CHAPTER 96 Brain Tumors

An Overview of Current Histopathologic Classifications

Astrocytomas

Diffuse Astrocytomas

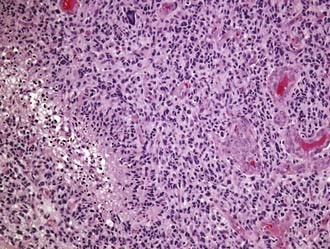

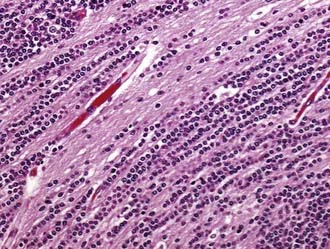

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; WHO grade IV) is unfortunately both the most common glioma and the most malignant primary brain tumor arising in adults. Most commonly, GBMs are solitary tumors of the cerebral hemispheres but may develop at almost any site within the neuraxis, including the cerebellum and the spinal cord. In many cases they infiltrate across the corpus callosum or arise directly within it, with bilateral extension (butterfly tumor). Multifocal tumors are observed in about 2% of patients and are often mistaken for metastatic disease on preoperative neuroimaging studies. The necrotic tumor mass may be partially delineated on gross examination, but infiltrating glioma cells can easily be identified microscopically well beyond the apparent gross tumor boundaries. The cellular morphology of GBM cells is highly variable, with the spectrum ranging from small, tightly packed, round or elongated cells to giant bizarre and multinucleated forms, all of which are frequently encountered within a single tumor. Mitotic figures are typically readily identified, and corresponding proliferation marker indices, such as the Ki-67 antigen, show elevated levels. Positive immunostaining for GFAP is characteristic but highly variable and can be absent in some instances. Microvascular proliferation and foci of necrosis are histologic hallmarks of GBM (Fig. 96-1). The presence of necrosis is not required for a diagnosis of GBM; vascular proliferation, in conjunction with pleomorphism and increased mitotic activity, is sufficient according to WHO 2007 criteria.

Oligodendroglial and Oligoastrocytic Glial Tumors

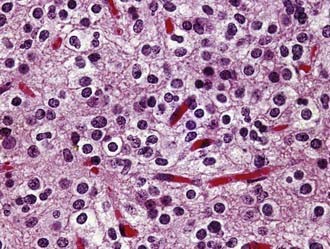

Oligodendroglioma (WHO grade II) is a well-differentiated, diffusely infiltrating tumor composed of cells resembling normal oligodendroglia. Most oligodendrogliomas arise in adults in the fourth and fifth decades. Their preferential location is the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres, from which tumor cells typically infiltrate the overlying cortex. As viewed macroscopically and on neuroimaging studies, oligodendrogliomas often appear somewhat more circumscribed than astrocytomas. They are composed of uniform round cells with cleared cytoplasm surrounding a central spherical nucleus (fried egg appearance). The perinuclear halo is a diagnostically useful fixation artifact present only in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue (Fig. 96-2). Mitotic activity is inconspicuous. A branching network of small delicate blood vessels (chicken wire pattern) is a classic histologic feature of many oligodendrogliomas. Microcalcifications are also common. Subpial tumor infiltration, perineuronal satellitosis, and perivascular satellitosis of tumor cells (secondary structures of Scherer) are characteristically seen in oligodendrogliomas that infiltrate gray matter. No oligodendroglioma-specific immunohistochemical markers are currently available. Oligodendrogliomas generally recur locally and ultimately undergo anaplastic progression.

Ependymal Tumors

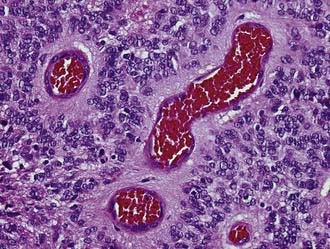

Ependymoma (WHO grade II) is a slowly growing neoplasm of children and young adults that originates from the ependymal lining of the cerebral ventricles. An infratentorial location is the most frequent in children, whereas in adults most of these tumors are supratentorial. Ependymomas may occur outside the ventricular system in the brain parenchyma and also in the spinal cord. Ependymomas are grossly characterized by a sharply demarcated edge. As seen histologically, classic ependymomas are moderately cellular tumors composed of oval cells with monomorphic nuclei and tapering eosinophilic cytoplasm. Some ependymomas have a more glial appearance, whereas others are more epithelioid. Some ependymoma variants (cellular, tanycytic) mimic other primary tumors, although others (papillary, clear cell) may mimic secondary tumors. The histologic hallmarks of ependymoma are the perivascular pseudorosette (perivascular collars of radiating tumor cell cytoplasmic processes) and, more elegantly but less frequent, the true ependymal rosette (tumor cells surrounding a central lumen) (Fig. 96-3). GFAP and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) immunopositivity is a frequent finding in ependymoma. GFAP reactivity is often strongest in the perivascular pseudorosettes, and EMA positivity takes the form of cytoplasmic dot-like and ring-like staining. Electron microscopy may be required in some cases to identify the ultrastructural features associated with ependymal cell differentiation (intercellular lumina filled with microvilli and sometimes cilia and prominent intercellular junctional complexes).

Neuronal and Mixed Neuronal-Glial Tumors

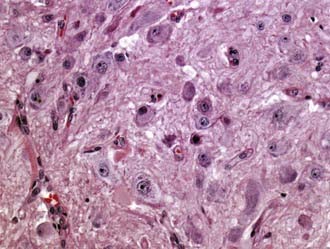

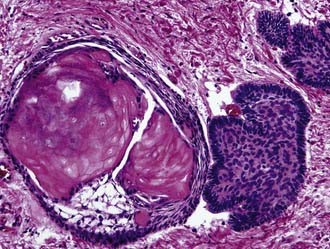

Gangliocytoma (WHO grade I) and ganglioglioma (WHO grade I or III) are well-differentiated tumors composed of neoplastic mature-appearing neurons alone (gangliocytoma) or neoplastic ganglion cells combined with glioma cells (ganglioglioma). They frequently occur in the temporal lobe. Ganglioglioma is the most common tumor associated with chronic temporal lobe epilepsy (40% of tumor-associated temporal lobe epilepsy cases). Both tumors are grossly circumscribed, may be solid or cystic, and frequently contain calcifications. At the microscopic level, gangliocytoma is composed entirely of clusters of dysmorphic mature ganglion cells (Fig. 96-4), whereas the ganglion cells in ganglioglioma are accompanied by glioma elements (usually astrocytoma). The glial component may include cell types resembling pilocytic astrocytoma (with Rosenthal fibers and EGBs), fibrillary astrocytoma, or rarely, oligodendroglioma. In the latter two cases, ganglioglioma has the potential to undergo anaplastic progression. Ganglioglioma must be differentiated from the cortical invasion of diffuse astrocytoma with entrapped neurons. Lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates are common. Immunopositivity for neuronal markers, such as synaptophysin and NeuN, in a subpopulation of tumor cells is characteristic. Another helpful marker is the oncofetal CD34 antigen, which is expressed in the neural component of gangliogliomas but not in normal brain.

Embryonal Tumors

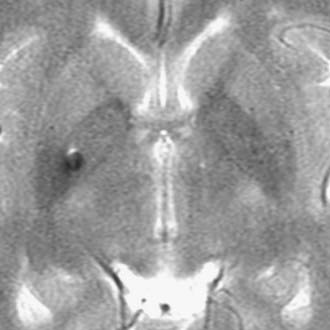

A closely related variant is the recently described MDB with extensive nodularity, which is rare, is seen only in infants, and displays a unique multinodular appearance that is apparent on preoperative imaging studies. As seen microscopically, this variant is characterized by large lobules of neuropil-like tissue with prominent streaming of neoplastic neurocytes and little or no extranodular tissue (Fig. 96-5).

Tumors of the Sellar Region (Excluding Pituitary Adenoma)

Craniopharyngioma (WHO grade I) is an epithelial tumor of the sellar and suprasellar regions, presumably derived from Rathke pouch remnants, that occurs predominantly in children and young adults. Two morphologic subtypes are distinguished: adamantinomatous, which is the most common, and papillary. The adamantinomatous subtype consists of cords and broad strands of squamous epithelium with peripheral palisading of basal cell nuclei, loosely adhesive areas of epithelium (stellate reticulum), and plump nodules of wet keratin that are prone to calcify (Fig. 96-6). Additional findings are cholesterol clefts, macrophages, and cyst formation. The cystic cavities characteristically contain a dark, viscous fluid that has been likened to machinery oil. Pilocytic astrocytosis with prominent Rosenthal fiber formation is frequently found in the compressed neuropil of the surrounding brain parenchyma. The papillary variant occurs only in adults, is usually well circumscribed, and is exclusively composed of nonkeratinizing well-differentiated squamous epithelium. The extent of surgical resection is the most significant factor associated with survival of patients with craniopharyngioma. Residual tumor will recur.

Adesina AM, Tihan T, Fuller CE, et al, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Brain Tumors. New York: Springer, 2009.

Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Tumors of the central nervous system. In: AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2007.

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th ed, Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007.

Perry A, Brat DB, editors. Practical Surgical Neuropathology. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2010.

Van Meir EG, editor. CNS Cancer: Models, Markers, Prognostic Factors, Targets, and Therapeutic Approaches. New York: Springer, 2009.