Blood Trematodes

1. List the clinically significant blood trematodes.

2. Describe the general life cycle of the blood trematodes and how human infection occurs.

3. Explain the diagnostic methods used to identify blood trematodes.

4. Differentiate the eggs of the five species of schistosomes.

5. Describe the pathogenesis of the blood trematodes.

6. List the drugs of choice for treatment of blood trematode infections.

7. Describe where blood trematodes are found and how infection may be prevented.

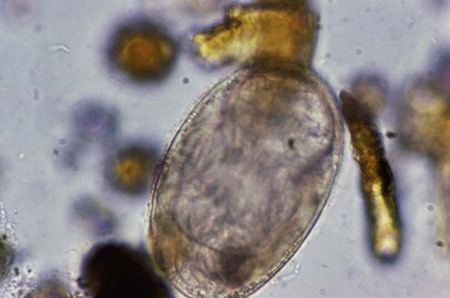

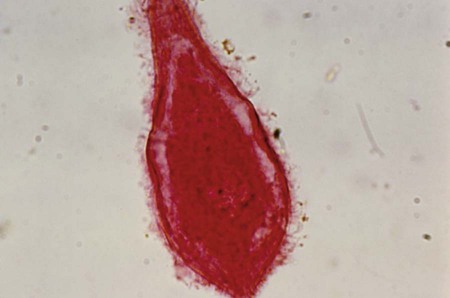

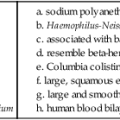

General Characteristics

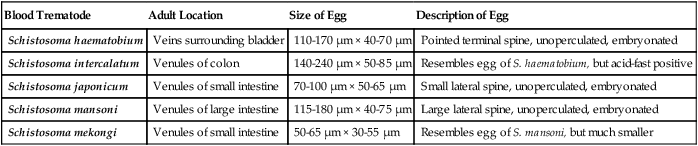

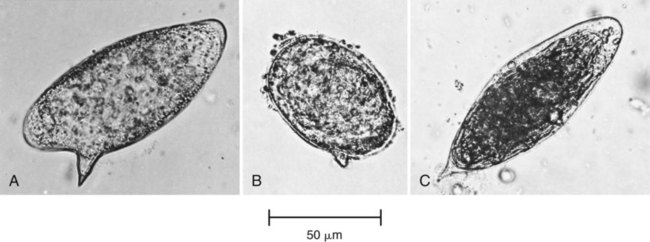

Unlike the other trematodes, adult schistosomes are not flattened, but are rather long, thin, and rounded in shape. There is an oral sucker surrounding the mouth and a ventral sucker located just slightly below the oral sucker. The adult male averages 1.5 cm in length and is wider than the female, having a ventral fold that wraps around the female when they mate (Figure 58-1). The adult female averages 2 cm in length and is very thin. The eggs of each species are distinct, and can be distinguished by size, spine morphology, and sometimes specimen type (Figure 58-2). The size range for eggs of S. haematobium is 110 to 170 µm long by 40 to 70 µm wide, and they have a sharply pointed terminal spine. They are fully embryonated without an operculum. The size range for the eggs of S. japonicum is 70 to 100 µm long by 50 to 65 µm wide, and they have a small lateral spine that is sometimes difficult to detect (Figure 58-3). S. mekongi eggs are smaller than those of S. japonicum, ranging in size from 50 to 65 µm long by 30 to 55 µm wide. They are fully embryonated without an operculum and have a small lateral spine. The size range for eggs of S. mansoni is 115 to 180 µm long by 40 to 75 µm wide, and they have a large lateral spine. S. mansoni eggs are unoperculate, immature when released, and take up to 8 to 10 days to develop a miracidium. S. intercalatum eggs are fully embryonated without an operculum, have a terminal spine, and range in size from 140 to 240 µm long by 50 to 85 µm wide. S. intercalatum eggs resemble those of S. haematobium and can be differentiated by Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast positivity. In addition, S. intercalatum eggs are only found in feces, not in urine specimens. Table 58-1 provides a comparison of the schistosome eggs.

TABLE 58-1

Diagnostic Characteristics of the Blood Trematodes

| Blood Trematode | Adult Location | Size of Egg | Description of Egg |

| Schistosoma haematobium | Veins surrounding bladder | 110-170 µm × 40-70 µm | Pointed terminal spine, unoperculated, embryonated |

| Schistosoma intercalatum | Venules of colon | 140-240 µm × 50-85 µm | Resembles egg of S. haematobium, but acid-fast positive |

| Schistosoma japonicum | Venules of small intestine | 70-100 µm × 50-65 µm | Small lateral spine, unoperculated, embryonated |

| Schistosoma mansoni | Venules of large intestine | 115-180 µm × 40-75 µm | Large lateral spine, unoperculated, embryonated |

| Schistosoma mekongi | Venules of small intestine | 50-65 µm × 30-55 µm | Resembles egg of S. mansoni, but much smaller |

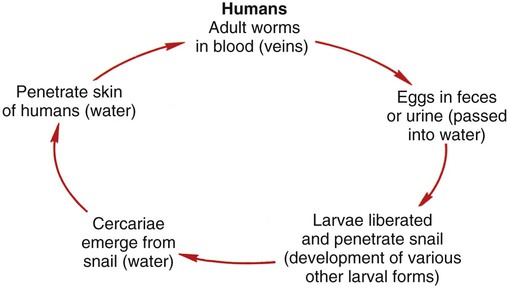

One of the main differences in the schistosomes from other trematodes is that instead of being hermaphroditic, there are separate male and female adult worms. In human infection, the adult worms live in either the veins that supply the intestine (S. japonicum and S. mansoni) or the veins that supply the urinary bladder (S. haematobium). The eggs are passed from the body in either the feces or the urine. To reach the inside of the intestine or bladder, the eggs must penetrate the tissue from the veins. This is accomplished via a spine that is distinctive among the major species. The embryonated egg will release the miracidium (Figure 58-4) once it reaches freshwater, and will enter the snail host, where it will develop into the infectious cercaria. The free-swimming cercariae are capable of penetrating through the human skin directly and do not encyst on aquatic vegetation or other aquatic wildlife (Figure 58-5). The cercariae penetrate the host tissue until they reach a vein; then they travel to capillaries near the lungs and then to the portal vein of the liver, where they mature. When they are mature, the adult males will pair with the females and then travel to the veins of either the intestine or the bladder, where the eggs are produced (Figure 58-6).

Laboratory Diagnosis

The standard method of diagnosis is by the detection of characteristic eggs in feces or rectal biopsy, for S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. mansoni, and S. intercalatum (and perhaps S. haematobium if these worms have migrated to a bladder vein that is close to the intestine); and in urine (usually concentrated before examination) or bladder tissue biopsy for S. haematobium. A wet mount with/without iodine from a sedimentation or concentration method can be examined for eggs. Figure 58-2 provides images of three different schistosome eggs. To optimize recovery of S. haematobium in urine, the specimen should be collected between noon and 2 pm.