Bone Marrow Examination

After completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Diagram bone marrow architecture and locate hematopoietic tissue.

2. List indications for bone marrow examinations.

3. Specify sites for bone marrow aspirate and biopsy.

4. Assemble supplies for performing and assisting in bone marrow specimen collection.

5. Assist the physician with bone marrow sample preparation subsequent to collection.

6. List the information gained from bone marrow aspirates and biopsy specimens.

7. Perform a bone marrow aspirate smear and core biopsy specimen examination.

8. List the normal hematopoietic and stromal cells of the bone marrow and their anticipated distribution.

9. Perform a bone marrow differential count and compute the myeloid-to-erythroid ratio.

10. Characterize features of hematopoietic and metastatic tumor cells.

11. Prepare specimens for and assist in performing specialized confirmatory bone marrow studies.

12. Prepare a systematic written bone marrow examination report.

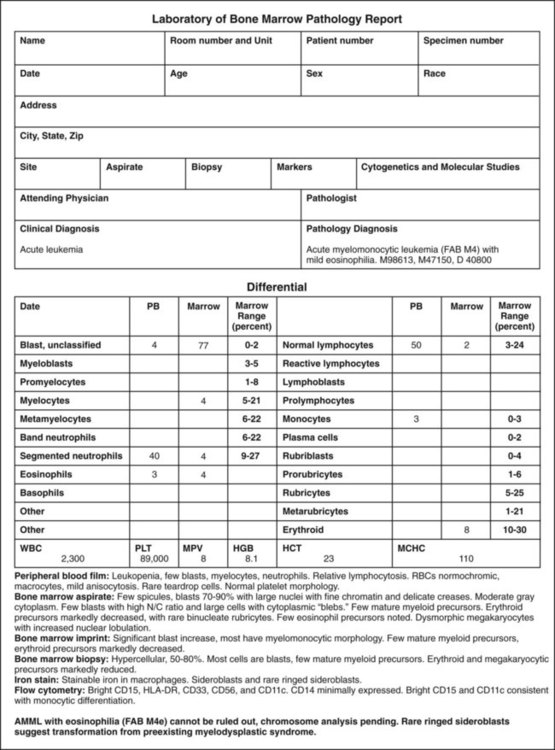

Case Study

1. What bone marrow finding provides information on blood cell production?

2. What is the myeloid-to-erythroid ratio in this patient, and what does it indicate?

3. What megakaryocyte distribution is normally seen in a bone marrow aspirate?

Bone Marrow Anatomy and Architecture

In adults, bone marrow accounts for 3.4% to 5.9% of body weight, contributes 1600 to 3700 g or a volume of 30 to 50 mL/kg, and produces roughly six billion blood cells per kilogram per day in a process called hematopoiesis.1 At birth, nearly all the bones contain red hematopoietic marrow (see Chapter 7). In the fifth to seventh year, adipocytes (fat cells) begin to replace red marrow in the long bones of the hands, feet, legs, and arms, producing yellow marrow, and by late adolescence hematopoietic marrow is limited to the lower skull, vertebrae, shoulder, pelvic girdle, ribs, and sternum (see Figure 7-2). Although the percentage of bony space devoted to hematopoiesis is considerably reduced, the overall volume remains constant as the individual matures.2 Yellow marrow reverts to hematopoiesis, increasing red marrow volume, in conditions such as chronic blood loss or hemolytic anemia that raise demand.

The arrangement of red marrow and its relationship to the central venous sinus is illustrated in Figure 7-3. Hematopoietic tissue is enmeshed in spongy trabeculae (bony tissue) surrounding a network of sinuses that originate at the endosteum (vascular layer just within the bone) and terminate in collecting venules.3 Adipocytes occupy approximately 50% of red hematopoietic marrow space in a 30- to 70-year-old adult, and fatty metamorphosis increases approximately 10% per decade after 70.4

Indications for Bone Marrow Examination

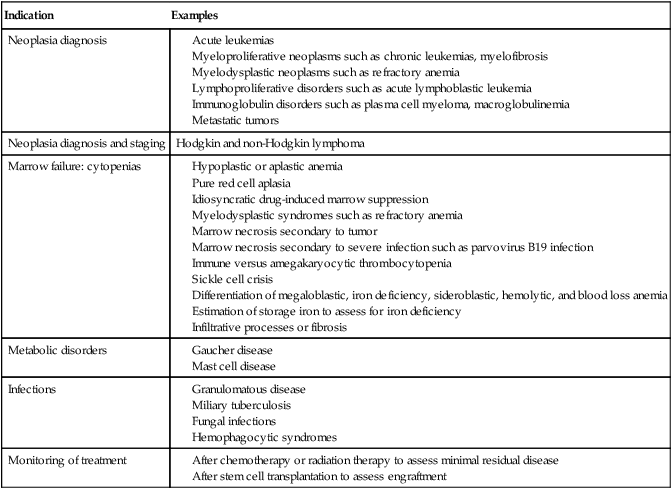

Table 16-1 summarizes indications for examination of bone marrow.5 Bone marrow examinations may be used to diagnose and stage hematologic and nonhematologic neoplasia, to determine the cause of cytopenias, and to confirm or exclude metabolic and infectious conditions suspected on the basis of clinical symptoms and peripheral blood findings.6

Hypoplastic or aplastic anemia

Idiosyncratic drug-induced marrow suppression

Myelodysplastic syndromes such as refractory anemia

Marrow necrosis secondary to tumor

Marrow necrosis secondary to severe infection such as parvovirus B19 infection

Immune versus amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia

Differentiation of megaloblastic, iron deficiency, sideroblastic, hemolytic, and blood loss anemia

Bone Marrow Specimen Collection Sites

Bone marrow specimen collection is a collaboration between a medical laboratory scientist (medical technologist) and a skilled specialty physician, often a pathologist or hematologist.7 Prior to bone marrow collection, the medical laboratory scientist collects peripheral blood for a complete blood count with blood film examination. During collection, the scientist assists the physician by managing the specimens and producing initial preparations for examination.

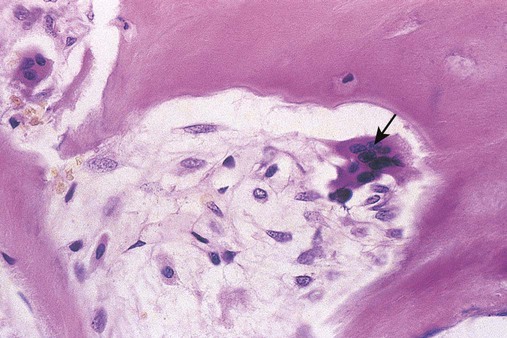

The core biopsy specimen is particularly important for evaluating diseases that characteristically produce focal lesions, rather than diffuse involvement of the marrow. Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, metastatic tumors, amyloid, and granulomas produce predominantly focal lesions. Granulomas, or granulomatous lesions, are cell accumulations that contain Langerhans cells—large, activated granular macrophages that look like epithelial cells. Granulomas signal chronic infection. The biopsy specimen also allows morphologic evaluation of bony spicules, which may reveal changes associated with hyperparathyroidism or Paget disease.8

Bone marrow collection sites include the following:

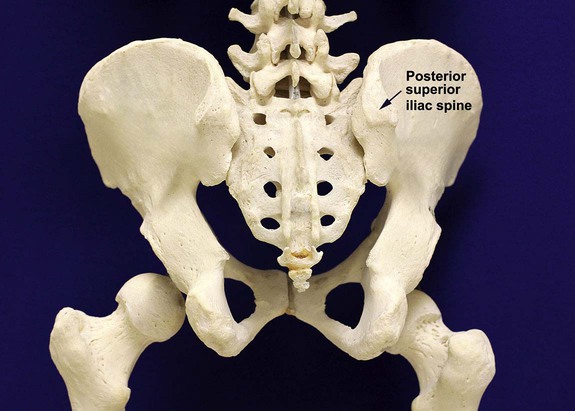

• Posterior superior iliac crest (spine) of the pelvis (Figure 16-1). In both adults and children, this site provides adequate red marrow that is isolated from anatomic structures which are subject to injury. This site is used for both aspiration and core biopsy.

• Anterior superior iliac crest (spine) of the pelvis. This site has the same advantages as the posterior superior iliac crest, but the cortical bone is thicker. This site may be preferred for a patient who can only lie supine.

• Sternum, below the angle of Lewis at the second intercostal space. In adults, the sternum provides ample material for aspiration but is only 1 cm thick and cannot be used for core biopsy. It is possible for the physician to accidentally transfix the sternum and enter the pericardium within, damaging the heart or great vessels.

• Anterior medial surface of the tibia in children younger than age 2. This site may be used only for aspiration.

• Spinous process of the vertebrae, ribs, or other red marrow–containing bones. These locations are available but are rarely used unless they are the site of a suspicious lesion discovered on a radiograph.

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy

Preparation

• Antiseptic solution and alcohol pads.

• Local anesthetic injection, usually 1% lidocaine, not to exceed 20 mL per patient.

• No. 11 scalpel blade for skin incision.

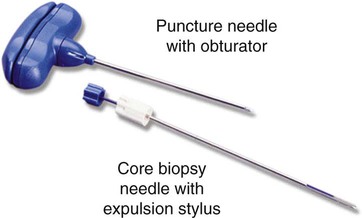

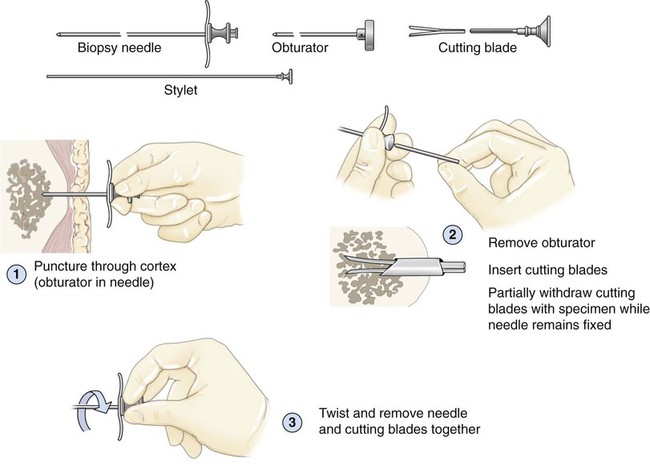

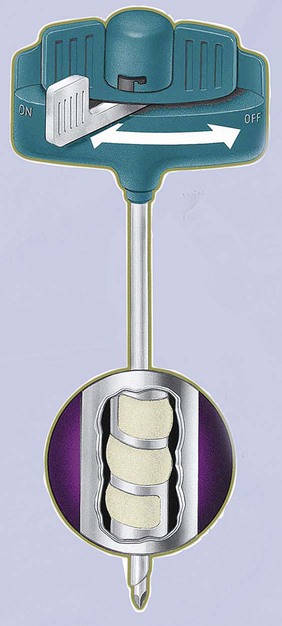

• Disposable Jamshidi biopsy needle (Care Fusion; Figure 16-2) or Westerman-Jensen needle (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, N.J.; Figure 16-3). Both provide an obturator, core biopsy tool, and stylet. A Snarecoil biopsy needle also is available (Kendall Company, Mansfield, Mass.). The Snarecoil has a coil mechanism at the needle tip that allows for capture of the bone marrow specimen without needle redirection (Figure 16-4).

• Disposable 14- to 18-gauge aspiration needle with obturator. Alternatively, the University of Illinois aspiration needle may be used for sternal puncture. The University of Illinois needle provides a flange that prevents penetration of the sternum to the pericardium.

• Microscope slides or coverslips washed in 70% ethanol.

• Petri dishes or shallow circular watch glasses.

• Vials or test tubes with closures.

• Anticoagulant liquid tripotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K3EDTA).

• Zenker fixative: potassium dichromate, mercuric chloride, sodium sulfate, and glacial acetic acid; B5 fixative: aqueous mercuric chloride and sodium acetate, or 10% neutral formalin. Because Zenker fixative and B5 contain toxic mercury, controlled disposal is required.

Bone Marrow Sample Management

Direct Aspirate Smears

Crush Smears

The crush preparation procedure may also be performed using ethanol-washed coverslips in place of slides. The coverslip method demands adroit manipulation but may yield better morphologic information, because the smaller coverslips generate less cell rupture during separation. Use of glass slides offers the opportunity for automated staining, whereas coverslip preparations must first be affixed smear side up to slides and then stained manually (see Chapter 15).

Marrow Smear Dyes

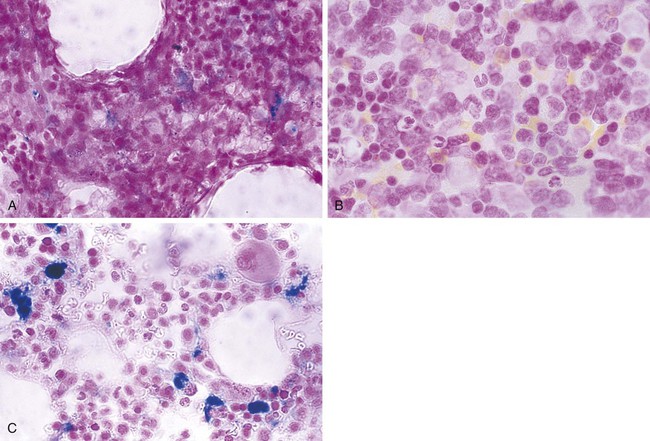

Marrow aspirate smears and core biopsy specimens may also be stained using a ferric ferricyanide (Prussian blue) solution to detect and estimate marrow storage iron or iron metabolism abnormalities (see Chapter 19). Further, a number of cytochemical dyes are used for cell identification or differentiation (Table 16-2 and Chapter 30).

TABLE 16-2

Cytochemical Dyes Used to Identify Bone Marrow Cells and Maturation Stages

| Cytochemical Dye | Application |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Detects myelocytic cells by staining cytoplasmic granular contents |

| Sudan black B (SBB) | Detects myelocytic cells by staining cytoplasmic granular contents |

| Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) | Detects lymphocytic cells and certain abnormal erythrocytic cells by staining of cytoplasmic glycogen |

| Esterases | Distinguish myelocytic from monocytic maturation stages (several esterase substrates) |

| Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) | Detects tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase granules in hairy cell leukemia |

Bone Marrow Aspirate or Imprint Examination

Box 16-1 describes the uses of low- and high-power objectives in examining bone marrow aspirate direct smears or imprints.

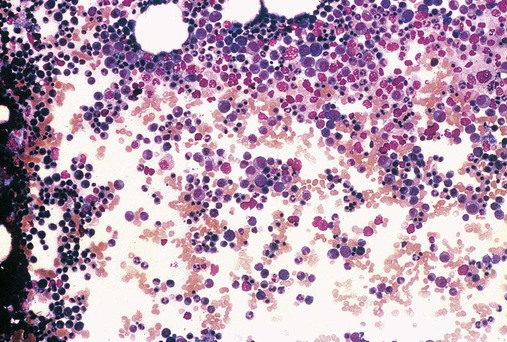

Low-Power (100×) Examination

Once the bone marrow aspirate direct smear or imprint is prepared and stained, the scientist or pathologist begins the microscopic examination using the low-power (10×) dry lens, which, when coupled with 10× oculars, provides a total 100× magnification. Most bone marrow examinations are performed using a teaching report format that employs projection or multiheaded microscopes to allow viewing by residents, fellows, medical laboratory science students, and attending staff. The microscopist locates the bony spicules, aggregations of bone and hematopoietic marrow, which stain dark blue (Figure 16-5). In imprints, spicules are sparse or absent, and the search is for hematopoietic cells instead. Within these areas, intact and nearly contiguous nucleated cells are selected for examination, whereas areas showing distorted morphology or dilution with sinusoidal blood are avoided.

Near the spicules, cellularity is estimated by observing the proportion of hematopoietic cells to adipocytes (clear fat areas).9 For iliac crest marrow, 50% cellularity is normal for patients aged 30 to 70 years. In childhood, cellularity is 80%, and after age 70, cellularity is reduced. For those older than age 70, a rule of thumb is to subtract patient age from 100% and add ±10%. Thus for a 75-year-old, the anticipated cellularity is 15% to 35%. By comparing with the age-related normal cellularity values, the microscopist classifies the observed area as hypocellular, normocellular, or hypercellular. If a core biopsy specimen was collected it provides a more accurate estimate of cellularity than an aspirate smear, because in aspirates there is always some dilution of hematopoietic tissue with sinus blood. In the absence of leukemia, lymphocytes should total fewer than 30% of nucleated cells; if more are present, the marrow specimen has been substantially diluted and should not be used to estimate cellularity.10

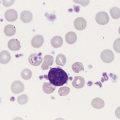

The microscopist evaluates megakaryocytes using low power (Figure 16-6). Megakaryocytes are the largest cells in the bone marrow, 30 to 50 µm in diameter, with multilobed nuclei (see Chapter 13). Although in special circumstances microscopists may differentiate three megakaryocyte maturation stages—megakaryoblast, promegakaryocyte, and megakaryocyte (MK-I to MK-III)—a total megakaryocyte estimate is generally satisfactory. In a well-prepared aspirate or biopsy specimen, the microscopist observes 2 to 10 megakaryocytes per low-power field. Deviations yield important information reported as decreased or increased megakaryocytes. Bone marrow megakaryocyte estimates are essential to the evaluation of peripheral blood thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis; for instance, in immune thrombocytopenia, marrow megakaryocytes proliferate markedly.

High-Power (500×) Examination

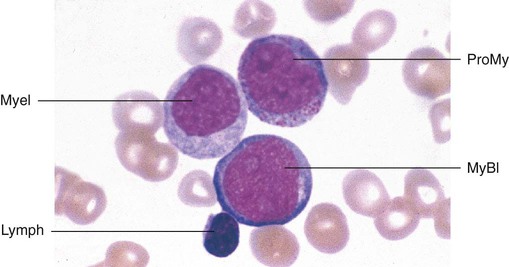

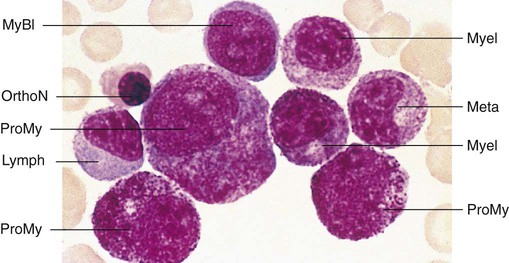

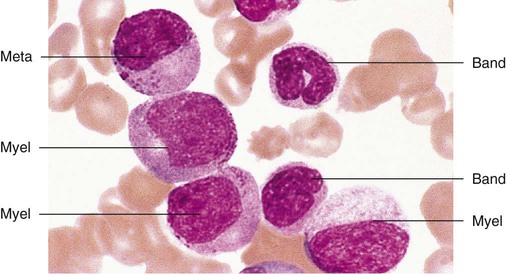

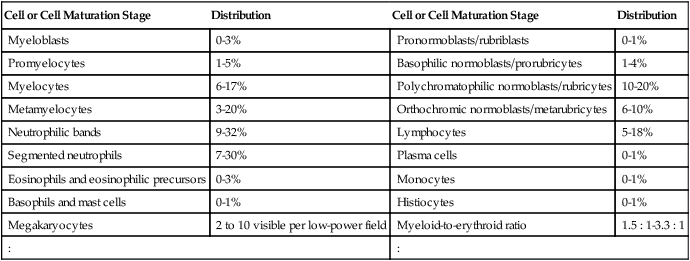

Having located a suitable examination area, the microscopist places a drop of immersion oil on the specimen and switches to the 50× objective, providing 500× total magnification. All of the nucleated cells are reviewed for morphology and normal maturation. Besides megakaryocytes, cells of the myelocytic (Figures 16-7 through 16-10) and erythrocytic (rubricytic, normoblastic, Figure 16-11) series should be present, along with eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, and histiocytes. See Chapters 7, 8, and 12 for detailed cell and stage descriptions. Table 16-3 names all normal marrow cells and provides their expected percentages.

TABLE 16-3

Anticipated Distribution of Cells and Cell Maturation Stages in Aspirates or Imprints

| Cell or Cell Maturation Stage | Distribution | Cell or Cell Maturation Stage | Distribution |

| Myeloblasts | 0-3% | Pronormoblasts/rubriblasts | 0-1% |

| Promyelocytes | 1-5% | Basophilic normoblasts/prorubricytes | 1-4% |

| Myelocytes | 6-17% | Polychromatophilic normoblasts/rubricytes | 10-20% |

| Metamyelocytes | 3-20% | Orthochromic normoblasts/metarubricytes | 6-10% |

| Neutrophilic bands | 9-32% | Lymphocytes | 5-18% |

| Segmented neutrophils | 7-30% | Plasma cells | 0-1% |

| Eosinophils and eosinophilic precursors | 0-3% | Monocytes | 0-1% |

| Basophils and mast cells | 0-1% | Histiocytes | 0-1% |

| Megakaryocytes | 2 to 10 visible per low-power field | Myeloid-to-erythroid ratio | 1.5 : 1-3.3 : 1 |

| : | : | ||

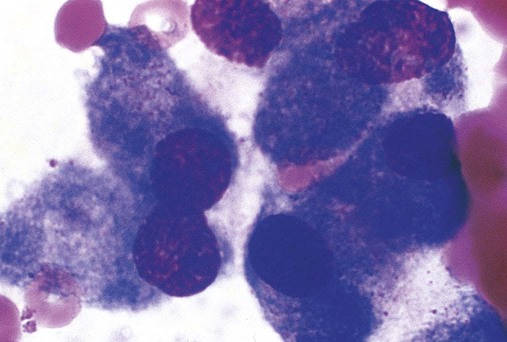

The microscopist may infrequently find osteoblasts and osteoclasts (Figure 16-12). Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation and remodeling, and derive from endosteal (inner lining) cells. Osteoblasts resemble plasma cells with eccentric round to oval nuclei and abundant blue, mottled cytoplasm, but lack the prominent Golgi apparatus characteristic of plasma cells. Osteoblasts are usually found in clusters resembling myeloma cell clusters. Their presence in marrow aspirates and core biopsy specimens is incidental; they do not signal disease, but they may create confusion.

Osteoclasts are nearly the diameter of megakaryocytes, but their multiple, evenly spaced nuclei distinguish them from multilobed megakaryocyte nuclei (Figure 16-13). Osteoclasts appear to derive from myeloid progenitor cells and are responsible for bone resorption, acting in concert with osteoblasts. Osteoclasts are recognized more often in core biopsy specimens than in aspirates.

Adipocytes, endothelial cells that line blood vessels, and fibroblast-like reticular cells complete the bone marrow stroma (see Chapter 7). Stromal cells and their extracellular matrix provide the suitable microenvironment for the maturation and proliferation of hematopoietic cells, but are seldom examined for diagnosis of hematologic or systemic disease.

Prussian Blue Iron Stain Examination

A Prussian blue (ferric ferricyanide) iron stain is commonly used on the aspirate smear. Figure 16-14 illustrates normal iron, absence of iron, and increased iron stores in aspirate smears. The iron stain may be used for core biopsy specimens, but decalcifying agents used to soften the biopsy specimen during processing may leech iron, which gives a false impression of decreased or absent iron stores. For this reason, the aspirate is favored for the iron stain if sufficient spicules are present.

Bone Marrow Core Biopsy Specimen Examination

The standard dye for the core biopsy specimen is H&E. Other dyes and their purposes are listed in Table 16-4.

TABLE 16-4

Dyes Used in Examination of Bone Marrow Core Biopsy Specimens

| Dye | Comment |

| Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) | Used to evaluate cellularity and hematopoietic cell distribution, locate abnormal cell clusters. |

| Prussian blue (ferric ferricyanide) iron stain | Used to evaluate iron stores for deficiency or excess iron. Decalcification may remove iron from fixed specimens; thus ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid chelation or the aspirate smear is preferred for iron store estimation. |

| Reticulin and trichrome dyes | Used to examine for marrow fibrosis. |

| Acid-fast stains | Used to examine for acid-fast bacilli, fungi, or bacteria in granulomatous disease. |

| Gram stain | Used to examine for acid-fast bacilli, fungi, or bacteria in granulomatous disease. |

| Immunohistochemical dyes | Dye-tagged monoclonal antibodies specific for tumor surface markers are used to establish the identity of malignant cells. |

| Wright or Wright-Giemsa dyes | Used to observe hematopoietic cell structure. Cell identification is less accurate in a biopsy specimen than in an aspirate smear. |

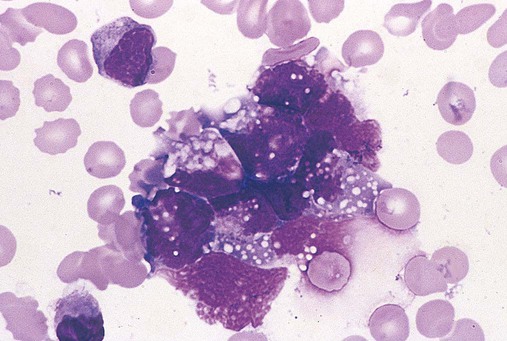

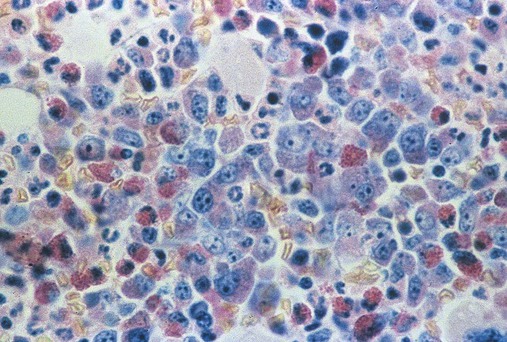

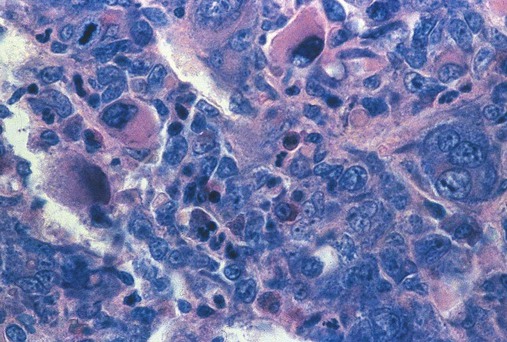

Bone marrow core biopsy specimen and imprint (touch preparation) examinations are essential when the aspiration procedure yields a dry tap, which may be the result of hypoplastic or aplastic anemia, fibrosis, or tight packing of the marrow cavity with leukemic cells. The key advantage of the core biopsy specimen is preservation of bone marrow architecture so that cells, tumor clusters (Figure 16-15), and maturation stages may be examined relative to stromal elements. The disadvantage is that individual hematopoietic cell morphology is obscured.

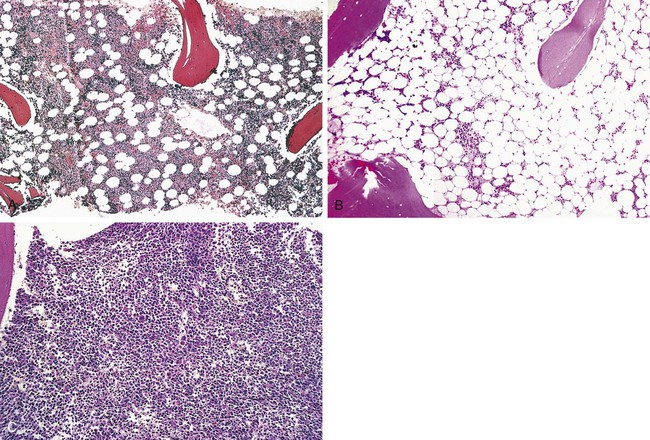

The microscopist first examines the core biopsy specimen preparation using the 10× objective (100× total magnification) to assess cellularity. Because the sample is larger, the core biopsy specimen provides a more accurate estimate of cellularity than the aspirate. The estimate is made by comparing cellular areas with the clear-appearing adipocytes, using a method identical to that employed in examination of aspirate smears. All fields are examined, because cells distribute unevenly. Examples of hypocellular and hypercellular core biopsy sections are provided for comparison with normocellular marrow in Figure 16-16.

Megakaryocytes are easily recognized by their outsized diameter and even distribution throughout the biopsy. They exhibit the characteristic lobulated nucleus, although nuclei of the more mature megakaryocytes are smaller and more darkly stained in H&E preparations than on a Wright-stained aspirate. Their cytoplasm varies from light pink in younger cells to dark pink in older cells (Figure 16-17). Owing to the greater sample volume, megakaryocyte numbers are assessed more accurately by examining a core biopsy section than an aspirate smear. Normally there are 2 to 10 megakaryocytes per 10× field, the same as in an aspirate smear or imprint.

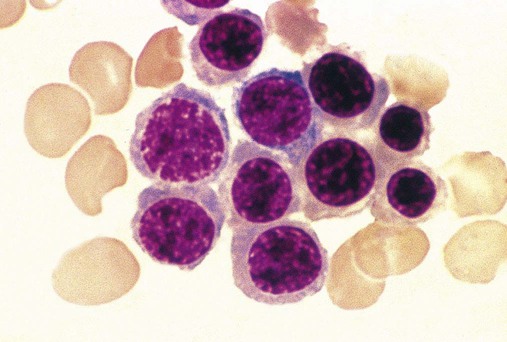

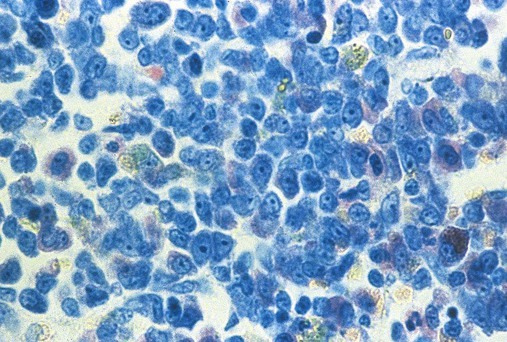

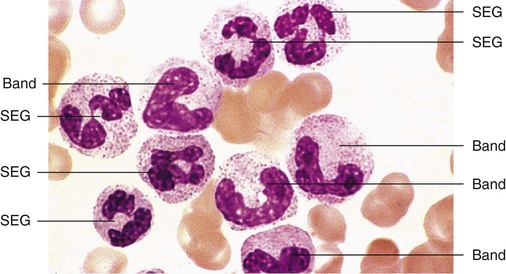

If no aspirate or imprint smears could be prepared, the core biopsy specimen may be stained using Wright, Giemsa, or Wright-Giemsa dyes to make limited observations of cellular morphology. In Wright- or Giemsa-stained biopsy sections, myeloblasts and promyelocytes have oval or round nuclei with cytoplasm that stains blue (Figure 16-18). Neutrophilic myelocytes and metamyelocytes have light pink cytoplasm. Mature segmented neutrophils (SEGs) and neutrophilic bands are recognized by their smaller diameter and darkly stained C-shaped nuclei (bands) or nuclear segments (SEGs). The cytoplasm of bands and SEGs may be light pink or may seem unstained (Figure 16-19).

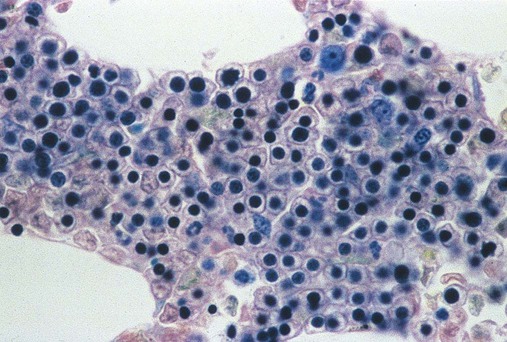

The microscopist may find it difficult to differentiate myelocytic cells from erythrocytic cells in biopsy specimens other than to observe that the latter tend to cluster with more mature normoblasts and often surround histiocytes. Polychromatophilic and orthochromic normoblasts, the two most common erythrocytic maturation stages, have centrally placed, round nuclei that stain intensely (Figure 16-20). Their cytoplasm is not appreciably stained, but the plasma membrane margin is clearly discerned, which gives the cells of these stages a “fried egg” appearance. Because erythrocytic cells have a tendency to cluster in small groups, they are more easily recognized using the 10× objective, although their individual morphology cannot be seen.

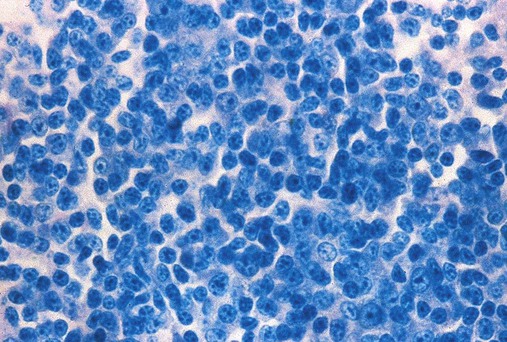

Lymphocytes are among the most difficult cells to recognize in the core biopsy specimen, unless they occur in clusters. Mature lymphocytes exhibit speckled nuclear chromatin in a small, round nucleus, along with a scant amount of blue cytoplasm (Figure 16-21). Immature lymphocytes (prolymphocytes) have larger round or lobulated nuclei but still only a small rim of blue cytoplasm.

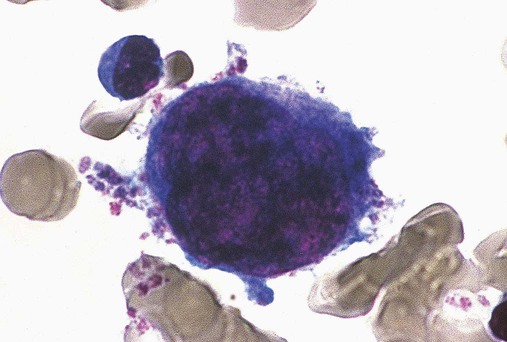

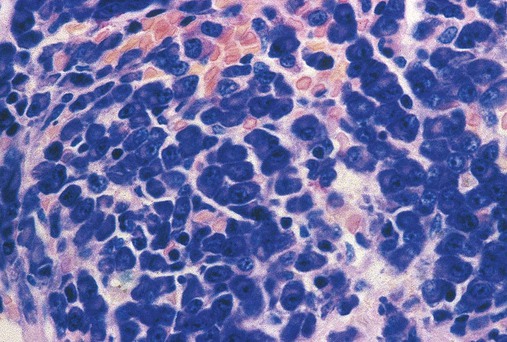

Plasma cells are difficult to distinguish from myelocytes in H&E-stained sections but are recognized using Wright-Giemsa dye as cells with eccentric dark nuclei and blue cytoplasm and a prominent pale central Golgi apparatus (Figure 16-22). Characteristically, plasma cells are located adjacent to blood vessels.

Definitive Bone Marrow Studies

Although in many cases the aspirate smear and biopsy specimen are diagnostic, additional studies may be needed. Such studies and their applications are given in Table 16-5. These studies require additional bone marrow volume and specialized specimen collection. Information on Prussian blue iron stains and cytochemistry was provided earlier. Each study is described in the chapter referenced in the Table 16-5.

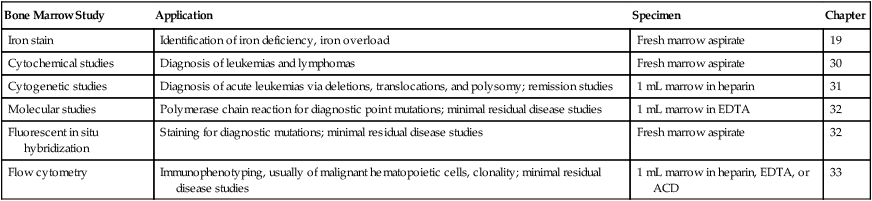

TABLE 16-5

Definitive Studies Performed on Selected Bone Marrow Specimens

| Bone Marrow Study | Application | Specimen | Chapter |

| Iron stain | Identification of iron deficiency, iron overload | Fresh marrow aspirate | 19 |

| Cytochemical studies | Diagnosis of leukemias and lymphomas | Fresh marrow aspirate | 30 |

| Cytogenetic studies | Diagnosis of acute leukemias via deletions, translocations, and polysomy; remission studies | 1 mL marrow in heparin | 31 |

| Molecular studies | Polymerase chain reaction for diagnostic point mutations; minimal residual disease studies | 1 mL marrow in EDTA | 32 |

| Fluorescent in situ hybridization | Staining for diagnostic mutations; minimal residual disease studies | Fresh marrow aspirate | 32 |

| Flow cytometry | Immunophenotyping, usually of malignant hematopoietic cells, clonality; minimal residual disease studies | 1 mL marrow in heparin, EDTA, or ACD | 33 |

ACD, Acid-citrate dextrose; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

Bone Marrow Examination Reports

The components of a bone marrow report should be generated systematically and are given in Table 16-6. An example of a bone marrow examination report is provided in Figure 16-23.

TABLE 16-6

Components of a Bone Marrow Examination Report

| Component | Description |

| Patient history | Patient identity and age, narration of symptoms, physical findings, findings in kindred, treatment |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Peripheral blood CBC collected no more than 24 hours before the bone marrow puncture, includes hemogram and peripheral blood film examination |

| Cellularity | Hypocellular, normocellular, or hypercellular classification based on ratio of hematopoietic cells to adipocytes |

| Megakaryocytes | Estimate at 10× magnification compared with reference interval and comment on morphology |

| Maturation | Narrative characterizing the maturation of the myelocytic and erythrocytic (normoblastic, rubricytic) series |

| Additional hematologic cells | Narrative describing numbers and morphology of eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, and histiocytes if appropriate, with reference intervals |

| Stromal cells | Narrative describing numbers and morphology of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, bony trabeculae, fibroblasts, adipocytes, and endothelial cells; appearance of sinuses; presence of amyloid, granulomas, fibrosis, necrosis |

| Differential count | Numbers of all cells and cell stages observed after performing a differential count on 300 to 1000 cells and comparing results with reference intervals |

| Myeloid-to-erythroid ratio | Computed from nucleated hematologic cells less lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, and histiocytes |

| Iron stores | Categorization of findings as increased, normal, or decreased iron stores |

| Diagnostic narrative | Summary of the recorded findings and additional laboratory chemical, microbiologic, and immunoassay tests |

Summary

• Adult hematopoietic tissue is located in the flat bones and the ends of the long bones. Hematopoiesis occurs within the spongy trabeculae of the bone adjacent to vascular sinuses.

• Bone marrow collection is a safe but invasive procedure performed by a pathologist or hematologist in collaboration with a medical laboratory scientist to obtain specimens for diagnosis of hematologic and systemic disease and monitoring of treatment.

• The necessity for a bone marrow examination should be evaluated in light of all clinical and laboratory information. In anemias for which the cause is apparent from the RBC indices, a bone marrow examination is not required. Examples of indications for bone marrow examination include multilineage abnormalities in the peripheral blood, pancytopenia, circulating blasts, and staging of lymphomas and carcinomas.

• A peripheral blood specimen is collected for a complete blood count no more than 24 hours before the bone marrow is collected and the results of the tests are reported together.

• Bone marrow may be collected from the posterior or anterior iliac crest or sternum using sterile disposable biopsy and aspiration needles and cannulas. The site and equipment depend on how old the patient is and whether both an aspirate and a biopsy specimen are desired.

• The medical laboratory scientist receives the bone marrow specimen and prepares aspirate smears, crush preparations, imprints, anticoagulated bone marrow smears, and fixed biopsy sections, and specimens for confirmatory studies.

• The medical laboratory scientist and pathologist collaborate with residents, fellows, attending physicians, and medical laboratory science students to stain and review bone marrow aspirate smears, biopsy sections, and confirmatory procedure results.

• Confirmatory procedures include cytochemistry, cytogenetics, and immunophenotyping by flow cytometry; fluorescence in situ hybridization; and molecular diagnostics.

• The medical laboratory scientist and pathologist determine cellularity and megakaryocyte distribution, then perform a differential count of 300 to 1000 bone marrow hematopoietic cells and compute the M : E ratio, comparing the results with reference intervals.

• The pathologist characterizes features of hematopoietic disease, metastatic tumor cells, and abnormalities of the bone marrow stroma and prepares a systematic written bone marrow examination report including a diagnostic narrative.

Review Questions

1. Where is most hematopoietic tissue found in adults?

2. What is the preferred bone marrow collection site in adults?

a. Second intercostal space on the sternum

b. Anterior or posterior iliac crest

3. The aspirate should be examined under low power to assess all of the following except:

4. What is the normal M : E ratio range in adults?

5. What is the most common erythrocytic stage found in normal marrow?

6. What cells, occasionally seen in bone marrow biopsy specimens, are responsible for the formation of bone?

7. What is the largest hematopoietic cell found in a normal bone marrow aspirate?

8. Which of the following is not an indication for a bone marrow examination?

a. Pancytopenia (reduced numbers of RBCs, WBCs, and platelets in the peripheral blood)

b. Anemia with RBC indices corresponding to low serum iron and low ferritin levels

9. In a bone marrow biopsy specimen, the RBC precursors were estimated to account for 40% of the cells in the marrow, and the other 60% were granulocyte precursors. What is the M : E ratio?

10. On a bone marrow core biopsy sample, several large cells with multiple nuclei were noted. They were located close to the endosteum, and their nuclei were evenly spaced throughout the cell. What are these cells?

11. The advantage of a core biopsy bone marrow sample over an aspirate is that the core biopsy specimen:

to

to  the length of the slide, similar to a peripheral blood film. Bony spicules 0.5 to 1.0 mm in diameter and larger fat globules follow behind the spreader and deposit on the slide. In the direct smear preparation, the spicules are not squashed. The smears may be fanned to promote rapid drying in an effort to preserve cell morphology.

the length of the slide, similar to a peripheral blood film. Bony spicules 0.5 to 1.0 mm in diameter and larger fat globules follow behind the spreader and deposit on the slide. In the direct smear preparation, the spicules are not squashed. The smears may be fanned to promote rapid drying in an effort to preserve cell morphology.