Bites and stings

This chapter presents strategies for the prevention and management of bites and stings.

Specific investigations

Molecular characterization of Swiss Ceratopogonidae (Diptera) and evaluation of real-time PCR assays for the identification of Culicoides biting midges.

Wenk CE, Kaufmann C, Schaffner F, Mathis A. Vet Parasitol 2012; 184: 258–66.

The assays require improvement, but are promising for identification of small species of insects.

Usefulness of post mortem determination of serum tryptase, histamine and diamine oxidase in the diagnosis of fatal anaphylaxis.

Mayer DE, Krauskopf A, Hemmer W, Moritz K, Jarisch R, Reiter C. Forensic Sci Int 2011; 212: 96–101.

Elevated tryptase levels above 45 µg/L may support the diagnosis of fatal anaphylaxis.

First-line therapy

Second-line therapies

Third-line therapies

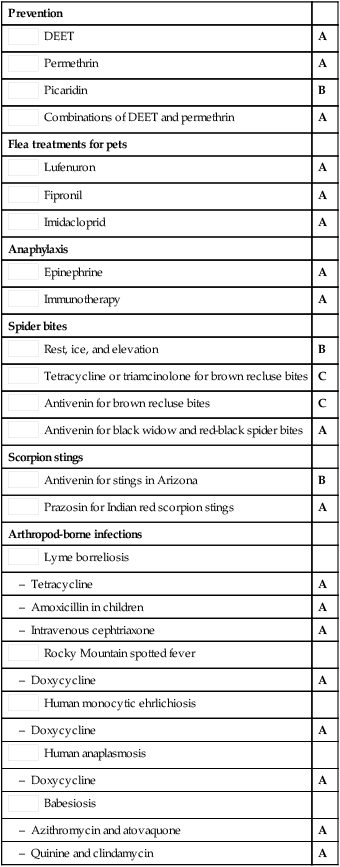

DEET

DEET Permethrin

Permethrin Picaridin

Picaridin Combinations of DEET and permethrin

Combinations of DEET and permethrin Lufenuron

Lufenuron Fipronil

Fipronil Imidacloprid

Imidacloprid Epinephrine

Epinephrine Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy Rest, ice, and elevation

Rest, ice, and elevation Tetracycline or triamcinolone for brown recluse bites

Tetracycline or triamcinolone for brown recluse bites Antivenin for brown recluse bites

Antivenin for brown recluse bites Antivenin for black widow and red-black spider bites

Antivenin for black widow and red-black spider bites Antivenin for stings in Arizona

Antivenin for stings in Arizona Prazosin for Indian red scorpion stings

Prazosin for Indian red scorpion stings Lyme borreliosis

Lyme borreliosis Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever Human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis Human anaplasmosis

Human anaplasmosis Babesiosis

Babesiosis

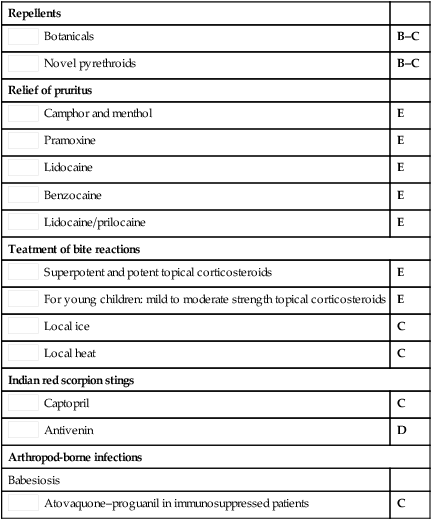

Botanicals

Botanicals Novel pyrethroids

Novel pyrethroids Camphor and menthol

Camphor and menthol Pramoxine

Pramoxine Lidocaine

Lidocaine Benzocaine

Benzocaine Lidocaine/prilocaine

Lidocaine/prilocaine Superpotent and potent topical corticosteroids

Superpotent and potent topical corticosteroids For young children: mild to moderate strength topical corticosteroids

For young children: mild to moderate strength topical corticosteroids Local ice

Local ice Local heat

Local heat Captopril

Captopril Antivenin

Antivenin Atovaquone–proguanil in immunosuppressed patients

Atovaquone–proguanil in immunosuppressed patients

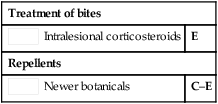

Intralesional corticosteroids

Intralesional corticosteroids Newer botanicals

Newer botanicals