CHAPTER 44 Benign tumours of the ovary

Introduction

Ovarian cysts are common, frequently asymptomatic and often resolve spontaneously. They are the fourth most prevalent gynaecological cause of hospital admission. By 65 years of age, 4% of all women in England and Wales will have been admitted to hospital for this reason. Ovarian cysts are found either during the course of investigation of abdominal pain or as a result of imaging for other reasons. It is important to distinguish between ovarian cysts that will require assessment and management and those that will resolve spontaneously. In addition, reliable prediction of their benign or malignant nature would be beneficial in order to arrange appropriate referral and management, as per Improving Outcome Guidance (NHS Executive 1999).

Physiological Ovarian Cysts

As pelvic ultrasound, particularly transvaginal scanning, is now used more frequently, physiological cysts are detected more often. The corpus luteum may persist and continue to secrete progesterone beyond its natural lifespan, and thus cause some menstrual irregularity, or haemorrhage may occur into the cyst at or just after ovulation. Most good radiologists will recognize the features of a follicle, corpus luteum or haemorrhagic cyst and will report these as such. Most simple cysts will resolve spontaneously over a period of 6 months (Zanetta et al 1996, Saasaki et al 1999). Occasionally, they can persist for longer or grow in size to become a clinical problem. Physiological cysts should simply be regarded as large versions of the cysts which form in the ovary during the normal cycle.

Failure of development of the lead follicle results in anovulation and is a classical finding in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is predominantly an endocrine abnormality, and polycystic ovaries do not cause abdominal pain (see Chapter 18, Polycystic ovary syndrome, for more information).

Clinical Presentation of Symptomatic Ovarian Cysts

Benign ovarian cysts present as follows:

Abdominal swelling, bloating and pressure effects

An attempt to assess symptoms qualitatively and quantitatively in order to distinguish women who may have an ovarian cyst from those unlikely to have a cyst suggests that recent-onset, severe and persistent symptoms should warrant further investigation (Bankhead et al 2008).

Investigation

Ultrasound

The techniques of transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound are discussed in detail in Chapter 6. Ultrasound is the single most important investigation and can demonstrate the presence of an ovarian mass with 81% sensitivity and 75% specificity. Most ovarian masses are cystic, whilst the presence of solid areas makes a malignancy more likely. Reporting of an ultrasound finding of an ovarian cyst has been standardized in order to allow for the allocation of a scoring system to assist in the preoperative assessment of the risk of any ovarian cyst being malignant. The ultrasound is awarded a U score of 0 if no cyst is present, 1 if only one characteristic is found, and 3 if two or more characteristics are found:

Ultrasound-guided diagnostic ovarian cyst aspiration

This investigation has been introduced gradually into gynaecological practice without the benefit of appropriate trials to indicate its potential efficacy. Unfortunately, this technique has a false-negative rate of up to 71% and a false-positive rate of 2% for the cytological diagnosis of malignancy (Diernaes et al 1987). The degree of risk of dissemination of malignant cells along the needle track or into the peritoneal cavity is not established. Most simple cysts will resolve, and most complex cysts require definitive management. Thus, due to its poor prognostic value and the potential for upstaging an early malignancy, cyst aspiration is not recommended for the assessment or management of ovarian cysts.

Management

Simple cysts less than 8 cm in diameter with normal CA125 levels

A normal follicular cyst up to 3 cm in diameter requires no further investigation. A simple cyst which is unilocular, echo-free without solid parts or papillary formations less than 8 cm in diamater with a normal CA125 level should have a repeat ultrasound in 3–6 months. If the cyst persists or grows, laparoscopic removal is advised. Premenopausal women under 40 years of age are more likely to want the option of further children and less likely to have a malignant epithelial tumour. In a study by Ekerhovd et al (2001), only three (0.73%) of 413 premenopausal women who underwent surgery for simple echo-free cysts without solid parts or papillary formations had borderline (n = 2) or malignant (n = 1) tumours.

The use of a combined oral contraceptive is unlikely to accelerate the resolution of a functional cyst (Steinkampf and Hammond 1990). Hormonal treatment of endometriosis does not usually benefit an endometrioma, the mainstay management of which is surgical.

The older woman

Women over 50 years of age are far more likely to have a malignancy and have less to gain from the conservative management of a pelvic mass. However, the capacity of the postmenopausal ovary to generate benign cysts is greater than previously thought, occurring in up to 17% of asymptomatic women (Levine et al 1992). Over 50% of simple cysts will resolve spontaneously and almost 30% will remain static (Levine et al 1992, Bailey et al 1998, Saasaki et al 1999).

Considerable efforts have been made to safely avoid unnecessary surgery in this older age group. However, one group found malignant tumours in 8.9% of 112 postmenopausal women with monolocular simple cysts studied between 1987 and 1993 with transvaginal ultrasound (Osmers et al 1998). They did not find internal echoes helpful in identifying malignancies. They found malignancies in 4.6% of cysts less than 40 mm in diameter, 10.8% of cysts 40–69 mm in diameter, and 18.2% of cysts more than 69 mm in diameter. Their view was that only cysts less than 3 cm in diameter could be managed conservatively. The results of other studies are more reassuring. In particular, a more recent study running from 1992 to 1997 found that only 1.6% of 247 echo-free cysts in postmenopausal women were malignant and that all of these were more than 7.9 cm in diameter (Ekerhovd et al 2001). It was only cysts with small solid areas or papillary formations on the internal side of the cyst wall or echogenic cyst content that carried a 10% risk of malignancy in the 130 cysts studied. Of the nine invasive cancers detected in this group, five were in cysts less than 8 cm in diameter.

This suggests that simple, echo-free, unilateral cysts without solid parts or papillary formations and less than 8 cm in diameter are very likely to be benign, and may safely be managed conservatively with 3–6-monthly ultrasound and CA125 estimation (Goldstein 1993, Ekerhovd et al 2001).

All other cysts

Echo-free ovarian cysts more than 7.9 cm in diameter are unlikely to be physiological or to resolve spontaneously, and will be malignant in approximately 5% of premenopausal women and approximately 15% of postmenopausal women (Ekerhovd et al 2001). These are probably better removed or, at the very least, rescanned 3 months later if the woman is unwilling to undergo surgery.

The pregnant patient

Pathology (Box 44.1)

Physiological ovarian cysts

Simple follicular cyst

Histologically, follicular cysts show a lining of variably luteinized granulosa cells.

Corpus luteum cyst

Macroscopic identification is straightforward due to the intense yellowish colour resulting from mature luteinized theca cells (Figure 44.1).

Massive oedema

Ninety per cent of all ovarian tumours are benign, although this varies with age, and they can arise from any tissue in the ovary. Approximately one in eight ovarian tumours in patients under 45 years of age is malignant; by contrast, the proportion is one in three in older women (Scully et al 2004). Most benign ovarian tumours are cystic, and the finding of solid elements makes malignancy more likely. However, fibromata, thecomata, dermoids and some transitional cell tumours are totally benign despite being partly or predominantly solid.

Pathological ovarian cysts

The diagnosis of ovarian tumours ultimately depends upon histological examination.

Benign germ cell tumours

Germ cell tumours account for approximately 30% of all ovarian tumours (Young et al 2004). Ninety five per cent of germ cell tumours are dermoid cysts (mature cystic teratomas) and most of the remainder are malignant. Malignant tumours are usually solid, although benign forms also commonly have a solid element. As the name suggests, they arise from totipotential germ cells, and may therefore contain elements of all three germ layers. Most malignant germ cell tumours are composed of primitive or immature elements.

Dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma)

Mature cystic teratoma accounts for 27–44% of all ovarian tumours and up to 58% of benign tumours (Koonings et al 1989).

Macroscopically, dermoid cysts appear as ovoid tumours, commonly multilocular, with diameters ranging from 0.5 to 40 cm (average 15 cm) with a smooth external surface and filled with sebaceous and hairy material. Not uncommonly, a nodule composed of teeth or bone (Rokitansky protuberance) is found. This area is known to harbour the greatest variety of tissue types, and therefore histological examination is recommended, even when decalcification is required (Rosai 2004).

Benign epithelial tumours

Benign serous tumours

Serous cystadenomas are the most common type of benign epithelial tumour. Approximately 10% are bilateral. They can occasionally attain huge dimensions (Figure 44.2) and can be uni- or multilocular. Characteristically, the cysts are thin walled and feature watery contents. The cysts may have a smooth lining, but not uncommonly polypoid excrescences can be seen.

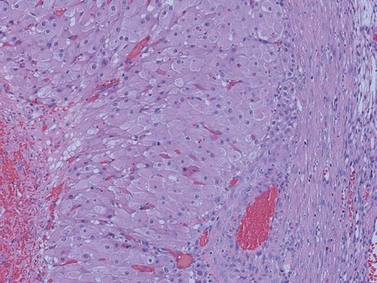

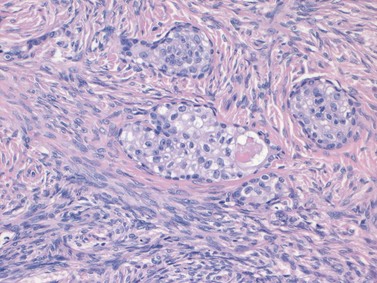

Transitional cell (Brenner) tumours

The tumour consists of nests and islands of transitional-type epithelial cells with characteristically grooved nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm set in a dense fibrotic stroma, giving a largely solid appearance. The nests show central lumina containing mucin and may be lined by columnar cells with a mucinous or ciliated appearance (Figure 44.3).

Benign sex cord stromal tumours

Oestrogen-secreting tumours

Thecoma–fibroma group of tumours

Signet ring stromal tumour

KEY POINTS

Bailey CL, Ueland FR, Land GL, et al. The malignant potential of small cystic ovarian tumors in women over 50 years of age. Gynecological Oncology. 1998;69:3-7.

Bankhead CR, Collins C, Stokes-Lampard H, et al. Identifying symptoms of ovarian cancer: a qualitative study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115:1008-1014.

Diernaes E, Rasmussen J, Soersen T, Hasche E. Ovarian cysts: management by puncture? Lancet. 1987;i:1084.

Ekerhovd E, Wienerroith H, Staudach A, Granberg S. Preoperative assessment of unilocular adnexal cysts by transvaginal ultrasonography: a comparison between ultrasonographic morphological imaging and histopathologic diagnosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184:48-54.

Goldstein SR. Conservative management of small postmenopausal cystic masses. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1993;36:395-401.

Koonings PP, Campbell K, Mishell DRJr, Grimes DA. Relative frequency of primary ovarian neoplasms: a 10 year review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;74:921-926.

Levine D, Gosink B, Wolf SI, Feldesman MR, Pretorius DH. Simple adnexal cysts: the natural history in postmenopausal women. Radiology. 1992;184:653-659.

NHS Executive. Guidance on Commissioning Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Gynaecological Cancers. No. 16149. Department of Health, 1999.

Osmers RGW, Osmers M, von Maydell B, Wagner B, Kuhn W. Evaluation of ovarian tumors in postmenopausal women by transvaginal sonography. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1998;77:81-88.

Rosai J. Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology, 9th edn. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. Chapter 19

Russell P, Robboy S, Anderson MC. Sex cord-stromal and steroid cell tumours of the ovaries. In: Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. London: Harcourt Publishers Ltd; 2002. Chapter 21

Saasaki H, Oda M, Ohmura M, et al. Follow up of women with simple ovarian cysts detected by transvaginal sonography in the Tokyo metropolitan area. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:415-420.

Scully RE, Clement PB, Young RH. Ovarian surface epithelial-stromal tumours. Sternberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2004. Chapter 44

Spencer CP, Robarts PJ. Management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2006;8:14-19.

Steinkampf MP, Hammond KR. Hormonal treatment of functional ovarian cysts: a randomised, prospective study. Fertility and Sterility. 1990;54:775-777.

Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. Chapter 2

Young RH, Scully RE. Non neoplastic disorders of the ovary. In: Haines and Taylor’s Gynaecological Pathology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. Chapter 17

Young RH, Clement PB, Scully RE. Sex cord stromal, steroid cell and germ cell tumours of the ovary. Sternberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2004. Chapter 55

Zanetta G, Lissoni A, Torri V, et al. Role of puncture and aspiration in expectant management of simple ovarian cysts: a randomised study. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:1110-1113.