Bone266

25.2 Joints270

25.3 Connective tissue diseases274

Within the osteoarticular system, the bones provide structural support for the body and have an important role in mineral homeostasis and haematopoiesis, and the joints permit movement. Disorders of the osteoarticular system can, therefore, cause significant disability and deformity. Most of the more common disorders such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis are chronic and progressive, causing significant morbidity among the general population, especially the elderly. Bone tumours affect all age groups, show marked diversity in their behaviour and different types target particular age groups and anatomic sites. Connective tissue diseases form an important group of multisystem disorders, and they are presented here because a feature common to most of them is their propensity to involve the joints and soft tissues. ‘Soft tissue tumours’ form a highly heterogeneous group of neoplasms that are important because benign tumours are relatively frequent and sarcomas are often highly aggressive.

25.1. Bone

Structure and function

The skeletal system is composed of 206 bones, and has a number of functions:

• Structural support.

• Protective. The skull and the vertebral column protect the brain and spinal cord respectively. The ribs protect the thoracic and upper abdominal organs to a lesser degree.

• Mineral homeostasis. Bone is a reservoir for the body’s calcium, phosphorus and magnesium.

• Haematopoiesis. Under normal conditions in the adult, bone is the sole site of haematopoietic marrow.

Bone is a special type of connective tissue, which is mineralised, and therefore has an organic and inorganic component. The organic component is the connective tissue matrix composed predominantly of type I collagen. The organic matrix undergoes mineralisation by the deposition of the mineral calcium hydroxyapatite. This mineral is the inorganic component of bone. Mineralisation gives bone its strength and hardness. Unmineralised bone is called osteoid. Bone formation, maintenance and remodelling is performed by the bone cells, of which there are three main types:

• Osteoblasts – these cells are responsible for bone formation. They synthesise the type I collagen that forms osteoid, and also initiate the process of mineralisation.

• Osteoclasts – these are multinucleate cells responsible for bone resorption.

• Osteocytes – evidence suggests that these cells have an important role in the control of the daily fluctuations in serum calcium and phosphorus levels and the maintenance of bone.

Bone can be formed quickly or slowly. When bone is formed quickly, such as in fracture repair or fetal development, the osteoblasts deposit the collagen in a random weave arrangement. This type of bone is called woven bone. Woven bone is replaced by lamellar bone, which is formed much more slowly.

In lamellar bone, the collagen is arranged in parallel sheets. Lamellar bone can also form without a woven bone framework. There are two types of mature lamellar bone:

• Cortical (compact) bone – this is composed of numerous units called haversian systems. In each haversian system the lamellar bone is arranged concentrically around a central canal called the haversian canal, through which arteries and veins run.

• Cancellous (spongy) bone – this consists of lamellar bone arranged in a meshwork of bone trabeculae.

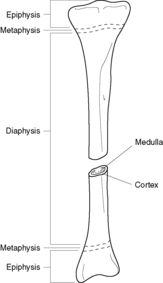

Most bones are tubular, hollow structures that consist of a shaft, called the diaphysis, expanded end regions, called the epiphyses, and a region between the diaphysis and each epiphysis, called the metaphysis (Figure 69). The sleeve-like tube (or cortex) of each bone is composed of compact sheets of cortical bone. The inner portion of bone is not quite hollow and is called the medulla. The medulla contains cancellous bone, connective tissue, nerves, blood vessels, fat, and haematopoietic tissue. All bones are covered by a periosteum composed of connective tissue.

|

| Figure 69 |

Development and growth of the skeleton

During fetal development, bone can be formed either directly in mesenchyme, as in the case of the skull and clavicles (intramembranous ossification), or on pre-existing cartilage (endochondral ossification). In intramembranous ossification, bone is laid down as woven bone that eventually matures into lamellar bone. In endochondral ossification, the cartilaginous template undergoes ossification at particular sites along the bone known as ossification centres. In long bones, the cartilage at the epiphysis persists until after puberty, allowing growth. This area of persisting cartilage is called the growth plate.

Once the bones are fully formed, further growth occurs by the laying down of further bone onto the pre-existing bone. The coordinated actions of the osteoblasts and osteoclasts are paramount in bone development and maintenance. In bone development, the action of osteoblasts predominates. When the skeleton has reached maturity, the bones are continually renewed and remodelled, which requires the actions of the osteoblasts and osteoclasts to be in equilibrium. By the third decade, osteoclastic resorption begins to predominate, with a resultant steady decrease in skeletal mass.

Developmental disorders

Achondroplasia

Achondroplasia is a major cause of dwarfism, and is due to mutation of a single gene. The condition can be familial, with autosomal dominant inheritance, or sporadic. The defective gene leads to abnormal ossification at the growth plates of bones formed by endochondral ossification. Intramembranous ossification is unaffected. Affected individuals have a characteristic appearance, with shortening of the proximal extremities, a relatively normal-sized trunk, and a disproportionately large head with typical bulging of the forehead and depression of the nasal bridge.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (‘brittle bone’ disease)

This is a rare group of genetic disorders that have in common the abnormal synthesis of type I collagen. In addition to bone, the other tissues rich in type I collagen are tendons, ligaments, skin, dentine and sclera. Affected individuals have brittle bones and spontaneous fractures may occur. The sclera appears blue because it is so thin that the underlying uveal pigment becomes visible. Some variants of osteogenesis imperfecta are fatal early in life while others are associated with survival.

Acquired disorders

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is characterised by reduced bone mass, making bone vulnerable to fracture. Trabecular bone is affected before cortical bone. Trabecular bone is found in the greatest amounts in the vertebral bodies and pelvis, and cortical bone is found in the greatest amounts in the long bones.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Osteoporosis may be primary or secondary. Primary osteoporosis refers to senile osteoporosis and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Secondary osteoporosis is due to conditions other than age or menopause, such as reduced mobility (e.g. after fracture or associated with rheumatoid arthritis), smoking and alcohol consumption, endocrine disorders (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism, diabetes) and corticosteroid therapy. Obesity and exercise appear to be protective against osteoporosis.

Senile osteoporosis There is a normal progressive loss of bone mass after around the age of 30years, and so all elderly people will have some degree of osteoporosis. Bone loss rarely exceeds 1% per year. The higher the initial bone density, the lower the risk of significant osteoporosis. Women are at higher risk than men, and white people are at higher risk than black people.

Post-menopausal osteoporosis Post-menopausal osteoporosis is characterised by hormone-dependent acceleration of bone loss. Post-menopausal women may lose up to 2% of cortical bone per year and up to 9% of trabecular bone per year for 8–10years, declining to the normal rate of bone loss after that. Oestrogen deficiency is thought to have a major role, and oestrogen replacement at the beginning of the menopause reduces the rate of bone loss.

Treatment

Women who take hormone replacement therapy have a reduced risk of developing post-menopausal osteoporosis. Also, oral bisphosphonates and vitamin D may be effective.

Metabolic bone disease

Rickets and osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is characterised by defective mineralisation of the osteoid matrix, and is associated with lack of vitamin D. When the condition occurs in the growing skeleton (children) it is called rickets. Vitamin D is important in the maintenance of adequate serum calcium and phosphorus levels, and deficiency impairs normal mineralisation of osteoid laid down in the remodelling of bone. The result is osteomalacia. In children, lack of vitamin D leads to inadequate mineralisation of the epiphyseal cartilage as well as the osteoid, resulting in rickets.

Aetiology

There are two main sources of vitamin D – dietary and endogenous. Consequently, there are four main causes of osteomalacia:

• Dietary deficiency of vitamin D – this used to be a common cause of rickets and osteomalacia. Improvements in diet and the addition of vitamin D to foodstuffs has drastically reduced the incidence of osteomalacia due to nutritional deficiency.

• Intestinal malabsorption – this is now the commonest cause of osteomalacia. Vitamin D is fat soluble. Any condition that causes malabsorption or poor absorption of fat (steatorrhoea) can cause osteomalacia. Causes include coeliac disease and Crohn’s disease.

• Deficiency of endogenous vitamin D due to defective synthesis in the skin – more than 90% of circulating vitamin D is photochemically synthesised in the skin. A steroid molecule precursor found in the epidermis is converted to vitamin D by UV light from the sun. Decreased exposure to sunlight or increased skin pigmentation hinders synthesis of vitamin D.

• Renal or liver disease – newly synthesised vitamin D is biologically inactive. A number of metabolic steps are required to convert vitamin D into its active form. The first of these steps is carried out by hepatocytes. The resulting compound is converted to the active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxycalciferol) in the kidney. Hence, renal disease and, to a lesser extent, liver disease can lead to a deficiency in the active form of vitamin D.

Clinicopathological features

The basic abnormality is deficient mineralisation of the organic matrix of the skeleton. In children, the skeleton becomes deformed because there is reduced structural rigidity and inadequate ossification at the growth plates. In pre-ambulatory infants, there is flattening of the occipital bones, and in ambulatory children, bowing of the legs and lumbar lordosis are characteristic. A pigeon breast deformity may develop due to the forces incurred on the weakened bones of the chest during normal respiration. Excess osteoid may cause frontal bossing of the head. Inadequate calcification of the epiphyseal cartilage in long bones leads to cartilaginous overgrowth at the growth plates, resulting in localised enlargement, which is seen especially at the wrists, knees and ankles. Overgrowth of the cartilage at the costochondral junctions of the chest results in an appearance that is referred to as a ‘rachitic rosary’.

In adults, the osteoid that is laid down in the remodelling of bone is inadequately mineralised. The shape of the bone is usually not affected, but the bone becomes vulnerable to spontaneous fractures. Looser zones (pseudofractures) are the hallmark of osteomalacia, and they appear on X-rays as transverse linear lucencies perpendicular to the bone surface. Persistent inadequate mineralisation may eventually lead to generalised osteopenia.

Hyperparathyroidism and renal osteodystrophy

These are discussed in Chapter 19.

Paget’s disease (osteitis deformans)

The aetiology of Paget’s disease is uncertain. There is an initial phase of osteoclastic resorption of bone followed by a ‘reparative phase’ in which there is intense osteoblastic activity and overproduction of disordered and architecturally abnormal bone. Bones may become larger than normal, and are composed of structurally unsound cortical bone and thickened trabeculae with numerous prominent cement lines, which give the bone its characteristic ‘mosaic pattern’ on microscopy. Later, bone may become ivory hard (‘sclerosis’). The abnormal bone is vulnerable to fracture.

Clinical features and complications

The clinical features and complications of Paget’s disease are:

• bone pain

• fractures

• neuropathies

• deformities

• deafness

• high-output heart failure

• osteosarcoma and other bone tumours.

The spinal cord and nerve roots are also at risk of compression due to enlargement of the vertebral bodies. Distortion of the middle ear cavity and VIIIth nerve compression may lead to deafness. Other cranial nerves may be affected by compression. The bones in Paget’s disease are extremely vascular, and the subsequent increased blood flow can (rarely) lead to high-output heart failure. Paget’s disease may be complicated by the development of bone tumours, the most sinister being osteosarcoma.

Diagnosis and treatment

Paget’s disease may be detected incidentally on X-ray or become manifest through the development of typical clinical features. Intense osteoblastic activity means that affected individuals have raised serum alkaline phosphatase levels. Treatment is with calcitonin and bisphosphonates.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis refers to inflammation of the bone and marrow, and is usually the result of infection.

Aetiology

Organisms may gain access to the bone by bloodstream spread from a distant infected site, by contiguous spread from neighbouring tissues, or by direct access via a penetrating injury. Almost any organism can cause osteomyelitis, but those most frequently implicated are bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for many cases. Patients with sickle cell disease are predisposed to Salmonella osteomyelitis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is sometimes implicated.

Pathogenesis

The location of the lesions within a particular bone depends on the intraosseous vascular circulation, which varies with age. In infants less than a year old, the epiphysis is usually affected. In children the metaphysis is usually affected, and in adults the diaphysis is most commonly affected.

In acute osteomyelitis, once the infection has become localised in bone, an intense acute inflammatory process begins. The release of numerous mediators into the haversian canals leads to compression of the arteries and veins, resulting in localised bone death (osteonecrosis). The bacteria and inflammation spread via the haversian systems to reach the periosteum. Subperiosteal abscess formation and lifting of the periosteum further impairs the blood supply to the bone, resulting in further necrosis. The dead piece of bone is called the sequestrum. Rupture of the periosteum leads to formation of drainage sinuses, which drain pus onto the skin. If osteomyelitis becomes chronic, a rind of viable new bone is formed around the sequestrum and below the periosteum. This new bone is called an involucrum. An intraosseous abscess, called a Brodie abscess, may form.

Clinical features and treatment

Acute osteomyelitis presents with localised bone pain and soft tissue swelling. If there is systemic infection, patients may present with an acute systemic illness. Presentation may be extremely subtle in children and infants, who may present only with pyrexia (pyrexia of unknown origin, PUO). Characteristic X-ray changes consist of a lytic focus of bone surrounded by a zone of sclerosis. Treatment requires aggressive antibiotic therapy. Inadequate treatment of acute osteomyelitis may lead to chronic osteomyelitis, which is notoriously difficult to manage. Surgical removal of bony tissue may be required.

Avascular necrosis

This is necrosis of bone due to ischaemia. Ischaemia may result if the blood supply to a bone is interrupted, which may occur if there is a fracture particularly in areas where blood supply is suboptimal (e.g. the scaphoid and the femoral neck). Most other cases of avascular necrosis are either idiopathic or follow corticosteroid administration.

Bone tumours

Primary bone tumours are uncommon. They can generally be classified according to whether they are cartilage-forming or bone-forming.

Benign cartilage-forming tumours

Osteochondroma (exostosis)

Osteochondromas are cartilage-capped bony outgrowths, which most frequently occur near the metaphysis of long bones. Affected individuals are usually less than 20years of age. Exostoses are usually solitary. Malignant change is very rare.

Chondroma (enchondroma)

Chondromas are cartilaginous tumours that usually arise within the medullary cavity of the bones of the hands and feet. They occur most frequently in the third to fifth decades of life. The lesions can sometimes cause localised pain, swelling, tenderness or pathological fracture. X-rays show the characteristic ‘O-ring’ sign – oval-shaped radiolucent cartilage surrounded by a dense rim of bone. Most chondromas are solitary. Malignant change is extremely rare.

Other rare benign cartilage-forming tumours are chondroblastomas and chondromyxoid fibromas.

Benign bone-forming tumours

Osteoma

These are bosselated tumours of bone, which most frequently occur in the skull and facial bones. Symptoms depend on the site at which they occur, e.g. symptoms due to obstruction of paranasal sinuses, symptoms related to impingement on the brain.

Osteoid osteoma

These round tumours consist of a small central area (called the ‘nidus’) surrounded by dense sclerotic bone. Affected individuals are usually less than 25years old. The lesions are characteristically painful.

Malignant bone-forming tumours

Osteosarcomas

These are the commonest primary malignant tumour of bone, and they usually affect young adults. The metaphysis of long bones are the most frequently affected sites, particularly the distal femur. They present as painful enlarging masses. The tumours usually penetrate the bone cortex, causing elevation of the periosteum. This produces the characteristic triangular shadow (Codman triangle) seen on X-ray, formed by the bone cortex and the elevated ends of the periosteum. Patients with hereditary retinoblastoma are at significantly increased risk of developing osteosarcomas. Mutations in the p53 gene have also been implicated in some cases. A few cases are secondary to Paget’s disease or previous radiation. These aggressive tumours can metastasise widely, especially to the lungs, but due to advances in treatment, the 5-year survival has improved to around 50%.

Miscellaneous bone tumours

Ewing’s sarcoma

This tumour is composed of small, round, darkly staining cells, which are now believed to be neuroectodermal in origin. The tumour affects children and adolescents, the average age at presentation being 10–15years. The pelvis and the diaphysis of long bones are the most frequently affected sites. The tumour presents as a painful enlarging mass, and some patients may have systemic features such as a fever, raised white cell count, or raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Treatment with radiotherapy and chemotherapy has drastically improved survival rates.

Fibroblastic tumours

Although fibroblastic tumours such as malignant fibrous histiocytomas and fibrosarcomas more frequently arise within soft tissues, they can also occur in bones. A quarter of cases are secondary to pre-existing conditions such as Paget’s disease, radiation, or bone infarct. The prognosis for high-grade tumours is poor.

Secondary bone tumours

The commonest malignant tumours of bone are secondary deposits from other sites. Most skeletal secondary deposits originate from malignancies at the following sites:

• lung

• breast

• thyroid

• kidney

• prostate.

These deposits cause osteolytic lesions to the bone, with the exception of secondaries originating from prostate tumours, which cause osteosclerotic lesions.

25.2. Joints

Structure and function

Joints are of two types:

• Solid joints – these joints are fixed and rigid, and allow only minimal movement. Examples of solid joints include the skull sutures (where the skull bones are bridged by fibrous tissue) and the symphysis pubis (where the bones are joined by cartilage).

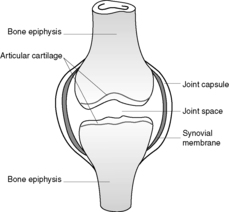

• Synovial joints – these joints have a joint space, which allows a wide range of movement. The articular cartilage in synovial joints is a specialised hyaline cartilage, which is an excellent shock absorber. The synovial membrane secretes synovial fluid into the joint space. Synovial fluid acts as a lubricant and provides nutrients for the articular hyaline cartilage (Figure 70).

|

| Figure 70 |

Osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease)

This is the most common type of joint disease, and is characterised by the progressive erosion of articular cartilage in weight-bearing joints. The incidence increases with age. Osteoarthritis can be primary or secondary to other bone or joint diseases, systemic diseases such as diabetes, a congenital or developmental deformity of a joint, or previous trauma including repetitive trauma.

Pathology and pathogenesis

Small fractures develop in the now articulating bone, allowing synovial fluid to enter the subchondral regions, with resultant formation of subchondral pseudocysts. Fragments of cartilage and bone fall into the joint space forming loose bodies (joint mice). Bony outgrowths, known as osteophytes, form at the margin of the articular cartilage. The articular surfaces become increasingly deformed.

The reason why the articular cartilage becomes predisposed to this damage appears to be related to biochemical alterations in the hyaline. In hyaline cartilage affected by osteoarthritis, the water content is increased and the proteoglycan content is decreased. The elasticity and compliance of the cartilage is, therefore, reduced. The very first change seen in osteoarthritis is proliferation of chondroblasts, and it has been proposed that these cells produce enzymes that induce these biochemical changes in the hyaline cartilage.

Clinical features

The most frequently affected joints are the hips, the knees, the cervical and lumbar vertebrae, the proximal and distal interphalangeal (PIP and DIP) joints of the hands, the first metacarpophalangeal joint and the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Osteophytes at the DIP joints produce nodular swellings called Heberden’s nodes. With increasing deformity of the joint the typical symptoms develop, which are pain (which is worse with use), morning stiffness, and limitation in joint movement. With involvement of the cervical and lumbar spine, osteophytes may impinge on the nerve roots causing symptoms such as pain and pins and needles in the arms or legs. The overall result is disability. The process cannot be halted.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disorder (hence rheumatoid ‘disease’), but the joints are invariably involved. The condition can affect all age groups. When children are affected, the condition is designated Still’s disease. Females are affected more often than males.

The pathogenesis is not well understood, but it is thought that an initiating agent, possibly an organism, triggers immunological dysfunction resulting in persistent chronic inflammation in genetically susceptible individuals. In the joints, the ongoing inflammation causes destruction of the articular cartilage. Circulating autoantibodies (rheumatoid factors), which are directed against autologous IgG immunoglobulins, can be detected in the serum of around 80% of affected individuals. The exact role of these autoantibodies is uncertain (see Box 9, Ch. 8).

Pathological features

Joints

The most severe morphological changes of rheumatoid arthritis are manifest in the joints. In the early stages the synovium becomes thickened, oedematous and hyperplastic. With ongoing inflammation, a pannus is formed. A pannus is a chronically inflamed fibrocellular mass of synovium and synovial stroma, which develops over the articular cartilage. As the pannus slowly spreads, it degrades the underlying cartilage, and erosions and subchondral cysts develop in the underlying bone. Small detached fragments fall into the joint space and are called rice bodies. Localised osteoporosis may also occur. The fibrous pannus eventually bridges the opposing bones causing limitation of movement, and ossification of this fibrous tissue leads to bony ankylosis. The inflammation also affects the joint capsule, tendons and ligaments causing characteristic deformities.

Skin

The most common cutaneous lesions are rheumatoid nodules, which arise in areas exposed to pressure, e.g. the extensor surfaces of the arms and the elbows. They are seen in ∼30% of patients. They arise in the subcutaneous tissue and manifest as firm, non-tender skin nodules. Microscopically, they consist of a central area of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by a palisade of histiocytes and fibroblasts.

Blood vessels

Patients with severe disease may develop a rheumatoid vasculitis. Peripheral neuropathy, skin ulceration, gangrene and nail-bed infarcts may develop. Impairment of blood supply to vital organs can be fatal.

Eyes

Scleritis and uveitis can develop.

Heart

The development of rheumatoid nodules in the conduction system may occur, and coronary artery vasculitis may result in myocardial ischaemia. Pericarditis can also be a feature.

Bones

Patients are at increased risk of localised and generalised osteoporosis.

Lymphoreticular

Patients may develop lymphadenopathy, with or without splenomegaly. The combination of rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly and neutropenia is called Felty’s syndrome. Approximately 50% of patients with Felty’s syndrome develop secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Patients may have a normocytic normochromic anaemia.

Miscellaneous

Patients are at an increased risk of developing amyloidosis.

Clinical features

The clinical course of rheumatoid arthritis is very variable. Some patients have mild disease, whereas others have severe progressive disease quickly leading to disability. Initially patients may suffer constitutional symptoms and only after a few weeks or months do the joints become involved. Generally, the small joints (especially those in the hands) are affected before the large joints. The affected joints are swollen, painful and stiff following a period of inactivity. Symptoms may improve with the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs or immunosuppressants. As a result of the pathological processes within the articular and periarticular tissues, characteristic deformities develop. These include:

• radial deviation at the wrists

• ulnar deviation at the fingers

• flexion and hyperextension deformities of the fingers (swan neck and boutonnière deformities).

Typical X-ray changes include:

• loss of articular cartilage leading to narrowing of the joint space

• joint effusions

• localised osteoporosis

• erosions.

Fatalities are usually the result of complications such as amyloidosis, vasculitis or the iatrogenic effects of therapy (e.g. gastrointestinal bleed secondary to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), infections secondary to steroids).

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies

The spondyloarthropathies are a group of disorders characterised by arthropathy associated with disease in other systems. Many are associated with human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 positivity. The term ‘seronegative’ is used because affected individuals are seronegative for rheumatoid factors.

Ankylosing spondylitis

This condition typically affects young men and ∼90% of patients are HLA-B27 positive. The changes are first seen in the sacroiliac joints and the spine. In the early stages there is inflammation of the tendo-ligamentous insertion sites, which is followed by reactive bone formation in the adjacent ligaments and tendons. This is compounded by a chronic synovitis causing destruction of the articular cartilage. With attempts at healing, the overall result is bony ankylosis and severe spinal immobility. Patients present with chronic progressive lower back pain. Further progression of the disease leads to spinal kyphosis and neck hyperextension (question mark posture). Characteristic X-ray changes include a ‘bamboo spine’ and squaring of the vertebral bodies. Extra-articular manifestations include:

• uveitis

• apical lung fibrosis

• aortic incompetence

• amyloidosis.

Reiter’s syndrome

This condition is defined as a triad of:

• arthritis

• urethritis (non-gonococcal)

• conjunctivitis.

Typical patients are young men, and ∼80% of patients are HLA-B27 positive. The condition usually follows infection of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract. Several weeks after the diarrhoea or urethritis, an arthritis develops, which may persist for many months. The joints of the leg are the most commonly affected sites.

Enteropathic arthropathy

Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia and Campylobacter gastroenteritis may be complicated by arthritis, with HLA-B27 positive individuals being at an increased risk of developing this complication. Arthritis is also seen in 20% of patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Psoriatic arthritis

An arthritis is developed by ∼5% of patients with psoriasis, and these individuals are usually HLA-B27 positive.

Infective arthritis

Organisms can gain access to the joint by three main routes:

• haematogenous spread from a distant infected site (most common)

• direct access via a penetrating injury

• direct spread from a neighbouring infected site, e.g. osteomyelitis, soft-tissue abscess.

Bacterial arthritis

Most cases of infective arthritis are caused by bacteria. The most common organisms are gonococcus (Neisseria), Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae and Gram-negative bacilli. In general, children are affected more commonly than adults. Gonococcal arthritis is seen mainly in late adolescence and adulthood, and patients with sickle-cell disease tend to develop Salmonella arthritis. Affected patients develop pain and swelling of the affected joint, and there may be systemic indicators of infection, e.g. fever. Aspiration and culture of the joint fluid gives the diagnosis. Prompt treatment with antibiotics is paramount.

Viral arthritis

Infections such as viral hepatitis, rubella and parvovirus B19 may be complicated by an arthritis. Symptoms are of a mild arthralgia (aching joints). It is not certain whether the virus directly infects the joint, or whether the arthritis is simply a reactive process due to systemic viral infection.

Rare forms of infective arthritis

Lyme disease

Lyme disease is caused by joint infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans via tick bites. Infection of the skin is followed by dissemination of the organism to many other sites, particularly the joints. The patient usually first develops a macular rash known as erythema migrans and there may be constitutional symptoms. This is followed by the development of an arthritis, which may affect more than one joint.

Tuberculous arthritis

Tuberculous arthritis is due to haematogenous spread from an established focus of infection elsewhere, usually the lungs. This condition usually presents with insidious development of joint pain associated with limitation of movement. The vertebral column is commonly involved, and when there is an associated osteomyelitis vertebral collapse may result (Pott’s disease of the spine).

Crystal arthropathies

Crystal arthropathies are a group of disorders caused by the deposition of crystals within the joint resulting in an acute and chronic arthritis. Such crystals may be endogenous or exogenous. The most common crystal arthropathies, gout and calcium pyrophosphate arthropathy, are due to endogenous crystal deposition.

Gout

Gout occurs due to the crystallisation of monosodium urate within a joint, resulting in an acute (gouty) arthritis, which is characterised by extreme localised pain, erythema, and exquisite tenderness of the affected joint. The most commonly affected joint is the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe, followed in decreasing frequency by the ankle, and then the knee. The disorder is due primarily to raised serum uric acid levels, but only around 3% of people with hyperuricaemia will develop gout. Uric acid is the end product of purine metabolism, and is excreted by the kidneys. Purines can either be derived from the breakdown of nucleic acids or synthesised de novo. Hyperuricaemia has several causes:

• idiopathic (80% of cases)

• overproduction of uric acid due to increased purine turnover (e.g. leukaemia) or an enzyme defect

• decreased excretion of uric acid (e.g. chronic renal failure, thiazide diuretics)

• high dietary purine intake.

The events which lead to the deposition of urate crystals in the joint are uncertain, but possible triggers include alcohol, trauma, surgery and infection. The presence of urate crystals within the joint causes the accumulation of numerous inflammatory cells. The resulting arthritis remits after a few days or weeks, even without treatment. The diagnosis can be confirmed by aspirating the joint fluid and using polarising microscopy to detect the needle-shaped crystals, which exhibit negative birefringence with a red filter.

Repeated attacks of acute gouty arthritis eventually lead to chronic tophaceous gouty arthritis, where the affected joint is damaged and function is impaired. Tophi are large aggregates of urate crystals, which are visible with the naked eye. They occur in the joints and soft tissues of people with persistent hyperuricaemia. A common site for tophi is the pinna of the ear.

Urate crystals can also become deposited in the kidney, resulting in acute uric acid nephropathy, chronic renal disease, or uric acid stones causing renal colic.

Calcium pyrophosphate arthropathy (pseudogout, chondrocalcinosis)

This condition is due to the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in the synovium (pseudogout) and articular cartilage (chondrocalcinosis). It can occur in three main settings:

• sporadic (more common in the elderly)

• hereditary

• secondary to other conditions, such as previous joint damage, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, haemochromatosis and diabetes.

The crystals first develop in the articular cartilage (chondrocalcinosis), which is usually asymptomatic. From here the crystals may shed into the joint cavity resulting in an acute arthritis, which mimics gout and is therefore called pseudogout. Pseudogout can be differentiated from gout in three ways:

• X-rays show the characteristic line of calcification of the articular cartilage

• the crystals look different under polarising microscopy – they are rhomboid in shape and exhibit positive birefringence with a red filter.

25.3. Connective tissue diseases

You should:

• understand the meaning of the term ‘connective tissue disease’

• know the various connective tissue diseases and their clinicopathological features

• understand what is known about the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma.

Basic principles

Connective tissue diseases is a convenient general term that covers a wide variety of disorders which have certain features in common:

• they are multisystem disorders and the joints, skin and subcutaneous tissue are often affected

• females are more commonly affected than males

• immunological abnormalities are often present

• a chronic clinical course is usual

• they usually respond to anti-inflammatory drugs.

The conditions included in this group of disorders are:

• rheumatoid arthritis (presented above)

• systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

• polyarteritis nodosa (PAN)

• dermatomyositis and polymyositis

• polymyalgia rheumatica

• cranial arteritis

• scleroderma (systemic sclerosis).

Systemic lupus erythematosus

SLE is a multisystem disorder of autoimmune origin. Females are affected more commonly than males (the female to male ratio is 9:1), and the disease usually arises in the second or third decade.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

The cause of SLE is unknown but most patients have circulating autoantibodies directed against nuclear antigens (antinuclear antibodies, or ANAs) and these autoantibodies are the mediators of the tissue damage. Hence B cell hyper-reactivity is implicated in the pathogenesis and evidence suggests that it is excess T cell help that drives self-reactive B cells to produce these autoantibodies. Genetic factors may also be important, since there is a strong familial tendency to develop SLE. Some cases of SLE are drug induced, hydralazine and procainamide being among the drugs implicated.

Clinicopathological features

Most visceral lesions are mediated by type III hypersensitivity (immune complex hypersensitivity reaction). The haematological effects are mediated by type II hypersensitivity. The organs and tissues affected and the various pathological manifestations are shown in Table 58.

| Organ affected | Clinicopathological features |

|---|---|

| Skin (involved in most patients) | Symmetrical erythematous facial ‘butterfly’ rash, often precipitated by sun exposure |

| Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) | |

| Joints | Arthralgia |

| Kidneys | Glomerulonephritis, which may progress to renal failure |

| Central nervous system | Psychiatric symptoms |

| Focal neurological symptoms due to non-inflammatory occlusion of small blood vessels | |

| Cardiovascular system | Pericarditis |

| Myocarditis | |

| Libman–Sacks endocarditis (rare) | |

| Necrotising vasculitis | |

| Lungs | Pleuritis |

| Pleural effusions | |

| Lymphoreticular | Mild lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly |

| Haematological | Anaemia |

| Leucopenia | |

| Thrombophilia (antiphospholipid antibody syndrome) |

The typical presentation of SLE is of a young woman with a butterfly rash on her face associated with a fever and arthralgia. Alternatively, fever or arthralgia may be the only symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Some patients who have autoantibodies directed against cardiolipin develop the anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, characterised by thrombophilia. Affected women may have recurrent miscarriages.

The clinical course of the condition is variable. That most frequently seen is a relapsing remitting course spanning years. Exacerbations are treated with steroids or other immunosuppressants. Death is usually due to renal disease, diffuse central nervous system (CNS) disease or intercurrent infection.

Polyarteritis nodosa

PAN is characterised by inflammation and fibrinoid necrosis of small or medium-sized arteries. The aetiology is unknown. Segmental artery wall damage may lead to aneurysm formation. The primary targets of PAN are the main visceral vessels, with the kidneys being affected most frequently, followed by the heart, liver and gastrointestinal tract. Joints, muscles, nerves, the skin and the lungs may also be involved.

Clinical features

The diagnosis depends on finding a necrotising vasculitis in a biopsy specimen. The serum of affected patients often contains pANCA (perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody).

Therapy with corticosteroids or cyclophosphamide causes remission in most cases. If left untreated, PAN is often fatal.

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis

Both of these conditions are inflammatory disorders of muscle, and they present with gradual onset of muscular weakness. More than one muscle is usually affected and the distribution is commonly bilateral, symmetrical and proximal. The oesophagus, diaphragm and heart are not infrequently involved. In dermatomyositis, a distinctive skin rash precedes the muscular weakness. The rash is a lilac discoloration of the upper eyelids associated with periorbital oedema. A more generalised dermatitis is often present. Ten per cent of patients with dermatomyositis have an underlying malignancy, most commonly carcinoma of the lung, breast or gastrointestinal tract. Polymyositis differs from dermatomyositis because it lacks the skin changes and is seen only in adults. There is a slight increased risk of an underlying malignancy.

Diagnosis of these disorders depends on clinical symptoms, elevated muscle enzymes (e.g. creatinine phosphokinase) and muscle biopsy.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

This condition is seen in elderly individuals, and presents with pain and stiffness in the shoulder and pelvic girdles. Muscle weakness is not a feature. There may be non-specific features such as lethargy, raised ESR and mild normochromic normocytic anaemia. The condition responds well to corticosteroid therapy.

Cranial arteritis (temporal or giant cell arteritis)

Cranial arteritis is a granulomatous inflammation of small and medium-sized arteries, and is the commonest of the vasculitides. The inflammatory process principally affects the cranial vessels, especially the temporal arteries and the terminal branches of the ophthalmic artery. In such cases, prompt diagnosis is paramount because of the risk of blindness. Typical symptoms are headache, scalp tenderness in the region of the temporal artery, and jaw claudication. The condition may also be associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. A raised serum ESR should raise the possibility of cranial arteritis.

Diagnosis depends on temporal artery biopsy, which should be performed immediately if the diagnosis is suspected. Histologically, the wall of the artery is infiltrated by inflammatory cells, with or without multinucleate giant cells, and the internal elastic lamina becomes fragmented. These changes may only be focal (‘skip’ lesions) and may be missed on biopsy. The treatment of choice is steroids.

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis)

This condition is characterised by excessive fibrosis of organs and tissues. The skin is almost always affected with variable involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, heart, kidneys, lungs, arteries, and musculoskeletal system. The condition is more common in women than men. In a subset of patients where the skin is the main target organ and visceral involvement is uncommon, the condition is often associated with CREST syndrome. CREST is an acronym for:

• Calcinosis

• Raynaud syndrome

• oEsophageal dysfunction

• Sclerodactyly

• Telangiectasia.

Aetiology

The principal underlying abnormality is excessive production and deposition of collagen. The mechanism by which this occurs is uncertain, but disordered immune activation appears to be involved with excess T cell help driving the production of fibrogenic mediators by inflammatory cells.

Clinicopathological features

Most patients present with Raynaud phenomenon and the characteristic skin changes, but some patients also develop symptoms related to involvement of other organs.

Skin

Becomes tight and tethered and joint mobility becomes impaired. The hands and fingers are usually affected first, the fingers become tapered and the hand takes on a claw-like configuration. Involvement of the face causes taut facial skin and the mouth appears small. At a microscopic level, there is skin oedema followed by progressive fibrosis of the dermis and epidermal atrophy. Impaired blood supply due to arterial involvement may lead to skin ulceration and autoamputation of digits.

Gastrointestinal tract

There is fibrous replacement of the muscularis. This change can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, but the oesophagus is frequently involved resulting in dysphagia. When other parts of the gastrointestinal tract are affected, malabsorption may result.

Kidneys

The renal abnormalities are due to changes in the vasculature. Vascular lesions are confined to the medium-sized arteries and are similar to those seen in hypertension. Ten to thirty per cent of patients with scleroderma develop hypertension, and in a proportion of these cases there is malignant hypertension, which may prove fatal.

Heart

Pericarditis with effusions and myocardial fibrosis are seen rarely.

Musculoskeletal

There may be polyarthritis and myositis.

Progression of the disease is usually slow, unless superseded by malignant hypertension. Death may occur from:

• renal failure secondary to malignant hypertension

• severe respiratory compromise

• cor pulmonale

• cardiac failure or arrhythmias secondary to myocardial fibrosis.

25.4. Soft tissue tumours

Soft tissue can be defined as non-epithelial, extraskeletal tissue of the body, exclusive of the reticuloendothelial system, glia, meninges, and the visceral parenchyma. Soft tissue tumours are a highly heterogeneous and complex group of neoplasms, which are classified according to the mature tissues that they most closely resemble. For example, lipomas and liposarcomas resemble to a varying degree normal fatty tissue. Benign soft tissue tumours (particularly lipomas) are extremely common among the general population, and many never need medial attention. Malignant soft tissue tumours (sarcomas) on the other hand are relatively rare, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers. However, sarcomas often behave extremely aggressively and are capable of metastasising widely. This, together with the fact that most sarcomas tend to arise within deep soft tissues and have often grown to a large size before they become clinically apparent, means that the prognosis is generally quite poor.

Because of the complex nature of this group of tumours, we present only a framework for the basic understanding of the various types of soft tissue tumours that exist (see Table 59). For the purposes of this book, it is not necessary to detail each specific entity, but some of the more common soft tissue tumours (e.g. leiomyoma of the uterus) are presented in other chapters.

| Mature tissue resembled | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Fat | Lipoma | Liposarcoma |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

| Skeletal muscle | Rhabdomyoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Blood vessels | Haemangioma | Angiosarcoma |

| Perivascular tissue | Glomus tumour | Malignant glomus tumour |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibroma | Fibrosarcoma |

| Fibrohistiocytic tumours | Fibrous histiocytoma | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma |

| Nerves | Schwannoma, neurofibroma | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour |

Self-assessment: questions

One best answer questions

2. A 68-year-old man presents with an acutely painful, red and tender ankle. He takes diuretics for cardiac disease and regularly drinks red wine with his evening meal. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. tuberculous arthritis

b. osteomyelitis

c. Paget’s disease

d. gout

e. osteosarcoma

True-false questions

1. The following statements are correct:

a. osteogenesis imperfecta is caused by dietary insufficiency

b. osteoporosis rarely occurs in men

c. osteomalacia and rickets are caused by a lack of vitamin K

d. bowing of the legs is a feature of osteomalacia

e. in Paget’s disease, affected bones become enlarged and are therefore not vulnerable to fracture

2. The following statements are correct:

a. Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for the majority of cases of pyogenic osteomyelitis

b. osteomyelitis may complicate compound fractures

c. following its fracture, the scaphoid bone is particularly vulnerable to avascular necrosis

d. osteosarcomas are the most common bone tumours

e. bone tumours may form cartilage

3. Osteoarthritis:

a. is caused by bacterial infection of the articular cartilage

b. is a multisystem disorder

c. is characterised by pannus formation

d. usually affects the weight-bearing joints

e. is associated with Heberden’s nodes, which represent prominent osteophytes at the distal interphalangeal joints

4. The following statements are correct:

a. rheumatoid arthritis is a multisystem disorder

b. rheumatoid factor is an autoantibody that is directed against articular cartilage

c. in rheumatoid arthritis, joint deformities may develop in the hands

d. the majority of patients with ankylosing spondylitis are HLA-B27 positive

e. in ankylosing spondylitis, the most frequently affected joints are those of the lower limbs

5. The following statements are correct:

a. bacterial infective arthritis may cause joint destruction

b. gout is due to deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals within the joint

c. the joint most frequently affected by gout is the knee joint

d. use of diuretics may predispose to the development of gout

e. the crystal seen in joints affected by pseudogout are rhomboid in shape and exhibit positive birefringence on polarising microscopy

6. Systemic lupus erythematosus:

a. is more common in females than males

b. in most cases is characterised by circulating antinuclear antibodies, which mediate the tissue damage

c. may be drug-induced

d. causes renal abnormalities in almost all patients

e. may be associated with a skin rash that is limited to the trunk

7. The following statements are correct:

a. patients with dermatomyositis have an increased risk of developing visceral malignancies

b. cANCA is often detected in the serum of patients with polyarteritis nodosa

c. cranial (temporal) arteritis may lead to blindness if untreated

d. systemic sclerosis is characterised by excess deposition of collagen

e. skin involvement, which is characteristic of systemic sclerosis, is not seen in patients with CREST syndrome

8. The following statements are true:

a. ankylosing spondylitis is the commonest joint disease

b. seronegative spondyloarthropathies are associated with seronegativity for HLA-B27

c. arthritis occurs in the majority of patients with psoriasis

e. tophi are skin lesions characteristically seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

9. The following are features of rheumatoid arthritis:

a. radial deviation at the wrist joint and ulnar deviation at the finger joint in patients with joint deformities

b. widening of the joint space on X-ray

c. lymphadenopathy

d. vasculitis

e. heart disease

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 60-year-old woman attends the accident and emergency department complaining of pain in her left hip following a trivial fall. A history reveals that she has been getting backache for some time. She is otherwise well but has been on steroids for Crohn’s disease for some time. An X-ray demonstrates a fractured femoral neck.

1. What underlying diagnoses would you consider?

2. How would this patient be managed?

Case history 2

A 71-year-old man with a 20-year history of rheumatoid disease regularly attends an outpatient rheumatology clinic for investigation, physiotherapy and adjustment of his drug treatment. He is presently on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclophosphamide. At his last clinic appointment he complained of increasing shortness of breath on exertion. Auscultation of the chest revealed late inspiratory crepitations. A chest X-ray shows a finely reticulated appearance. Serum haematology showed a normocytic normochromic anaemia.

1. What deformities might you expect to see in the hands of this patient?

2. What might be the cause of his increasing shortness of breath?

3. What are the possible causes of his anaemia?

Short note questions

Write short notes on:

1. The aetiology of osteomalacia.

2. The pathogenesis of osteomyelitis.

3. CREST syndrome.

4. Autoantibodies.

Viva questions

1. What functions does bone perform?

2. How are bone tumours classified?

3. What features do the seronegative spondyloarthropathies have in common as a group of disorders?

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

2. d. The ankle signs suggest an acute arthritis; the diuretic use and alcohol consumption are factors associated with hyperuricaemia and triggering of monosodium urate crystal deposition with joints. The ankle is a common site for gout. Tuberculous arthritis typically presents with gradual development of joint pain and limitation of movement in a patient with established infection elsewhere in the body. Osteomyelitis presents with localised bone pain and soft tissue swelling; in adults it most commonly involves the diaphysis rather than joints. Osteosarcoma also presents with bone pain and soft tissue swelling; symptoms are usually present for several months before diagnosis. Paget’s disease may be asymptomatic, or present with symptoms including bone pain, heart failure, pathological fracture and nerve compression.

True-false answers

1.

a. False.

b. False. Osteoporosis occurs in both males and females.

c. False.

d. False. In osteomalacia the shape of the bone is not affected.

e. False. Affected bones are more vulnerable to fracture because the enlarged bone is structurally unsound.

2.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True.

d. False. Metastases are the most common tumours of bone. Osteosarcomas are the most common primary bone cancers.

e. True.

3.

a. False.

b. False.

c. False. Pannus formation is seen in rheumatoid arthritis.

d. True.

e. True.

4.

a. True.

b. False.

c. True.

d. True.

e. False.

5.

a. True.

b. False.

c. False.

d. True.

e. True.

6.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True.

d. True.

e. False. The skin rash is not limited to the trunk.

7.

a. True.

b. False. pANCA (not cANCA) is often detected in PAN.

c. True.

d. True.

e. False.

8.

a. False. Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease.

b. False. The term ‘seronegative’ in this context denotes seronegativity for rheumatoid factor.

c. False. Psoriatic arthropathy occurs in a minority of patients, around 5%.

d. False.

e. False. Tophi are characteristically seen in gout. The skin lesions seen in rheumatoid arthritis are called rheumatoid nodules.

9.

a. True.

b. False. The joint space is typically narrowed.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True. The heart may be involved by pericarditis, vasculitis, rheumatoid nodules or amyloidosis.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. In this situation, a number of underlying pathologies should be considered. Most cases of fractured neck of femur are due to underlying osteoporosis. The recent history of backache and the fact that this woman is taking steroids would support this diagnosis. The other main diagnosis to consider is a pathological fracture secondary to bony metastases. The recent history of backache may be due to the presence of metastatic deposits in the spine. It is also important to realise that bones affected by Paget’s disease and osteomalacia are prone to fracture. The appearance of the bone adjacent to the fracture on X-ray may help establish the diagnosis.

Case history 2

1. This man has had rheumatoid arthritis for some time now and so many deformities may be present in the hands including swelling of the interphalangeal joints, flexion and hyperextension deformities of the fingers, radial deviation at the wrists and ulnar deviation at the metacarpophalangeal joints. In elderly individuals, you may also see changes related to osteoarthritis.

2. Increasing shortness of breath associated with coarse crackles on auscultation of the lung fields and a ground-glass appearance on chest X-ray would raise the suspicion of interstitial lung disease, which patients with rheumatoid arthritis are at increased risk of developing. Lung function tests could be performed to confirm this.

3. A normocytic normochromic anaemia is seen in anaemia of chronic disease, which is the most likely cause of the anaemia in this case. However, in the presence of anaemia in a patient on long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment, the possibility of chronic blood loss owing to drug-induced peptic ulceration should be considered, but this would characteristically induce a microcytic anaemia.

Short note answers

1. Osteomalacia is caused by vitamin D deficiency. To give a full account of the aetiology, you must understand how vitamin D deficiency may arise. There are two main sources of vitamin D – diet and endogenous synthesis in the skin. Hence, poor diet, intestinal malabsorption and reduced exposure to sunlight may all lead to osteomalacia. Newly synthesised vitamin D is biologically inactive and conversion to its active form occurs in the liver and kidneys. Hence renal disease and liver disease may also lead to osteomalacia.

2. Remember that the term ‘pathogenesis’ refers to the process of production and development of a lesion, i.e. the mechanism through which the aetiology operates to produce the pathological and clinical manifestation. Hence, a sequence of events linking the aetiological agent to the end lesion is what is wanted here. The aetiological agent in osteomyelitis is a microorganism, which may gain access to bone via several routes. When the infection has been localised in bone, the ensuing inflammation causes a sequence of events culminating in bone necrosis.

3. CREST syndrome is associated with systemic sclerosis. There are two main forms of systemic sclerosis: diffuse and localised. The diffuse form is characterised by widespread skin involvement and early visceral involvement. The localised form is characterised by usually localised skin involvement and late visceral involvement. Calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, oesophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly and telangiectasia are features often seen in the localised form, and affected patients are then sometimes said to have CREST syndrome (CREST being an acronym of these five features).

4. Comment: Start by giving a definition of what an autoantibody is: an antibody directed against self-antigens (or autoantigens). Interactions between autoantibodies and autoantigens evoke an immune response against the individual’s own tissues, a process known as autoimmunity. The immune reaction is self-perpetuating, causing chronic inflammatory disorders, which are known as autoimmune diseases. At this point, it would be a good idea to list the main autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and rheumatoid arthritis, remembering also to include some ‘organ-specific’ autoimmune diseases such as Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and myasthenia gravis.

Viva answers

1. Bone performs a number of functions other than just providing structural support. It is protective to certain organs, and it is involved in mineral homeostasis and haematopoiesis.

2. Comment: You should devise a system that enables you to classify all tumours. A simple one is to divide them into primary tumours and secondary tumours. Primary tumours are then subdivided into benign and malignant. Further classification is usually according to the cell of origin or histological appearance, and for bone tumours this means dividing them into those that are bone-forming, those that are cartilage-forming, and miscellaneous tumours such as Ewing’s sarcoma and fibroblastic tumours.

3. The seronegative spondyloarthropathies are a group of disorders characterised by an inflammatory arthritis associated with disorders (usually infectious) in other systems. They include ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, enteropathic arthropathy and psoriatic arthritis. Patients are seronegative for rheumatoid factors, and many are HLA-B27 positive.