64 Brachial and Lumbosacral Plexopathies

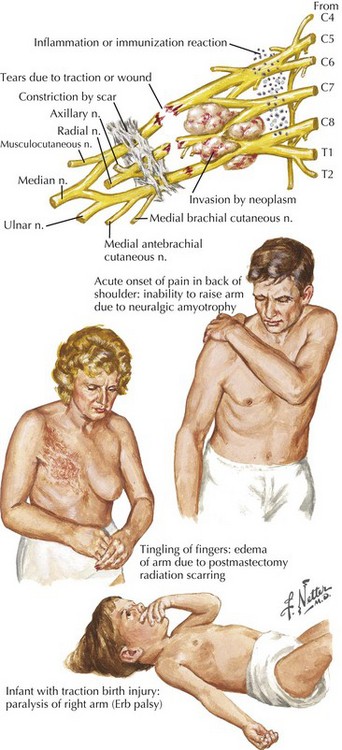

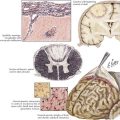

The most important diagnostic tool for the evaluation of a possible plexopathy is a thorough and accurate history. The history-taking must be aided by a solid understanding of the risk factors for development of brachial or lumbosacral plexopathy. The most common etiologies of plexopathy are trauma, surgery (e.g., related to arm or leg positioning, injury with regional anesthetic block), birth injury, inherited genetic mutations (e.g., hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy), a primary autoimmune process (e.g., Parsonage–Turner, also known as neuralgic amyotrophy), previous radiotherapy, and neoplastic invasion (Fig. 64-1; Table 64-1). Systemic vasculitis and peripheral nerve sarcoidosis are other uncommon etiologies. Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for an immune-mediated lumbosacral (and less often, brachial) plexopathy, that is, diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy (diabetic LRPN) secondary to microvasculitis. Thus, if a prior or concomitant history of any of these risk factors (e.g., previous surgery, trauma, or family history, diabetes) is present, the clinician should strongly consider that etiology yet not necessarily forget to consider other plausible etiologies. It is also helpful to remember that recent infection, vaccination, and parturition are triggers for the immune-mediated plexopathies, especially brachial plexopathies (e.g., hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy and neuralgic amyotrophy). There are often other clues about etiology found in the symptomatology of the plexopathy. For example, the abrupt, spontaneous onset of shoulder and upper extremity symptoms favors an immune-mediated (e.g., microvasculitic) mechanism, such as that seen with hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy, neuralgic amyotrophy and diabetic cervical radiculoplexus neuropathy (diabetic CRPN), whereas a more gradual or insidious onset of symptoms would point toward neoplastic invasion or postradiotherapy plexopathy. Immune-mediated plexopathies (e.g., diabetic LRPN or neuralgic amyotrophy) usually begin with severe pain, lasting days to weeks, followed by the development of weakness a few days to a few weeks later. Radiation-associated plexopathy (e.g., for breast cancer) usually presents with much less pain than plexopathy due to malignancy or due to immune-mediated mechanism. Radiation-induced brachial or lumbosacral plexopathy usually presents more gradually and can occur months to decades after radiotherapy. Recurrent, painful brachial plexopathy is most typical of hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy. The recognition of accompanying symptoms is also important. For example, weight loss is a common accompaniment of diabetic LRPN or diabetic CRPN, as well as plexopathies secondary to neoplasm or a more systemic process such as vasculitis.

Table 64-1 Brachial Plexus Etiologies

| Mechanism | Examples | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma, traction | Motorcycle injury, cardiothoracic surgery | Often severe degree, poor prognosis |

| Stinger | Football etc. | Good prognosis |

| Perinatal | Mixed mechanisms | Generally good prognosis |

| Idiopathic | Autoimmune? | Self-limited |

| Hereditary | Genetically determined | Recurrent, benign |

| Malignancy | Infiltration of tumor cells | Poor prognosis |

| Radiation | RoRx-induced ischemia | Prognosis guarded but not suggestive of recurrent tumor |

| Knapsack, rucksack, etc | Compression | Usually self-limited |

| Thoracic outlet | Entrapment | Rare, confused with CTS |

| Heroin induced | Indeterminate |

CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome; RoRx, radiation therapy.

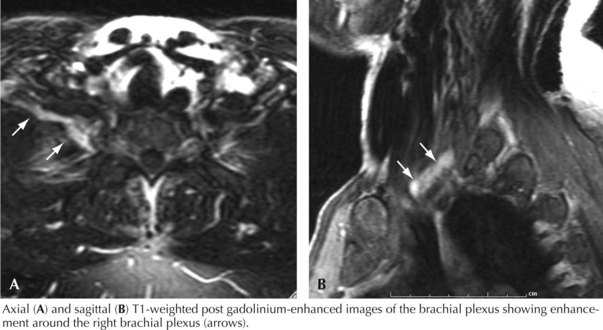

In the case presented above, the temporal evolution was of an abrupt-onset neuropathic process that caused motor and sensory dysfunction. The neuropathic process involved one lower extremity. The pain was so severe that the patient required narcotics. The patient had not experienced antecedent trauma, surgery, or radiotherapy. There was no family history of plexopathy. These factors suggested that an immune-mediated plexopathy was likely. Furthermore, the clinical setting was remarkable for diabetes mellitus and significant weight loss, and as diabetes mellitus is believed to be a risk factor for immune-mediated plexopathy and many of these patients experience contemporaneous weight loss, this diagnosis was most likely. Thus, the most likely etiology in this patient was DLRPN. Additional evaluation, including examination, electrodiagnostic testing and imaging, further supported the diagnosis (Fig. 64-2).

Anatomy

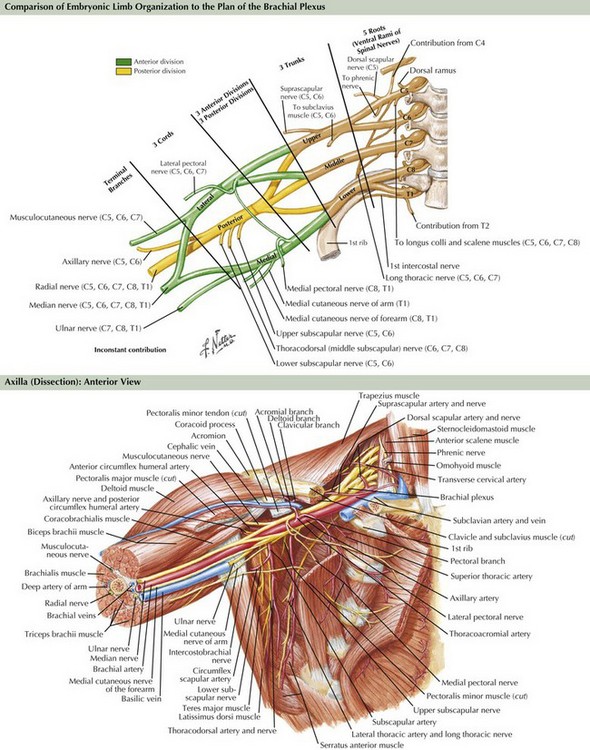

Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus is formed from the ventral rami of cervical roots 5–8 and thoracic root 1 (Fig. 64-3). The ventral rami of the fifth and sixth cervical roots together form the upper trunk, the seventh cervical root ventral ramus becomes the middle trunk, and the eighth cervical and first thoracic root ventral rami join to become the lower trunk. The trunks of the brachial plexus are located above the clavicle between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius muscles, in the posterior triangle of the neck, posterior and lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The dorsal scapular, long thoracic, and suprascapular nerves originate from the brachial plexus above the clavicle. Behind the clavicle and in front of the first rib, each trunk separates into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks unite to become the lateral cord, whereas the anterior division of the lower trunk forms the medial cord. The posterior divisions of all three trunks unite to become the posterior cord. The three cords are named for their positions relative to the axillary artery. Below the clavicle, the upper extremity nerves arise from the cords. From the lateral cord arises the musculocutaneous, the lateral head of the median, and the lateral pectoral nerves. From the medial cord comes the ulnar, the medial head of the median, the medial pectoral, and the medial brachial and medial antebrachial nerves. From the posterior cord arise the radial, axillary, subscapular, and thoracodorsal nerves.

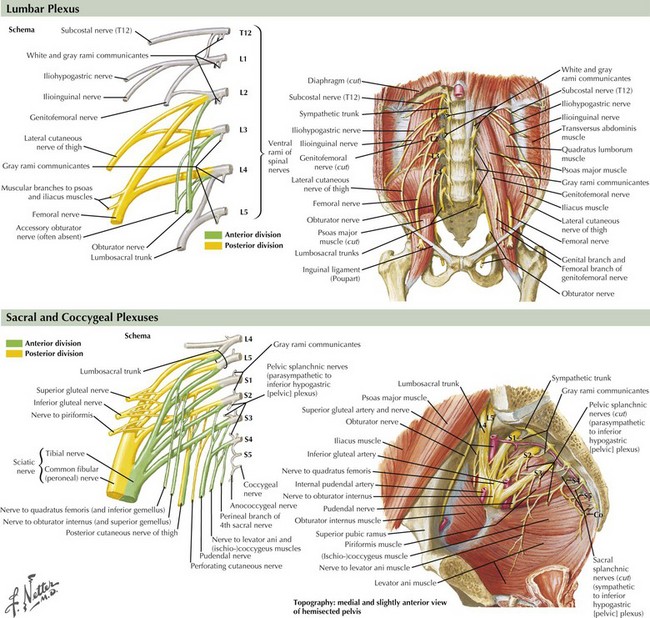

Lumbosacral Plexus

The femoral nerve, innervating the iliopsoas and the quadriceps femoris muscles, is the predominant derivative of the lumbar portion of the lumbosacral plexus (Fig. 64-4). Its sensory supply includes the anterior and lateral thigh, and the medial foreleg as the saphenous nerve. The obturator nerve innervating the adductor magnus also originates from the lumbar plexus. The sacral portion of the lumbosacral plexus innervates the remainder of the lower extremity muscles, including posterior thigh and buttocks muscles and all leg musculature below the knee. The superior and inferior gluteal nerves, the most proximal nerves originating from the sacral derivative of the lumbosacral plexus, innervate the gluteal muscles (medius, minimus, and maximus). The sciatic nerve innervates the hamstring group and bifurcates into the peroneal and tibial nerves, providing all motor innervation below the knee. The sciatic nerve provides sensory innervation to the posterior thigh and the entire leg below the knee, with the exception of the medial foreleg, which is supplied only by the saphenous nerve. The peroneal nerve is derived from the lateral portion of the sciatic nerve within the thigh; it supplies only one muscle above the knee, the short head of the biceps femoris. This site provides a means to differentiate electrodiagnostically atypical proximal peroneal or sciatic nerve lesions from common peroneal nerve compression or entrapment syndromes at the fibular head. The peroneal nerve bifurcates into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves, the latter innervating all anterior compartment muscles. The superficial peroneal motor nerve supplies the lateral compartment. The tibial nerve, the other primary sciatic nerve derivative, supplies the calf. The superficial peroneal sensory, the sural, and the medial and lateral plantar nerves are the primary superficial sensory nerves below the knee, in addition to the saphenous.

Differential Diagnosis

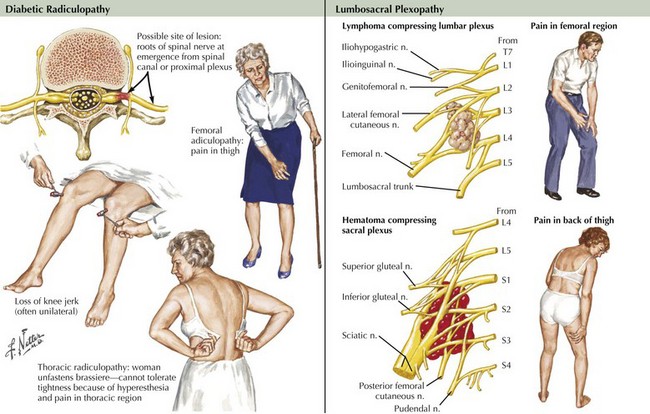

DLRPN is the most common cause of lumbosacral plexopathy (Fig. 64-5). DLRPN typically presents in older patients who have type 2 diabetes mellitus, with abrupt or subacute onset of hip and thigh severe pain (see case presentation above). Weakness and muscle atrophy occur within a week or two, often at the time the pain begins to improve. Muscle stretch reflexes may be lost, especially at the knee. DLRPN often begins unilaterally but frequently progresses to bilateral involvement. This monophasic disorder is usually significantly disabling and is commonly associated with unexplained weight loss. Like neuralgic amyotrophy, DLRPN is thought to originate from peripheral nerve microvasculitis. Idiopathic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy (LRPN) is a rare primary plexopathy that occurs in nondiabetics. It is also manifested by rapid onset of pain, leg weakness, and atrophy. Patients often experience a viral illness 1–2 weeks before symptoms begin. Lumbar plexus involvement often affects the most proximal musculature, causing weakness of the iliopsoas, quadriceps, and adductor muscles. Often, significant recovery occurs within 3 months.

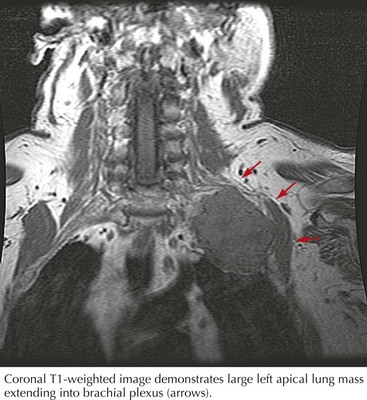

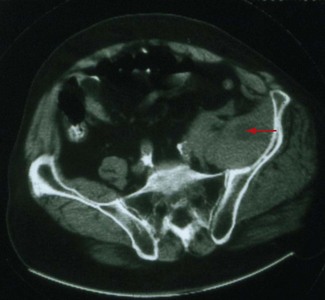

Malignant tumors, particularly apical lung or postradiation breast cancer, are common causes of brachial plexus lesions (Fig. 64-6). With apical lung tumors, the lesion may insidiously advance, causing numbness in the fourth and fifth fingers, weakness in the ulnar and median hand intrinsic muscles, and Horner syndrome (Pancoast tumor). Often, pain is significant, secondary to neoplastic infiltration of the brachial plexus. This clinical constellation sometimes precedes recognition of the lung tumor. Every patient who smokes and presents in this fashion requires a chest CT or MRI. Tumors occasionally invade the lumbosacral plexus by primary extension from pelvic, abdominal, or retroperitoneal malignancies (see Fig. 64-5). Pain in the distribution of the affected nerves is the cardinal symptom. Late symptoms and signs may include numbness and paresthesias, weakness and gait abnormalities, and lower extremity edema. Retroperitoneal hematomas can compress the lumbar or sacral plexuses or both. Patients present with unilateral pelvic or groin pain; the patient preferentially has the hip flexed to minimize pressure on the plexus (Fig. 64-7). This condition is typically a complication of anticoagulation therapy, or less commonly bleeding diatheses, and immediate surgical decompression can be beneficial.

Dyck PJ, Norell JE, Dyck PJ. Microvasculitis and ischemia in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Neurology. 1999;53:2113-2121.

Dyck PJ, Norell JE, Dyck PJ. Non-diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy: natural history, outcome and comparison with the diabetic variety. Brain. 2001;124:1197-1207.

Ferrante MA. Brachial plexopathies: classification, causes, and consequences. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:547-568.

Lederman RJ, Wilbourn AJ. Postpartum neuralgic amyotrophy. Neurology. 1996;47:1213-1219.

Moghekar AR, Moghekar AB, Karli N, et al. Brachial plexopathies. Etiology, frequency and electrodiagnostic localization. J Clin Neuromusc Dis. 2007;9:243-247.

Parsonage MJ, Turner JWA. Neuralgic amyotrophy. The shoulder-girdle syndrome. Lancet. 1948:973-978.

Rubin DI. Diseases of the plexus. Continuum. 2008;14:156-181.

Suarez GA, Giannini C, Bosch EP, et al. Immune brachial plexus neuropathy: suggestive evidence for an inflammatory immune pathogenesis. Neurology. 1996;46:559-561.

Triggs W, Young MS, Eskin T, et al. Treatment of idiopathic lumbosacral plexopathy with intravenous immunoglobulin. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:244-246.

Tsairis P, Dyck PJ, Mulder DW. Natural history of brachial plexus neuropathy. Report on 99 patients. Arch Neurol. 1972;27:109-117.

Van Alfen N. The neuralgic amyotrophy consultation. J Neurol. 2007;254:695-704.

Van Alfen N, van Engelen BGM. The clinical spectrum of neuralgic amyotrophy in 246 cases. Brain. 2006;129:438-450.

Verma A, Bradley WB. High dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in chronic progressive lumbosacral plexopathy. Neurology. 1994;44:248-250.