30 Bipolar Disorder

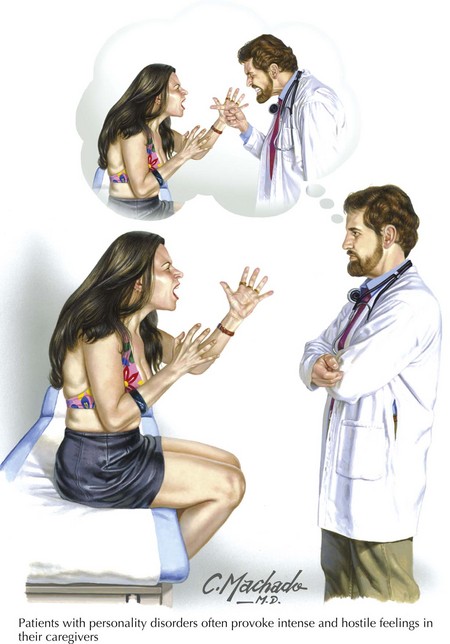

Typically mania has a unique presentation. The patient is often colorfully dressed and wearing too much jewelry, is excessively cheerful, overly familiar, brimming with schemes and ideas, and does not stop talking (Fig. 30-1). One of the surest sign of mania is the physician feeling the need to interrupt the patient. In the extreme, manic patients lose touch with reality; they may declare themselves an emperor, suddenly relocate to another state, or flirt dangerously with strangers. These patients often become irritable and sometimes aggressive. They may stop sleeping. In contrast to schizophrenic patients, who seem odd and distant, manic patients are often humorous, and frequently engaging.

Clinical Presentation

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Pr.; 2007.

Jamison KR. An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York, NY: Vintage; 1997.

Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Ghaemi SN, et al. Adjunctive antidepressant use and symptomatic recovery among bipolar depressed patients with concomitant manic symptoms: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;164(9):1348-1355.

Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a STEP-BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):210-216.

Owen C, Rees AM, Parker G. The role of fatty acids in the development and treatment of mood disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;21(1):19-24.

Wilens TE, Biederman J, Adamson JJ, et al. Further evidence of an association between adolescent bipolar disorder with smoking and substance use disorders: A controlled study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Mar 14.