Chapter 18 Breast

COMMON CLINICAL PROBLEMS FROM BREAST DISEASE

| Sign or symptom | Pathological basis |

|---|---|

| Lump | |

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

Development

Structure

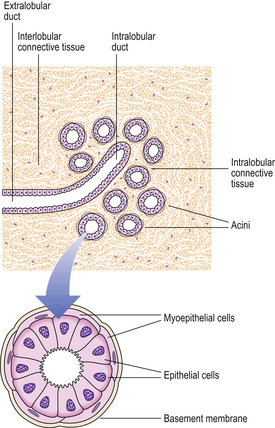

The main function of the breast is the production and expression of milk (Fig. 18.2).

Lobules

The lobules are the secretory units of the breast. Each lobule consists of a variable number of acini, or glands, embedded within loose connective tissue and connecting to the intralobular duct (Fig. 18.3). Each acinus is composed of two types of cell, epithelial and myoepithelial. The epithelial cells are secretory. Although synthesising milk only during the later stages of pregnancy and post-partum, they continuously secrete a variety of glycoproteins into the glandular lumens. They are surrounded by myoepithelial cells which contact with the basement membrane and may directly or indirectly control luminal cell function. The intralobular duct connects with the extralobular duct and this, together with the lobule, is called the terminal ductal lobular unit.

Ducts

The extralobular ducts within the same area link together to form subsegmental ducts, which link in turn to form segmental ducts. These drain into the lactiferous ducts and sinuses (Fig. 18.2) which empty on to the surface of the nipple through separate orifices. There are 15 to 20 lactiferous ducts, each draining a segment of breast. The ducts are lined by epithelial cells surrounded by myoepithelial cells. The connective tissue in which they lie is denser than that of the lobules, and they are surrounded by elastic tissue which helps in the drainage function of the ducts.

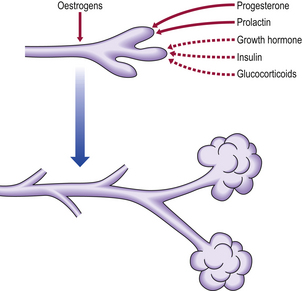

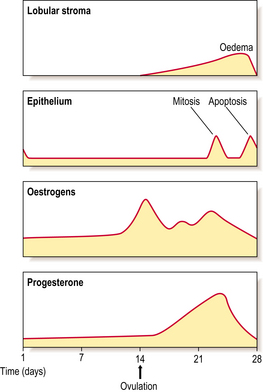

Cyclical variations

The breast undergoes minor changes during each menstrual cycle but these will vary if there is a failure of ovulation or if pregnancy intervenes. The breast is sensitive to changes in the levels of sex steroids during the different phases (Fig. 18.4). The lobular stroma becomes oedematous during the secretory phase, due to the effects of oestrogens, and this accounts for the breast fullness often felt in the premenstrual phase. An increase in the number of cells in mitosis occurs at days 22–24 of the cycle, coincident with the high peaks of oestrogen and progesterone; however, the numbers are never very high. A loss of cells occurs by apoptosis (Ch. 5) at the end of the cycle, due to a fall in hormone levels, so that an overall balance is maintained. In view of the changes that can occur in the breast in the second half of the menstrual cycle, it is better to examine clinically the breasts of a pre-menopausal woman in the first half of the cycle.

Pregnancy and lactation

During pregnancy, the lobules undergo controlled proliferation and enlargement in preparation for the synthetic and secretory activity of lactation. By the third trimester the number of acini in each lobule and the overall size of the lobules have markedly increased. The epithelial cells have become differentiated and they synthesise and secrete milk (Fig. 18.5). The various components of milk (casein, alpha-lactalbumin and milk fat globule membranes derived from the luminal surface of breast cells) are useful markers of the state of differentiation of breast cells, and because of this they have been extensively studied in breast disease.

Oestrogens, progesterone and prolactin, together with other hormones shown in Figure 18.1, are important in the development of the breast during pregnancy; however, once delivery occurs, the levels of sex steroids fall and it is prolactin that is necessary for the initiation of lactation. When breast feeding ceases there is a rapid involution of the differentiated lobular structure, and the breast returns to the pre-pregnancy structure.

Involution

Changes occur in the breast with increasing age; these involutional changes relate to the altered sex steroid levels that accompany decreasing ovarian function. The connective tissue of the lobules changes from a loose to a dense structure, the basement membranes around acini become thicker, and the lining cells of the acini are lost. These changes start in the pre-menopausal period and continue past the menopause; they often occur at an uneven rate, producing clinically palpable lumps. In elderly women, the major component of the breast is adipose tissue.

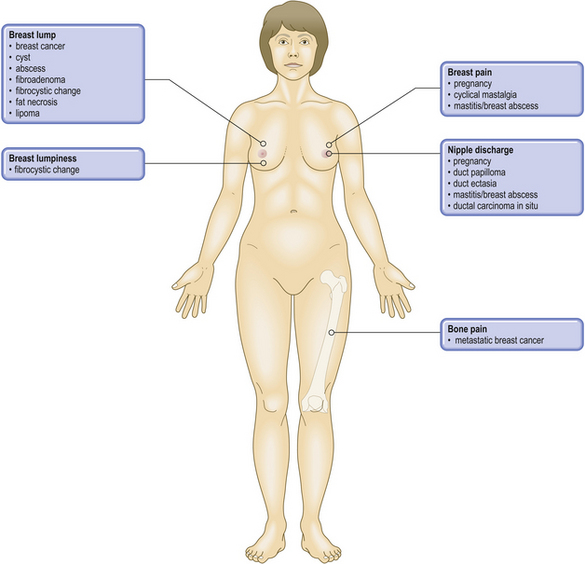

CLINICAL FEATURES OF BREAST LESIONS

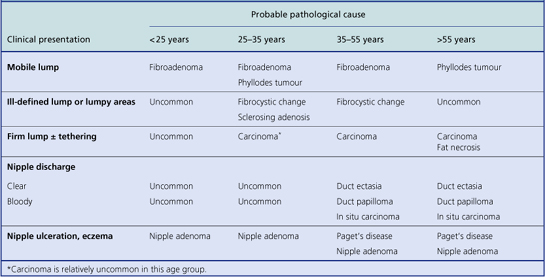

Most pathological lesions of the breast present as a lump or lumps. These can vary in their nature depending on their cause: well-circumscribed or ill-defined; single or multiple small nodules; soft or firm; mobile or attached to skin or underlying muscle. These features assist in the clinical distinction between benign breast lesions and breast carcinomas, but they are relatively weak discriminators on their own. Below the age of about 35, benign breast lumps are much more common than carcinomas. Most women with breast cancer are peri- or post-menopausal. The most likely type of lesion will vary with the age of the patient, although overlaps occur (Table 18.1). However, there can be exceptions and histological examination is mandatory for a definite diagnosis.

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

Fine-needle aspiration cytology

This technique is used in the clinic. A needle is inserted into the lump or area in the breast with the abnormality (guided if necessary by ultrasonography or mammography). Cells are aspirated, and after staining are examined by a pathologist; if the sample is adequate a diagnosis can be made. Women with benign conditions can be reassured and surgery may not be necessary. It is possible to prepare slides and a report while the patient is in the clinic.

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Mammary duct ectasia

The aetiology is unknown but the affected women are usually parous. The ducts are dilated and filled with white–green viscid matter; this material may be discharged from the nipple. The matter can usually be seen with the naked eye in excised tissue. The tissue around the ducts contains lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages, with a significant degree of fibrosis. Due to the inflammatory reaction, the condition is sometimes known as periductal mastitis.

Fat necrosis

Histologically, the appearances are the same as those of any adipose tissue that undergoes necrosis (Ch. 6): collections of macrophages and giant cells containing lipid material may be seen, and there is an associated reaction with lymphocytes, fibroblasts and small vascular channels. The necrotic fat acts as a persistent irritant, resulting in a chronic inflammatory process and hence fibrous tissue formation.

PROLIFERATIVE CONDITIONS OF THE BREAST

Fibrocystic change

Clinical and gross features

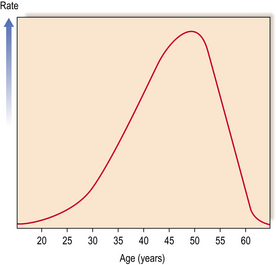

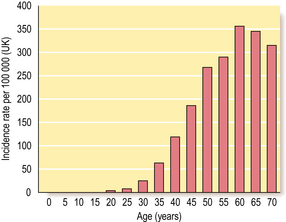

Proliferative lesions and their associated tissue responses generally occur between the ages of 30 and 55, with a marked decrease in incidence after the menopause. The incidence reaches a maximum in the years just before the menopause (Fig. 18.6).

Fig. 18.6 Incidence rates of benign proliferative breast changes occurring in women at different ages.

Surgery for benign conditions is now uncommon. If undertaken it is more common to find nodules of soft pink or grey tissue, up to 3 mm in diameter in younger women, whereas in women nearer the menopause cysts are frequently seen. These cysts can vary in size from 2 to 20 mm (Fig. 18.7) and, rarely, a solitary large cyst can be seen. The small cysts are often multiple. They frequently have a dark blue surface and, on opening, contain clear, yellowish or blood-stained fluid. The intervening tissue is usually firm due to the increase in fibrous tissue but the softer foci of epithelial proliferation can be seen and felt.

Histological features

A variety of histological changes can occur (Fig. 18.8). These are:

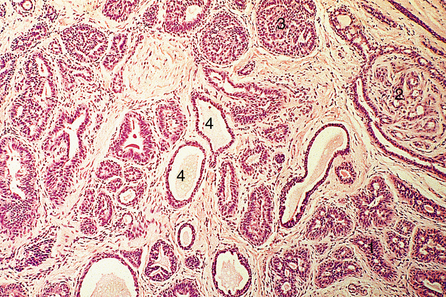

Sclerosing adenosis

In sclerosing adenosis there is lobular proliferation but the acini become distorted. The proliferation involves both epithelium and myoepithelium, but the latter tends to predominate. Large amounts of collagen can intervene between the glandular components, although the extent of this varies both within the same breast and between patients (Fig. 18.9). Due to the collagen component these lesions can mimic carcinomas clinically, and on mammograms where the associated calcification can be seen.

Epithelial hyperplasia

Epithelial hyperplasia, previously called epitheliosis, is the proliferation of epithelial cells that occurs in the small interlobular ducts, the intralobular ducts and the acini, resulting in a solid or almost solid mass obliterating the lumens (Fig. 18.10).

Apocrine metaplasia

Frequently the cysts, both large and small, are lined entirely or partly by cells that resemble the epithelium of the apocrine sweat glands. This condition is called apocrine metaplasia. The lining cells are large columnar cells with pink-staining (eosinophilic) cytoplasm, hence the alternative name ‘pink cell metaplasia’. It has no special clinical or prognostic significance.

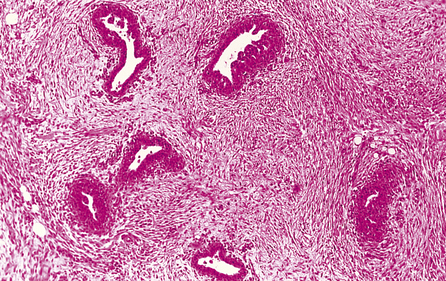

Lesions in men: gynaecomastia

Gynaecomastia is benign enlargement of the male breast tissue. The breast may resemble that of a young adolescent female in appearance and consistency, or there may be a firm, mobile disc beneath the nipple. The condition is unilateral in 75% of cases. The ducts are dilated and there is a variable degree of epithelial proliferation. The stroma around the ducts is often oedematous and myxoid, but in longstanding cases the stroma becomes dense and hyalinised (Fig. 18.11).

BENIGN TUMOURS

The benign breast tumours comprise:

Fibroadenoma

Gross appearance

Fibroadenomas are well circumscribed with a lobulated appearance (Fig. 18.12), and range in size from 10 to 40 mm in diameter, although larger tumours can occur in juvenile fibroadenoma (see below). The surrounding breast tissue can become compressed, but the tumour is not tethered; this lack of fixation accounts for its mobility on clinical examination, and the nickname of ‘breast mouse’. In young women, the tumours are soft and have a slightly gelatinous cut surface due to the loose connective tissue component; however, in older women they tend to be firmer as the connective tissue becomes more fibrous and sometimes calcified.

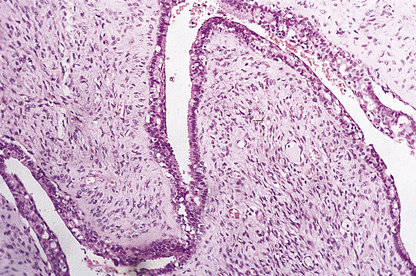

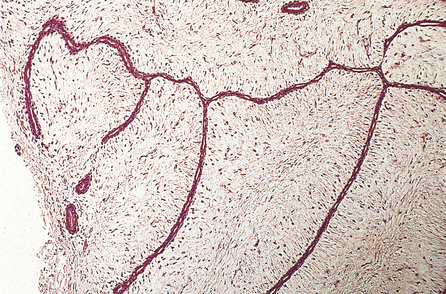

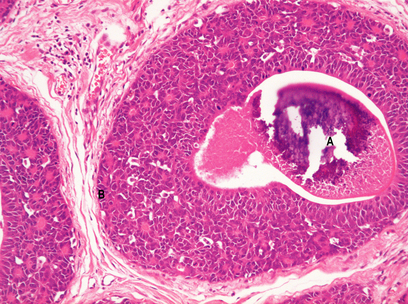

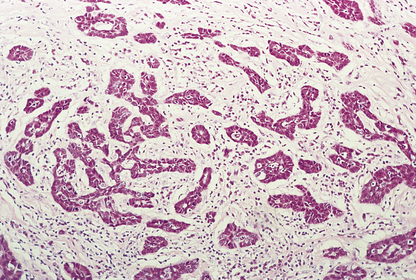

Duct papilloma

Duct papillomas arise as a solitary lesion within a large duct, up to 40 mm from the nipple. They appear either as an elongated structure extending along a duct, or as a spheroid which causes distension of the duct, making it cyst-like. The tumours have soft, pink or white outgrowths except when haemorrhage has occurred, in which case the surface will be brown from altered blood. Duct papillomas consist of branching fibrovascular cores covered by epithelium, which is cytologically benign (Fig. 18.14). Solitary duct papillomas are not premalignant; there is no increased risk of carcinoma.

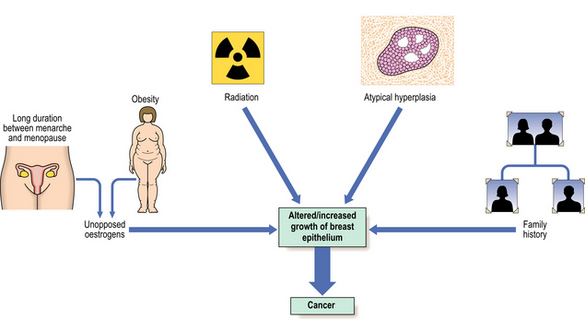

BREAST CARCINOMA

Many risk factors have been identified, and these, together with advances in the analysis of genetic and hormonal factors, have resulted in several aetiological hypotheses (Fig. 18.15). An understanding of these can help in the development of programmes directed towards the prevention of breast cancer. Schemes aimed at the early detection of breast cancer have been introduced in several countries.

Risk factors

The risk factors identified to date are:

Female sex and age

Around 1% of all breast cancers occur in men, so being female is an important risk factor. As with all carcinomas, increasing age is another significant factor. Up to the age of 50 years, the rate of increase is steep; it then slows down, although the incidence of breast cancer continues to increase into old age (Fig. 18.16).

Family history and genetic factors

Breast cancer is common, thus a history of a relative having breast cancer can be found in at least 10% of new cases. However, a proportion of these will be sporadic cancers and not due to familial (inherited genetic) factors. The risk of developing breast cancer is increased in first-degree relatives (e.g. sister, daughter) of breast cancer cases, particularly if that person is pre-menopausal. For example, the risk increases to nine-fold for first-degree relatives of pre-menopausal women with bilateral breast cancer. Up to five-fold increases in risk have been found for women with multiple first-degree relatives with breast cancer.

Aetiological mechanisms

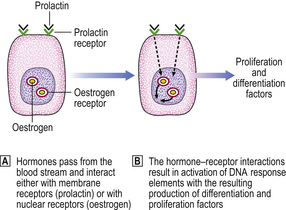

Hormone receptors

Hormones have an effect on cells only after interacting with specific receptors present on or in their target cells. The sex steroid, oestrogen, interacts with a nuclear receptor. Subsequent interaction with DNA results in the formation of differentiation- and proliferation-associated factors. Prolactin and other polypeptides interact with receptors on the cell surface (Fig. 18.17).

Oestrogen receptors can be detected in varying amounts in about 75% of breast cancers. The progesterone receptor, which can normally be formed only when the oestrogen receptor is present and active, is present in about 50% of tumours, and women whose tumours contain both types of receptor are more likely to respond to some form of hormone manipulation therapy. This suggests that hormones are important in the growth and maintenance of these carcinomas.

Non-invasive carcinomas

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Histologically, the changes are to be found in the small and medium-sized ducts, although, in older women, the larger ducts can be involved. The ducts contain cells that show cytoplasmic and nuclear pleomorphism to varying degrees. Mitotic figures may be frequent and can be abnormal. These features are used to classify ductal carcinoma in situ into high grade (more aggressive features) and non-high grade lesions. The ducts may be completely filled with cells (solid pattern), or have central necrosis (comedo pattern; Fig. 18.18) which may calcify, rendering the lesion mammographically detectable. The cribriform pattern of ductal carcinoma in situ has numerous gland-like structures within the sheets of cells. Ductal carcinoma in situ can spread along the duct system or into the lobules.

The previous management of ductal carcinoma in situ was generally mastectomy, so it is difficult to know the fate of these lesions if left. Estimates of residual carcinoma changing from non-invasive to invasive range from one-third to one-half, based on studies where there was local incomplete excision. If the tumour is completely removed the woman’s prognosis is excellent.

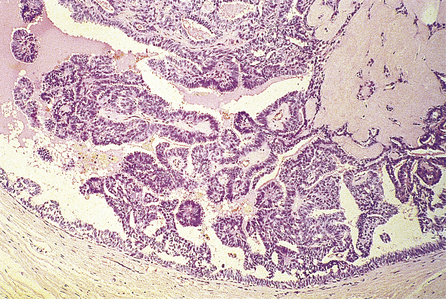

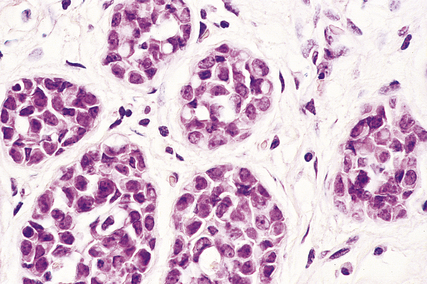

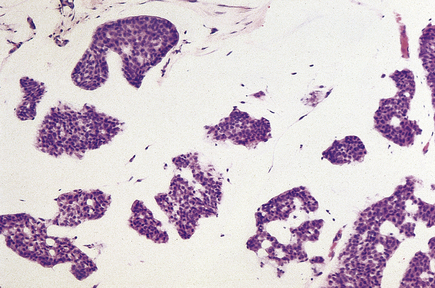

Lobular carcinoma in situ

Histologically, the changes are found in the acini—hence the term ‘lobular’—although they may extend into extralobular ducts and replace ductal epithelium (Fig. 18.19). Within the acini, the normal cells are replaced by relatively uniform cells with clear cytoplasm that appear loose and non-cohesive. The overall size of the acini increases, but the lobular shape is retained. Unlike the situation in ductal carcinoma in situ, necrosis is unusual.

Invasive carcinomas

The histological types of invasive carcinoma and their relative incidence for palpable tumours are:

There is a higher frequency of tubular carcinoma in mammographically detected tumours.

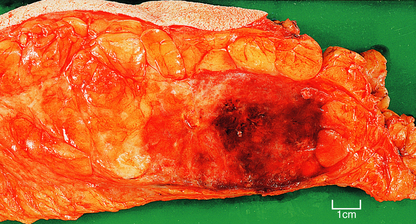

Carcinomas vary in size from less than 10 mm in diameter to over 80 mm, depending on whether detected by mammography or presenting clinically, but with the latter are often 20–30 mm in diameter. Clinically, they are firm on palpation and may show evidence of tethering to the overlying skin (Fig. 18.20) or underlying muscle. The skin may also show ‘peau d’orange’—dimpling due to lymphatic permeation. The nipple may be retracted due to tethering and contraction of the intramammary ligaments.

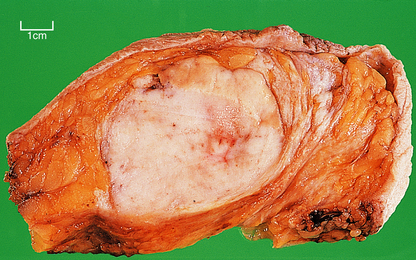

Gross features

The term scirrhous implies that there is a prominent fibrous tissue reaction, usually in the central part of the tumour. This results in the carcinoma having a dense white appearance, which grates when cut. Yellow streaks may be seen; these are due to the presence of elastic tissue within the tumour. Carcinomas with a prominent stromal reaction usually have irregular edges, extending into the adjacent fat or other structures (Fig. 18.20).

Medullary (brain-like) tumours are very cellular with little stroma. The edges of the carcinoma are often more rounded and discrete than those of the scirrhous tumours (Fig. 18.21). Necrosis is common. When palpated the tumours feel much softer.

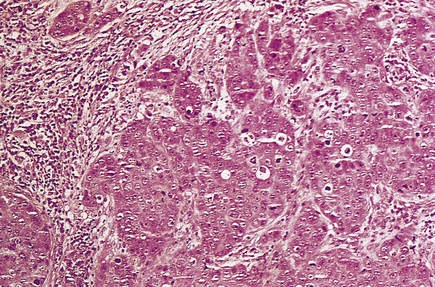

Infiltrating ductal carcinomas

Histologically, the tumour cells are arranged in groups, cords and gland-like structures. Quite marked variations can be seen between different carcinomas even though they are of the same type (Fig. 18.22). For example, the size of the solid groups of cells can be variable, and ductal carcinoma in situ is often present. The amount of stroma between the tumour cells can also vary, but in those carcinomas in which it is prominent it is most marked at the centre, with the periphery being more cellular. Collections of elastic tissue (elastosis) around ducts or within the stroma are common in tumours with a scirrhous reaction.

The degree of differentiation or grade of the tumour is based on the extent to which it resembles non-tumorous breast: whether the cells are in a gland-like pattern or as solid sheets; the degree of nuclear pleomorphism; and the number of mitotic figures present. A well-differentiated (grade I) infiltrating duct carcinoma tends to behave less aggressively than a poorly differentiated (grade III) tumour, which is composed of sheets of pleomorphic cells with large numbers of mitotic figures.

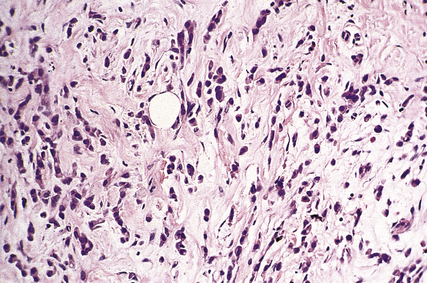

Infiltrating lobular carcinomas

Histologically the cells are small and uniform and are dispersed singly, or in columns one cell wide (‘Indian files’; Fig. 18.23), in a dense stroma. Elastosis can be present. The cells infiltrate around pre-existing breast ducts and acini, rather than destroying them as occurs with invasive duct carcinomas. This method of infiltration may account for the occasional multifocal nature of the tumours. The cells in some carcinomas may appear signet-ring in shape due to the accumulation of mucin within an intracytoplasmic acinus, displacing the nucleus to one side. A characteristic feature of these tumours is that the cells lack the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, which may account for their pattern of spread. Residual lobular carcinoma in situ can sometimes be found in the invasive tumours.

Mucinous carcinomas

Mucinous carcinomas (also known as colloid, mucoid and gelatinous carcinomas) usually arise in post-menopausal women and comprise 2–3% of invasive carcinomas.

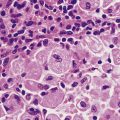

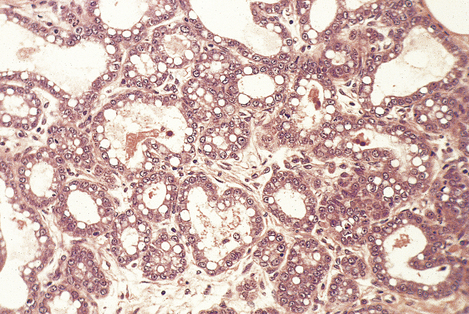

These carcinomas comprise small nests and cords of tumour cells, which show little pleomorphism, embedded in large amounts of mucin (Fig. 18.24). The latter is composed of neutral or weakly acidic glycoproteins, which are secreted by the tumour cells and are different from the proteoglycans of the stroma.

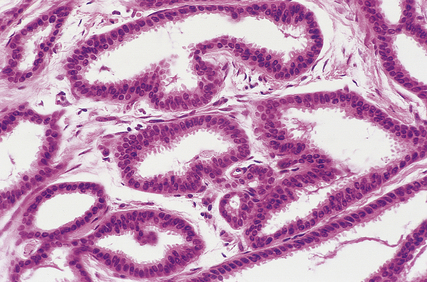

Tubular carcinomas

Histologically, they are composed of well-formed tubular structures, the cells of which show little pleomorphism or mitotic activity. The stroma is dense, often with elastosis (Fig. 18.25).

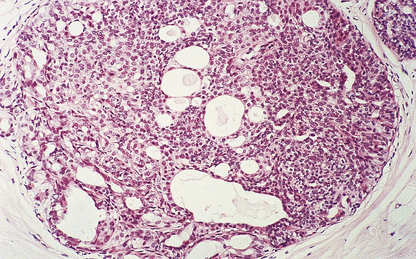

Medullary carcinomas

Medullary carcinomas are circumscribed and often large. Histologically, they are composed of large tracts of confluent cells with little stroma in between them. The cells show quite marked nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic figures are frequent. There is never evidence of gland formation. These cytological appearances put them into the ‘poorly differentiated’ category. Around the islands of tumour cells there is a prominent lymphocytic infiltrate, predominantly T-lymphocytes, with macrophages (Fig. 18.26).

Other types

Much rarer types of breast carcinoma include: adenoid cystic carcinomas; secretory carcinomas, which occur predominantly in juveniles; apocrine carcinomas, which are composed of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm; and carcinomas showing metaplasia, e.g. squamous, spindle cell, cartilaginous and osseous features.

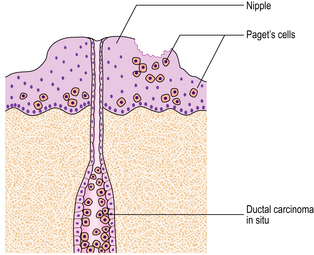

Paget’s disease of the nipple

Within the epidermis of the nipple, large, pale-staining malignant cells can be seen histologically and these cause the changes seen clinically. The malignant cells are derived from the adjacent breast carcinomas. A direct connection may not be seen. The relationship between Paget’s disease of the nipple and an underlying carcinoma is shown in Figure 18.27.

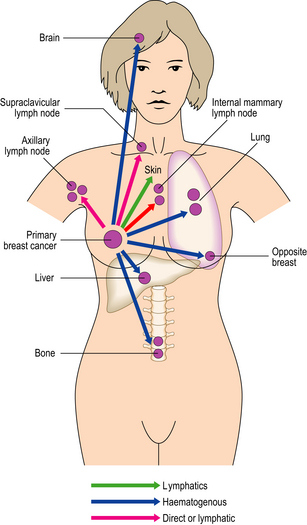

Spread of breast carcinomas

Breast carcinomas can infiltrate locally (direct spread) or metastasise to more distant sites via lymphatics and the blood stream and to pleura (Fig. 18.28).

Fig. 18.28 The common sites of metastasis from breast carcinoma via the lymphatic system or blood stream.

Breast carcinomas exhibit quite marked variation in the length of time between presentation of the primary carcinoma and the appearance of recurrent/metastatic disease. Some breast carcinomas never recur; in some patients reappearance of the disease may not be until as much as 20 years after the original excision, while for others it can be within 2–5 years. Tumour can recur at the site of the original excision and/or as distant metastases. The mechanisms by which a metastasis becomes clinically apparent after a long time interval are not known. They may relate to changes in tumour cells that have been lying dormant at that site, causing them to alter their behaviour, and/or to changes in the host response to the tumour.

Prognostic factors

Stage

When a woman presents with a breast carcinoma, staging is undertaken so as to assess the absence or presence and extent of spread both locally and distantly. The management of the patient will depend on the stage of the disease. The two main systems used are the International Classification of Staging and the TNM (Tumour, Node, Metastasis) system (Table 18.2).

Table 18.2 The main staging systems used to assess the extent of spread of breast carcinomas

| Stage | Extent of spread |

|---|---|

| International classification | |

| I | Lump with slight tethering to skin, but node negative |

| II | Lump with lymph node metastasis or skin tethering |

| III | Tumour that is extensively adherent to skin and/or underlying muscles, or ulcerating or lymph nodes are fixed |

| IV | Distant metastases |

| TNM | |

| T1 | Tumour 20 mm or less; no fixation or nipple retraction. Includes Paget’s disease |

| T2 | Tumour 20–50 mm, or less than 20 mm but with tethering |

| T3 | Tumour greater than 50 mm but less than 100 mm; or less than 50 mm but with infiltration, ulceration or fixation |

| T4 | Any tumour with ulceration or infiltration wide of it, or chest wall fixation, or greater than 100 mm in diameter |

| N0 | Node-negative |

| N1 | Axillary nodes mobile |

| N2 | Axillary nodes fixed |

| N3 | Supraclavicular nodes or oedema of arm |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

HER-2

The oncogene c-erbB-2/HER-2 is altered in approximately 20% of invasive breast carcinomas. There is amplification of the gene with resultant overexpression of the membrane-related protein. Patients whose carcinomas have this alteration have a poorer prognosis. A humanised monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab (Herceptin) has been developed, which can be used as adjuvant treatment and to treat women with metastatic disease, if the cancers have the molecular alteration.

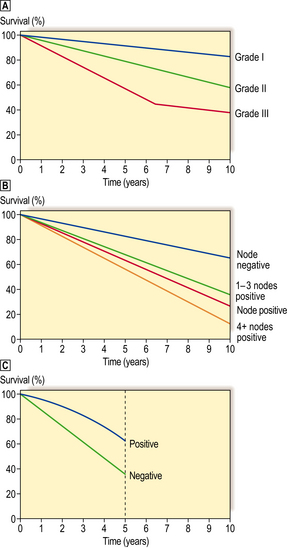

Examples of the effects some of these prognostic factors may have on survival are shown in Figure 18.29.

OTHER TUMOURS

Phyllodes tumours

Phyllodes tumours have two characteristic parts, epithelium and stroma. The epithelium covers large, club-like projections which push into cystic spaces. The stroma is much more cellular than that of fibroadenomas (Fig. 18.30) and can vary in type within the same tumour. The cells may resemble fibroblasts, or they may show marked pleomorphism with mitotic figures. In some tumours, the stromal changes are so marked that they have the appearances of sarcomas.

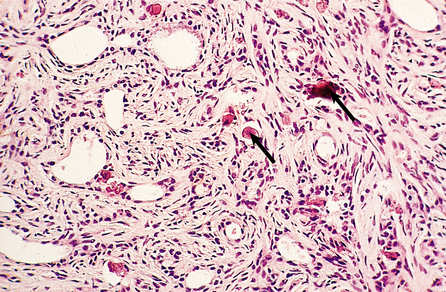

Angiosarcomas

Angiosarcomas are rare tumours that can occur at any time from adolescence to old age but are commoner in young women. Although most cases occur spontaneously, angiosarcomas can arise in irradiated mastectomy scars and in lymphoedematous arms after radical mastectomy for breast cancer (Stewart–Treves syndrome).

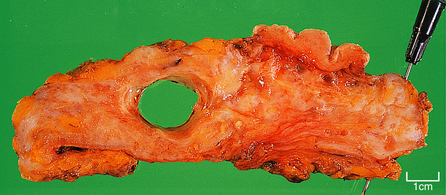

Angiosarcomas can present as a lump, or cause a diffuse enlargement of the breast. Discoloration of the overlying skin can be seen in some cases. Macroscopically, they can be haemorrhagic or appear as ill-defined areas of induration (Fig. 18.31).

Other sarcomas

Fibrosarcoma, liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma can all occur in the breast but are rare.

Lymphomas

Lymphomas may be primary, but are more usually secondary to disease elsewhere in the body.

Commonly confused conditions and entities relating to breast pathology

| Commonly confused | Distinction and explanation |

|---|---|

| Fibroadenoma and fibroadenosis | Fibroadenoma is a localised circumscribed benign neoplasm comprising epithelial cells and specialised fibrous tissue. Fibroadenosis is an obsolete name for fibrocystic change, a hyperplastic lesion. |

| Fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumour | Fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumour both comprise neoplastic epithelial and fibrous tissue components. However, in phyllodes tumours the fibrous tissue component is more cellular and abundant, and the lesion has less well defined margins; borderline and malignant variants occur. |

| Ductal epithelial hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ | Ductal epithelial hyperplasia is a benign proliferation of duct epithelium, whereas ductal carcinoma in situ has undergone neoplastic transformation, although it is not yet invasive. These lesions can have morphological similarities. A proportion share genetic alterations. |

| Radial scar and complex sclerosing lesion | Radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions differ only in size: the latter are >10 mm in diameter. Both mimic carcinomas radiologically and histologically, but they are benign non-neoplastic lesions. |

| Medullary carcinoma of the breast and of the thyroid | The term medullary refers only to the soft consistency (resembling the medulla of the brain). There is no other relationship between these lesions. |

| Paget’s disease of the nipple and of bone | Both lesions were described by Sir James Paget (1814–1899). There is no other relationship between these lesions. |

Dixon J.M.. ABC of breast diseases, 2nd edn. London: BMJ; 2000.

Elston C.W., Ellis I.O.. The breast. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Harris J.R., Morrow M., Lippman M.E. Diseases of the breast. 3rd edn 2004. Lippincott, Williams & Philadelphia: Wilkins

Nathanson K.L., Wooster R., Weber B.L.. Breast cancer genetics: what we know and what we need. Nature Medicine. 2000;7:552-556.

Rosen P.P. Rosen’s breast pathology. 2nd edn 2001. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

Sloane J.P.. Biopsy pathology of the breast, 2nd edn. London: Arnold; 2001.

World Health Organization. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of the breast and female genital tract. Lyons: IARC; 2003.

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org

Grade or degree of tumour differentiation (grade I = well differentiated; grade II = moderately differentiated; grade III = poorly differentiated). 10-year survival.

Grade or degree of tumour differentiation (grade I = well differentiated; grade II = moderately differentiated; grade III = poorly differentiated). 10-year survival.  Presence or absence of lymph node metastasis, and relationship to number of lymph nodes involved. 10-year survival.

Presence or absence of lymph node metastasis, and relationship to number of lymph nodes involved. 10-year survival.  Presence or absence of oestrogen receptor within the tumours. 5-year survival (less significant after this period).

Presence or absence of oestrogen receptor within the tumours. 5-year survival (less significant after this period).