Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis

Benign acanthomas

Seborrheic keratoses

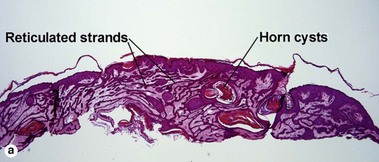

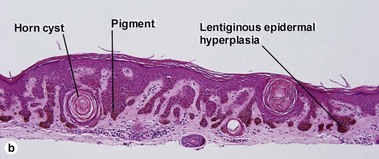

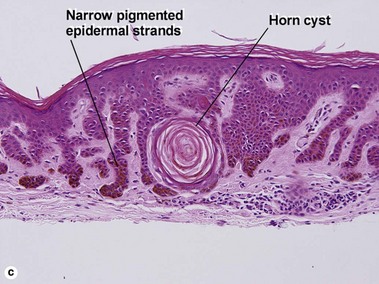

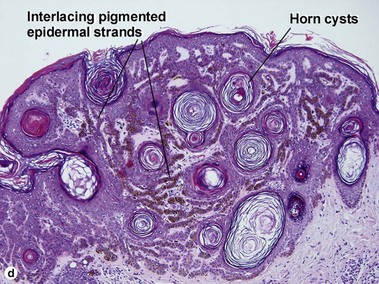

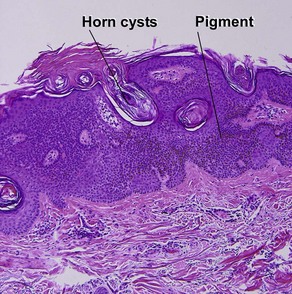

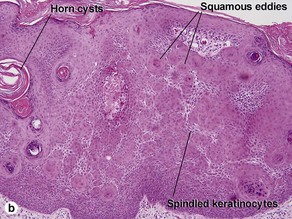

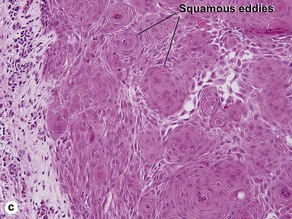

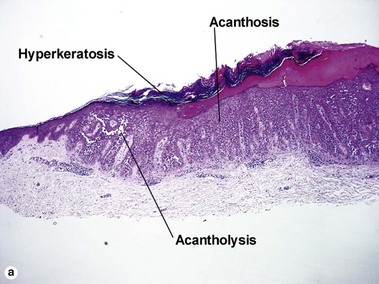

Acanthotic seborrheic keratosis

Acanthotic seborrheic keratoses are composed of broad sheets of cells with intervening horn cysts or pseudohorn cysts. Horn cysts are completely encased within the acanthoma, whereas pseudohorn cysts open to the surface. Like other seborrheic keratoses, they may become irritated or inflamed.

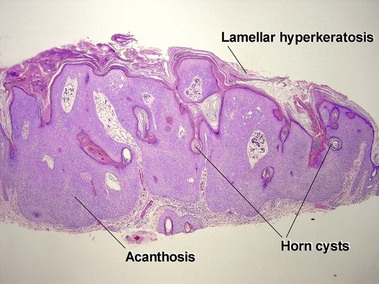

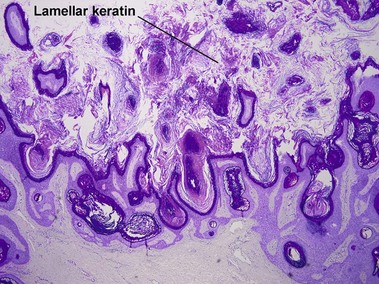

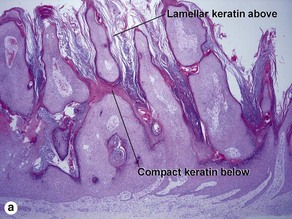

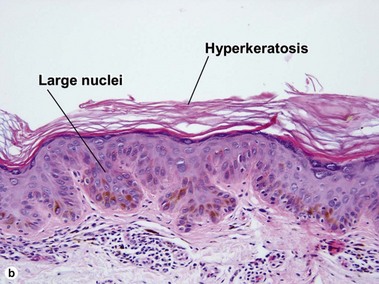

Hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratosis

The tall stacked stratum corneum is typically much thicker than the epidermis. As in other forms of seborrheic keratosis, the keratin has a loose lamellar “shredded-wheat” appearance unless the lesion has become irritated or inflamed. Papillomatosis is characteristic, but variable in degree. Horn cysts are inconspicuous or absent.

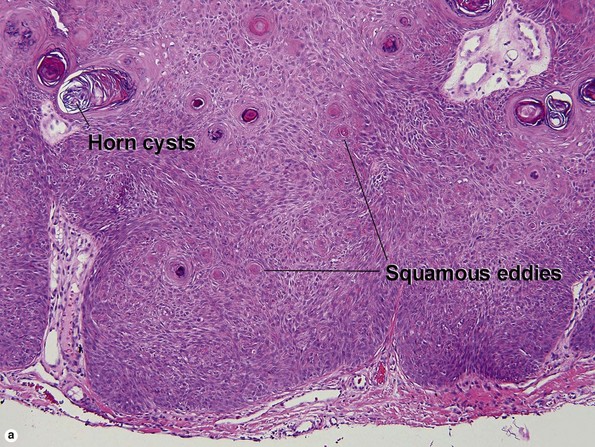

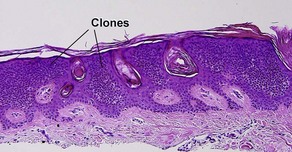

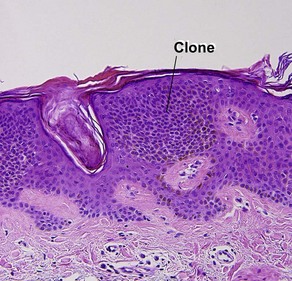

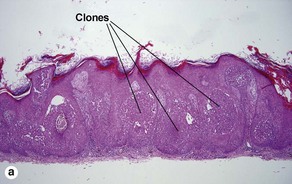

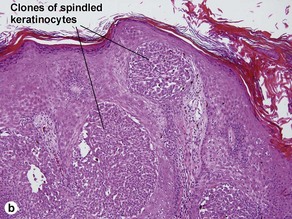

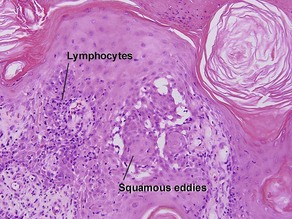

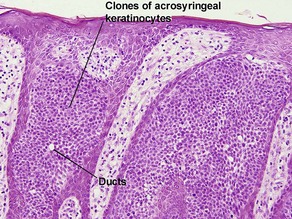

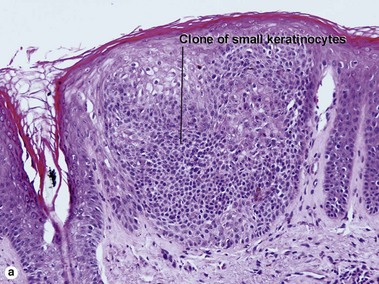

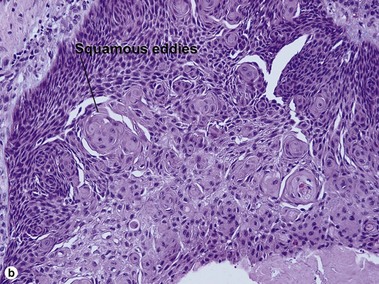

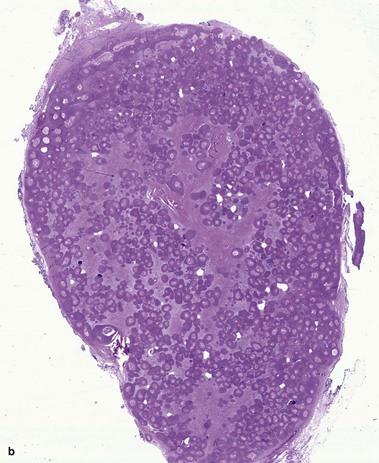

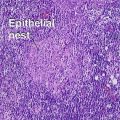

Clonal seborrheic keratosis

Clonal seborrheic keratosis is characterized by islands of small keratinocytes with uniform bland nuclei. The nests are embedded within the epidermis. Sometimes, the nests are large enough that the normal epidermis is reduced to thin strands separating the large nests. Horn cysts are usually absent. The nests may demonstrate pigment. There may be squamous eddies (irritated seborrheic keratosis), lymphocytes (inflamed seborrheic keratosis), or both. In contrast to Bowen’s disease, the cells are uniform and atypia is absent. In contrast to hidroacanthoma simplex, no ducts are present within the clones.

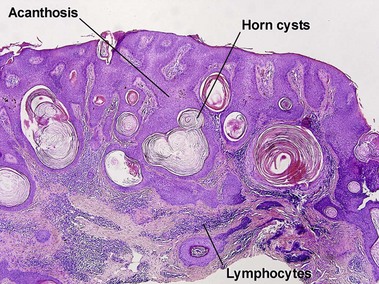

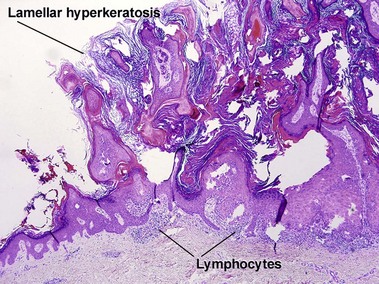

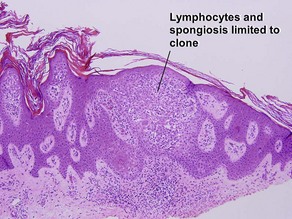

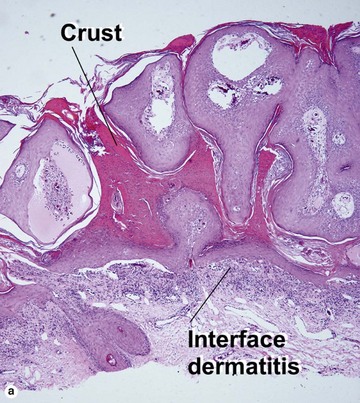

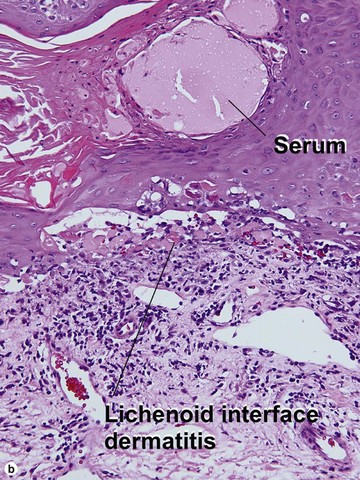

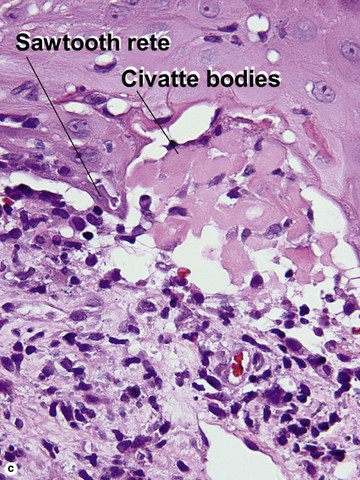

Inflamed seborrheic keratosis

Inflamed seborrheic keratosis is characterized by lymphocytes and spongiosis within the epidermis or the presence of lichenoid interface dermatitis. Some areas of the tumor typically still produce a loose lamellar “shredded-wheat” pattern of keratin, and horn cysts composed of loose lamellar keratin are often present. As in irritated seborrheic keratoses, a zone of loose lamellar keratin may sometimes be seen above a zone of dense eosinophilic keratin. When clonal, the spongiosis and lymphoid infiltrate are typically restricted to the clonal islands.

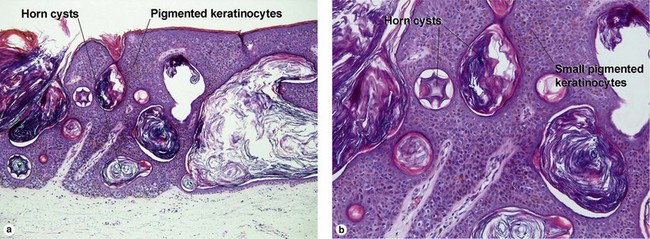

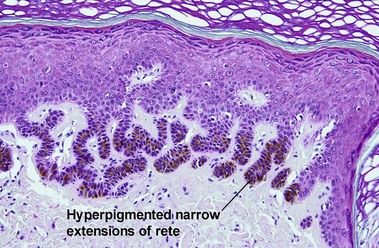

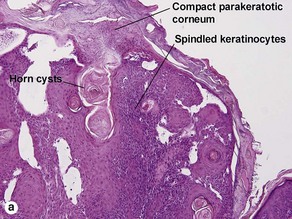

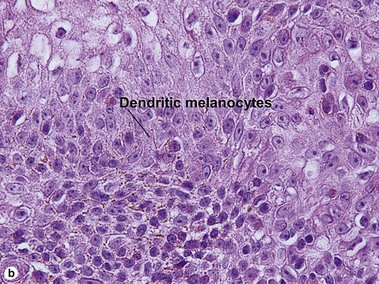

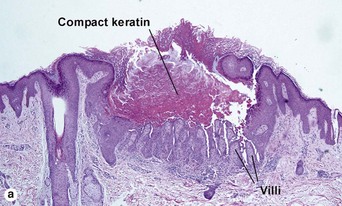

Melanoacanthoma

Cutaneous melanoacanthomas are a type of seborrheic keratosis, composed of both small cuboidal keratinocytes and pigmented dendritic melanocytes. Most melanin pigment is contained within the melanocytic dendrites with little visible pigment within the keratinocytes. Unlike most seborrheic keratoses, horn cysts and loose lamellar horn are typically absent. Instead, the overlying stratum corneum is almost always compact, eosinophilic, and parakeratotic. Cutaneous melanoacanthomas may be clonal. Oral melanoacanthomas are reactive proliferations unrelated to seborrheic keratosis.

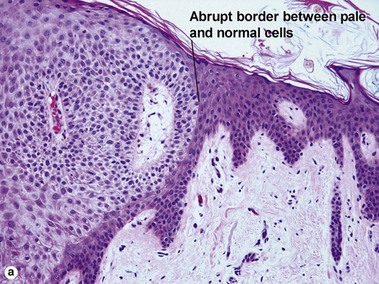

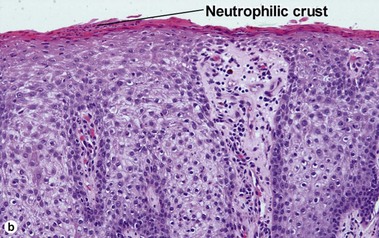

Clear cell acanthoma (pale cell acanthoma)

Clear cell acanthomas are recognizable as a clearly defined acanthotic area of the epidermis with ample clear or pale cytoplasm. A thin overlying parakeratotic scale crust is present, and there is a distinct transition between surrounding normal stratum corneum and the parakeratotic stratum corneum as well as between the normal epidermis and the paler cells comprising the acanthoma. Neutrophils are scattered throughout the lesion. The cells of the acanthoma are deficient in phosphorylase, resulting in an accumulation of glycogen.

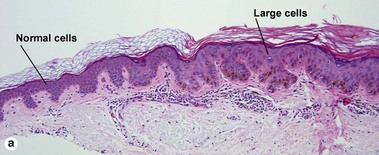

Large cell acanthoma

The rete ridges may be bulbous or there may be a solid plate-like acanthosis. The cells composing the acanthoma have large nuclei, typically twice the size of the nuclei in the surrounding epidermis.

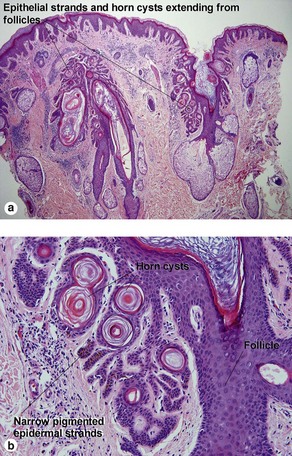

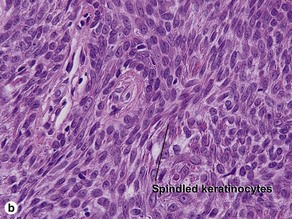

Inverted follicular keratosis (IFK)

The outline of the epithelial column is smooth, with no evidence of jagged invasive growth.

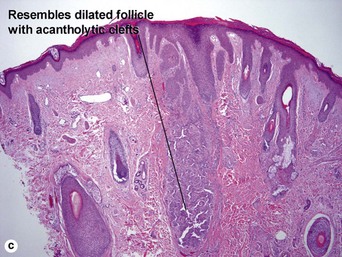

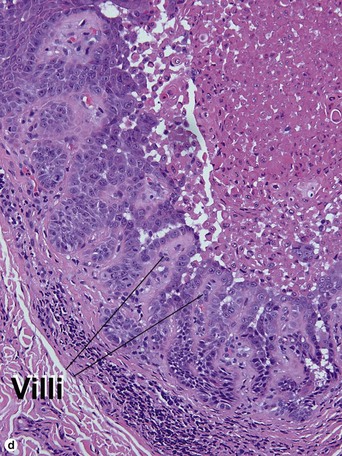

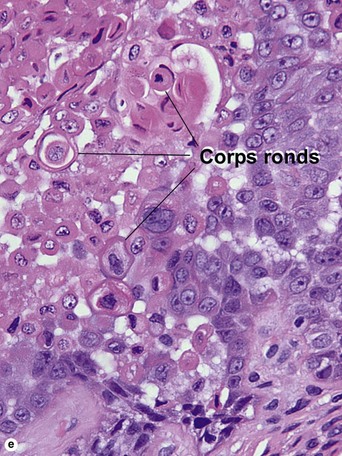

Warty dyskeratoma

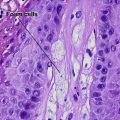

Two types of dyskeratotic cells are noted. Corps ronds are round dyskeratotic cells that stain pale pink to red, and may have a wide clear halo surrounding the nucleus. Grains are flattened basophilic dyskeratotic cells. Either or both may be present. Some lesions are crateriform; others resemble expanded hair follicles.

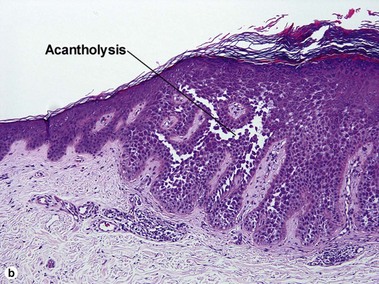

Acantholytic acanthoma

The appearance resembles the “dilapidated brick wall” of Hailey–Hailey disease.

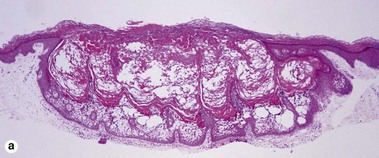

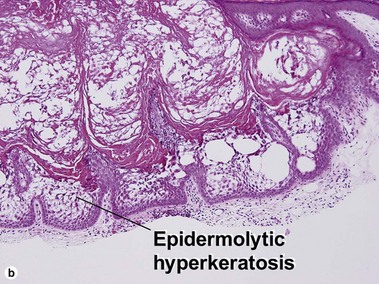

Epidermolytic acanthoma

Epidermolytic acanthomas are characterized by epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. The granular layer is thick and contains irregularly shaped keratohyalin granules and cytoplasmic borders are indistinct. Clinically, the lesions are solitary discrete acanthomas resembling seborrheic keratoses.

Epidermal nevi

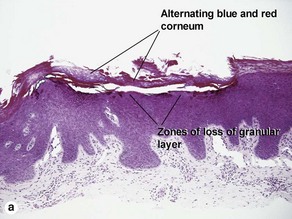

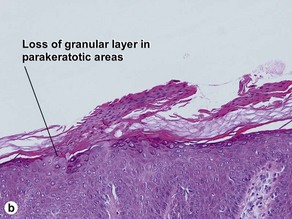

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN)

The name “inflammatory” linear verrucous epidermal nevus relates to the erythematous clinical appearance of the lesions. Orthokeratosis and parakeratosis alternate from right to left.

Widely separated lesions involving different parts of the body suggest that the mutation occurred in the embryo prior to gastrulation. In this case, the affected cell line is more likely to contribute to many organ tissues, including the gonads.

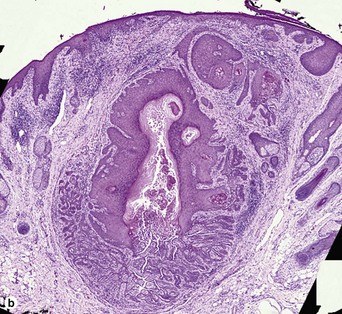

Cysts

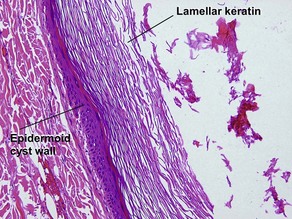

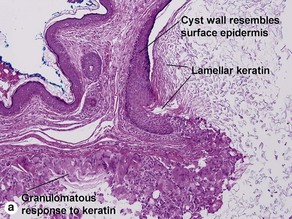

Epidermoid cyst (epidermal inclusion cyst, infundibular cyst)

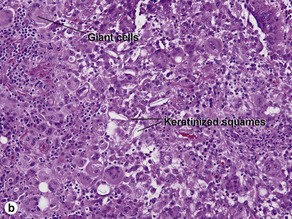

Epidermoid cysts often connect to the surface with a visible punctum. This connection may be visible histologically. In a young cyst, a rete ridge pattern may be present. As tension increases within the cyst, the lining is stretched and the rete pattern disappears. Ruptured cysts demonstrate a neutrophilic infiltrate, histiocytes, and foreign-body giant cells. Flat bits of keratin are noted within giant cells.

Vellus hair cyst

Eruptive vellus hair cysts may coexist with steatocystomas, and individual cysts may have features of both. Eruptive vellus hair cysts have been reported in association with renal failure and Lowe syndrome (Fanconi-type renal failure, mental retardation, and eye abnormalities).

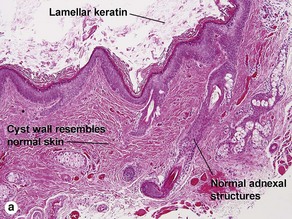

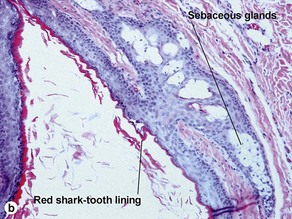

Dermoid cyst

Adnexal structures within the cyst wall may include terminal hair follicles, sebaceous glands, eccrine glands, and apocrine glands. Terminal hair shafts are commonly noted within the cyst contents. Lamellar keratin is typically present, although some dermoid cysts demonstrate a bright red “shark-tooth” lining similar to that of a steatocystoma. Dermoid cysts occur in embryonic fusion planes and may be associated with underlying skull defects.

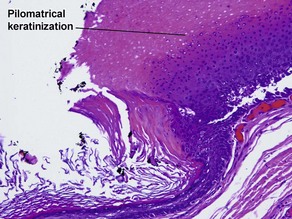

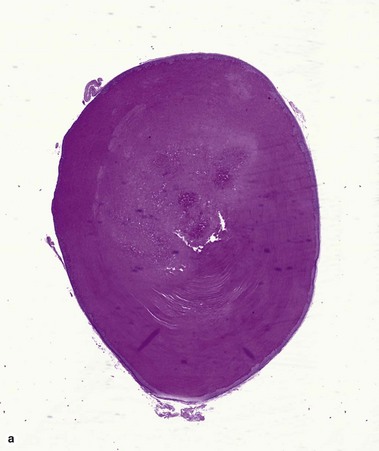

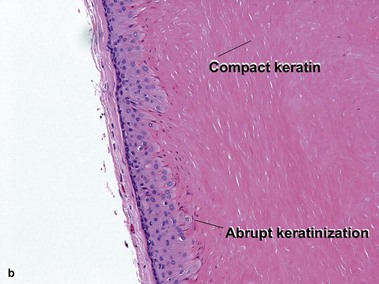

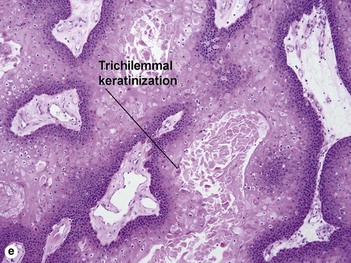

Pilar cyst (trichilemmal cyst, isthmus catagen cyst)

The abrupt keratinization of pilar cysts resembles that of the outer root sheath (the trichilemma).

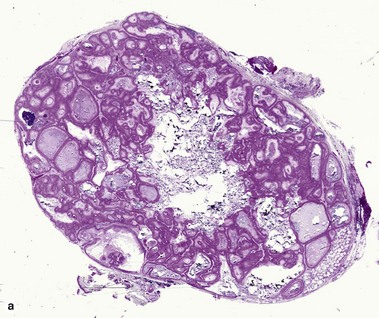

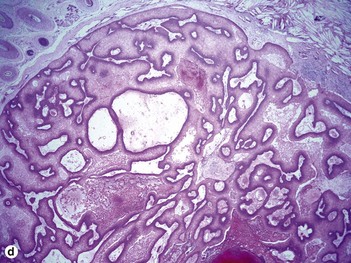

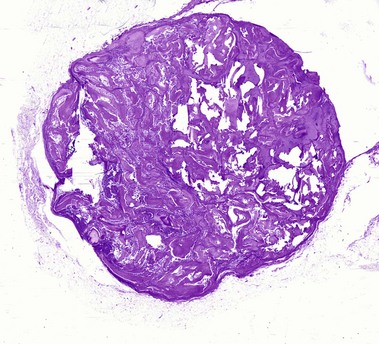

Proliferating pilar cyst

As the epithelium proliferates, the wall buckles inward, rolling on itself and producing a trabecular or scroll-like appearance (“rolls and scrolls”). A diagnosis of trichilemmal carcinoma should be suspected in tumors with a location other than scalp, recent rapid growth, size greater than 5 cm, infiltrative growth, significant cytologic atypia, and mitotic activity.

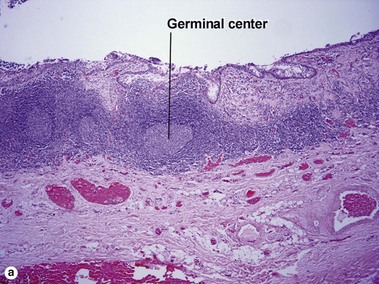

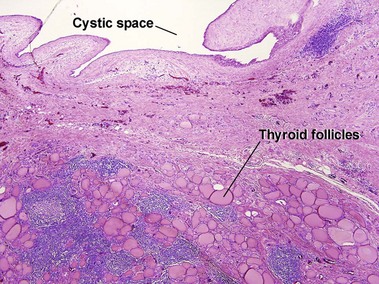

Branchial cleft cyst

Branchial cleft cysts are generally found on the lateral part of the neck, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. They may occur as a result of failure of obliteration of the second branchial cleft in embryonic development. Phylogenetically, the branchial apparatus may be related to gill slits. This analogy is helpful in remembering the typical location on the lateral neck. They are the most common cause of a congenital neck mass, and 2–3% of cases are bilateral.

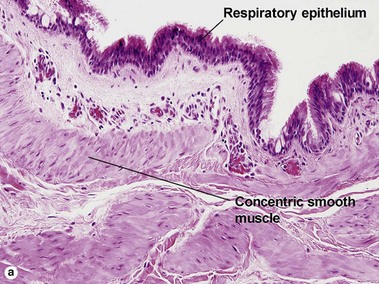

Bronchogenic cyst

Bronchogenic cysts are typically midline lesions, located in the suprasternal notch. Bronchogenic cysts are thought to result from remnants of the primitive foregut. Although bronchogenic cysts occur predominantly within the chest, cutaneous lesions generally present as neck lesions in children.

Steatocystoma (simple sebaceous duct cyst)

Steatocystomas are commonly inherited, with multiple lesions on the chest. The appearance resembles nodulocystic acne. Solitary lesions are common, and sporadic in occurrence. The cyst lining resembles that of the sebaceous duct. Sebaceous glands are common within the cyst wall, but may not be prominent. Some sections lack visible sebaceous glands, but the cyst can still be identified by the characteristic wavy eosinophilic cuticle.

Median raphe cyst

Median raphe cysts occur in men in a characteristic ventral location from the meatus to the anus. The cyst may first become apparent after intercourse. Median raphe cysts may result from incomplete embryonic fusion of the urethral folds, from ectopic periurethral glands of Littre, or sequestration of urethral epithelium after closure of the median raphe.

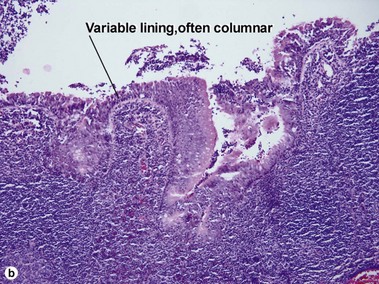

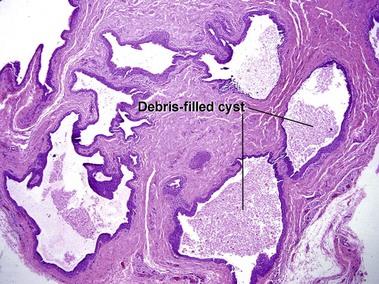

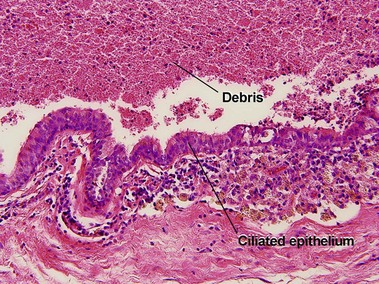

Cutaneous ciliated cyst

Although ciliated cysts typically occur on the legs of women, and are thought to relate to Müllerian duct remnants, they are occasionally noted in men. Ciliated cysts are commonly filled with debris, and the appearance of the cyst itself can be indistinguishable from that of a median raphe cyst. Helpful differentiating features are the location, sex of the patient, and characteristics of the surrounding skin. As ciliated cysts commonly occur on the legs, the skin lacks the typical appearance of genital skin.

Abbas, O, Wieland, CN, Goldberg, LJ. Solitary epidermolytic acanthoma: a clinical and histopathological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011; 25(2):175–180.

Argenyi, ZB, Huston, BM, Argenyi, EE, et al. Large-cell acanthoma of the skin. A study by image analysis cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994; 16(2):140–144.

Cho, S, Chang, SE, Choi, JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002; 29(3):152–156.

Folpe, AL, Reisenauer, AK, Mentzel, T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003; 30(8):492–498.

Fornatora, ML, Reich, RF, Haber, S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of the literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003; 25(1):12–15.

Jaworsky, C, Murphy, GF. Cystic tumors of the neck. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989; 15(1):21–26.

Kaddu, S, Dong, H, Mayer, G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma – “follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 47(3):423–428.

Kim, SH, Choi, JH, Sung, KJ, et al. Acantholytic acanthoma. J Dermatol. 2000; 27(2):127–128.

Martorell-Calatayud, A, Sanmartin-Jimenez, O, Traves, V, et al. Numerous umbilicated papules on the trunk: multiple warty dyskeratoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012; 34(6):674–675.

Mehregan, DR, Hamzavi, F, Brown, K. Large cell acanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2003; 42(1):36–39.

Romaní, J, Barnadas, MA, Miralles, J, et al. Median raphe cyst of the penis with ciliated cells. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22(4):378–381.

Santos, LD, Mendelsohn, G. Perineal cutaneous ciliated cyst in a male. Pathology. 2004; 36(4):369–370.

Sharma, R, Verma, P, Yadav, P, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumor of scalp: benign or malignant, a dilemma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012; 5(3):213–215.

Vidaurri-de la Cruz, H, Tamayo-Sánchez, L, Durán-McKinster, C, et al. Epidermal nevus syndromes: clinical findings in 35 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004; 21(4):432–439.