Blistering diseases

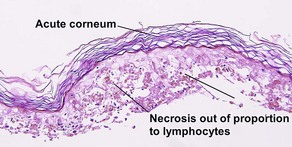

Subcorneal vesiculobullous disorders

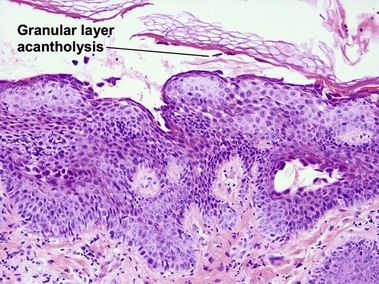

Pemphigus foliaceus

Pemphigus foliaceus is a subcorneal vesiculobullous disorder caused by autoantibodies directed at an intercellular keratinocyte adhesion protein, desmoglein 1 (160 kD). The disease usually presents with superficial crusted erosions upon the face and upper trunk. The superficial nature of the blisters makes them fragile and most patients lack intact bullae.

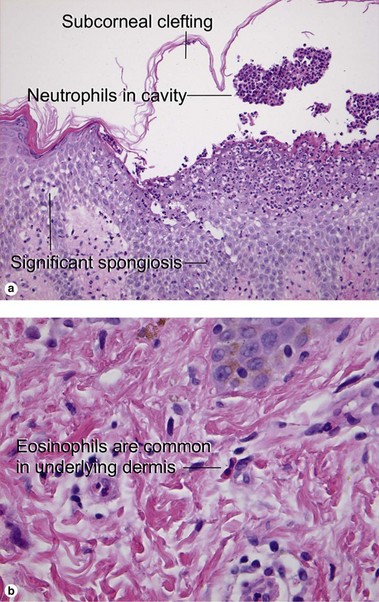

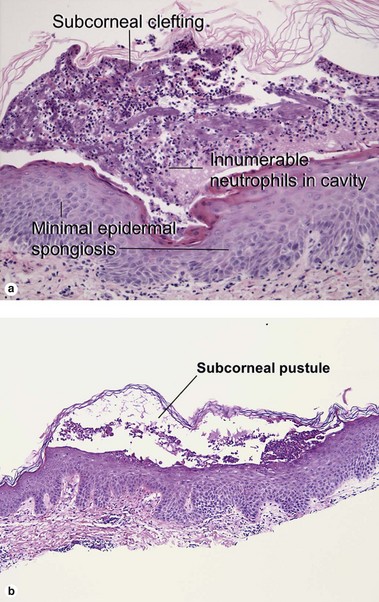

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson disease)

Fig 9-3 (a) Subcorneal pustular dermatosis. (b) “Subcorneal pustular dermatosis” type of IgA pemphigus

Cases of subcorneal pustular dermatosis with intercellular deposition of IgA have been reclassified as IgA pemphigus. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis may represent a subclass of pustular psoriasis, although mitotic figures within the underlying epidermis, common to psoriasis, are not identified in subcorneal pustular dermatosis. The classic patient is an older woman with annular or polycyclic lesions of the trunk or groin with pustules at the periphery.

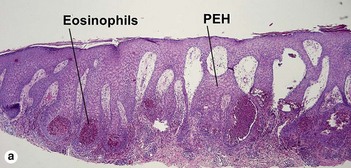

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon reaction to exogenous medications. Beta-lactam antibiotics are most often implicated, but a myriad of drug associations have been described. The presence of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate helps distinguish the condition from pustular psoriasis. Early pustules may be noted in association with hair follicles or sweat ducts.

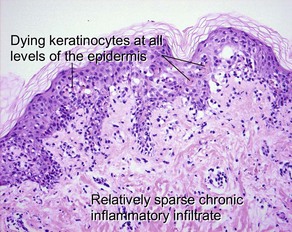

Intraepidermal vesiculobullous disorders

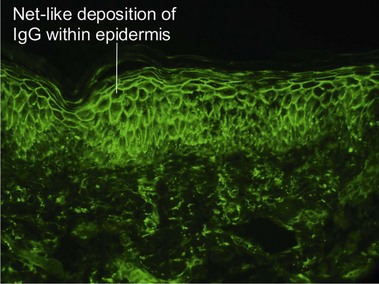

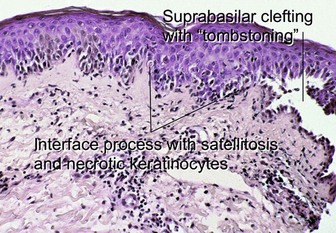

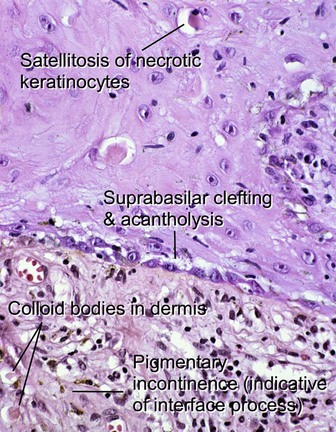

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is an intraepidermal vesiculobullous disorder caused by autoantibodies directed at an intercellular keratinocyte adhesion protein, desmoglein 3 (130 kD). The disease presents with erosions of the skin and mucosa. Often the disease begins in the posterior oropharynx weeks before cutaneous lesions are noted. Most patients lack intact bullae. Erythematous skin shears away easily when lateral pressure is applied (Nikolsky sign).

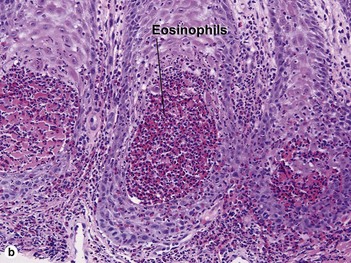

Familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey–Hailey disease)

Hailey–Hailey disease is an autosomal-dominant, inherited disease caused by mutations in the ATP2C1 gene. This gene encodes for a portion of a calcium pump essential for proper keratinocyte differentiation and adhesion. Skin of the intertriginous areas is most prominently affected and yields a clinical appearance likened to “wet tissue paper.” Acantholysis at all levels of the epidermis yields the histologic appearance of a “dilapidated brick wall.” While the disease itself is not immunologically mediated, superinfection of macerated skin by bacteria or yeast may engender an underlying inflammatory infiltrate within the superficial dermis.

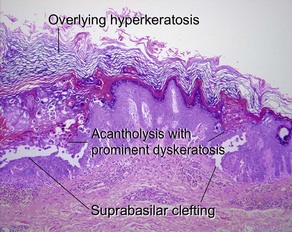

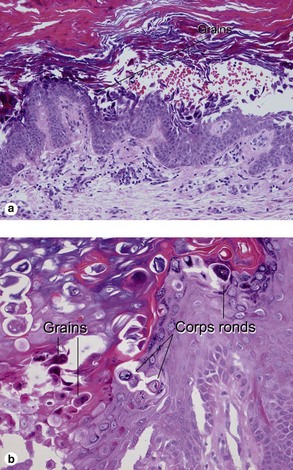

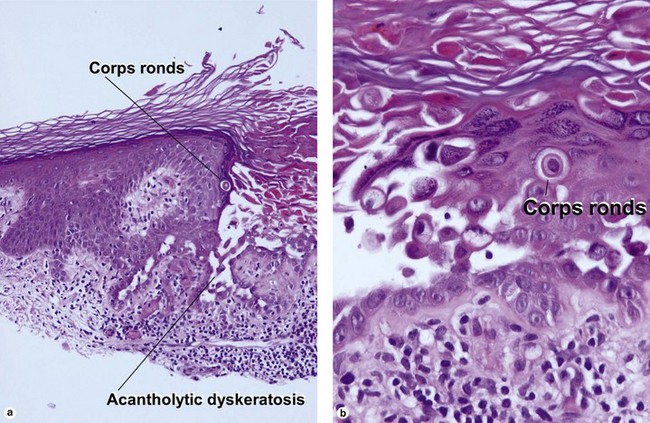

Keratosis follicularis (Darier’s disease)

The acantholysis results in suprabasal clefts (lacunae) that contain projections of papillary dermis covered by a single layer of basal cells (villi). There are two types of dyskeratotic cells. The granular layer and horny layer contain corps ronds, round dyskeratotic cells with pyknotic nuclei, a clear perinuclear halo, and pale to bright eosinophilic cytoplasm. Grains are seen in the granular layer as flattened basophilic dyskeratotic cells.

Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease)

More than one of these patterns may be found in the same specimen. The clinical presentation, the mixture of histologic patterns, and the focal nature of the lesions help distinguish the disease from the histologic mimics. Eosinophils, if present, aid in differentiation from Darier’s disease. Direct immunofluorescence is typically negative, in contrast to pemphigus.

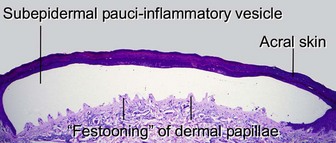

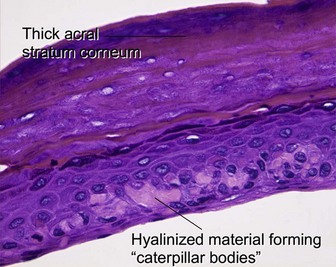

Subepidermal vesiculobullous disorders: pauci-inflammatory subepidermal conditions

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common form of porphyria in the USA. It is commonly associated with hepatitis C, alcohol ingestion, and iron overload. Inherited types result from reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in heme synthesis. Blisters, erosions, and milia occur on the hands and other photo-exposed locations.

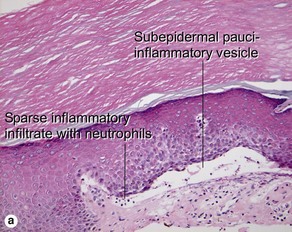

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

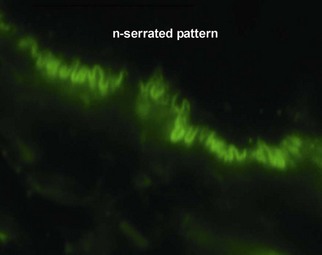

Fig 9-17 (a) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. (b) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, DIF showing characteristic u-serrated pattern (arrow).

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is caused by an antibody to type VII collagen, a major component of the anchoring fibrils. It is thought that deposition of immune complexes leads to the neutrophilic inflammation present in some specimens.

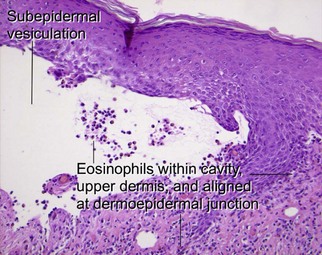

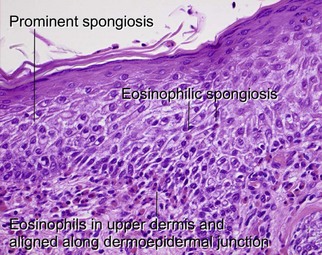

Inflammatory subepidermal conditions

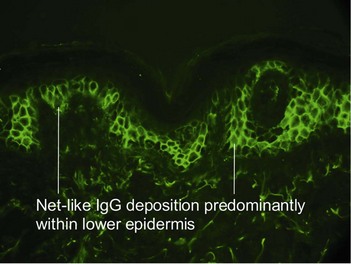

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid usually occurs in older patients, although children are occasionally affected. The disease is associated with autoantibodies to bullous pemphigoid antigen I (230 kD) and/or bullous pemphigoid antigen II (180 kD). The latter antigen is most clearly linked to pathogenesis. The subepidermal vesiculation results in firm and tense blisters. Intensely pruritic urticarial plaques, without clinically apparent vesiculation, may predate frankly bullous lesions (“urticarial pemphigoid”). Mucosal involvement is sometimes present, but, unlike pemphigus, it is rarely the first site of involvement.

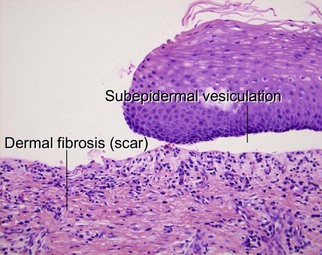

Cicatricial pemphigoid

Cicatricial pemphigoid refers to a heterogeneous group of scarring, subepidermal blistering disorders caused by a variety of autoantibodies. Tense bullae that heal with scarring are a common theme. Most subtypes involve oral or ocular mucosa. Recurring lesions may demonstrate extensive dermal scarring. Paraneoplastic variants have been described in the literature.

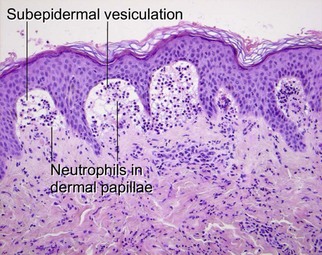

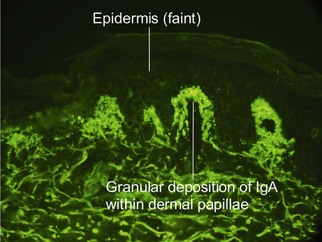

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is an intensely pruritic vesiculobullous disorder. Lesions are common upon the elbows, knees, buttocks, and scalp. Recent research indicates that epidermal transglutaminase-3 is the autoantigen in dermatitis herpetiformis. The disease is highly correlated with celiac sprue. Essentially, all patients have some level of gastrointestinal pathology, even if it is subclinical. Strict gluten-free diets prevent clinical manifestations of disease activity.

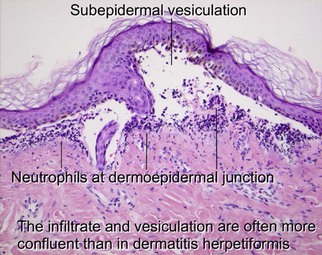

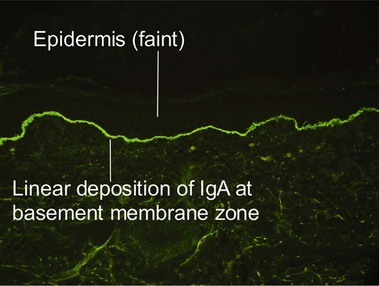

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis

Linear IgA is a heterogeneous subepidermal vesiculobullous disorder. In children, the disease is referred to as chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood. Both disorders are caused by autoantibodies targeting proteins (97–120 kD) that form as degradation products of bullous pemphigoid antigen II. Classically, the disease results in grouped annular lesions of tense bullae which have been likened to a “string of pearls.” Drug-induced cases have been described with vancomycin.

Chhabra, S, Minz, RW, Saikia, B. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012; 78(6):677–691.

Connor, BL, Marks, R, Jones, EW. Dermatitis herpetiformis: histologic discriminants. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1972; 58:191–198.

Fung, MA, Murphy, MJ, Hoss, DM, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of “caterpillar bodies” in the differential diagnosis of subepidermal blistering disorders. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003; 25:287–290.

Horn, TD, Anhalt, GJ. Histologic features of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1992; 128:1091–1095.

Jeong, SJ, Lee, CW. Bullous pemphigoid: persistent lesions of eczematous/urticarial erythemas. Cutis. 1995; 56:225–226.

Letko, E, Papaliodis, DN, Papaliodis, GN, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 94:419–436.

Liu, AY, Valenzuela, R, Helm, TN, et al. Indirect immunofluorescence on rat bladder transitional epithelium: a test with high specificity for paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993; 28:696–699.

Nishioka, K, Hashimoto, K, Katayama, I, et al. Eosinophilic spongiosis in bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1984; 120:1166–1168.

Quirk, CJ, Heenan, PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004; 45:83–86.

Sardy, M, Karpati, S, Merkl, B, et al. Epidermal transglutaminase (TGase 3) is the autoantigen of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Exp Med. 2002; 195:747–757.

Schmidt, E, Zillikens, D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013; 381(9863):320–332.

Tsuruta, D, Dainichi, T, Hamada, T, et al. Molecular diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2013; 961:17–32.

Yeh, SW, Ahmed, B, Sami, N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003; 16:214–223.