92

Benign Melanocytic Neoplasms

Benign Pigmented Cutaneous Lesions Other Than Melanocytic Nevi

• This group of lesions can further be divided into: (1) predominantly epidermal lesions (Table 92.1; Figs. 92.1–92.5); and (2) dermal melanocytoses (Table 92.2; Figs. 92.6 and 92.7).

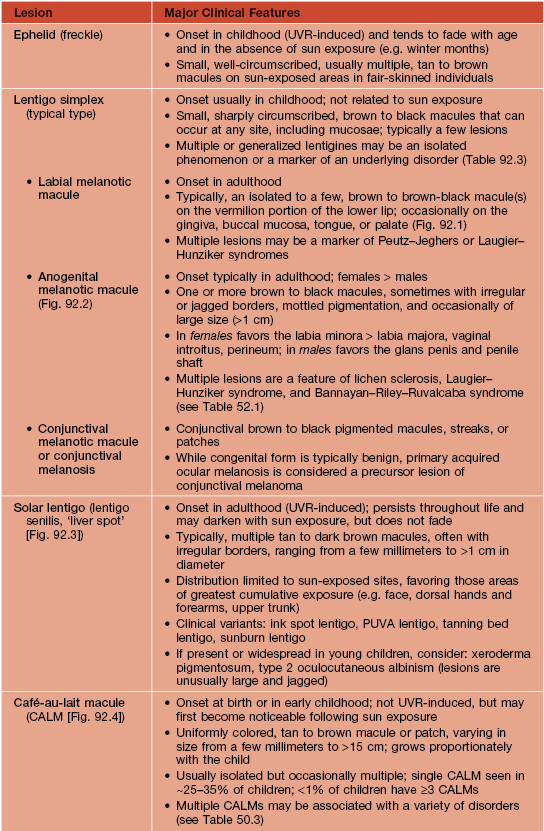

Table 92.1

Benign pigmented lesions other than melanocytic nevi (predominantly epidermal lesions).

PUVA, psoralens plus ultraviolet A phototherapy.

Fig. 92.1 Oral melanotic macules (labial lentigines). Multiple hyperpigmented macules on the lower lip in a patient with Laugier–Hunziker syndrome. Additional lesions are present on the tongue. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome can have a similar clinical appearance.

Fig. 92.2 Anogenital melanotic macules (anogenital lentiginosis). Biopsy of the darker lesion (at 7 o’clock) showed no cellular atypia. Over a period of 10 years, several of the macules faded. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 92.3 Solar lentigines. Numerous light brown macules, some of which have an irregular border, on chronically sun-exposed skin. Courtesy, Raymond Barnhill, MD.

Fig. 92.4 Café-au-lait macule. Large tan patch in a geographic pattern on the lateral trunk. The patient did not have McCune–Albright syndrome.

Fig. 92.5 Becker’s nevus. Large patch of hyperpigmentation on the leg, which is medium brown in color. These lesions may be misdiagnosed as café-au-lait macules or congenital melanocytic nevi, especially when they do not occur on the upper trunk. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

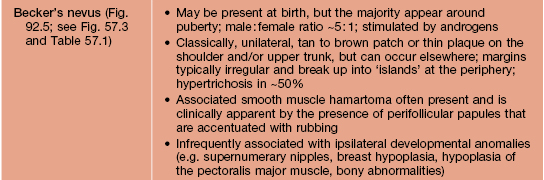

Table 92.2

The spectrum and clinical features of dermal melanocytoses.

* DDx for nevus of Ota or Ito: patch or plaque blue nevus, ecchymosis, venous malformation; for nevus of Ito: extra-sacral Mongolian spot.

** Rx (if desired): pulsed Q-switched lasers (e.g. Q-switched ruby, alexandrite, or Nd:YAG lasers) beneficial but often requires multiple sessions.

CALM, café-au-lait macule.

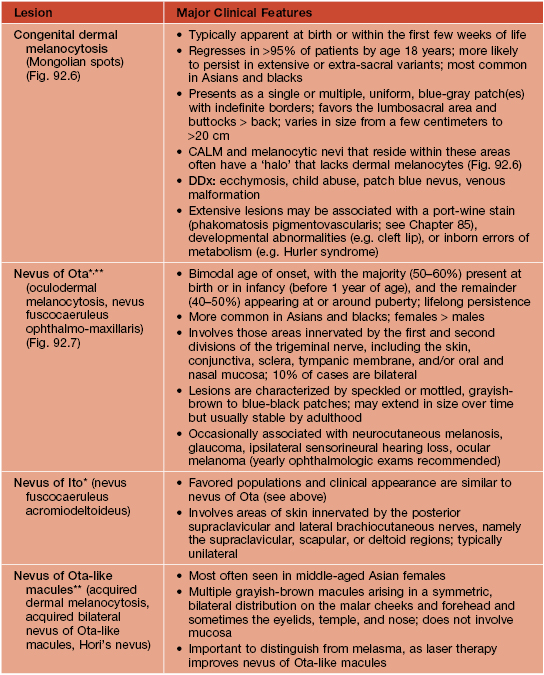

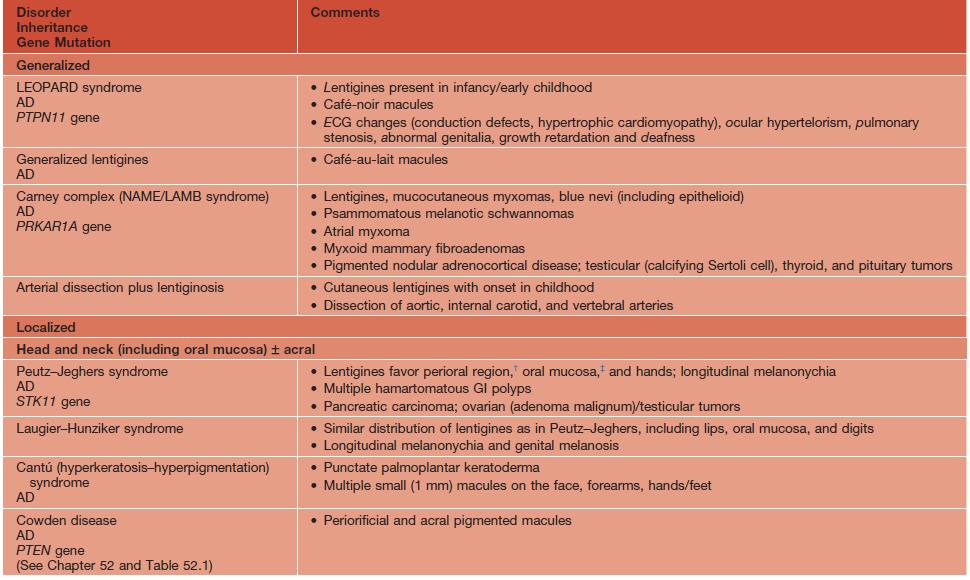

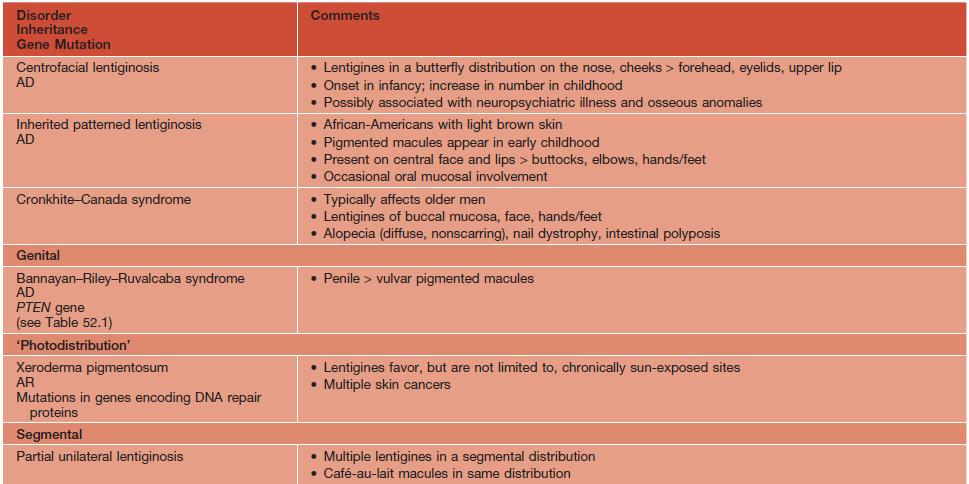

Table 92.3

Disorders associated with multiple lentigines.

† May fade.

‡ Persists.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; ECG, electrocardiogram; GI, gastrointestinal; LEOPARD, lentigines/ECG abnormalities/ocular hypertelorism/pulmonary stenosis/abnormalities of genitalia/retardation of growth/deafness syndrome; NAME, nevi/atrial myxoma/myxoid neurofibroma/ephelides syndrome; LAMB, lentigines/atrial myxoma/mucocutaneous myxoma/blue nevi syndrome.

Adapted from Bolognia JL. Disorders of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. In Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N (eds.), Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006;997–1040.

Fig. 92.6 Dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots) in a child with neurofibromatosis 1. Surrounding each café-au-lait macule, there is an absence of the characteristic blue discoloration.

Acquired Melanocytic Nevi (Moles)

• Benign proliferations of a type of melanocyte called a ‘nevus cell’.

• Both ‘ordinary’ melanocytes and nevus cells can produce melanin.

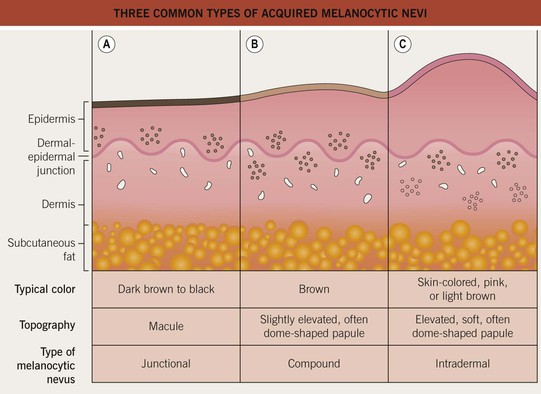

• Acquired melanocytic nevi can be categorized as common (banal) or atypical (dysplastic), and they are further named based on the histologic location of the collections of nevus cells (Fig. 92.8):

– Junctional melanocytic nevus: dermal-epidermal junction.

– Compound melanocytic nevus: dermal–epidermal junction plus dermis.

– Intradermal melanocytic nevus: dermis.

Fig. 92.8 Three common types of acquired melanocytic nevi. A Junctional, B compound, and C intradermal. The latter may also be pedunculated or papillomatous (see Chapter 1).

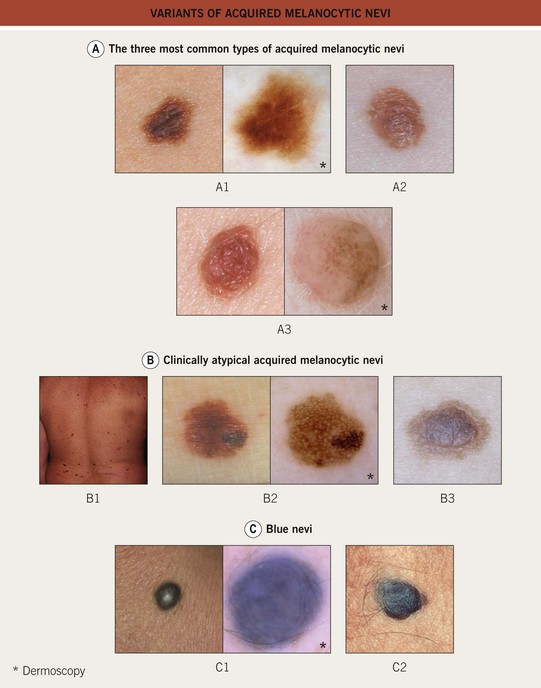

• Variants include halo, blue, Spitz, and ‘special site’ nevi (Fig. 92.9).

Fig. 92.9 Variants of acquired melanocytic nevi. A The three most common types of acquired melanocytic nevi. A1 Junctional nevus. Clinically, a brown macule with central hyperpigmentation. Dermoscopically, a uniform pigment network. A2 Compound nevus. Light to medium brown papule. A3 Intradermal nevus. A light tan, soft, raised papule. Dermoscopically, focal globular-like structures, whitish structureless areas, and fine comma vessels. B Clinically atypical acquired melanocytic nevi. B1 Multiple pigmented macules and papules of varying sizes on the back. B2 Close-up photo; the dermoscopy pattern is reticular-disorganized and can be seen with uncertain lesions. B3 ‘Fried egg’ appearance, with a central elevated soft papule and macular rim. C Blue nevi. C1 Common blue nevus. By dermoscopy, blue homogeneous color typically found in blue nevi. C2 Cellular blue nevus. A firm blue plaque is a common presentation. D Spitz nevi. D1 Classic Spitz nevus. Red dome-shaped papule on the ear of a child. D2 Reed nevus, typified dermoscopically by the classic starburst pattern (regular streaks at the periphery of a heavily pigmented and symmetric small macule). E Nevi of ‘special sites’ (e.g. scalp, acral, genital, milk-line). E1 Acral nevus. A brown macule on the sole of the foot. Dermoscopically, a lattice-like pattern is seen. F Other ‘specially named’ nevi. F1 Eclipse nevus. A tan center and thinner brown rim; note the stellate appearance of the brown rim. F2 Cockade or target nevus. Central lightly pigmented papule surrounded by a tan annulus then a brown ring. F3 One variant of combined melanocytic nevus. Dark brown to black papule within an otherwise uniformly pigmented light brown nevus. The differential diagnosis includes the possibility of a melanoma developing in a nevus. F4 Recurrent nevus. Dark brown pigmentation within the center of a circular scar; the pigmentation reflects the proliferation of melanocytes within the epidermis. Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, Jean L. Bolognia, MD, Lorenzo Cerroni, MD, Harold S. Rabinovitz, MD, Ronald P. Rapini, MD, and Iris Zalaudek, MD.

• Persons with more darkly pigmented skin will typically have darker colored nevi.

• Rx: it is not necessary to remove clinically atypical nevi prophylactically in order to confirm the presence of histological atypia; biopsies of nevi are indicated primarily when a severely atypical nevus or cutaneous melanoma is in the DDx (Table 92.4); if banal nevi become irritated (e.g. by clothing or jewelry), shave removal can be done.

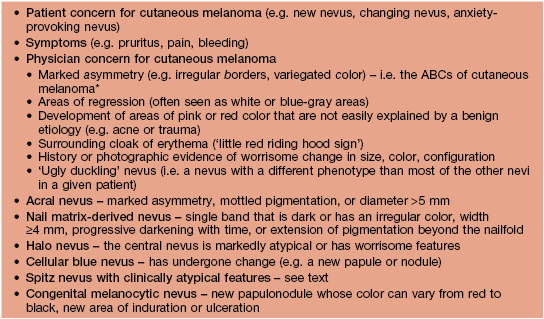

Table 92.4

Potential indications for biopsy of melanocytic nevi.

Patients with numerous nevi can continue to develop new nevi, and banal nevi can increase in size over time.

* D and E represent large diameter and evolution.

• When cutaneous melanoma is in the DDx, complete removal of the nevus is recommended as well as submission to a dermatopathologist; removal can be accomplished by several methods (see Fig 1.6); providing additional information (e.g. eccentric hyperpigmented area) is also helpful.

Common (Banal) Acquired Melanocytic Nevi

Atypical (Dysplastic or Clark’s) Acquired Melanocytic Nevi

• The major risk factor for developing atypical nevi is genetic predisposition.

• Atypical nevi often appear around puberty and are thought to develop throughout life.

• Clinically, atypical nevi are recognized by various features – e.g. varied colors (pink, brown, tan), a ‘fried-egg’ appearance with a papular component and a macular rim, a larger size than banal nevi, and borders that are ill-defined, ‘fuzzy,’ and sometimes notched or irregular (see Fig. 92.9).

Halo Nevus

• The halo of depigmentation is believed to represent a T-cell-mediated immune response against nevus antigens, analogous to vitiligo (see Chapter 54).

• The most common location is the back; multiple halo nevi are seen in ~50% of cases.

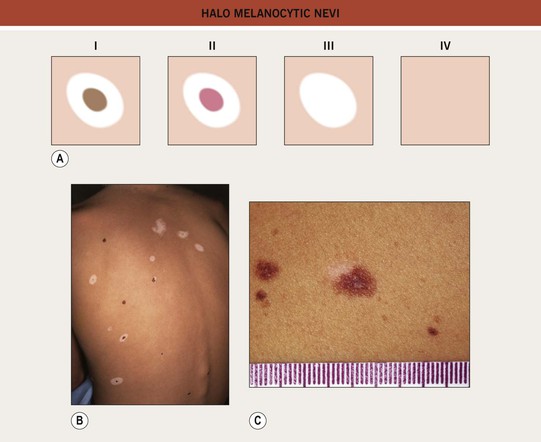

• There are four clinical stages in the life of a halo nevus, and the evolution usually occurs over years to decades (Fig. 92.10).

Fig. 92.10 Halo melanocytic nevi. A Four potential clinical stages in the life of a halo nevus. Stage I: central pigmented melanocytic nevus with a halo of depigmentation; Stage II: central nevus is pink with a halo of depigmentation; Stage III: no central nevus, just a depigmented macule; Stage IV: repigmentation (partial or complete). B Multiple halo nevi (seen here in all four of the various stages) are seen most commonly in children and young adults with numerous nevi. C A benign compound melanocytic nevus with an asymmetric halo. C, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• The central nevus should be assessed for suspicious or clinically atypical features; if none are present, then no treatment is necessary (vast majority of lesions); if present, then biopsy of just the central nevus should be performed.

Blue Nevi

• The common blue nevus typically presents as a solitary, blue to blue-black, dome-shaped papule, usually <1 cm in diameter and most often occurring on the dorsal hands or feet (see Fig. 92.9); frequently arises in adolescence; no malignant potential.

• The cellular blue nevus tends to be larger in size (i.e. more plaque-like), and it can be congenital or acquired (see Fig. 92.9); favors the head, sacral region, and buttocks; melanoma (malignant blue nevus) can develop within cellular blue nevi (see Chapter 93); if location (e.g. scalp) or patient awareness prevents satisfactory observation, then complete excision can be performed.

• Multiple blue nevi (normal in Asians) may signify an underlying syndrome, e.g. Carney complex (see Table 92.3).

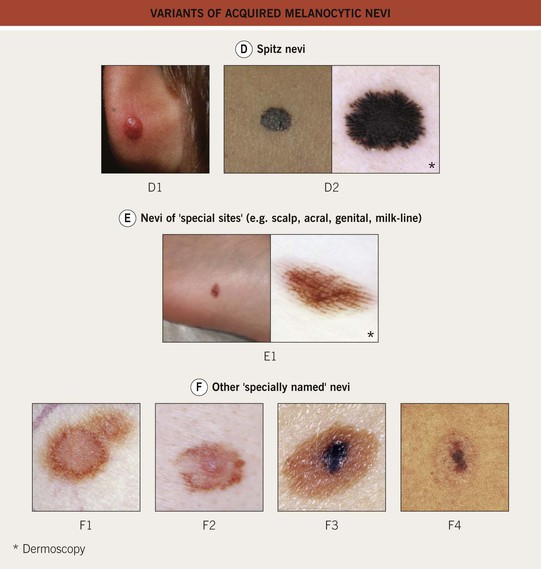

Spitz Nevi (Spindle and Epithelioid Cell Nevi)

• Benign proliferations of epithelioid and/or spindled melanocytes.

• Classically, a Spitz nevus is symmetric, well-circumscribed, <1 cm in diameter, uniformly pink, tan, red, or red-brown, smooth, and dome-shaped (see Fig. 92.9); occasionally, lesions are verrucous or darkly pigmented.

• Pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed is a variant that typically presents in young women as a very dark brown to black minimally elevated papule, most often on the thigh; characteristic ‘starburst pattern’ on dermoscopy (see Fig. 92.9).

• Any Spitz nevus with unusual features histologically should be completely excised.

Nevi of Special Sites

• Nevi in certain anatomic locations (e.g. scalp) may exhibit atypical clinical features, whereas those in several specific sites (e.g. acral, genital, auricular, milk line, flexural, and scalp nevi) may have atypical histologic features that simulate cutaneous melanoma (see Fig. 92.9).

• Recognition of this phenomenon prevents overdiagnosis of cutaneous melanoma.

Other ‘Specially Named’ Nevi

• Eclipse nevus: benign melanocytic nevus most often found on the scalp of children; presents as a tan, occasionally pink, central macule or papule with a brown, often stellate rim (see Fig. 92.9); ages into an intradermal nevus; when present on the scalp, may be a marker for developing numerous nevi elsewhere over time.

• Cockade nevus: a benign melanocytic nevus with a target configuration, namely a central pigmented papule surrounded by a concentric tan rim, which is then surrounded by another pigmented annulus (see Fig. 92.9); occurs in patients with eclipse nevi.

• Recurrent nevus: the reappearance of pigment within the scar of a previously biopsied or excised nevus (see Fig. 92.9); if symmetric, re-evaluation of the original histology and observation is generally all that is required; if asymmetric or continues to enlarge after its initial appearance, then biopsy is prudent.

• Agminated nevus: a clustering of melanocytic nevi within normal-appearing skin.

Congenital Melanocytic Nevi (CMN)

• CMN are classified into four groups, based on their final adult size:

– Small CMN: <1.5 cm (Fig. 92.11A).

Fig. 92.11 Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN). A Small CMN. Note the hypertrichosis and slight heterogeneity in pigmentation, reflecting its hamartomatous nature. B Medium-sized CMN. Note the pebbly appearance on clinical examination and the globular pattern with hyphae-like structures on dermoscopy (C). D Multiple medium-sized CMN. This patient had 25–30 such lesions. This presentation can be associated with neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM). E Giant CMN, also called a ‘bathing suit’ nevus. It is situated in a posterior axial location with numerous satellite nevi, some of which have hypertrichosis. This patient died of intractable ascites due to the migration of benign melanocytes from the brain to the peritoneal cavity via his VP shunt. In the perianal region, the nevus was softer and somewhat ‘boggy’ due to neurotization. A, Courtesy, Lorenzo Cerroni, MD; B, C, Courtesy, Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, and Harold S. Rabinovitz, MD; D, E, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

– Medium CMN: 1.5–20 cm (Fig. 92.11B–D).

– Large CMN: >20–40 cm (in a neonate, large CMN are >9 cm on the head or >6 cm on the body).

– Giant CMN: >40 cm (Fig. 92.11E).

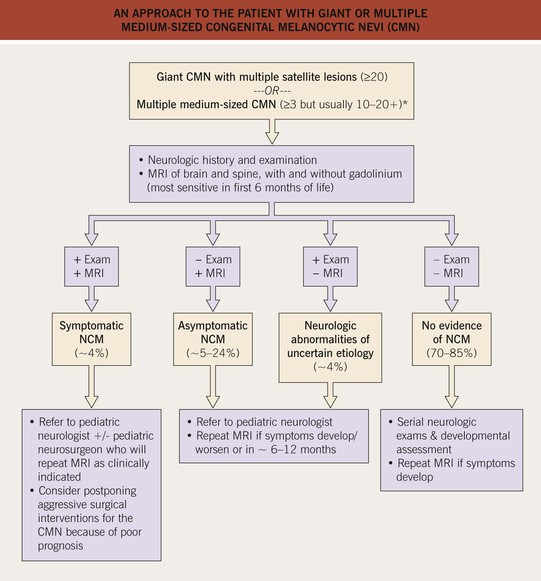

• An approach to the management of CMN is presented in Table 92.5 and Fig. 92.12.

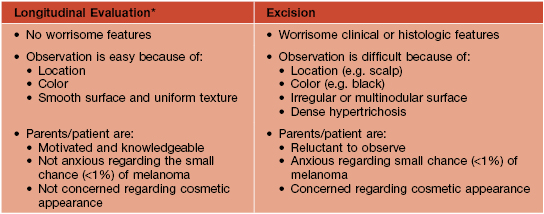

Table 92.5

Approach to the patient with a small or medium-sized congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN).

* Includes baseline photography, measurements, and periodic skin examinations.

Fig. 92.12 An approach to the patient with giant or multiple medium-sized congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN). For large lesions that are on an extremity or the abdomen, with few, if any, satellite lesions, the risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is low. *A higher proportion of these patients may have NCM compared to those with a giant CMN with multiple satellite lesions.

Speckled Lentiginous Nevus (SLN, Nevus Spilus)

• A subtype of CMN with a prevalence of ~2% in the general population.

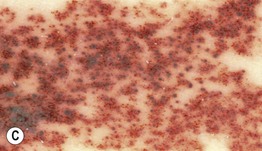

• Often presents at or around birth as a tan patch; over time numerous macules and papules develop within the tan patch, ranging from lentigines to junctional, compound and intradermal nevi to Spitz and blue nevi (Fig. 92.13).

Fig. 92.13 Speckled lentiginous nevus (nevus spilus). Multiple brown macules and papules superimposed upon a tan patch. Courtesy, Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, and Harold S. Rabinovitz, MD.

• DDx: agminated nevi (see above); partial unilateral lentiginosis.

For further information see Ch. 112. From Dermatology, Third Edition.