Chapter 18 Blind Digital Intubation

I History

Although it was probably first described by Herholdt and Rafn in 1796 for the management of drowning victims,1 blind digital orotracheal intubation did not receive much attention in the medical literature until its revival in emergency medicine and prehospital care by Stewart in the mid-1980s.2,3 Notable publications over the years have portrayed the technique as an acceptable, if not preferable, alternative to standard laryngoscopic endotracheal intubation, particularly when the standard technique is contraindicated, has failed, or is not possible because of a lack of equipment.

In 1880, Macewen described the technique utilizing a curved metal tube in awake patients,4 and Sykes5 recommended routine use of the digital technique in anesthetic practice in the 1930s. Siddall and Lanham relegated the technique to last-ditch efforts following the failure of conventional intubation methods.3,6,7 The technique has been described in neonatal resuscitation and as an adjunct in blind nasotracheal intubation.8–10

Currently, there is widespread variation in awareness, expertise, and application of the technique in anesthesia, emergency medicine,11,12 and prehospital care. Although advances in airway management equipment and expertise have made obsolete the routine use of blind digital orotracheal intubation, it remains a valuable skill in some situations, especially in the emergency setting or under circumstances in which the anesthesiologist cannot be positioned at the head of the patient,3 rendering laryngoscopic intubation impossible.

II Indications

1. When equipment required to undertake alternative techniques is unavailable or not functional.

2. When positioning of the patient or the anesthesiologist prevents conventional intubation.

3. When other methods have failed or are likely to fail and the skill and experience of the anesthesiologist make the digital technique a reasonable alternative.

4. In the presence of potential or actual cervical spine instability when the anesthesiologist selects the digital technique on the basis of the risk-benefit analysis. Although there is no evidence to suggest that the use of digital intubation alters the neurologic outcome of a patient, there may be less cervical spine motion during intubation with the digital technique compared with conventional laryngoscopic orotracheal intubation without in-line stabilization.

5. When adequate visualization of the airway to allow conventional intubation is not possible because of the presence of copious secretions, blood, or vomitus in the oropharynx or traumatic disruption of the upper airway anatomy.

III Technique of Digital Intubation

A Preparation

As with any intubation technique, preparation involves assembling the necessary equipment and personnel, including emergency drugs and adequate suction, to optimize success and preserve ventilation and oxygenation. An appropriately sized ETT is selected. The use of a stiff but malleable stylet improves maneuverability during the intubation. Lubrication of the stylet with a water-soluble lubricant ensures easy retraction after the tip of the ETT is placed in the glottic opening. The stylet is then inserted into the ETT so that the distal end of the stylet is at the level of the Murphy eye. With the stylet in place, the distal half of the styletted ETT unit (SETT) is bent into a “U” configuration (Fig. 18-1). The proximal half of the SETT is then bent approximately 90 degrees toward the dominant side of the ETT to allow manipulation of the SETT by the dominant hand during intubation (Figs. 18-2 and 18-3). The degree of bend should be individualized and is dependent on the anesthesiologist’s experience.

Figure 18-1 With the stylet in place, the distal half of the endotracheal tube is bent to a U shape.

C Technique

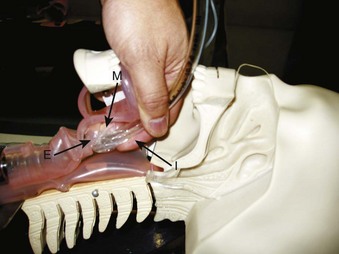

Pulling the tongue forward by an assistant facilitates palpation of the epiglottis, thus improving the success rate for digital intubation. The patient’s mouth is opened, and the tongue is grasped gently by the assistant with a piece of gauze (Fig. 18-4). Traction on the tongue moves the epiglottis slightly cephalad, enhancing its palpability and facilitating placement of the tip of the ETT into the glottic opening. The anesthesiologist then inserts the index and middle fingers of the nondominant hand into the oral cavity and slides the palm down along the surface of the tongue (Fig. 18-5). The tip of the middle finger touches the tip of the epiglottis, which is then directed anteriorly (Fig. 18-6). The ease of palpating and lifting the epiglottis depends on the length of the anesthesiologist’s fingers, the height of the patient, the anatomy of the oropharynx, and the presence or absence of teeth.

Figure 18-5 The index and middle fingers of the nondominant hand are inserted into the mouth with the palm facing down.

Once the epiglottis is identified and directed anteriorly, the SETT is inserted through the corner of the mouth. The SETT glides along the groove between the middle and index fingers on the palmar surface of the nondominant hand (see Fig. 18-3). While firm anterior pressure is maintained against the epiglottis with the middle finger, the SETT is advanced slowly into the glottic opening by the dominant hand. The index finger may be used to guide the tip of the SETT into the glottic opening (see Fig. 18-6).

The ETT should be stabilized while the stylet is withdrawn, and the ETT is then slowly advanced into the trachea. During the intubation, the SETT should never be advanced forcefully against resistance. Accurate placement is confirmed by conventional techniques, such as auscultation and carbon dioxide detection. Occasionally, the tip of the epiglottis cannot be palpated. An upward (cephalad) and backward (posterior) pressure applied anteriorly to the larynx by an assistant may be helpful (see Fig. 18-4). As an alternative, the index and middle fingers of the nondominant hand may be used to keep the SETT in the midline while tissue movement in the anterior neck is observed during gentle rocking of the SETT back and forth in an attempt to locate the glottic opening.

An alternative technique described by Cook begins with placement of the index and middle finger tips of the nondominant hand in the hypopharynx, posterior to the larynx.13 The ETT held in the dominant hand is then passed into the pharynx. The volar surfaces of the fingers serve as a “basketball backstop” to guide the ETT held in the dominant hand through the glottic opening. If required, the index finger of the nondominant hand may be flexed to help guide the ETT through the glottis.

D Tracheal Introducer–Assisted Digital Intubation

A recent case report highlighted the use of a tracheal introducer (commonly known as “bougie”) in facilitating a digital intubation technique in a patient with an unanticipated difficult airway after direct laryngoscopy attempts were unsuccessful.14 A SunMed ETT Introducer (SunMed, Largo, FL) was first guided into the trachea using the digital technique. Tracheal clicks were used to confirm successful placement of the introducer in the trachea. The ETT was then guided into the trachea using the introducer as conduit.

E Neonatal Digital Intubation

Blind digital intubation in neonates has not gained widespread acceptance as a primary technique of intubation. Moura and associates performed a randomized controlled trial comparing laryngoscopic intubation with the digital method in neonates.15 They found that neonatal digital intubation had a higher success rate and a shorter intubation time. A single experienced anesthesiologist was responsible for performing all the procedures, and this was identified as a study limitation.

Neonatal digital intubation has been used in several third-world countries where experience with and access to standard laryngoscopes are limited.8 Hancock and Peterson used the blind digital intubation technique in neonatal resuscitation and accidental extubation situations.16 The anesthesiologist uses the gloved index finger of the nondominant hand to identify the epiglottis and glottic opening. The index finger is then used to guide the ETT through the glottic opening. The thumb of the nondominant hand can be used to apply external cricoid pressure. A SETT is recommended. The fifth finger of the nondominant hand can be used in very small neonates.

F Combined Techniques

The technique of blind digital intubation has been combined with the BAAM Whistle (Beck Airway Airflow Monitor, Great Plains Ballistics, Lubbock, TX) and the Endotrol tube (Mallinckrodt Medical, Argyle, NY) to facilitate endotracheal intubation in several situations after failure of direct laryngoscopy.17,18 The BAAM device was initially developed to facilitate the teaching of blind nasotracheal intubation techniques under spontaneous ventilation. The BAAM produces a whistling sound of slightly different pitches during inspiration and expiration if the ETT is positioned within the air column leaving or entering the trachea. The device has also been shown to be effective in guiding nasotracheal tube placement in situations in which external cardiac massage is being applied.18

In fiberoptic intubation, it can be difficult to advance the ETT into the trachea. Asai and colleagues reported use of the digital technique to help guide a 39-F double-lumen tube off the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope and into the trachea of a patient undergoing an anterior thoracic laminectomy procedure.19 The anatomy of the patient’s airway and that of the anesthesiologist’s hand are key determinants in deciding which technique should be used in a given situation.

Light-guided endotracheal intubation using the Trachlight (Laerdal Medical, Wappingers Falls, NY) can be difficult in patients who have a long and floppy epiglottis.20 This difficulty can be overcome by using the combined light-guided digital intubating technique. During the intubation, the middle finger of the nondominant hand can be used to lift the epiglottis off the posterior wall of the pharynx to allow the ETT with the Trachlight to go underneath the epiglottis into the glottic opening. The light glow at the anterior neck can be used to confirm the correct placement of the ETT tip into the glottis. During the past several years, we have performed more than 20 intubations using this combined light-guided digital intubating technique. The lightwand-guided intubation technique has also been described in newborns and infants with difficult airways.21

Digital assistance for nasotracheal intubation has been reported in the pediatric population to facilitate atraumatic passage of the tube behind the soft palate and entrance into the trachea.22 However, this technique has not been systematically studied in a randomized controlled trial.

V Limitations

Digital intubation in uncooperative patients is generally difficult. The more alert the patient is, the less likely it is that digital intubation will be tolerated or successful. Patients with limited mouth opening, carious or prominent dentition, a small mouth, or a large tongue, as well as very tall patients, can be predictably difficult to intubate regardless of the method employed, including the digital method. With practice, however, digital intubation has been shown to be an effective alternative method of intubation.18

VII Clinical Pearls

• Blind digital intubation should be considered as an airway management technique when alternative options are either unavailable or not functional.

• The technique may be considered in situations in which positioning for conventional intubation is not possible or soiling of the airway limits visualization of the larynx and glottis inlet.

• Universal infectious disease precautions must be taken at all times, and the patient’s level of consciousness and state of paralysis must always be kept in mind.

• Pulling the tongue forward by an assistant during the technique facilitates traction on the epiglottis, thereby improving the overall chance of successful intubation.

• Blind digital intubation may be facilitated by the use of a tracheal introducer or bougie that produces confirmatory tracheal clicks before railroading of the ETT.

• Various intubation devices and techniques (e.g., BAAM whistle, Endotrol ETT, Trachlight, nasotracheal intubation, double-lumen ETT intubation) may be combined and facilitated by blind digital intubation.

• Successful ETT placement in the trachea after blind digital intubation should be confirmed with carbon dioxide detection devices.

• Experience with blind digital intubation in elective settings with patients who are anesthetized and paralyzed will enhance the clinician’s skill acquisition and confidence in performance of the technique.

All references can be found online at expertconsult.com.

2 Stewart RD. Tactile orotracheal intubation. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:175–178.

5 Sykes WS. Oral endotracheal intubation without laryngoscopy: A plea for simplicity. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1937;16:133.

10 Korber TE, Henneman PL. Digital nasotracheal intubation. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:275–277.

13 Cook RT, Jr. Digital endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:396.

14 Rich JM. Successful blind digital intubation with a bougie introducer in a patient with an unexpected difficult airway. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2008;21:397–399.

15 Moura JH, da Silva GA. Neonatal laryngoscope intubation and the digital method: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2006;148:840–841.

16 Hancock PJ, Peterson G. Finger intubation of the trachea in newborns. Pediatrics. 1992;89:325–327.

17 Cook RT, Jr., Polson DL. Use of BAAM with a digital intubation technique in a trauma patient. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1993;8:357–358.

21 Xue FS, Liu JH, Zhang YM, et al. The lightwand-guided digital intubation in newborns and infants with difficult airways. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:702–704.

22 Mahajan R, Kumar S, Kumar Batra Y. Digital assistance of nasotracheal intubation: Another way to prevent trauma during nasotracheal intubation. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17:703.

1 Herholdt JD, Rafn CG. Life-saving measures for drowning persons. Copenhagen: H Tikiob; 1796.

2 Stewart RD. Tactile orotracheal intubation. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:175–178.

3 Stewart RD. Digital intubation. In: Dailey RH, Simon B, Stewart RD, et al. The airway: Emergency management. St. Louis: Mosby; 1992:111–114.

4 Macewen W. Clinical observations on the introduction of tracheal tubes by the mouth instead of performing tracheostomy or laryngotomy. Br Med J. 1880;122:163.

5 Sykes WS. Oral endotracheal intubation without laryngoscopy: A plea for simplicity. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1937;16:133.

6 Siddall WJ. Tactile orotracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 1966;21:221–222.

7 Lanham HG. Tactile orotracheal intubation. JAMA. 1976;236:2288.

8 Wijesundera CD. Digital intubation of the trachea. Ceylon Med J. 1990;35:81–82.

9 Woody NC, Woody HB. Direct digital intratracheal intubation for neonatal resuscitation. J Pediatr. 1968;73:903–905.

10 Korber TE, Henneman PL. Digital nasotracheal intubation. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:275–277.

11 Hardwick WC, Bluhm D. Digital intubation. J Emerg Med. 1984;1:317–320.

12 Hartmannsgruber MW, Gabrielli A, Layon AJ, et al. The traumatic airway: The anesthesiologist’s role in the emergency room. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2000;38:87–104.

13 Cook RT, Jr. Digital endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:396.

14 Rich JM. Successful blind digital intubation with a bougie introducer in a patient with an unexpected difficult airway. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2008;21:397–399.

15 Moura JH, da Silva GA. Neonatal laryngoscope intubation and the digital method: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2006;148:840–841.

16 Hancock PJ, Peterson G. Finger intubation of the trachea in newborns. Pediatrics. 1992;89:325–327.

17 Cook RT, Jr., Polson DL. Use of BAAM with a digital intubation technique in a trauma patient. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1993;8:357–358.

18 Cook RT, Jr., Stene JK, Marcolina B, Jr. Use of a Beck Airway Airflow Monitor and controllable-tip endotracheal tube in two cases of nonlaryngoscopic oral intubation. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:180–183.

19 Asai T, Matsumoto S, Shingu K. Use of the McCoy laryngoscope or fingers to facilitate fibrescope-aided tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:903–905.

20 Hung OR, Pytka S, Morris I, et al. Clinical trial of a new lightwand device (Trachlight) to intubate the trachea. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:509–514.

21 Xue FS, Liu JH, Zhang YM, et al. The lightwand-guided digital intubation in newborns and infants with difficult airways. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:702–704.

22 Mahajan R, Kumar S, Kumar Batra Y. Digital assistance of nasotracheal intubation: Another way to prevent trauma during nasotracheal intubation. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17:703.