Chapter 46 Bile duct cysts in adults

Bile Duct Cysts

Bile duct cysts typically are a surgical problem of infancy or childhood (Altman, 1994); however, in nearly 20% of patients, the diagnosis is delayed until adulthood. Although clinically similar, the presentation and therapeutic strategies for bile duct cysts in adults may differ substantially from those of younger patients. In contrast to the pediatric experience, adult patients have an increased rate of associated hepatobiliary pathology (Nagorney et al, 1984a; Powell et al, 1981; Rattner et al, 1983), and they often are first seen with complications of previous cyst-related procedures (Gigot et al, 1996; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982; Todani et al, 1984a). The surgical management of bile duct cysts in adults is thus complicated by coexisting hepatobiliary disease and the added technical difficulties of reoperative biliary surgery. Despite the heterogeneity of the disease and the absence of clinical trials, a consensus on the management of extrahepatic bile duct cysts has been established: excision is best. However, the management of intrahepatic bile duct cysts remains problematic, and the method of choice for reestablishing bilioenteric continuity after excision is debatable. This chapter examines the spectrum of hepatobiliary pathology encountered in adults with bile duct cysts and describes the alternative surgical approaches for managing such patients.

Diagnosis

Classification

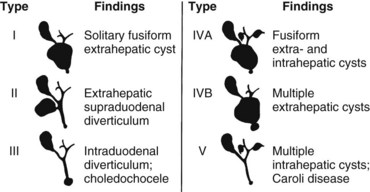

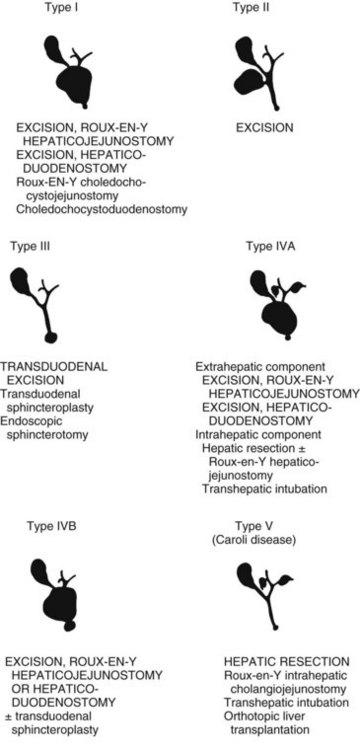

Bile duct cysts are classified on the basis of site, extent, and shape of the cystic anomaly of the ductal system. Although the term choledochal cyst is often used, bile duct cyst is semantically more appropriate because cystic dilation can occur anywhere throughout the biliary ductal system, not just in the common bile duct (choledochus). The first coherent classification of extrahepatic bile duct cysts was proposed by Alonso-Lej and colleagues in 1959. Cysts were classified into three types: type I is a fusiform or saccular dilation of the common hepatic and common bile duct, type II is a supraduodenal diverticulum of the common hepatic or common bile duct, and type III is an intraduodenal diverticulum of the distal common bile duct or choledochocele. Although this classification did not include intrahepatic bile duct cysts, this simple and practical scheme has provided the basis for all other classification systems.

The recognition of intrahepatic bile duct cysts prompted modification of the Alonso-Lej classification system, and in 1958, Caroli and colleagues described the entity of multiple intrahepatic bile duct cysts in the absence and presence of extrahepatic cysts. Although initially described as an entity of multiple saccular dilations of only the intrahepatic ducts, the term Caroli disease has been broadly applied to describe any patient with intrahepatic bile duct cysts, regardless of the presence of extrahepatic bile duct cysts or the shape of the intrahepatic cysts (Dayton et al, 1983). Caroli disease represents a spectrum of diseases that may include such variants as cysts with congenital hepatic fibrosis or Grumbach disease (see Chapter 70A; Grumbach et al, 1954). Todani refined the classification system of bile duct cysts by combining the Alonso-Lej classification and the variants of Caroli disease (Todani et al, 1977). The comprehensive Todani classification system is shown in Fig. 46.1.

Matsumoto also modified the Alonso-Lej classification system based not only on the location of the cyst but also on the configuration of cysts (Matsumoto et al, 1977a). To date, clinical management of bile duct cysts is dictated by cyst location, not configuration; therefore there is little clinical rationale for adoption of the more detailed classification scheme (Kamisawa et al, 2005; Komi et al, 1992; Matsumoto et al, 1977b), although further additions to the Todani classification have been suggested (Calvo-Ponce et al, 2008; Conway et al, 2009).

Etiology

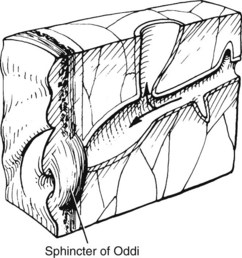

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the origin of bile duct cysts. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that cystic dilation of the bile ducts is related to an anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ductal junction (Babbitt, 1969; Cheng et al, 2004; Komi et al, 1992; Okada et al, 1990; Todani et al, 1984b; Wiedmeyer et al, 1989). The pancreaticobiliary junction is proximal to the sphincter of Oddi (Fig. 46.2) (Nagata et al, 1986). An anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction is often associated with a long common channel that predisposes to reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tree, leading to inflammation, ectasia, and, ultimately, to dilation. This postulate has been supported by biliary manometric studies (Iwai et al, 1986), high concentrations of pancreatic enzymes in cyst fluid (Todani et al, 1990), and histopathologic studies of ductal epithelial hyperplasia, round cell infiltration, and marked ductal fibrosis (Oguchi et al, 1988). Moreover, experimental canine studies of pancreaticocholecystostomy and pancreaticocholedochostomy have resulted in cystic dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct (Oguchi et al, 1988; Ohkawa et al, 1981). Pancreaticobiliary maljunction, or anomalous union, defined as union of the pancreatic and biliary duct outside of the duodenal wall, has also been implicated in biliary tract cancer even in the absence of a biliary cyst (Funabiki et al, 2009; Horaguchi et al, 2005).

Reports of choledochal cysts of the same type in family members suggest that a hereditary factor may contribute, albeit rarely, to bile duct cysts (Iwafuchi et al, 1990). Finally, oligoganglionosis in the distal neck of the cyst may account for some bile duct cysts. The reduction in ganglion cells in the narrow portion of the cyst wall may be the biliary equivalent of Hirschsprung disease of the colon (Kusunoki et al, 1988).

Demographics

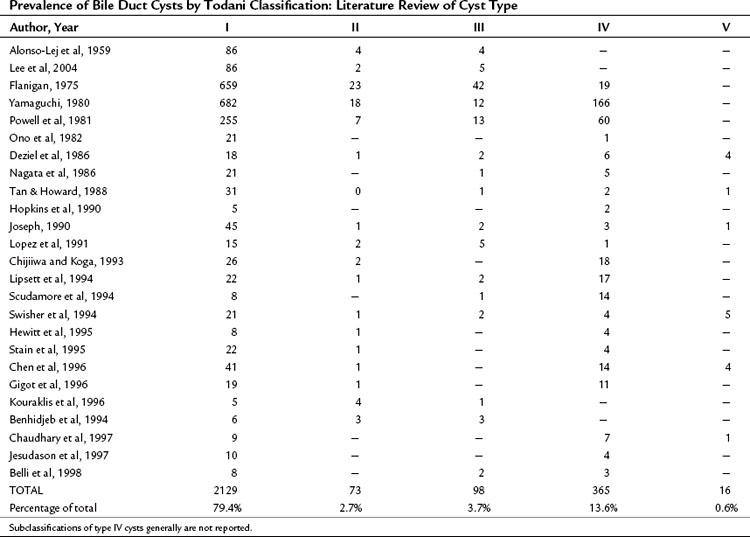

Bile duct cysts are an uncommon finding, with fewer than 4000 cases reported (Flanigan, 1975; Powell et al, 1981; Yamaguchi, 1980). Estimates of the actual clinical incidence range from one in 13,000 to one in 2 million patients (Olbourne, 1975), and biliary cysts account for approximately 1% of all benign biliary disease (Saxena et al, 1988). The estimated prevalence of bile duct cysts by type (Todani classification), based on a review of the current literature, is shown in Table 46.1. The true prevalence of bile duct cysts by current classification schemes is underestimated here because classification is often not detailed. The frequency of bile duct cyst in decreasing order is the type I choledochal cyst (79%), followed by type IV (13%), then type III, or choledochocele (4%), and type II (2.6%). Multiple intrahepatic bile duct cysts without an extrahepatic component (Caroli disease) occur in fewer than 1% of all patients with biliary cystic disease. The distribution of cyst types encountered in adults is similar to that in infants and children (Gigot et al, 1996; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982), except type IV cysts are more frequent in adults (Todani et al, 1978, 1984a).

A marked population prevalence has been seen in Japan (Flanigan, 1975; Powell et al, 1981; Yamaguchi, 1980), where more than one third of reported cases have occurred. Although the number of reported cases has increased recently, this finding probably reflects advances in diagnosis through improvements in hepatobiliary imaging rather than a true increase in incidence.

A female preponderance among patients with bile duct cysts is well known, regardless of cyst type. In Flanigan’s (1975) collected series of 820 cases, 81% of the patients were female. A similar female/male ratio has been found in adults (Powell et al, 1981). Current theories on the pathogenesis of bile duct cysts have not implicated sex hormones or congenital intrauterine endocrine disturbances as possible factors.

Clinical Features

Choledochal cysts may remain asymptomatic for many years. Initial clinical presentation in adulthood (age >16 years) occurs in fewer than 20% of all patients with common duct cysts (Flanigan, 1975). Diagnosis may be an incidental finding on imaging studies for unrelated processes. If symptomatic, bile duct cysts usually present with symptoms mimicking calculous biliary tract disease, regardless of cyst type. Symptoms are typically intermittent, recurrent epigastric or right hypochondrial pain, abdominal tenderness, fever, and mild jaundice—the most common initial findings. The pain may radiate to the right infrascapular region or to the mid back, and it generally persists for hours. Abdominal pain or discomfort is often overshadowed by fever and rigors, which may occur repeatedly for several days. An abdominal mass is uncommon in adults; however, if a mass is present, cyst-associated malignancy must be strongly suspected. Biliuria heralds the onset of clinical jaundice. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia may accompany other symptoms; if cholangitis persists, the jaundice deepens and overt signs of sepsis may evolve.

Clinical pancreatitis is present in nearly 30% of patients with choledochal cysts (Nagorney et al, 1984a). In contrast to patients with cholangitis, patients with pancreatitis have more intense and prolonged epigastric pain and vomiting. Fever and jaundice are less prominent. Weight loss, although unusual, is noteworthy because nearly 70% of adults with this finding will harbor an associated bile duct malignancy (see Chapter 50B).

Imaging

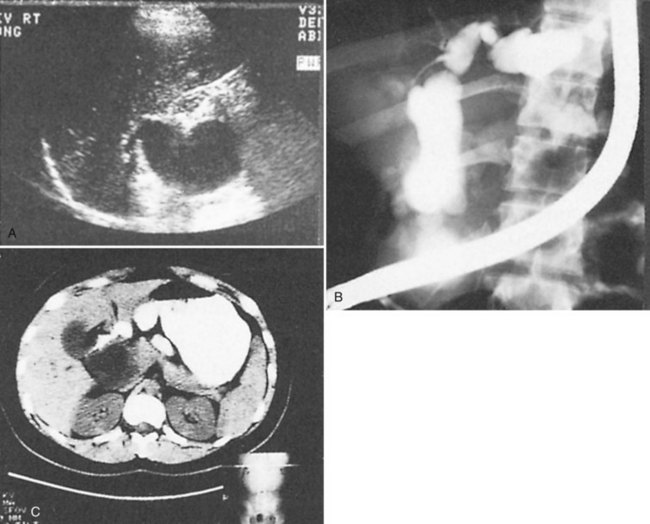

Accurate preoperative diagnosis can be achieved by using the routine diagnostic armamentarium for patients with suspected biliary tract disease: abdominal ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) (Fig. 46.3). Current reviews of the diagnostic imaging modalities of bile duct cysts with representative images are referenced (Kim et al, 1995; Savader et al, 1991a, 1991b). Although hepatobiliary scintigraphy has also been useful in identifying bile duct cysts, its value is limited because the information is functional and not anatomic; it is therefore only complementary to US, CT, and direct cholangiography. In general, bile duct cysts are typically recognized serendipitously in adults, unless a past diagnosis had been established before adulthood.

The noninvasiveness and accuracy of US, combined with its ability to image adjacent viscera, support its use as the initial investigative procedure (see Chapter 13). Real-time US is favored because of its speed and ease of application. Moreover, the ability of real-time US to scan multiple planes adds a distinct advantage in defining the extent of the dilation. The sonographic features of choledochal cysts have been well defined for type I choledochal cysts and the variants of Caroli disease (Bass et al, 1977; Morgan et al, 1980; Todani et al, 1978; Young et al, 1990). US of type I cysts simply shows an irregular hypoechoic segmental dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct. Focal duct wall thickening or nodularity should arouse suspicion for cancer in an adult. Stones within the cyst can also be identified by typical echogenic features and acoustic shadowing. The absence of septations on US will distinguish choledochal cysts from extrahepatic biliary tumors, such as cystadenomas (Nagorney et al, 1984b). Although the sensitivity of US is excellent for cysts involving the bile duct proximal to the pancreas, US is limited in adults in identifying choledochoceles because of the small size of these cysts and the frequency of bowel gas overlying the terminal common bile duct.

Caroli disease is clinically recognized by multiple cysts adjacent to the major intrahepatic bile ducts on US (Bruneton et al, 1983). Cysts may be unilobar or bilobar, and confirmation of communication of the intrahepatic cysts to the bile ducts can be confirmed by scintigraphy (Sty et al, 1978) or using CT with biliary contrast medium (Musante et al, 1982).

CT combined with intravenous cholangiography is useful for demonstration of cyst communication with the biliary tract (see Chapter 16; Hoglund et al, 1990). Intravenous cholangiography is performed 2 hours before abdominal CT scanning. The sensitivity of CT allows for accurate identification of accumulated contrast material within the cyst, if communication is present, and for accurate definition of the bile duct cyst (Tohma et al, 2009).

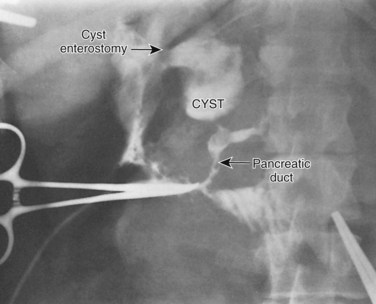

Direct cholangiography is the preferred diagnostic modality for accurate definition of the type of choledochal cyst (see Chapter 18). Indeed, cyst classification is based on cholangiographic features (Matsumoto et al, 1977a; Todani et al, 1977). All bile duct cysts communicate with the ductal system. Direct cholangiography is a prerequisite to operation because it has the advantage of being able to define the configuration and extent of the cyst; it also can identify ductal strictures, stones within the biliary and pancreatic ducts, and polypoid filling defects that suggest ductal malignancy. In addition, direct cholangiography is essential in defining the relationship of the distal bile duct in the type I cyst or the extrahepatic component of type IVA cyst to the pancreatic duct. The base of the extrahepatic choledochal cyst typically joins the pancreatic duct 2 to 4 cm proximal to the duodenum (Fig. 46.4), resulting in a long common channel (ampulla) (Jona et al, 1979; Komi et al, 1992; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983). The angle of fusion between the distal bile duct and pancreatic duct varies widely and has led to subclassifications of cyst type (Komi et al, 1992). Anatomic definition of the pancreatic biliary ductal junction is of key importance to avoid intraoperative damage of the pancreatic duct during cyst excision, recognize stones impacted within the common channel or junction, and exclude distal tumors. Regardless of method, complete cholangiographic visualization of the entire biliary and pancreatic ductal systems is essential in patients with choledochal cysts because failure to recognize pancreatic duct anomalies or segmental areas of dilation within the liver parenchyma may lead to sepsis, subsequent cholangitis, pain, pancreatitis, and eventual reoperation.

There are advantages and disadvantages of PTC and ERCP for assessing choledochal cysts. Regardless of method, large volumes of radiographic contrast may be required for complete visualization of the bile ducts. Adults without previous cystenterostomy are probably best evaluated by ERCP because it provides better visualization of an abnormal pancreaticobiliary ductal junction (Savader et al, 1991b; Komi et al, 1992). Carcinoma can be excluded by biopsy or brush cytology, and intracystic stones can be extracted after papillotomy to relieve severe cholangitis before surgery. Endoscopy also allows visualization of the esophagus and stomach to exclude signs of portal hypertension. The endoscopist should attempt to examine the ductal bifurcation and the lining of the cyst, if a patent cystoduodenostomy allows introduction of the endoscope into the biliary tree. Endoscopically directed biopsy of intracystic masses should be performed to exclude malignancy. Obstructing balloons should be available to ensure that complete radiographic filling of the biliary tree is possible, especially in patients with prior cystoduodenostomy. Endoscopy of the cyst through a cystenterostomy may also permit diagnosis of intraductal stenoses by membranes or septa at the confluence of the major bile ducts in patients with type IVA cysts (Ando et al, 1995). The procedure of choice for type III cysts or choledochoceles is ERCP because endoscopic papillotomy is potentially therapeutic (Sarris & Tsang, 1989; Venu et al, 1984).

PTC is an effective alternative to ERCP in the diagnosis of choledochal cysts. Because of endoscopic limitations imposed by the Roux-en-Y jejunal limb, PTC is particularly advantageous in patients with previous Roux-en-Y cystenterostomy and in patients with type IV bile duct cysts, in whom ductal strictures or tumors prevent complete visualization of intrahepatic cysts by ERCP (Savader et al, 1991b). The major diagnostic disadvantage of PTC is occasional failure to clearly define the pancreaticobiliary junction. Percutaneous biliary drainage (PBD) may be performed after PTC when indicated for control of biliary sepsis or to aid surgical reconstruction. PTC is particularly limited in patients with a widely patent cystenterostomy or huge extrahepatic cysts, because intracystic contrast is often superimposed over the pancreaticobiliary junction and obscures its radiographic definition.

MRC provides a noninvasive method of imaging the bile ducts and its anomalies (see Chapter 17), and it has been shown to provide an accurate anatomic definition of bile duct cysts in neonates, infants, and young children (Fitoz et al, 2007; Miyazaki et al, 1998). In a recent study, MRC reliably diagnosed biliary cystic disease in 74 (96%) of 76 patients with an accuracy of 86% for ductal anomalies (Park et al, 2005); however, it was less effective in detecting minor ductal anomalies and small cysts (Shaffer, 2006). MRC application to adults can be anticipated because image acquisition in adults is not hindered by the technical difficulties met when performing these studies in children. The limitation of MRC for bile duct cysts has related to its inability to clearly define the pancreaticobiliary junction (diagnostic accuracy, 69%) and its lack of therapeutic capability.

Associated Hepatobiliary Pathology

Additional hepatobiliary pathology is frequently associated with bile duct cysts in adults. Cystolithiasis, hepatolithiasis, calculous cholecystitis, pancreatitis, cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic abscess, and cirrhosis with portal hypertension are potential problems that may either precipitate or complicate treatment. Although spontaneous perforation of bile duct cysts has been reported in infants and children, that complication has not been recognized in adults (Ando et al, 1998). Studies in adults suggest that nearly 80% of adults with bile duct cysts have complications from one or more of the conditions listed above (Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982). A recent study suggests that complications in adults may decrease if excision is used routinely in infants and children (Gigot et al, 1996).

Cystolithiasis is the most frequent accompanying condition in adults with bile duct cysts. In contrast to the low prevalence of cystolithiasis in pediatric patients (Flanigan, 1975; Matsumoto et al, 1977a, 1977b; Rattner et al, 1983), the prevalence of intracystic stones has ranged from 2% to 72% in adults (Chijiiwa & Koga, 1993; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Todani et al, 1988). Although their composition has not been analyzed biochemically, most intracystic stones have been described as soft, earthy, and pigmented in appearance, thus supporting bile stasis as a primary etiologic factor (Matsumoto et al, 1977a, 1977b). These stones typically are associated with thick, viscous bile that may form bile duct or cyst casts. Cystolithiasis frequently complicates anastomotic strictures after previous cystoenterostomies, which suggests that stasis and infection are major factors contributing to the pathogenesis of these stones.

Hepatolithiasis has been recognized with increasing frequency with long-term follow-up and may occur with or without evidence of anastomotic stricture (Fig. 46.5) (see Chapter 7; Deziel et al, 1986; Gigot et al, 1996; Uno et al, 1996). Some patients will have a complete or partial stricture of the cystenteric anastomosis, and hepatolithiasis develops as a consequence of proximal bile stasis or migration of intracystic stones. Hepatolithiasis usually occurs in type IV bile duct cysts. A recent study has shown that more than 80% of type IV bile duct cysts are associated with either a membranous or septal stenosis of the major lobar bile ducts near the confluence (Ando et al, 1995). Stenosis of the major ducts should be assessed in all patients with hepatolithiasis. Intrahepatic stones may be sequestered in segmental ducts, leading to further localized intrahepatic ductal dilation or subsequent intrahepatic abscess formation.

The association of pancreatitis with choledochal cysts is a well-recognized entity, particularly in adults (see Chapter 53). The prevalence has ranged from 2% to 70% (Lipsett et al, 1994; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Okada et al, 1990; Rattner et al, 1983; Swisher et al, 1994). The true incidence of pancreatitis is difficult to determine because the diagnosis is based on the clinical findings of epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting, and hyperamylasemia. Another clinical condition, the common channel syndrome (Jona et al, 1979) or pseudopancreatitis (Todani et al, 1990), may mimic these findings completely, thus overestimating the true incidence of pancreatitis. Whether differentiation between these two entities has clinical or therapeutic significance is unclear. Pancreatitis associated with bile duct cysts typically is mild. The pattern of pancreatitis is acute and often relapsing, but objective pancreatic dysfunction seldom occurs. Chronic pancreatitis associated with bile duct cysts is rare.

The pathogenesis of pancreatitis in patients with choledochal cysts is primarily related to the anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal anatomy and the presence of cystolithiasis or cholelithiasis. Several authors have confirmed that the base of the extrahepatic cyst or distal common bile duct in type I or IV cysts joins the main pancreatic duct more proximally than normal, resulting in a long common channel (Jona et al, 1979; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983; Swisher et al, 1994). Obstruction of the pancreatic duct at the pancreaticobiliary junction or distally in the common channel (ampulla) by stones is postulated as the precipitating factor. A few studies (Nagorney et al, 1984a; Rattner et al, 1983) have shown an association between biliary tract stones in patients with choledochal cysts and pancreatitis, and stone impaction within the pancreaticobiliary junction may cause pancreatitis (Fig. 46.6). An alternative mechanism for pancreatitis is bile reflux into the pancreatic duct (Okada et al, 1983; Swisher et al, 1994); although the anatomy of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system is conducive to bile reflux, little evidence is available to support this theory. Some patients with bile duct cysts and pancreatitis have normal pancreaticobiliary anatomy (Swisher et al, 1994), and some patients with choledochoceles also may have recurrent acute pancreatitis (Martin et al, 1992; Masetti et al, 1996). Thus pancreatitis associated with bile duct cysts has multiple potential causes.

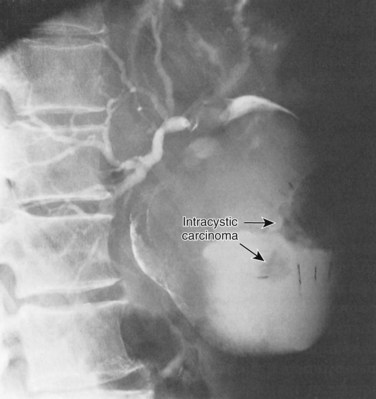

A significant association between bile duct cysts and hepatobiliary malignancy is well established (Dayton et al, 1983; Fieber & Nance, 1997; Flanigan, 1977; Komi et al, 1989; Rossi et al, 1987; Todani et al, 1979; Tsuchiya et al, 1977). The incidence of cancer associated with bile duct cysts ranges between 2.5% and 28% (Fieber & Nance, 1997; Flanigan, 1975; Ono et al, 1982). Hepatobiliary malignancies arising within or associated with bile duct cysts have included cholangiocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma, adenocanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma, bile duct sarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma (Fieber & Nance, 1997; Ono et al, 1982; Todani et al, 1979, 1987; Tsuchiya et al, 1977). Cholangiocarcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with bile duct cysts (see Chapter 50A, Chapter 50B, Chapter 50C, Chapter 50D ), and its incidence is approximately 20 times greater than the incidence of bile duct carcinoma in the general population (Flanigan, 1975). The incidence of cyst-associated malignancy is age related, increasing from 0.7% in the first decade of life to more than 14% after age 20 years (Voyles et al, 1983). The mean age of patients with cancer associated with bile duct cysts is 32 years (Ono et al, 1982). These findings underscore the necessity for a high index of suspicion of carcinoma in adults with biliary cystic disease.

Malignancies associated with bile duct cysts may arise within the cyst or elsewhere within the liver or pancreaticobiliary tract. Indeed, only 57% of tumors are intracystic (Fig. 46.7) (Flanigan, 1977), and they may occur after cyst excision (Ishibashi et al, 1997; Nagorney et al, 1984b). Malignancies may be associated with any type of bile duct cyst, although the prevalence of cancer is significantly greater in type I and IV cysts. Caroli disease (type V) is also associated with an increased incidence of carcinoma (Dayton et al, 1983).

The etiology of cyst-associated malignancies is unknown. Bile stagnation with the development of intrabiliary carcinogens leading to epithelial malignant degeneration is postulated as the most likely mechanism (Flanigan, 1977; Todani et al, 1979). Unconjugated deoxycholate and lithocholate have been associated with biliary metaplasia and mutagenicity, which may lead to neoplasia. Secondary bile acids have been found in bile duct cysts with cancer (Reveille et al, 1990), although neither their relative or absolute concentration in patients with bile duct cysts has differed in the presence or absence of cancer (Chijiiwa et al, 1993), thus suggesting other factors as primary carcinogens. An association between cystolithiasis and malignancy has not been established, although stasis and bacterial overgrowth associated with stones may lead to secondary bile acid formation. Long-term survival of patients with bile duct cysts and malignancy is rare. Delayed diagnosis, advanced stage of disease, intraabdominal seeding from previous operations, and tumor multicentricity generally preclude curative resection. Whether primary prophylactic excision of cysts in childhood can reduce the incidence of malignancy is unknown (Ono et al, 1982; Voyles et al, 1983).

Rare hepatobiliary problems arising in adults with common duct cysts include intrahepatic abscess and portal hypertension. Both conditions usually result from recurrent cholangitis and biliary obstruction after strictures of prior cystenterostomies. Large solitary hepatic abscesses represent an end stage of obstructive cholangitis and are usually completely obstructed, pus-filled intrahepatic cysts (see Chapters 43 and 66). These intrahepatic abscesses occur predominantly in the left intrahepatic duct (Mercadier et al, 1984; Ramond et al, 1984) and may be related partly to angulation of the left main duct. Adjacent liver parenchyma is fibrotic and atrophic and may harbor miliary abscesses within the peripheral bile duct radicles.

Portal hypertension associated with choledochal cysts may be due to secondary biliary cirrhosis or fibrosis, portal vein thrombosis, or Caroli disease with congenital hepatic fibrosis (see Chapter 70A; Kim, 1981; Martin & Rowe, 1979; Ono et al, 1982). Portal hypertension in adults generally is preceded by numerous operations for cyst drainage (Chaudhary et al, 1997; Hewitt et al, 1995; Lipsett et al, 1994). Portal hypertension in patients with bile duct cysts is manifested clinically by hepatosplenomegaly, hematemesis, melena, or ascites. Portal hypertension causes a hypervascularity of the hepatoduodenal ligament with prominent pericholedochal varices. Hepatic functional reserve deteriorates progressively, and hepatic coma and renal failure may be precipitated by recurrent cholangitis.

Treatment

General Principles

The definitive treatment of bile duct cysts is surgical (Todani et al, 1978). The therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of each type of bile duct cyst are shown in Fig. 46.8. In general, all bile duct cysts should be excised and bile flow reestablished by mucosa-to-mucosa bilioenteric anastomosis (see Chapter 29). If complete excision is not feasible, partial cyst excision and Roux-en-Y cystojejunostomy to an epithelial-lined portion of the cyst remnant is preferred; external drainage alone has no role in the management of bile duct cysts. Cholangioscopy can be used in adults to exclude retained ductal stones and ductal malignancy (see Chapter 21). Finally, long-term follow-up must be maintained in adults because of the age-related risk of malignancy and the frequency of late anastomotic strictures in patients treated without cyst resection.

Type I Cyst

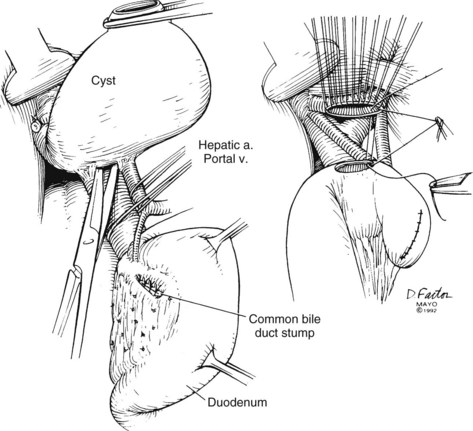

The treatment of choice for type I choledochal cysts in adults is total cystectomy and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Cyst excision eliminates the primary site of bile stasis and permits a bilioenteric anastomosis of normal jejunum and epithelial-lined proximal bile duct. The theoretical advantages of this approach include a reduced incidence of anastomotic stricture, stone formation, cholangitis, and intracystic malignancy. The advantages of a mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis have been extrapolated from similar biliary reconstructions for other biliary tract problems: benign strictures, common bile duct stones, and suppurative cholangitis (see Chapter 42A).

Reduction in risk of malignancy is based on three presumptions: 1) the potential carcinogenic effect of pancreatic secretions is eliminated because of total diversion from the biliary tract; 2) the production of mutagenic secondary bile acids are reduced because bacterial overgrowth in the bile is less frequent; and 3) abnormal cyst epithelium is excised. The clinical results of cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy have been excellent. Morbidity and mortality rates of excision have not been greater than that of drainage by Roux-en-Y choledochocystojejunostomy (Flanigan, 1975; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983; Stain et al, 1995; Todani et al, 1978). Moreover, most reports with late follow-up have confirmed that the majority of patients remain asymptomatic following excision (Chen et al, 1996; Chijiiwa et al, 1993; Gigot et al, 1996; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983; Uno et al, 1996), although recurrent cholangitis from anastomotic strictures occurs in 10% to 25% of patients (Chijiiwa & Tanaka, 1994; Gigot et al, 1996; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983; Uno et al, 1996).

Although reduction of malignancy by cyst excision has been suggested (Todani et al, 1987), cancer has developed after cyst excision (Nagorney et al, 1984a; Yamamoto et al, 1996). Previous cystenterostomy predisposes to ongoing risk of malignancy, and although such procedures are inadequate therapy for biliary cystic disease, they do not preclude definitive cyst excision (Gigot et al, 1996; Ono et al, 1982; Todani et al, 1988). Although morbidity is increased, low mortality rates and excellent long-term functional results can be achieved in adults with previous cystenterostomy, and reoperation and cyst excision should generally be undertaken. Bilioenteric continuity can be reestablished by hepaticoduodenostomy after cyst excision, although this method has been used infrequently in adults (Todani et al, 1981). An advantage of hepaticoduodenostomy is that the residual biliary epithelium is partially accessible to direct visualization by endoscopy (Todani et al, 1988). Technical factors influencing choice of hepaticoenterostomy (Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy vs. hepaticoduodenostomy) include aberrant hilar ductal anatomy, ductal strictures, ductal size, and hilar arterial anatomy (Todani et al, 1998). Mobility of the duodenum is an important factor and may limit its use in some patients.

Cyst excision in adults differs technically from the approach generally advocated for pediatric patients (Altman, 1994; Lilly, 1979). Most adults have had prior cyst drainage procedures, which may result in dense subhepatic adhesions. Recurrent cholangitis may result in epithelial degeneration or ulceration that can obscure or mimic malignancy, and regenerative epithelium may be densely adherent to the cyst wall. Although the vascularity of the pericholedochal tissue may increase, hypervascularity is most often limited to the ductal wall. In contrast to reports in pediatric patients (Lilly, 1979), complete dissection of the intracystic epithelium from the posterior cyst wall after excision of the anterior wall may be difficult. Because of the age-related incidence of cancer and its often occult operative and radiographic manifestations, total cyst excision to remove all intracystic epithelium is essential in adults. Only extensive hypervascularity from portal vein thrombosis or secondary biliary cirrhosis with portal hypertension would preclude excision.

Technically, cyst excision in adults can be accomplished by initially mobilizing the gallbladder from its bed to dissect the cyst away from the hilar structures. The portal vein is identified. Isolation and proximal control of the hepatic artery before dissection of the posterior cyst wall can be very helpful, especially if hypervascularity and dense adhesions are encountered. Before division of the cyst, the distal cyst is dissected from the pancreas to identify the pancreaticobiliary ductal junction (Ando et al, 1996). The intrapancreatic portion of the cyst is separated from the pancreas along the loose areolar plane between these structures. Meticulous fine suture ligature of collateral vessels will prevent potentially troublesome postoperative hemorrhage. Knowledge of the anatomy by preoperative cholangiography becomes particularly important to avoid damage to the pancreatic ducts. The cyst is transected distally within the head of the pancreas, and the distal bile duct is ligated carefully to prevent narrowing of the pancreatic duct. The cyst is mobilized proximally to the ductal confluence. After confirmation of the ductal confluence, the proximal cyst is transected, and the cyst is removed. Bilioenteric flow is reestablished through a wide mucosa-to-mucosa Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy at the level of the hilum (Fig. 46.9) or with a hepaticoduodenostomy. If a previous cystenterostomy has been performed, the same technique is used for excision after the cystenterostomy has been divided. An existing Roux loop can be reused for the new anastomosis. Hepatic arteries should be positioned posterior to the cystenterostomy to reduce potential injury in case of reoperation.

Portal hypertension secondary to biliary cirrhosis and inflammatory adhesions from severe pancreatitis or past drainage procedures may preclude cyst excision. In these circumstances, Roux-en-Y choledochocystojejunostomy is the preferred alternative treatment for type I choledochal cysts. Preoperative morbidity and mortality rates are similar to that of cyst excision. Adequate long-term functional results from Roux-en-Y cyst drainage can be expected in 60% to 70% of patients (Nagorney et al, 1984a; Ono et al, 1982; Rattner et al, 1983). Long-term results are improved by partial cyst excision in an effort to ensure a mucosa-mucosa bilioenteric anastomosis (Gigot et al, 1996). When either excision or Roux-en-Y drainage is performed, intraoperative choledochoscopy to exclude retained ductal stones and to biopsy the abnormal epithelium to exclude malignancy is advised. In patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis and unresectable cysts, intracystic closure of the base of the cyst proximal to its junction to the pancreatic duct or concurrent transduodenal sphincteroplasty should be used to prevent further episodes of pancreatitis (Rattner et al, 1983; Nagorney et al, 1984a). Careful long-term follow-up is essential because of the late development of malignancies, recurrent ductal stones, and anastomotic stricture (Chijiiwa & Tanaka, 1994; Fieber & Nance, 1997; Todani et al, 1998; Uno et al, 1996).

Portal decompression may be required before biliary reconstruction in patients who develop portal hypertension (Nagorney et al, 1984a). Preoperative assessment of these patients should include hepatic arteriography and portography. In general, central splenorenal shunts are preferred because portal decompression can be performed in an area distant from the subhepatic pericystic inflammation. In general, drainage is undertaken 6 to 12 weeks after portosystemic shunting. Alternatively, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stenting (TIPS) could be used for preoperative portal decompression (see Chapter 76E).

Type II Cyst

The treatment of choice for type II bile duct cysts is excision (Flanigan, 1975; Powell et al, 1981). Due to the low incidence, however, experience is limited, although reported results after excision have been excellent (Kouraklis et al, 1996; Lopez et al, 1991; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Powell et al, 1981). Technically, excision of type II bile duct cysts is similar to that of cholecystectomy. Depending on the size of the neck of the cyst at its junction with the common duct, the neck can either be closed primarily, or closure can be achieved via T-tube decompression of the common duct. Excision with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy has also been successful but has no clinical advantage over excision alone (Benhidjeb et al, 1994).

Type III Cyst (Choledochocele)

Choledochoceles are true cysts of the distal bile duct protruding into the duodenum. Patients are seen with biliary colic, cholangitis, or pancreatitis (Masetti et al, 1996). Choledochoceles are typically small (≤2 cm), and a classification scheme for them has been proposed (Sarris & Tsang 1989). Until recently, transduodenal cyst excision with or without sphincterotomy was the treatment of choice (Flanigan, 1975; Powell et al, 1981; Venu et al, 1984), but endoscopic sphincterotomy and cyst unroofing have now become the preferred treatment (Ladas et al, 1995; Martin et al, 1992; Masetti et al, 1996). The excellent long-term results with endoscopic treatment coupled with the diagnostic advantage of ERCP in defining the terminal pancreatic biliary anatomy clearly favor the endoscopic approach. Although transduodenal excision eliminates the risk of malignancy, the fact that only three cases of carcinoma in choledochoceles have been documented confirms that the risk of cancer alone is sufficiently low to justify endoscopic treatment as an alternative to surgery (Masetti et al, 1996).

Damage to the major pancreatic duct is the major source of operative morbidity and mortality. Identification of the duct of Wirsung is paramount before transduodenal cyst excision or sphincteroplasty because of numerous pancreatic biliary ductal variations (Komi et al, 1989, 1992). The pancreatic duct of Wirsung may enter the posterior wall of the choledochocele, or it may enter normally into the duodenum at the inferior aspect of the major papilla adjacent to the choledochocele (Sarris & Tsang, 1989). Before cyst excision or sphincteroplasty, the pancreatic duct orifice must be identified at the papilla to avoid damage to the duct. If the major pancreatic duct empties normally into the duodenum, it should be left in situ and not transected during choledochocele excision. If the pancreatic duct enters into the posterior wall of the cyst, the distal common bile duct and the duct of Wirsung should be implanted separately into the duodenal mucosa after cyst excision (Powell et al, 1981).

Type IV Cyst

The treatment of choice for type IV bile duct cysts is excision of the extrahepatic cyst and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (Mercadier et al, 1984; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Todani et al, 1984a). The extrahepatic component of type IVA and IVB cysts is approached as a type I bile duct cyst. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy complete the treatment of type IVB cysts, which have a choledochocele component. Type IVA cysts require more selective management because of the wide range of problems associated with the intrahepatic component of these cysts (Ando et al, 1997; Chijiiwa & Tanaka, 1994; Nagorney et al, 1984a; Todani et al, 1984a; Uno et al, 1996). When type IVA cysts are not complicated by hilar or intrahepatic ductal strictures, intrahepatic stones, intrahepatic abscess, or malignancy, bilioenteric continuity should be restored by a wide Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy at the bile duct confluence (Todani et al, 1988, 1998). In addition, the hepaticojejunostomy must take into account anomalous ductal anatomy. In patients with stones sequestered within the intrahepatic cysts, refractory ductal strictures distal to the intrahepatic cysts, or intrahepatic abscess due to chronic cholangitis, the abnormal hepatic segment should be resected. Bile flow is restored by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, and lobar hepatic resection is usually required to eliminate the complicated unilobar intrahepatic cystic component. In addition to the hepaticojejunostomy at the hilus, Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy incorporating the segmental bile duct of the resected segment may further optimize intrahepatic bile drainage. In patients with type IVA cysts and an intrahepatic component involving both lobes of the liver or complicated by cirrhosis, transhepatic tubes can be added to the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for access to the biliary tree for diagnosis and treatment.

The results of the treatment of type IVA cysts have been reviewed by several centers (Gigot et al, 1996; Todani et al, 1998; Uno et al, 1996; Ando et al, 1997). Although treatment varies widely because of the spectrum of pathology associated with these cysts, the results of cyst drainage alone without excision of either the intrahepatic or extrahepatic cystic components were considered satisfactory or good in fewer than 50% of patients (Todani et al, 1984a). In contrast, 90% of patients who had excision of the extrahepatic component of the type IVA cyst had good results, whether or not the intrahepatic component was resected. Although these findings suggest that adequate treatment of the extrahepatic component in these patients may provide effective prophylaxis for progression of the problems associated with intrahepatic cystic disease, the results of some studies (Ando et al, 1997; Todani et al, 1998) emphasize the importance of addressing the presence of variant ductal anatomy and stenoses at the hilum. If intrahepatic ductal stenosis or aberrant ducts are not recognized and addressed during extrahepatic cyst excision, subsequent reoperation will often be necessary. Both membranous or bridgelike stenoses should be excised circumferentially to their base. The long-term results of the treatment of type IVB cysts in adults are similar to those of type I choledochal cysts. Although patients with type IVA cysts and portal hypertension may be approached by proximal splenorenal shunts before cyst drainage, liver transplantation may provide a more durable solution. Resection of intrahepatic cysts in cirrhotic patients is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality rates and is generally contraindicated.

Caroli Disease

The treatment of Caroli disease depends on the extent of the intrahepatic bile duct cysts and the presence of congenital hepatic fibrosis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, or carcinoma. Caroli disease in adults may present in a localized form, limited to one hepatic lobe or segment, or a diffuse form, involving the entire intrahepatic biliary tree (Fig. 46.10) (Barros et al, 1979; Dayton et al, 1983; Mercadier et al, 1984; Witlin et al, 1982). Most adults with Caroli disease have a unilobar fusiform dilation of the intrahepatic ducts, most commonly involving the left ductal system (Mercadier et al, 1984; Ramond et al, 1984). Hepatic resection, with or without Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy, remains the treatment of choice in patients with Caroli disease limited to one lobe of the liver without the presence of concurrent cirrhosis or hepatic fibrosis. Cyst removal by hepatic resection provides the simplest solution to the recurrent problems of cholangitis, stone formation, and intrahepatic cancer (Mercadier et al, 1984; Todani et al, 1984a). Resection is always preferable to drainage if the liver parenchyma surrounding the cyst is atrophic. Indeed, segmental fibrosis and atrophy from complications of the underlying cyst are irreparable with drainage, which mandates segmental resection. Morbidity and mortality associated with hepatic resection for localized Caroli disease have been minimal, and functional results have been good, although follow-up has been limited (Bockhorn et al, 2006; Mercadier et al, 1984; Ramond et al, 1984). Alternative approaches to localized intrahepatic Caroli disease have included external T-tube biliary decompression or internal drainage via choledochoduodenostomy, Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. These alternatives are often ineffective because ductal drainage is distal to the intrahepatic cysts (Witlin et al, 1982). In general, recurrent cholangitis, hepatic abscess formation, intrahepatic stone formation, and carcinoma eventually complicate these approaches. If resection in patients with localized Caroli disease is not feasible, Roux-en-Y intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy to the intrahepatic cyst is preferable (Mercadier et al, 1984).

The results of the treatment of Caroli disease involving both lobes of the liver, or associated with portal hypertension from congenital hepatic fibrosis or secondary biliary cirrhosis, remain poor (Barros et al, 1979; Dayton et al, 1983; Mercadier et al, 1984). Most patients with diffuse Caroli disease have chronic recurrent cholangitis and portal hypertension with variceal bleeding, and their deaths are secondary to liver failure or carcinoma. Long-term medical therapy including antibiotics, analgesics, and litholytic agents may improve symptoms, but it does not permanently eliminate them. In selected patients with diffuse intrahepatic Caroli disease but with dominant unilobar disease, extended hepatic resection has been advocated, although long-term benefit remains unproven (Mercadier et al, 1984). Long-term transhepatic decompression using bilobar silicone tubes has been successful in the management of recurrent cholangitis (Witlin et al, 1982); however, to date, the treatment of diffuse Caroli disease remains disappointing.

In light of the natural history of Caroli disease—cirrhosis, variceal bleeding, and liver failure—hepatic transplantation offers the best chance of success. Orthotopic liver transplantation has been successfully used for Caroli disease (see Chapter 97A; De Kerckhove et al, 2006; Habib et al, 2006; Scharschmidt, 1984). If the diagnosis of bilobar Caroli disease is made, nonoperative medical treatment should be used until the patient is considered a transplant candidate. Avoidance of numerous ineffective operative procedures will reduce the technical risk of transplantation.

Laparoscopic Advances In Surgical Management

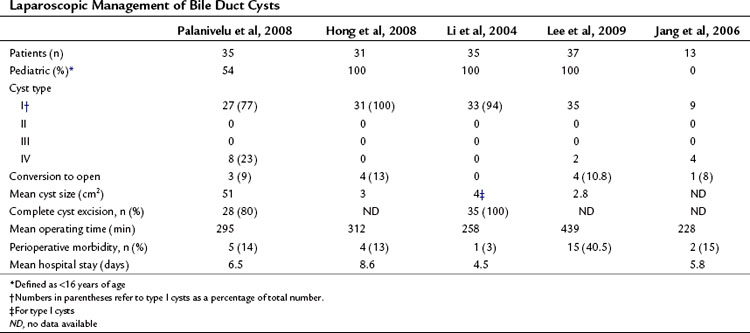

Minimally invasive approaches are increasingly used in most visceral procedures, and outcomes consistently suggest patient advantages over conventional approaches with regard to pain, wound complications, length of hospital stay, and recovery time. A laparoscopic approach in the management of bile duct cysts was first described in 1995 in a pediatric patient with a type I choledochal cyst (Farello et al, 1995), and several case reports and small series have been reported since (Abbas et al, 2006; Chokshi et al, 2009; Laje et al, 2007; Sun et al, 2009). Although feasibility has been demonstrated, the small numbers of patients in these reports has limited the assessment of outcomes, and comparisons with open procedures are needed. Only four contemporary series include more than 12 patients (Table 46.2), three of which included only pediatric cases. Palanivelu and colleagues (2008) recently reported the largest series to date of laparoscopic treatment of bile duct cysts. In this series of 35 patients, 16 were adults. Conversion to laparotomy was performed in three patients for suspicion of malignancy, and complete cyst excision was performed in 28; in five patients, an incomplete resection was performed as a result of extension of the cyst proximal to the hepatic duct confluence. Postoperative complications occurred in 14%, with no perioperative mortality.

Abbas HM, Yassin NA, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic resection of type I choledochal cyst in an adult and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy: a case report and literature review. Surg Laparoscop Endosc Percutaneous Tech. 2006;16(6):439-444.

Alonso-Lej F, Rever WB, Pessagno DJ. Congenital choledochal cysts, with a report of 2, and an analysis of 94 cases. Int Abstr Surg. 1959;108:1-30.

Altman RP. Choledochal cyst. In: Blumgart, LH, editor. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:1177.

Ando H, et al. Congenital stenosis of the intrahepatic bile duct associated with choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:426-430.

Ando H, et al. Complete excision of the intrapancreatic portion of choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:317-321.

Ando H, et al. Operative treatment of congenital stenoses of the intrahepatic bile ducts in patients with choledochal cysts. Am J Surg. 1997;173:491-494.

Ando H, et al. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst: a study of 13 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:23-25.

Babbitt DP. Congenital choledochal cysts: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Annal Radiol (Paris). 1969;12:231-240.

Barros JL, et al. Congenital cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Caroli’s disease): report of a case and review of the literature. Surgery. 1979;85:589-592.

Bass EM, Funston MR, Shaff MI. Caroli’s disease: an ultrasonic diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 1977;50:366.

Belli G, et al. Cystic dilatation of extrahepatic bile ducts in adulthood: diagnosis, surgical treatment and long-term results. HPB Surg. 1998;10:379-385.

Benhidjeb T, et al. Cystic dilatation of the common bile duct: surgical treatment and long-term results. Br J Surg. 1994;81:433-436.

Bockhorn M, et al. The role of surgery in Caroli’s disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(6):928-932.

Bruneton JN, et al. Congenital cysts of the liver in echography. J Radiol. 1983;64:471-476.

Calvo-Ponce JA, Reyes-Richa RV, Rodriguez Zentner HA. Cyst of the common hepatic duct: treatment and proposal for a modification of Todani’s classification. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7(1):80-82.

Caroli J, et al. La dilatation polykislique congenitale des voies biliaries intrahepatiques. Essai de classification. Semnares des Hopitaux de Paris. 1958;34:488-495.

Chaudhary A, Dhar P, Sachdev A. Reoperative surgery for choledochal cysts. Br J Surg. 1997;84:781-784.

Cheng SP, et al. Choledochal cyst in adults: aetiological considerations to intrahepatic involvement. Aust N Z J Surg. 2004;74(11):964-967.

Chen H-M, et al. Surgical treatment of choledochal cyst in adults. Results and long-term follow-up. Hepatogastroenterol. 1996;43:1492-1499.

Chijiiwa K, Koga A. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of patients with choledochal cysts. Am J Surg. 1993;165:238-242.

Chijiiwa K, et al. Are secondary bile acids in choledochal cysts important as risk factors in biliary tract carcinoma? Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63:109-112.

Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Late complications after excisional operation in patients with choledochal cyst. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:139-144.

Chokshi NK, et al. Laparoscopic choledochal cyst excision: lessons learned in our experience. J Laparoendoscopic Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(1):87-91.

Conway WC, et al. Type VI biliary cyst: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39(1):77-79.

Dayton MT, Longmire WP, Tompkins RK. Caroli’s disease: a premalignant condition? Am J Surg. 1983;145:41-48.

De Kerckhove L, et al. The place of liver transplantation in Caroli’s disease and syndrome. Transpl Int. 2006;19(5):381-388.

Deziel DJ, et al. Management of bile duct cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 1986;121:410-415.

Farello GA, et al. Congenital choledochal cyst: video-guided laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995;5(5):354-358.

Fieber SS, Nance FC. Choledochal cyst and neoplasm: a comprehensive review of 106 cases and presentation of two original cases. Am Surg. 1997;63:982-987.

Fitoz S, Erden A, Boruban S. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography of biliary system abnormalities in children. Clin Imaging. 2007;31(2):93-101.

Flanigan DP. Biliary cysts. Ann Surg. 1975;182:635-643.

Flanigan DP. Biliary carcinoma associated with biliary cysts. Cancer. 1977;40:880-883.

Funabiki T, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(1):159-169.

Gigot JF, et al. Bile duct cysts in adults: a changing spectrum of presentation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1996;3:405-411.

Grumbach R, Bourillon J, Auvert JP. Maladie fibrokystique du foie avec hypertension portale chez l’enfant: deux observations. Arch Anat Cytol Pathol. 1954;74:30.

Habib S, et al. Caroli’s disease and orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(3):416-421.

Hewitt PM, et al. Choledochal cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 1995;82:382-385.

Hoglund M, Muren C, Boijsen MW. Computed tomography with intravenous cholangiography contrast: a method of visualizing choledochal cysts. Eur J Radiol. 1990;10:159-161.

Hopkins NFG, et al. Complications of choledochal cysts in adulthood. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:229-235.

Horaguchi J, et al. Clinical study of choledochocele: is it a risk factor for biliary malignancies? J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(4):396-401.

Ishibashi T, et al. Malignant change in the biliary tract after excision of choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1687-1691.

Iwafuchi M, et al. Familial occurrence of congenital bile duct dilatation. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:353-355.

Iwai N, et al. Biliary manometry in choledochal cyst with abnormal choledochopancreatico ductal junction. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:873-876.

Jesudason SRB, et al. Choledochal cysts in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:410-413.

Jona JZ, et al. Anatomic observations and etiologic and surgical considerations in choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:315-320.

Joseph VT. Surgical techniques and long-term results in the treatment of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:782-787.

Kamisawa T, et al. Classification of choledochocele. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(61):29-32.

Kim OH, Chung HJ, Choi BG. Imaging of the choledochal cyst. Radiographics. 1995;15:69-88.

Kim SH. Choledochal cyst: survey by the surgical section of the American Academy of Pediatrics. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:402-407.

Komi N, Takehara H, Kunitomo K. Choledochal cyst: anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system and biliary malignancy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:63-74.

Komi N, et al. Does the type of anomalous arrangement of pancreaticobiliary ducts influence the surgery and prognosis of choledochal cyst? J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:728-731.

Kouraklis GR, et al. Cystic dilatations of the common bile duct in adults. HPB Surgery. 1996;10:91-95.

Kusunoki M, et al. Choledochal cysts: oligoganglionosis in the narrow portion of the choledochus. Arch Surg. 1988;123:984-986.

Ladas SD, et al. Choledochocele, an overlooked diagnosis: report of 15 cases and review of 56 published reports from 1984 to 1992. Endoscopy. 1995;27:233-239.

Laje P, Questa H, Bailez M. Laparoscopic leak-free technique for the treatment of choledochal cysts. J Laparoendoscop Adv Surg Techn A. 2007;17(4):519-521.

Lee KH, et al. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cysts in children: an intermediate-term report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;25(4):355-360.

Lilly JR. The surgical treatment of choledochal cyst. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149:36-42.

Lipsett PA, et al. Choledochal cyst disease: a changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:644-652.

Lopez RR, et al. Variation in management based on type of choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1991;161:612-615.

Martin LW, Rowe GA. Portal hypertension secondary to choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1979;190:638-639.

Martin RF, et al. Symptomatic choledochoceles in adults: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography recognition and management. Arch Surg. 1992;127:536-539.

Masetti R, et al. Choledochocele: changing trends in diagnosis and management. Surg Today. 1996;26:281-285.

Matsumoto Y, et al. Clinicopathologic classification of congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 1977;134:569-574.

Matsumoto Y, et al. Congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct as a cause of primary bile duct stone. Am J Surg. 1977;134:346-352.

Mercadier M, et al. Caroli’s disease. World J Surg. 1984;8:22-29.

Miyazaki T, et al. Single-shot MR cholangiopancreatography of neonates, infants, and young children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:33-37.

Morgan CL, et al. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of a type I choledochal cyst. Southern Med J. 1980;73:1389.

Musante F, Derchi LE, Bonati P. CT cholangiography in suspected Caroli’s disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982;6:482-485.

Nagata E, et al. Choledochal cyst: complications of anomalous connection between the choledochus and pancreatic duct and carcinoma of the biliary tract. World J Surg. 1986;10:102-110.

Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, Adson MA. Choledochal cysts in adults: clinical management. Surgery. 1984;96:656-663.

Nagorney DM, et al. Cystadenoma of the proximal common hepatic duct: the use of abdominal ultrasonography and transhepatic cholangiography in diagnosis. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1984;59:118-121.

Oguchi Y, et al. Histopathologic studies of congenital dilatation of the bile duct as related to an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system: clinical and experimental trials. Surgery. 1988;103:168-173.

Ohkawa H, et al. The production of anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in canine models. Z Kinderchirurg. 1981;32(4):328-336.

Okada A, et al. Common channel syndrome: diagnosis with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and surgical management. Surgery. 1983;93:634-642.

Okada A, et al. Congenital dilatation of the bile duct in 100 instances and its relationship with anomalous junction. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;171:291-298.

Olbourne NA. Choledochal cysts: a review of the cystic anomalies of the biliary tree. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1975;56:26-32.

Ono J, Sakoda K, Akita H. Surgical aspect of cystic dilatation of the bile duct: an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary tract in adults. Ann Surg. 1982;195:203-208.

Palanivelu C, et al. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cysts: technique and outcomes—a retrospective study of 35 patients from a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(6):839-846.

Park DH, et al. Can MRCP replace the diagnostic role of ERCP for patients with choledochal cysts? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(3):360-366.

Powell CS, Sawyers JL, Reynolds VH. Management of adult choledochal cysts. Ann Surg. 1981;193:666-676.

Ramond M-J, et al. Partial hepatectomy in the treatment of Caroli’s disease: report of a case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:367-370.

Rattner DW, Schapiro RH, Warshaw AL. Abnormalities of the pancreatic and biliary ducts in adult patients with choledochal cysts. Arch Surg. 1983;118:1068-1073.

Reveille RM, van Stiegmann G, Everson GT. Increased secondary bile acids in a choledochal cyst: possible role in biliary metaplasia and carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:525-527.

Rossi FL, et al. Carcinomas arising in cystic conditions of the bile ducts: a clinical and pathologic study. Ann Surg. 1987;205:377-384.

Sarris GE, Tsang D. Choledochocele: case report, literature review, and a proposed classification. Surgery. 1989;105:408-414.

Savader SJ, et al. Choledochal cysts: classification and cholangiographic appearance. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:327-331.

Savader SJ, et al. Choledochal cysts: role of noninvasive imaging, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, and percutaneous biliary drainage in diagnosis and treatment. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1991;2:379-385.

Saxena R, et al. Benign disease of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 1988;75:803-806.

Scharschmidt BF. Human liver transplantation: analysis of data on 540 patients from four centers. Hepatology. 1984;4:95S-101S.

Scudamore CH, et al. Surgical management of choledochal cysts. Am J Surg. 1994;1167:497-500.

Shaffer E. Can MRCP replace ERCP in the diagnosis of congenital bile-duct cysts? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(2):76-77.

Stain SC, et al. Choledochal cyst in the adult. Ann Surg. 1995;222:128-133.

Sty JR, et al. Hepatic scintigraphy in Caroli’s disease. Radiology. 1978;127:732.

Sun DQ, et al. Laparoscopic management of type I choledochal cyst in adults: cyst resection, assisted Roux-en-Y reconstruction and hepaticojejunostomy. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2009;18(1):1-5.

Swisher SG, et al. Pancreatitis associated with adult choledochal cysts. Pancreas. 1994;9:633-637.

Tan KC, Howard ER. Choledochal cyst: a 14-year surgical experience with 36 patients. Br J Surg. 1988;75:892-895.

Todani T, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: classifications, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263-269.

Todani T, et al. Management of congenital choledochal cyst with intrahepatic involvement. Ann Surg. 1978;187:272-280.

Todani T, et al. Carcinoma arising in the wall of congenital bile duct cysts. Cancer. 1979;44:1134-1141.

Todani T, et al. Hepaticoduodenostomy at the hepatic hilum after excision of choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1981;142:584-587.

Todani T, et al. Congenital choledochal cyst with intrahepatic involvement. Arch Surg. 1984;119:1038-1043.

Todani T, et al. Anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in patients with a choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1984;147:672-676.

Todani T, et al. Carcinoma related to choledochal cysts with internal drainage operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:61-64.

Todani T, et al. Reoperation for congenital choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1988;207:142-147.

Todani T, et al. Pseudopancreatitis in choledochal cyst in children: intraoperative study of amylase levels in the serum. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:303-306.

Todani T, et al. Co-existing biliary anomalies and anatomical variants in choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1998;85:760-763.

Tohma T, et al. Usefulness of computed tomography during cholangiography for the diagnosis of multiple hepatic peribiliary cysts: a report of three cases with chronic liver disease. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(3):372-375.

Tsuchiya R, et al. Malignant tumors in choledochal cysts. Ann Surg. 1977;186:22-28.

Uno K, et al. Development of intrahepatic cholelithiasis long after primary excision of choledochal cyst. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:583-588.

Venu RP, et al. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis and treatment of choledochocele. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1144-1149.

Voyles CR, et al. Carcinoma in choledochal cysts: age-related incidence. Arch Surg. 1983;118:986-988.

Wiedmeyer D, et al. Choledochal cyst: findings on cholangiopancreatography with emphasis on ectasia of the common channel. Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:969-972.

Witlin LT, et al. Transhepatic decompression of the biliary tree in Caroli’s disease. Surgery. 1982;91:205-209.

Yamaguchi M. Congenital choledochal cyst. Analysis of 1,433 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1980;140:653-657.

Yamamoto J, et al. Bile duct carcinoma arising from the anastomotic site of hepaticojejunostomy after the excision of congenital biliary dilatation: a case report. Surgery. 1996;119:476-479.

Young W, et al. Congenital biliary dilatation: a spectrum of disease detailed by ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:333-336.