11 Bursae Injections

Bursitis is commonly diagnosed and treated in clinical practices that focus on musculoskeletal medicine. Inflamed bursae often respond to conservative treatments including rest, cryotherapy, compression, physical/occupational therapy and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1a In patients who fail to respond to conservative rehabilitation, a corticosteroid injection into the bursa can serve as a useful diagnostic and therapeutic adjunct to a comprehensive course of rehabilitation.

Physical examination will reveal focal tenderness, swelling, and pain during direct palpation. If the injury is due to acute trauma, a fracture or ligamentous instability of the joint should be considered. In cases of chronic bursitis, calcifications may be identified on plain radiographs. However, the most common etiology combines repetitive motion with improper biomechanics. The physical examination should include a survey of peripheral joints to rule out a systemic process such as an underlying rheumatic disease. Skin overlying the area of tenderness should be examined for evidence of warmth, redness, swelling, or penetrating trauma. Rarely an infected bursa is diagnosed, and skin warmth appreciated on palpation may be the most sensitive physical indicator.1 The treatment of bursitis requires that an infection be considered prior to initiating treatment protocols. Aspiration of a septic bursa and identification of a bacterial pathogen are necessary to initiate appropriate antibiotic treatment. Laboratory studies of the serum should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood cell count, and microscopic examination to screen for leukocytosis, bacteria on Gram stain, or crystals. Operative incision and drainage of a septic bursa may be required for effective treatment.2,3 Contraindications to bursal injection with corticosteroids include cellulitis, generalized infection, and coagulation disorders.

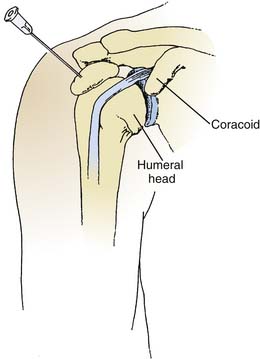

Subacromial (Subdeltoid) Bursitis

The subacromial bursa rests on the supraspinatus and is covered by the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, and the deltoid. This is the most common site of bursitis of the shoulder, with inflammation usually occurring secondary to rotator cuff tendinitis or shoulder impingement syndrome. In a pure subacromial bursitis, the impingement signs may be absent, and the inflamed bursa may limit full passive abduction due to compression at the near end range of shoulder motion.4 More commonly, subacromial bursitis coexists with impingement syndrome or rotator cuff syndrome. Determining the etiology of shoulder pain may be difficult, and a diagnostic injection into the bursa can narrow the field of possibilities. A diagnostic injection may help distinguish weakness and loss of range of motion secondary to a painful bursitis from a full-thickness rotator cuff tear. The patient should be thoroughly examined prior to the administration of local anesthetic and then reexamined 5 to 10 minutes after injection. Postinjection, the patient may be less guarded and more cooperative during the physical examination, yielding further diagnostic information.

Although an anterior, posterior, or lateral approach may be used, the posterolateral approach is preferred. Following sterile technique, the skin is cleansed with povidone-iodine, and the patient is directed to retract the shoulder to a neutral posture. The posterolateral angle of the acromion is identified by palpation, and the needle is advanced in an anteromedial and slightly inferior direction (Figs. 11-1 and 11-2).5 If the soft tissues resist needle insertion, a small volume can be injected to expand the bursa so that the needle can be advanced further, resulting in optimal needle position. A mixture of 2 to 4 mL of 1% or 2% lidocaine hydrochloride and 2 to 4 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine hydrochloride is injected into the bursa after a 25-gauge, 1.5-inch needle is introduced approximately 1 inch.6 In the authors’ experience, an inflamed subacromial bursa accepts 4 to 6 mL of total volume. Following the injection, a reduction of pain with improved strength supports the diagnoses of shoulder impingement, supraspinatus tendinitis, and subdeltoid bursitis. Patients who respond with greater than 50% relief are good candidates for an immediate follow-up injection with 1 mL of betamethasone sodium phosphate.6 Alternatively, the anesthetics can be mixed with the corticosteroids and administered in a single injection when the clinical examination is clear. Subacromial bursography is helpful when the initial blind anesthetic injection is unsuccessful or in a patient whose diagnosis is unclear. A normal bursogram casts doubt on a diagnosis of subacromial impingement.7

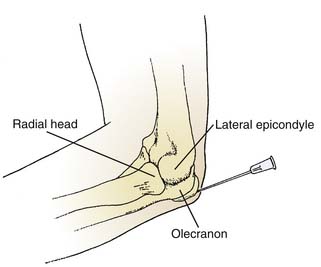

Olecranon Bursitis (Draftsmen’s Elbow)

The olecranon bursa is subcutaneous, protecting the proximal ulna frequently subjected to trauma. Inflammation of this bursa is commonly associated with rheumatologic disorders. Aspiration of the bursa should always precede injection and may be helpful to ensure proper location of the needle because the wall of the bursa is often thickened and fibrotic from chronic irritation. Gout may be seen at the olecranon, and any bursal fluid aspirated should undergo microscopic examination for crystals. Aspiration of the bursa is more successful using a larger bore needle (18 gauge), because the fluid may be gelatinous. The needle enters the skin perpendicular to the central swelling while the clinician withdraws on the syringe (Fig. 11-3).5 The procedure is followed with the application of a compressive dressing, and the patient is instructed to protect the elbow from further trauma. Persistent cases may benefit from a low-dose corticosteroid injection. Rarely, surgical excision or an arthroscopic bursectomy is warranted after failure of conservative measures.2

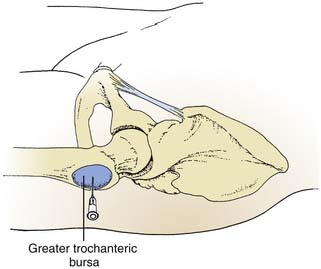

Trochanteric Bursitis

Trochanteric bursitis is commonly seen in an elderly population and manifests as pain in the lateral thigh during ambulation.5a Patients may describe a pseudoradicular pattern with the pain extending down the lateral aspect of the lower extremity and into the buttock. The symptoms can be elicited by placing the lower extremity in external rotation and abduction. Direct palpation or deep pressure applied posterior and superior to the trochanter will reproduce the pain.8 The patient should be examined for limitations in flexibility involving the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus and the tensor fasciae latae. Trendelenburg gait as a result of hip abduction weakness may contribute to increased friction and irritation of the bursa. If the history and physical examination are consistent with bursitis, a corticosteroid combined with anesthetic agent is delivered via a 3.5-inch, 22-gauge needle directed at the point of maximal tenderness overlying the greater trochanter (Fig. 11-4).5,9 Persistent hip pain despite injection therapy and comprehensive rehabilitation should alert the physician to alternate sources of pain including the lumbar spine, hip joint, and distal lower extremity joints.10,11

Iliopectineal Bursa

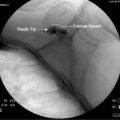

The iliopectineal (iliopsoas) bursa, the largest bursa near the hip joint, is located anterior to the hip capsule and is covered by the iliopsoas. Inflammation of the bursa is not particularly common and may be functionally limiting in that it causes the patient to avoid extension of the lower extremity during the gait cycle. Patients hold the lower extremity in external rotation with the hip in flexion to relieve pressure on the inflamed bursa. Referral pain following the femoral nerve distribution may be seen in cases of iliopectineal bursitis. The examiner may elicit symptoms by passively extending the hip in either a supine or prone position. Injection under fluoroscopic guidance is recommended because the bursa may communicate with the hip capsule and correct needle placement is essential.8,12 Once placement is confirmed by a bursogram, a mixture of anesthetic and corticosteroid is injected through the 3.5-inch spinal needle.

Ischial Bursitis

The ischial bursa lies between the ischial tuberosity and the gluteus maximus. The examiner’s index of suspicion must be high because ischial bursitis—so-called “tailor’s or weaver’s bottom”—is not common. Classically, ischial bursitis occurs from friction and the trauma of prolonged sitting on a hard surface. It may occur in adolescent runners, often in conjunction with ischial apophysitis. Pain is most commonly aggravated during uphill running.13 The pain is distributed down the posterior aspect of the thigh and occurs with activation of the hamstring muscles. Initial treatment approaches should address modification of the patient’s activity, including a decrease in the duration and frequency of running. If an alternative to running includes cycling, the patient should be advised to avoid the use of toe clips, which increase activation of the hamstrings. When the etiology is due to prolonged sitting, the patient’s work station should be modified to allow activities to be conducted in a standing position, and a cushion should be used during sitting. Ice and NSAIDs are helpful in controlling symptoms. Adolescent athletes may require a radiologic series to screen for callus formation secondary to ischial apophysitis if the pain does not resolve with conservative measures. Persistent pain may benefit from injection as an adjunct to rest, ice, and NSAIDs. To perform this, the patient lies on his or her side with the knees fully flexed to relax the hamstrings. A 3-inch, 22-gauge needle is held in a horizontal position and directed toward the point of maximal tenderness overlying the ischial tuberosity. The injection of contrast dye into the bursa under fluoroscopy may be necessary to verify needle placement.

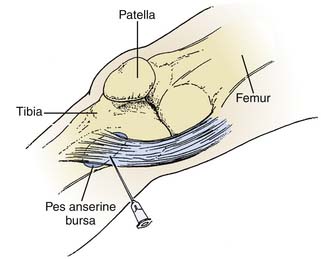

Anserine Bursitis

The anserine bursa separates the three conjoined tendons of the pes anserinus, or goose’s foot (semitendinosus, sartorius, and gracilis muscles), from the medial collateral ligament and the tibia. It is one of the most commonly inflamed bursae in the lower extremity. Anserine bursitis is commonly seen in women with heavy thighs and osteoarthritis of the knees. The bursa may also become inflamed as the result of direct trauma in athletes, especially soccer players.4,13 Patients report pain inferior to the anteromedial surface of the knee with ascension of stairs. Moving the patient’s knee in flexion and extension while internally rotating the leg will reproduce the symptoms. The palpatory examination will localize the pain to the anserine bursa. The injection is straightforward and effective in reducing inflammatory symptoms. After sterile preparation, the knee is fully extended and a 1.0- to 1.5-inch, 22-gauge needle is directed at the point of maximal tenderness (Fig. 11-5)5 to deliver a 1- to 3-mL combination of anesthetic and corticosteroid. The patient should enter a rehabilitation program emphasizing flexibility, and the athlete at risk for repetitive trauma may benefit from padded knee protection.

Tibial Collateral Ligament Bursitis

The tibial collateral ligament (TCL) bursa, referred to as the “no name, no fame” bursa,14 is located between the deep and superficial aspects of the tibial collateral ligament.14a The bursa does not adhere to the medial meniscus, and it appears to reduce friction between the superficial layer of the TCL and the medial meniscus. TCL bursitis should be considered in any patient with medial joint line tenderness. During a 3-year study, Kerlan found that 5% of orthopedic patients presenting with medial knee pain suffered from TCL bursitis.15 Physical examination will not show evidence of new ligamentous or capsular instability. Treatment consists of a local injection of lidocaine (2 to 4 mL) and 1 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg/mL)15 directed perpendicular to the medial joint line at the point of maximal tenderness (Fig. 11-6).

Calcaneal Bursitis

Calcaneal bursitis often develops in elderly patients from a calcified spur that subjects the bursa to trauma after prolonged walking or running. Evaluation of the footwear may reveal poor shock-absorbing capacity. Injection into the point of maximum tenderness may have diagnostic and therapeutic value. Selection of an appropriate walking or running shoe and the use of a heel cup are beneficial. Athletes should be encouraged to change running shoes every 200 to 300 miles because midsole breakdown occurs after this amount of wear.16

Pharmacologic Agents for Bursal Injection

A number of local anesthetics are available for bursal injections, and clinicians should be familiar with their pharmacologic properties. Concentrations of 0.5% to 1.0% lidocaine or 0.25% to 0.5% bupivacaine are appropriate for bursal injection. The onset and duration of the anesthetic effect is related to the volume and concentration injected. Lidocaine has an onset of action within 5 to 15 minutes and may last 3 to 4 hours, whereas bupivacaine begins to work in 10 to 20 minutes, but the anesthetic effect can last 4 to 6 hours.17 Bach describes the benefits of using a combination of lidocaine hydrochloride and bupivacaine hydrochloride in subacromial space injections to obtain an early onset of action with prolonged anesthesia.6

Corticosteroids are widely available and very effective in alleviating bursal inflammation. Corticosteroids of intermediate or long duration are suitable for treatment of bursitis. Triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL) is a commonly used intermediate-acting agent with a half-life of 24 to 36 hours. Betamethasone is a longer acting corticosteroid with a half-life of 36 to 72 hours and a relative antiinflammatory potency five times greater than triamcinolone.17 The dosage is adjusted to the size of the bursa, and the lowest effective dose should be delivered to the bursa. Clinicians may want to avoid corticosteroid injection acutely (the first 7 days after an initial injury) because corticosteroids theoretically inhibit the healing process.18 About 14 to 21 days after injury, glucocorticoids can control the inflammation and edema of the proliferative phase. The Achilles, patellar, and rotator cuff tendons should be avoided because direct injection into the tendon can place the patient at risk for rupture.18

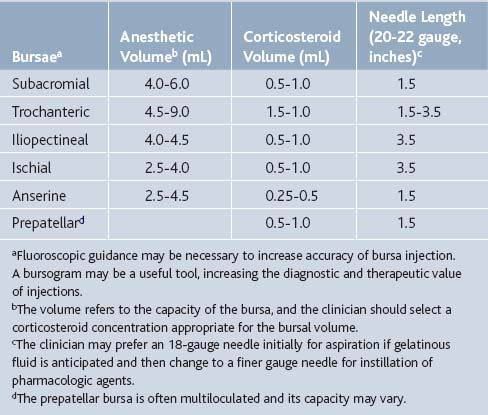

The clinician must be careful to select a combination of medications within the recommended volumes to avoid further injury to the bursae. Table 11-1 may be used as a guideline for selecting the type and volume of corticosteroid and anesthetic to be administered.

1. Smith D.L., McAfee J.H., Lucas L.M., et al. Septic and non-septic olecranon bursitis: Utility of the surface temperature probe in the early differentiation of septic and nonseptic cases. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1581-1585.

1a. Kelley W.N., Harris E.D., Ruddy S., Sledge C.B. Textbook of Rheumatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. 545-560

2. Kerr D.R. Prepatellar and olecranon arthroscopic bursectomy. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:137-142.

3. Waters P., Kasser J. Infection of the infrapatellar bursa. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72A:1095-1096.

4. Magee D.J. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008. p 706

5. Vander Slam T.J. Atlas of Bedside Procedures. Boston: Little Brown; 1988. 455, 459, 461

5a. Swezey R.L. Pseudo-radiculopathy in subacute trochanteric bursitis of the subgluteus maximus bursa. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1976;57:387-390.

6. Bach B.R., Bush-Joseph C. Subacromial space injections: A tool for evaluating shoulder pain. Physician Sportsmed. 1992;2:93-98.

7. Nicholas J.A., Hershman E.B. The Upper Extremity in Sports Medicine. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. 124-125

8. Klippel J.H., editor. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation. 2008:143-146.

9. Ege Rasmussen K.J., Fanø N. Trochanteric bursitis: Treatment by corticosteroid injection. Scand J Rheumatol. 1985;14:417-420.

10. Collée G., Dijkmans B.A., Vandenbroucke J.P., Cats A. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (trochanteric bursitis) in low back pain. Scand J Rheumatol. 1991;20:262-266.

11. Traycoff R.B. “Pseudotrochanteric Bursitis”: The differential diagnosis of lateral hip pain. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1810-1812.

12. Shbeeb M.I., Matteson E.L. Trochanteric bursitis (greater trochanter pain syndrome). Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:565-569.

13. Reid D.C. Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. 631, 1564, 1625–1626, 1636

13a. Hemler D.E., Ward W.K., Karstetter K.W., Bryant P.M. Saphenous nerve entrapment caused by pes anserine bursitis mimicking stress fracture of the tibia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:336-337.

14. Stuttle F.L. The no-name, no-fame bursa. Clin Orthop. 1959;15:197-199.

14a. Lee J.K., Yao L. Tibial collateral ligament bursa: MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;178:855-857.

15. Kerlan R.K., Glousman R.E. Tibial collateral ligament bursitis. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:344-346.

16. Young J.L., Press J.M. Rehabilitation of running injuries. In: Buschbacher R.H., Braddom R.L., editors. Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation: A Sport-Specific Approach. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 1994:123-134.

17. Covino B.G., Scott D.B. Handbook of Epidural Anesthesia and Analgesia. Orlando: Grune & Stratton; 1985. 58-74

18. Saal J.A. General principles and guidelines for rehabilitation of the injured athlete. Phys Med Rehabil State Art Rev. 1987;1:523-536.