Blood and Tissue (Filarial) Nematodes

1. Describe the distinguishing morphologic characteristics and basic life cycle (vectors, hosts, and stages of infectivity) for each of the parasites listed.

2. Define microfilariae, hydrocele, chyluria, and sheath.

3. Describe the diseases and mechanism of pathogenicity, including route of transmission for each of the species listed.

4. Explain periodicity, including nocturnal and diurnal, as it relates to infection with microfilariae and correlate with the life cycle of the associated arthropod vector.

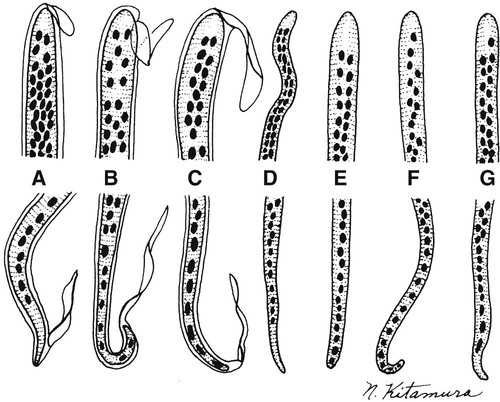

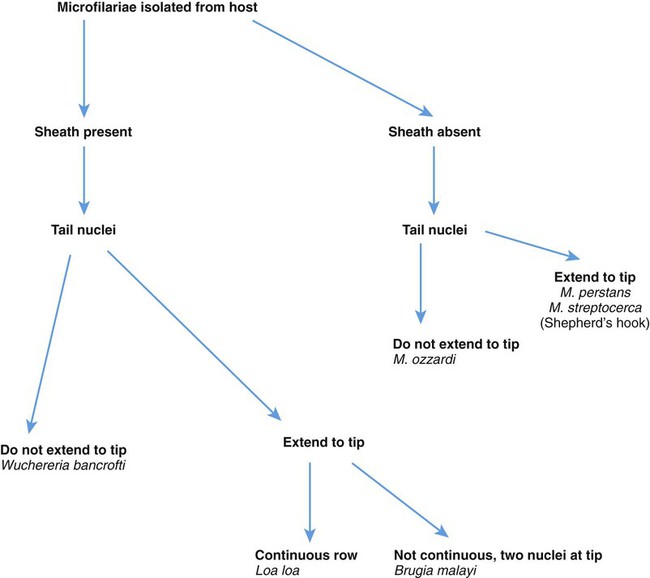

5. Differentiate the microfilariae based on the presence or absence of the sheath and the arrangement and number of tail nuclei.

6. Describe the two methods for concentration of blood specimens for the identification of organisms within the peripheral blood.

7. Determine the etiology of infection based on patient history, signs and symptoms, and laboratory results.

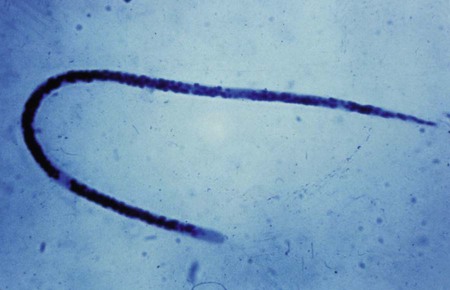

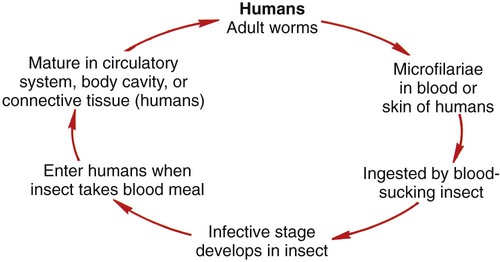

Blood and tissue filarial nematodes are roundworms that infect humans. These organisms are transmitted via a blood-sucking arthropod vector such as a mosquito, midge, or fly. The filarial nematodes infect the subcutaneous tissues, deep connective tissues, body cavities, and lymphatic system. The life cycles of the filarial nematodes are complex (Figure 53-1). The infective larval stage resides in the insect vector with the adult worm stage, which is the pathogenic form in humans. When the arthropod vector feeds on a human blood meal, the infective larvae are injected into the bloodstream. The larvae are motile and migrate to the lymphatic vessels. The infective larvae grow and develop into the adult gravid worm in the human host over a period of months. The male and female adult worms mate in the definitive human host. The female worm produces large numbers of larvae called microfilariae. Depending on the species, the microfilariae may maintain the egg membrane as a sheath or may rupture the egg membrane, resulting in an unsheathed form. These parasites can reside in the host for many years and cause chronic, debilitating conditions and severe inflammatory responses. Identification of the various species is based on the morphology of the microfilaria, the periodicity (defined circadian rhythm), and the location within the human host. Microfilariae morphologic characteristics are important in the identification and include the presence or absence of the sheath and the presence and arrangement of the nuclei in the tail of the worm (Figure 53-2). A comparison of the morphologic characteristics of the pathogenic filarial worms is depicted in Figure 53-3. Diagnosis of infection is based on the identification of the microfilariae in the blood or tissue of the host.

Wuchereria Bancrofti

General Characteristics

Wuchereria bancrofti is transmitted in a mosquito, the Culex fatigans, Anopheles, or Aedes spp. The adult worm has a sheath that stains faintly or not at all. It may grow to approximately 298 μm in length by 2.5 μm to 10 μm wide. The tail is pointed with no nuclei present (Figure 53-4).