Cockshott W.P. Rupture of a posterior synovial cyst of the elbow. J. Rheumatol. 1982;9:94.

35 Quayle J.B., Robinson M.P. A useful procedure in the treatment of chronic olecranon bursitis. Injury. 1976;9:299.

36 Schulze J., Czaja S., Linder P.E. Comparative results after endoscopic synovectomy and open bursectomy in chronic bursitis olecrani. Swiss Surg. 2000;6:323.

37 Smith D.L. Septic and nonseptic olecranon bursitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1989;149:1581.

38 Smith F.M. Surgery of the Elbow, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1972.

39 Stewart N.J., Manzanares J.B., Morrey B.F. Surgical treatment of aseptic olecranon bursitis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:49-53.

40 Van Landuyt K., De Cordier B.C., Monstrey S.J., Bondeel P.N., Tonnard P., Verpaele A., Matton G. The antecubital fasciocutaneous island flap for elbow coverage. Ann Plast. Surg. 1998;41:252.

41 Vizkelety T., Aszodi K. Bilateral calcareous bursitis at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50B:644.

42 Weinstein P.S., Canoso J.J., Wohlgethan J.R. Long-term follow-up of corticosteroid injection for traumatic olecranon bursitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1984;43:44.

43 Whittaker C.R. The arrangement of the bursae in the superior extremities of the full-term fetus. J. Anat. Physiol. 1910;44:133.

44 Zimmerman B.3rd, Mikolich D.J., Ho G.Jr. Septic bursitis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;24:391-410.