13 Brain Metastases

Incidence

The frequency of brain metastases reflects the incidence of primary malignancy as well as the propensity for CNS dissemination. Lung, breast, melanoma, renal, and colorectal cancers account for the majority of cases of brain metastases. The overall risk of developing brain metastases in patients with solid tumors is in the region of 10%. The reported incidence for patients with lung cancer is 20%, melanoma 7%, renal carcinoma 7%, breast cancer 5%, and colorectal cancer 2%. Patients with breast cancer aged 20 to 39 years have the highest proportional risk of brain metastases.1

Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients with brain metastases may present with the classical features of a brain tumor. In the presence of multiple lesions, the presentation may be with a nonspecific global deficit and confusional state or epilepsy. Although cognitive impairment is common, detected in up to 65% of patients,2 it requires detailed neuropsychological testing. Any patient with known malignant disease presenting with any features indicating an intracranial problem requires imaging with CT, or preferably MRI, with and without contrast.

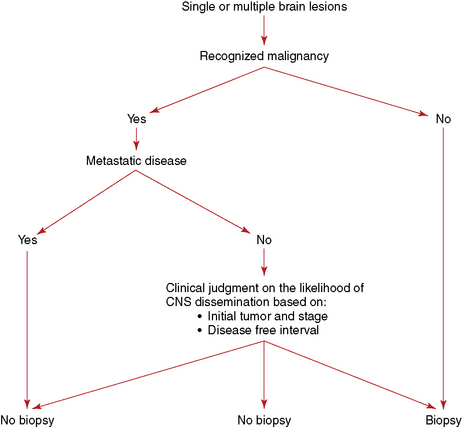

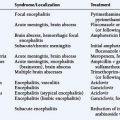

The need for a histological confirmation of metastatic disease in the brain is summarized in an algorithm (Figure 13-1). In the presence of known systemic malignancy and metastatic disease, there is no indication for biopsy of intracranial lesions unless there is a high index of suspicion for an alternative diagnosis such as an atypical infection. In patients presenting with lesions in the brain, without previous history of primary malignancy, histological confirmation of diagnosis is generally required, preferably from an extracranial site.

Prognosis

Patients with brain metastases have a limited prognosis, with few or no long-term survivors. Median survival in patients with multiple brain metastases is in the region of 3 to 4 months, and 1 year survival is in the region of 12%.3

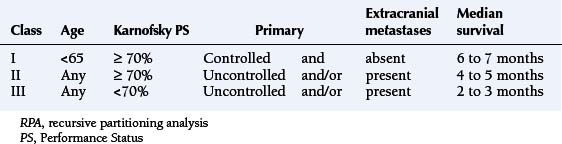

Prognostic factors for survival are performance status, age, and the presence and activity of systemic disease. Patients with all four favorable prognostic factors (Karnofsky Performance Status [KPS] >70, no extracranial metastases, controlled primary tumor, age under 65 years) have a median survival in the region of 7 months. In the presence of one adverse prognostic factor, the median survival drops to 4 months, and, if KPS score is below 70, the median survival is just over 2 months (Table 13-1).4 More recent prognostic indices also include the number of metastases, distinguishing between solitary lesions and the presence of two or three lesions or more than three.

Medical Management

The aim of treatment of brain metastases is palliation, to improve neurological deficit and quality of life and to prolong survival. Mass effect and neurological deficit assumed to be due to surrounding edema are appropriately treated with corticosteroids. Oral dexamethasone is generally employed as the drug of choice and can be administered in a single daily dose. The tendency has been to recommend a large loading dose followed by reduced daily doses, although it is not clear whether this approach leads to a faster improvement in function. The only regimen subject to a randomized trial is the administration of low-dose dexamethasone (4 mg daily) in comparison to high-dose dexamethasone (12 mg daily). The improvement in function at one week was the same regardless of dose. Patients receiving higher doses experienced more severe side effects,5 which suggests that 4 mg dexamethasone given in a single daily dose is sufficient and should only be increased in the absence of response after 2 or 3 days. In patients with clinical features of increased intracranial pressure, higher loading doses are recommended. After a clinical benefit has been achieved, the dose should be gradually titrated down to the lowest necessary to maintain improvement in symptoms. It is also important to reduce and discontinue corticosteroids after definitive treatment, to avoid cushingoid side effects.

The management of seizures in patients with brain metastases should be along the lines of management of epilepsy in patients with any brain tumor. There is no evidence for benefit of prophylactic anticonvulsants.6 If chemotherapy is part of the management (see below), it is preferable to avoid enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants that increase the metabolism of taxanes, anthracyclines, vinca alkaloids and small molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitors, leading to lower effective doses. Lamotrigine is a reasonable first choice as it does not induce liver enzymes.

Specific Treatment Modalities

SURGERY

Surgery is the appropriate treatment for accessible solitary brain metastases in noneloquent areas. The aim is complete tumor removal to obtain symptomatic relief of increased intracranial pressure or focal deficit from the tumor mass and to achieve local disease control. In patients with multiple brain metastases, surgical excision is generally not indicated, unless one large and easily accessible lesion is responsible for the majority of symptoms. Although resection of multiple brain metastases has been recommended by some authors, the apparent favorable survival seen in the reported cohorts is most likely due to patient selection rather than the efficacy of surgery.7,8

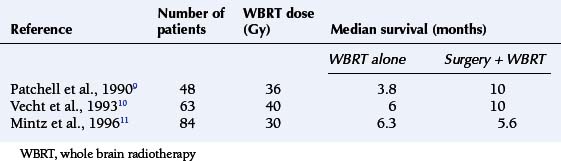

The survival benefit of surgical resection of solitary brain metastases has been tested in three small randomized trials comparing surgery and whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) with WBRT alone. Two studies had shown prolongation in survival, but this was not confirmed in the third study (Table 13-2).9,10,11 The consensus of opinion is that surgery is the appropriate treatment for patients with solitary brain metastases, with the aim being to prolong survival and improve quality of life (QoL). However, radical excision should be reserved for patients with favorable prognostic factors, particularly those without progressive systemic disease.

RADIOTHERAPY

Whole brain irradiation has been the mainstay of treatment of patients with brain metastases. Only one randomized trial compared supportive care (corticosteroids alone) with whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT); it showed a small improvement in median survival in patients receiving WBRT.12 Subsequent randomized studies examining the role of WBRT compared different dose fractionation schedules to identify the most effective regimen. None have shown benefit for more intensive treatment employing higher doses, given either as daily fractionation or as accelerated radiotherapy using multiple treatments per day. A UK study comparing 30 Gy in 10 fractions with 12 Gy in two fractions had shown a survival benefit for longer fractionation in favorable-prognosis patients,13 and one or two fraction regimens are rarely employed. The preferred WBRT for patients with multiple brain metastases is 20 Gy in 5 fractions, or 30 Gy in 10 fractions. WBRT improves neurological function in over half of patients with a deficit, although part of the improvement may be due to corticosteroids.

It is generally accepted that patients with good performance status and reasonable prognosis may benefit from WBRT both in terms of survival and neurological function/QoL. However, the value of radiotherapy in patients with marked disability and poor performance status is questioned,14 and at present it is not clear whether WBRT is appropriate. Randomized trials currently underway examine survival and quality of life benefits of WBRT in patients with multiple brain metastases and poor prognosis.

In diseases with a high incidence of intracranial dissemination of disease, brain irradiation may be used as prophylaxis, similar to the use of craniospinal irradiation in acute lymphatic leukemia in childhood. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) improves intracranial tumor control and survival in patients with limited and advanced-stage small cell lung cancer who achieve good remission with chemotherapy15,16; however, the magnitude of gain in life expectancy is not large and neurocognitive deficits in long-term survivors are of concern. So far there is not enough evidence to support PCI in patients with other solid tumors.

RADIOTHERAPY AND RADIOSENSITIZERS

A number of radiation sensitizers have been tested in addition to radiotherapy with the aim of improving disease control in the brain as well as survival. Electron-affinic sensitizers (metronidazole, misonidazole)17,18 and sensitizers of proliferating cells (BUdr)19 have not demonstrated benefit in randomized studies. The addition of radiation sensitizers motexafin gadolinium, which is preferentially taken up by enhancing lesions,20 and efaproxiral do not improve survival or disease control.

RADIOSURGERY

Radiosurgery (stereotactic radiotherapy) is a high-precision localized radiation which can be delivered with a linear accelerator (using multiple fixed fields or multiple arcs of rotation) or with a multiheaded cobalt unit (gamma knife). Stereotactic radiotherapy delivers more localized radiation than would be achieved with conventional irradiation for lesions less than 4 cm in diameter.21

Radiosurgery has been considered as a noninvasive equivalent of surgical excision, although the apparent equivalence of tumor control and survival is based on reported data from largely retrospective phase II studies.22

Following a single radiation dose (radiosurgery) of 15 to 25 Gy, the “response rate,” measured as a reduction in the size of solitary metastases, is in the range of 80% to 90%, although complete disappearance is uncommon. In patients with MRI-proven solitary brain metastases the addition of radiosurgery to whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) improves survival and tumor control.23 Radiosurgery does not prolong survival in patients with multiple (two or more) brain metastases.23

The prognostic factors for survival in patients with solitary brain metastases are the same as in patients with multiple brain metastases.24 The dominant adverse prognostic factor for survival is performance status.25 Patients with poor performance status and marked disability have survival similar to patients with multiple brain metastases, and radiosurgery is not appropriate as first-line palliative treatment.

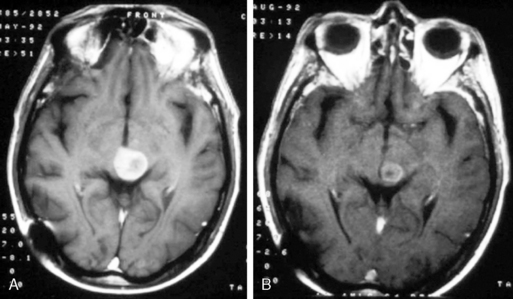

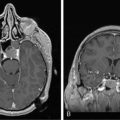

The present recommendation is to offer radiosurgery to patients with solitary brain metastases and good performance status. While it is generally reserved for patients with surgically inaccessible lesions, it can be considered as an alternative to surgery and therefore can be offered as an alternative to surgical excision even in operable lesions. It is a less invasive, less costly, and largely outpatient procedure (Figure 13-2). Radiosurgery can occasionally be offered to selected patients with two (or rarely three) metastases, good performance status, and absent or controlled systemic disease.

The role of WBRT following surgery or radiosurgery is currently debated. One small randomized study has shown that the addition of WBRT prolongs intracranial disease control. This was not translated into survival benefit and the overall value of adding WBRT is not clear.26 A large prospective randomized trial addressing this question is underway. Our institutional policy is not to offer WBRT to patients following successful local treatment, and to continue close monitoring with repeat imaging (e.g., every 3 months). Routine addition of WBRT is an alternative approach. Patients considered for radiosurgery as primary treatment often have initial WBRT as rapid initial therapy, allowing time for more technologically-intensive radiosurgery.

SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

Chemotherapy does not prevent the development of brain metastases, as adjuvant chemotherapy in lung and breast cancer27,28 does not reduce the incidence of brain metastases. The response rate of brain metastases to chemotherapy tends to reflect the responsiveness of the malignancy outside the brain.29,30,31 Decision on the use of systemic agents should therefore be based on the assessment of chemosensitivity of the disease. In patients with brain metastases from untreated chemosensitive tumors such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and germ cell tumors, the appropriate first-line treatment is chemotherapy. In other solid tumors, clinical data on the efficacy of chemotherapy as the sole treatment for brain metastases are mostly limited to small phase II studies, often in heavily pretreated patients, which provide limited information on the choice of agents.

Chemotherapy has been considered as an additional treatment to WBRT in patients with established brain metastases. Randomized phase II studies of concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide, teniposide or other drugs with radiation show no survival benefit and at best a small difference in response rate and progression-free survival.32

Management in Common Solid Tumors

NON–SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER (NSCLC)

The actuarial 2-year cumulative risk of developing brain metastases in patients with locally advanced stage III adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma following combined modality treatment is 22% and 10% respectively, and nearly half present within 4 months of completion of treatment.27 While the use of chemotherapy reduces the risk of extracranial failure, it has no effect on the incidence of CNS relapse. PCI has been suggested in patients with locally advanced NSCLC. It may reduce the risk of developing disease in the brain, but the overall benefit is yet to be defined.33

Patients with brain metastases from NSCLC tend to be heavily pretreated and have less chance of responding to second-line or third-line agents; they should, therefore, receive short palliative WBRT. The response rates to platinum-based chemotherapy as a preferred first-line regimen are similar to those in systemic NSCLC. In asymptomatic chemonaïve patients not in need of immediate radiotherapy, chemotherapy can therefore be considered as an alternative, particularly in the presence of disseminated or locally advanced and progressive disease, with radiotherapy reserved for progressive intracranial disease.34 Temozolomide, an alkylating agent with good CNS penetration, has no single agent activity in NSCLC35 and has little role in patients with NSCLC brain metastases.

Tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), have activity in patients with brain metastases,36,37 similar to that seen with extracranial disease. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors such as bevacizumab and small-molecule TK receptor-inhibitors such as sorafenib and sunitinib are currently under investigation. Additional benefit from antiangiogenesis agents is postulated by their ability to reduce peritumoral edema, with the hope of reducing steroid dependence.

SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER (SCLC)

The incidence of brain metastases is particularly high in SCLC. In patients with limited disease who achieve complete or good remission, PCI has become part of the initial treatment. It decreases the incidence of brain metastases and has a modest survival benefit.15 Even in responding patients with extensive disease, PCI reduces the incidence of brain metastases and improves survival, albeit at the cost of some toxicity.16 Although there is concern regarding the impact of PCI on QoL and cognitive function, there are no consistent differences between patients with or without PCI, and no major impairment attributable solely to PCI.33,38,39

Intracranial metastases from SCLC respond to chemotherapy as disease at other sites. In newly diagnosed (chemonaïve) patients with SCLC, the response of brain metastases to chemotherapy (without irradiation) is 70% to 80%, while at relapse (pretreated group) it is 40% to 50%.29 The use of additional WBRT does not translate into improved survival, suggesting that extracranial disease is the major determinant of outcome40 in this group of patients.

BREAST CANCER

Because of the high incidence of the disease, nearly a quarter of patients presenting with brain metastases have underlying breast cancer. The risk of developing brain metastases is higher in younger patients who have negative estrogen receptor status, grade 3 disease, large tumors and HER-2 overexpression, and is also more common in the presence of visceral metastases, especially lung.41,42 Patients with HER-2−overexpressing tumors are more prone to developing brain metastases, and the incidence is not reduced by the HER-2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. Dual EGFR and HER-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib, which penetrates the BBB, has not, so far, shown improved efficacy.

Breast cancer is both chemoresponsive and radioresponsive. There are no randomized trials comparing the two treatment modalities. WBRT remains the standard of care in the majority of symptomatic patients. Patients with brain metastases who have chemosensitive tumors, particularly with metastatic disease at other sites, can be considered for systemic chemotherapy, and, if they have hormone responsive disease, for hormone therapy. Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine has shown activity in the brain,43,44 while temozolomide has minimal activity and is unlikely to be effective for brain metastases.

MALIGNANT MELANOMA

While response rates to single agent dacarbazine (DTIC), temozolomide (TMZ), and fotemustine are 5% to 15%, in the brain they are only around 7%.45,46 Although a more aggressive approach with platinum and DTIC combined with IL-2 and interferon may result in marginally better response rates (and occasional complete response) outside the brain, it does not prevent the development of brain metastases. A phase III randomized trial comparing fotemustine with DTIC in patients with disseminated melanoma suggested a longer median time to developing brain metastases (22.7 vs. 7.2 months), although this did not reach statistical significance (p= .059).47 Replacing DTIC with temozolomide has been claimed to reduce the incidence of CNS progression, but did not result in improved survival.48 The addition of thalidomide to temozolomide in metastatic melanoma has also not altered the incidence of brain metastases, but has added to toxicity.49

GERM CELL TUMORS

Approximately 10% of all patients with advanced gonadal germ cell tumors present with brain metastases. CNS disease may also appear as part of systemic relapse. The primary treatment in patients with brain metastases is chemotherapy, as in advanced nonseminoma germ cell tumors. Despite a high response rate to chemotherapy, radiotherapy (WBRT) is recommended as adjuvant treatment.50,51

1. J.S. Barnholtz-Sloan, A.E. Sloan, F.G. Davis, F.D. Vigneau, P. Lai, R.E. Sawaya. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865-2872.

2. E.L. Chang, J.S. Wefel, M.H. Maor, S.J. Hassenbusch, A. Mahajan, F.F. Lang, et al. A pilot study of neurocognitive function in patients with one to three new brain metastases initially treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:277-283.

3. F.J. Lagerwaard, P.C. Levendag, P.J. Nowak, W.M. Eijkenboom, P.E. Hanssens, P.I. Schmitz. Identification of prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases: a review of 1292 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43(4):795-803.

4. L.E. Gaspar, C. Scott, K. Murray, W. Curran. Validation of the RTOG recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) classification for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(4):1001-1006.

5. C.J. Vecht, G.L. Wagner, E.B. Wilms. Interactions between antiepileptic and chemotherapeutic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(7):404-409.

6. M.J. Glantz, B.F. Cole, P.A. Forsyth, L.D. Recht, P.Y. Wen, M.C. Chamberlain, et al. Practice parameter: anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;54(10):1886-1893.

7. R.K. Bindal, R. Sawaya, M.E. Leavens, J.J. Lee. Surgical treatment of multiple brain metastases. J Neurosurg. 1993;79(2):210-216.

8. M. Wronski, E. Arbit, M. Burt, J.H. Galicich. Survival after surgical treatment of brain metastases from lung cancer: a follow-up study of 231 patients treated between 1976 and 1991. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(4):605-616.

9. R.A. Patchell, P.A. Tibbs, J.W. Walsh, R.J. Dempsey, Y. Maruyama, R.J. Kryscio, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494-500.

10. C.J. Vecht, H. Haaxma Reiche, E.M. Noordijk, G.W. Padberg, J.H.C. Voormolen, F.H. Hoekstra, et al. Treatment of single brain metastasis: Radiotherapy alone or combined with neurosurgery? Ann Neurol. 1993;33:583-590.

11. A.H. Mintz, J. Kestle, M.P. Rathbone, L. Gaspar, H. Hugenholtz, B. Fisher, et al. A randomised trial to assess the efficacy of surgery in addtion to radiotherapy in patients with a single cerebral metastasis. Cancer. 1996;78:1470-1476.

12. J. Horton, D.H. Baxter, K.B. Olson. The management of metastases to the brain by irradiation and corticosteroids. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1971;111(2):334-336.

13. T.J. Priestman, J. Dunn, M. Brada, R. Rampling, P.G. Baker. Final results of the Royal College of Radiologists’ trial comparing two different radiotherapy schedules in the treatment of cerebral metastases. Clin Oncol R Coll Radiol. 1996;8(5):308-315.

14. M.N. Tsao, K. Sultanem, D. Chiu, F. Copps, P. Dixon, D. Easton, et al. Supportive care management of brain metastases: what is known and what we need to know. Conference proceedings of the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) Workshop on Symptom Control in Radiation Oncology. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2003;15(7):429-434.

15. A. Auperin, R. Arriagada, J.P. Pignon, C. Le Pechoux, A. Gregor, R.J. Stephens, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(7):476-484.

16. B. Slotman, C. Faivre-Finn, G. Kramer, E. Rankin, M. Snee, M. Hatton, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(7):664-672.

17. H.J. Eyre, J.D. Ohlsen, J. Frank, A.F. LoBuglio, J.D. McCracken, T.J. Weatherall, et al. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus radiotherapy plus metronidazole for the treatment metastatic cancer to brain. A Southwest Oncology Group study. J Neurooncol. 1984;2(4):325-330.

18. L.T. Komarnicky, T.L. Phillips, K. Martz, S. Asbell, S. Isaacson, R.A. Urtasun, et al. protocol for the evaluation of misonidazole combined with radiation in the treatment of patients with brain metastases (RTOG-7916). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20(1):53-58.

19. T.L. Phillips, C.B. Scott, S.A. Leibel, M. Rotman, I.J. Weigensberg. Results of a randomized comparison of radiotherapy and bromodeoxyuridine with radiotherapy alone for brain metastases: report of RTOG trial 89–05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33(2):339-348.

20. M.P. Mehta, P. Rodrigus, C.H. Terhaard, A. Rao, J. Suh, W. Roa, et al. Survival and neurologic outcomes in a randomized trial of motexafin gadolinium and whole-brain radiation therapy in brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(13):2529-2536.

21. M. Brada, T. Foord. Radiosurgery for brain metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2002;14(1):28-30.

22. A. Pirzkall, J. Debus, F. Lohr, M. Fuss, B. Rhein, R. Engenhart Cabillic, et al. Radiosurgery alone or in combination with whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3563-3569.

23. D.W. Andrews, C.B. Scott, P.W. Sperduto, A.E. Flanders, L.E. Gaspar, M.C. Schell, et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9422):1665-1672.

24. S. Milker-Zabel, J. Debus, C. Thilmann, W. Schlegel, M. Wannenmacher. Fractionated stereotactically guided radiotherapy and radiosurgery in the treatment of functional and nonfunctional adenomas of the pituitary gland. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(5):1279-1286.

25. R. Jyothirmayi, F.H. Saran, R. Jalali, J. Perks, A. Warrington, S. Ashley, et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy for solitary brain metastases. Clin Oncol. 2001;13:228-234.

26. R.A. Patchell, P.A. Tibbs, W.F. Regine, R.J. Dempsey, M. Mohiuddin, R.J. Kryscio, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485-1489.

27. L.E. Gaspar, K. Chansky, K.S. Albain, E. Vallieres, V. Rusch, J.J. Crowley, et al. Time from treatment to subsequent diagnosis of brain metastases in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective review by the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2955-2961.

28. D. Crivellari, O. Pagani, A. Veronesi, D. Lombardi, F. Nole, B. Thurlimann, et al. High incidence of central nervous system involvement in patients with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer treated with epirubicin and docetaxel. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(3):353-356.

29. C.A. Kristensen, P.E.G. Kristjansen, H.H. Hansen. Systemic chemotherapy of brain metastases from small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1498-1502.

30. G. Bernardo, Q. Cuzzoni, M.R. Strada, A. Bernardo, G. Brunetti, I. Jedrychowska, et al. First-line chemotherapy with vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and carboplatin in the treatment of brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(3):293-302.

31. W. Boogerd, O. Dalesio, E.M. Bais, J.J. Sade. Response of brain metastases from breast cancer to systemic chemotherapy. Cancer. 1992:927-980.

32. E. Verger, M. Gil, R. Yaya, N. Vinolas, S. Villa, T. Pujol, et al. Temozolomide and concomitant whole brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastases: a phase II randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(1):185-191.

33. C. Pöttgen, W. Eberhardt, A. Grannass, S. Korfee, G. Stüben, H. Teschler, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in operable stage IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: Results from a german multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4987-4992.

34. G. Robinet, P. Thomas, J.L. Breton, H. Lena, S. Gouva, G. Dabouis, et al. Results of a phase III study of early versus delayed whole brain radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin and vinorelbine combination in inoperable brain metastasis of non-small-cell lung cancer: Groupe Francais de Pneumo-Cancerologie (GFPC) Protocol 95–1. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(1):59-67.

35. R. Dziadziuszko, A. Ardizzoni, P.E. Postmus, E.F. Smit, A. Price, C. Debruyne, et al. Temozolomide in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer with and without brain metastases. a phase II study of the EORTC Lung Cancer Group (08965). Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(9):1271-1276.

36. G.L. Ceresoli, F. Cappuzzo, V. Gregorc, S. Bartolini, L. Crino, E. Villa. Gefitinib in patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective trial. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1042-1047.

37. K. Hotta, K. Kiura, H. Ueoka, M. Tabata, K. Fujiwara, T. Kozuki, et al. Effect of gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) on brain metastases in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;46(2):255-261.

38. A. Gregor, A. Cull, R.J. Stephens, J.A. Kirkpatrick, J.R. Yarnold, D.J. Girling, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation is indicated following complete response to induction therapy in small cell lung cancer: results of a multicentre randomised trial. United Kingdom Coordinating Committee for Cancer Research (UKCCCR) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) [see comments]. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(11):1752-1758.

39. R. Arriagada, T. Le Chevalier, F. Borie, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:183-190.

40. P.E. Postmus, H. Haaxma-Reiche, E.F. Smit, H.J. Groen, H. Karnicka, T. Lewinski, et al. Treatment of brain metastases of small-cell lung cancer: comparing teniposide and teniposide with whole-brain radiotherapy—a phase III study of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(19):3400-3408.

41. A.M. Gonzalez-Angulo, M. Cristofanilli, E.A. Strom, A.U. Buzdar, S.W. Kau, K.R. Broglio, et al. Central nervous system metastases in patients with high-risk breast carcinoma after multimodality treatment. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1760-1766.

42. K. Slimane, F. Andre, S. Delaloge, A. Dunant, A. Perez, J. Grenier, et al. Risk factors for brain relapse in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1640-1644.

43. M.L. Wang, W.K. Yung, M.E. Royce, D.F. Schomer, R.L. Theriault. Capecitabine for 5-fluorouracil-resistant brain metastases from breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24(4):421-424.

44. N. Siegelmann-Danieli, M. Stein, J. Bar-Ziv. Complete response of brain metastases originating in breast cancer to capecitabine therapy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5(11):833-834.

45. M.R. Middleton, J.J. Grob, N. Aaronson, G. Fierlbeck, W. Tilgen, S. Seiter, et al. Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):158-166.

46. S.S. Agarwala, J.M. Kirkwood, M. Gore, B. Dreno, N. Thatcher, B. Czarnetski, et al. Temozolomide for the treatment of brain metastases associated with metastatic melanoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2101-2107.

47. M.F. Avril, S. Aamdal, J.J. Grob, A. Hauschild, P. Mohr, J.J. Bonerandi, et al. Fotemustine compared with dacarbazine in patients with disseminated malignant melanoma: A phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1118-1125.

48. M.B. Atkins, J.A. Gollob, J.A. Sosman, D.F. McDermott, L. Tutin, P. Sorokin, et al. A phase II pilot trial of concurrent biochemotherapy with cisplatin, vinblastine, temozolomide, interleukin 2, and IFN-alpha 2B in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(10):3075-3081.

49. W.J. Hwu, S.E. Krown, J.H. Menell, K.S. Panageas, J. Merrell, L.A. Lamb, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide plus thalidomide for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3351-3356.

50. H.J. Schmoll, R. Souchon, S. Krege, P. Albers, J. Beyer, C. Kollmannsberger, et al. European consensus on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG). Ann Oncol. 2004;15(9):1377-1399.

51. W. Spears. Brain metastases and testicular tumors: long term survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;22:17-22.