CHAPTER 46 Benign disease of the breast

Stages of Human Breast Development

The lifecycle of the breast involves three main stages: development (and early reproductive life), mature reproductive life and involution. The mammary buds develop during the sixth week as outgrowths of epidermis into the underlying mesenchyme. These mammary buds develop as downgrowths from mammary crests, which are thickened strips of ectoderm extending from the axilla to the inguinal region. During the fourth week, the mammary crests appear and persist in humans in the pectoral region where the breasts develop (Sandler 2006). Several mammary buds developing from each primary bud eventually form lactiferous ducts, and by gestation 15–20 lactiferous ducts are formed. The adipose tissue and fibrous connective tissue of the breast develop from the surrounding mesenchyme. In the late fetal period, the epidermis at the origin of the mammary gland forms a shallow mammary pit, from which the nipples arise soon after birth due to epithelial proliferation of the surrounding connective tissue of the areola. At birth, the mammary glands of males and females are identical, enlarged and, on occasion, may produce a secretion called ‘witch’s milk’. The mammary gland remains undeveloped until puberty, with only the main lactiferous duct formed.

Breast development proceeds identically in boys and girls until puberty. During puberty, the female breast enlarges rapidly. The elevated level of circulating oestrogens causes growth of the ductal system; however, progesterones, growth hormone, prolactin and corticoids also play a role. During pregnancy, an increase in the number of lobules and a loss of fat occurs due to raised oestrogen levels and a sustained increase in the level of progesterone. The intralobular ducts form buds that become acini; the lactating breast is composed of dilated acini that contain milk. During weaning, following the suckling stimulus, the breast involutes and the secretory cells are removed by apoptosis and phagocytosis (Howard and Gusterson 2000). The two-layer epithelium of the breast is reformed following weaning. Following successive pregnancies and periods of involution, the terminal duct lobular units (the functional unit of the breast) increase and decrease in size, with an increase and decrease in the number of acini. During involution, the breast stroma is replaced by fat and, as a result, the breast becomes less radiodense, softer and more ptotic (Dixon 1994).

Congenital Abnormalities

These disorders are not uncommon referrals at breast clinics and can cause considerable concern.

Accessory breast tissue and supernumerary nipples

Accessory breast tissue consists of ectopic breast tissue resulting from the failure of the embryonic mammary ridge to regress, commonly found in the anterior axillary line (Qian et al 2008). This occurs in 0.4–0.6% of the population, although is more common in Asian women, and is bilateral in one-third of cases. Accessory breast tissue can cause discomfort, cosmetic problems and restriction in arm movement. This breast tissue may become prominent during pregnancy, and both benign and malignant conditions may occur within this tissue. An explanation of the ‘abnormality’ and reassurance is often all that is required, and surgical excision should be reserved for symptomatic patients as a good cosmetic outcome is difficult and associated with significant morbidity.

Breast hypoplasia and Poland syndrome

Poland syndrome is a group of conditions in which amastia develops with varying degrees of absence of the pectoralis muscles and syndactyly, affecting one in 30,000 live births (Figure 46.1). It was first described by Alfred Poland in 1841, whilst he was a medical student at Guys Hospital, London (Ram and Chung 2009). Subsequent reports have added numerous additional components to the syndrome including mammary hypoplasia, costal cartilage defects and rib defects. One study evaluating 75 patients showed 100% with an absence or hypoplasia of the pectoralis major, 67% with a hand abnormality, and 49% with athelia (congenital absence of one or both nipples) and/or amastia (breast tissue, nipple and areola is absent; differs from amazia which only involves the absence of breast tissue, and the nipple and areola remain present) (Katz et al 2001). The syndrome is almost always unilateral, with the right side more often affected than the left side, and is more common in men than women (3:1). Patients with Poland syndrome often request reconstruction of the muscular defect, producing symmetry and improving psychological well-being. This can be performed with an ipsilateral latissimus dorsi pedicled flap with or without an implant.

Aberrations of Normal Development and Involution

Fibroadenoma

Simple fibroadenoma

These are discrete, firm, highly mobile, benign breast masses which may present symptomatically or as an incidental screening finding. Fibroadenomas usually present unilaterally; however, in 20% of cases, multiple lesions may present in the same breast or bilaterally. They are found most commonly at the time of greatest lobular development in women aged 15–35 years. The encapsulation explains the motility of the masses, making them appear more superficial than they truly are (Figure 46.2). Fibroadenomas develop from the special stroma of the lobule. They are hormone dependent, lactate during pregnancy and involute with the rest of the breast in the perimenopause (Hughes et al 1987). A direct association has been reported between use of the oral contraceptive pill before the age of 20 years and risk of fibroadenoma. The Epstein–Barr virus is thought to play a causative role in the development of this tumour in immunosuppressed patients (Kleer et al 2002). Observation of fibroadenomas in younger women showed that 55% do not change size, 37% get smaller and 8% increase in size. Fifty percent of fibroadenomas contain other proliferative changes such as adenosis, sclerosing adenosis and duct epithelial hyperplasia; these are known as ‘complex fibroadenomas’. Complex fibroadenomas, but not simple fibroadenomas, are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Carter et al 2001). Fibroadenomas in older women or in women with a family history of breast cancer have a higher risk of associated breast cancer (Dupont et al 1994, Shabtai et al 2001).

Fibroadenomas over 5 cm in size are known as ‘giant fibroadenomas’, and are seen more commonly in women of African origin. Cancers rarely appear within a fibroadenoma. Patients with a histologically confirmed fibroadenoma can be managed conservatively, with follow-up imaging at 6 months to confirm that the lesion is not increasing in size. Excision is recommended if the mass increases in size, if it is larger than 3–4 cm or at the patient’s request. Recurrence is rarely due to incomplete excision, and is often due to an undiagnosed adjacent mass. A minimally invasive technique, such as ultrasound-guided cryoablation, is a treatment option for fibroadenomas in women who do not wish to have surgery (Caleffi et al 2004). Rapid growth of a fibroadenoma can occur in adolescence (juvenile fibroadenoma) or in women of perimenopausal age. Juvenile fibroadenomas usually present as painless, solitary unilateral masses over 5 cm in size (reaching up to 15–20 cm). Although benign, surgical excision of these masses is advised (Wechselberger et al 2002).

Phyllodes tumour

Johannes Muller (1838) first described a large mammary tumour with a cystic appearance and leaf-like growth pattern; he named this ‘cystosarcoma phyllodes’. Treves and Sunderland (1951) proposed that benign, premalignant and malignant forms of this disease existed. The term ‘phyllodes tumour’ (PT) was adopted by the World Health Organization in 1981 to describe this rare fibroepithelial lesion, which accounts for less than 1% of all breast neoplasms. They are less common than fibroadenomas (ratio 1:40), from which they need to be distinguished. PTs can present in women of any age, including adolescents and the elderly, but the majority occur in women aged 35–55 years; the median age of presentation is 45 years. PTs present clinically as a well-circumscribed, mobile mass which may be growing rapidly. The size of presentation of PTs is larger than that for fibroadenomas, although with increased breast awareness and the advent of breast screening, there has been a trend towards smaller tumours. Other signs and symptoms include dilated skin veins, blue skin discolouration, nipple retraction, fixation to the skin or pectoralis muscle, and pressure necrosis of the skin. Palpable axillary lymphadenopathy has been identified in up to 20% of patients, but axillary metastatic involvement is rare. PTs are more commonly found in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Prevalence is higher in Latin American White and Asian populations. Certain clinical features may raise the index of suspicion, including a sudden increase in a longstanding breast mass, a fibroadenoma over 3 cm in size in a patient aged over 35 years, lobulated appearance on mammography, cystic areas within a solid mass on ultrasonography, and indeterminate features on fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) (Jacklin et al 2006). PTs are often not clinically distinguishable from fibroadenomas.

Diagnosis of PTs by FNAC is associated with a high false-positive rate due to the heterogeneity of the tumours. The risk of sampling error is reduced following a core biopsy. Criteria have been formulated to help physicians to select patients for core biopsy — the Paddington Clinicopathologic Suspicion Score (Jacklin et al 2006). Twenty-five percent of PTs are categorized as malignant and more than 50% are categorized as benign, with a number of prognostic factors implicated in the risk of local and distant recurrence including tumour size, grade and margin status. Benign PTs have the potential to recur locally, and rarely present at distant sites. Despite having an increased risk of distant spread (20%), malignant lesions have a 15-year survival rate of 89%.

Nipple Discharge

Ductoscopy allows direct visualization of the discharging duct, and biopsy, by a microendoscope, was investigated by Okazaki in the early 1990s. The procedure is carried out using local anaesthesia (topical local anesthetic cream plus intradermal local anesthetic injection at the areolar margin) and has no significant complications (Escobar et al 2006). An endoscope is inserted through the duct opening on the nipple surface after dilating the duct with a probe (e.g. lacrimal dilator), and saline solution is injected into the duct through the channel to widen it and facilitate the passage of the endoscope, enabling visualization of the intraductal space (Escobar et al 2006). Whilst ductoscopy can be used as a diagnostic and therapeutic addition in patients with nipple discharge, there is no evidence to support its use in the management or early detection of breast cancer.

The aetiology of non-surgically-treated nipple discharge can be grouped into four categories:

Intraductal papilloma and papillomatosis

Intraductal papillomas are benign intraductal proliferations, usually found in the major ducts beneath the nipple (lactiferous sinuses); however, they can be found anywhere in the breast. The term ‘papilloma’ describes the fibrovascular cores covered by a double layer of cells comprising an outer myoepithelial layer and an inner luminal cell layer (Mallon et al 2000). The cells are cytologically benign. Squamous and apocrine metaplasia are common findings. There are three types of intraduct papilloma: solitary, multiple or juvenile papillomas. Solitary duct papillomas are the most common; these occur in large ducts (within 5 cm of the nipple) and present with either bloody or a serous single duct discharge (Figure 46.3). Two studies have demonstrated a correlation between the presence of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) in a papillary lesion on needle core biopsy and the presence of invasive or in-situ carcinoma of the breast in the excisional biopsy (Agoff and Lawton 2004, Ivan et al 2004). It has been suggested that the risk of recurrence of papilloma is related to the presence of proliferative breast lesions in the surrounding breast tissue (MacGrogan and Tavassoli 2003). Papillomatosis (multiple intraductal papillomas; 10% of intraductal papilloma) is defined as a minimum of five discrete papillomas within a localized segment of breast tissue. Papillomatosis tends to occur in younger patients and is less often associated with nipple discharge. Multiple papillomas are more frequently peripheral, bilateral, present as a palpable mass and have a higher probability of having an in-situ or invasive carcinoma than central papilloma. Thorough radiological imaging of the contralateral breast is required to exclude malignancy (Ali-Fehmi et al 2003). Multiple papillomas are associated with an increased risk of developing subsequent breast cancer (Krieger and Hiatt 1992, Page et al 1996, Levshin et al 1998). Juvenile papillomatosis is a rare condition defined as severe ductal papillomatosis occurring in women under 30 years of age (median age 20 years). It often presents as a discrete mass up to 8 cm in diameter, and consists of a mixture of cysts, nodules of sclerosing adenosis and complex intraduct proliferations containing myoepithelial cells and luminal cells. Due to the holes seen in the cut surface of the tumour, it has been called ‘Swiss cheese disease’. A number of studies have suggested an association between juvenile papillomatosis and familial breast cancer; therefore, long-term follow-up is advised (Bazzocchi et al 1986).

Mastalgia

The majority of patients can be managed by exclusion of cancer and reassurance. Evening primrose oil (EPO) was previously used in the treatment of mastalgia, but has recently been withdrawn from prescription by the Medicines Control Agency. A recent randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 121 women comparing EPO and fish oil with control oils in the treatment of mastalgia showed no clear benefit from either EPO or fish oils (Blommers et al 2002). This study showed that 33% of women with cyclical mastalgia and 17% of women with non-cyclical mastalgia showed an improvement in symptoms with EPO compared with the control group (46% and 17% improvement, respectively). Other agents have shown some benefit, including phytoestrogens (soya milk) and Vitex agnus-castus (a fruit extract). A reduction in dietary fat intake has also been shown to improve symptoms. Second-line treatments include tamoxifen 10 mg daily and danazol 200 mg daily. Tamoxifen given in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle controlled mastalgia in 85% of women, with recurrent pain noted in 25% of patients at 1 year. Tamoxifen has been found to be superior to danazol with a better toxicity profile. Fifty-three percent of patients receiving tamoxifen compared with 37% of patients receiving danazol were pain-free after 1 year. It is important to note that tamoxifen is not licenced for use in mastalgia. Due to the high toxicity rate (80%), bromocriptine is no longer used in the treatment of mastalgia.

Fibrocystic Change

Fibrocystic change (FCC; also called fibrocystic disease, cystic mastopathy, chronic cystic disease, mazoplazia, Reculus’s disease) is the most common benign disorder of the breast, affecting women between 20 and 50 years of age (Cole et al 1978, Hutchinson et al 1980, Cook and Rohan 1985, La Vecchia et al 1985, Bartow et al 1987, Sarnelli and Squartini 1991, Fitzgibbons et al 1998). FCC is observed in approximately 50% of women clinically and in 90% histologically (Love et al 1982). The most common symptoms of FCC are breast pain and tender nodularity. FCC is thought to be due to a hormonal imbalance, particularly the predominance of oestrogen over progesterone; however, the pathogenesis is not completely understood (Dupont and Page 1985). FCC is made up of cystic lesions (macrocystic and microcystic) and solid lesions, and includes adenosis, epithelial hyperplasia with or without atypia, apocrine metaplasia, papilloma and radial scar. FCC can be classified into non-proliferative lesions, and proliferative lesions with or without aytpia (atypical hyperplasia) (Dupont and Page 1985).

Non-proliferative lesions are not associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer; however, women with proliferative disease without atypia and with atypia are at greater risk of breast cancer (relative risk 1.3–1.9 and 3.9–13.0, respectively) (Dupont and Page 1985, Palli et al 1991, Dupont et al 1993, Marshall et al 1997). Age is thought to play a key role, with the risk of breast cancer in young women with a diagnosis of atypical epithelial proliferation twice that of a women over 55 years of age with a similar diagnosis (Hartmann et al 2005).

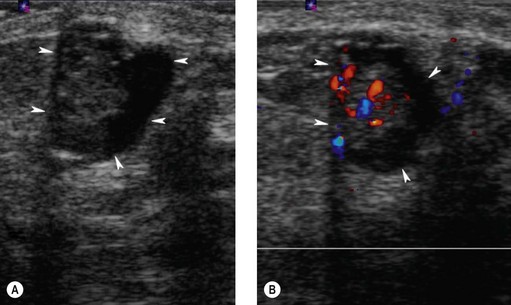

Breast cysts

Breast cysts are fluid-filled, ovoid/round structures affecting one-third of women between 35 and 50 years of age. The majority are subclinical ‘microcysts’, but approximately 20–25% are palpable ‘macrocysts’ which are a common presentation at breast clinics (Haagenson 1986). Macrocysts are often multiple and appear in the fifth decade. Cysts are derived from the terminal duct lobular unit, and in most cysts, the epithelial lining is either flattened or absent (non-apocrine cysts). In a few cysts, the apocrine epithelial lining can be observed (apocrine cysts). Apocrine cysts have a higher recurrence rate than non-apocrine cysts (Dixon et al 1999). Breast cysts have mammographically characteristic halos, but cannot be reliably distinguished from solid masses; therefore, ultrasonography and fine needle aspiration (if indicated) are used for diagnosis (Figure 46.4). Ultrasonography can also distinguish between simple and complex cysts, and a cyst wall with any projections may indicate carcinoma or an intracystic papilloma which necessitates either a core needle biopsy or a surgical excision biopsy (Vargas et al 2004, Houssami et al 2005). Complex (complicated/atypical) cysts, reported in approximately 5% of all breast ultrasounds, are characterized by internal echoes or thin septations, thickened and/or irregular wall, and absent posterior enhancement (Houssami et al 2005). Asymptomatic cysts are left alone but large painful cysts can be aspirated to dryness. Any bloodstained fluid should be sent for histology, and if a palpable mass is still evident after aspiration, further investigations are indicated. Cysts may recur following aspiration. There is a slightly increased relative risk of breast cancer in women with cysts.

Adenosis

Adenosis of the breast is characterized by an increase in either the number or size of glandular components, usually involving the lobular units. Sclerosing adenosis is a benign lesion of disordered acinar, myoepithelial and connective tissue which can mimic carcinoma (Jensen et al 1989). It can present as a palpable mass or as a suspicious finding at mammography, and is associated with other proliferative lesions including epithelial hyperplasia, papillomas, complex sclerosing lesions, apocrine changes and calcification. A number of studies have shown that it is a risk factor for invasive cancer. Microglandular adenosis is characterized by a proliferation of small, round glands distributed irregularly within dense fibrous and/or adipose tissue. Notably, microglandular adenosis lacks the outer layer of myoepithelia seen in other tissue types of adenosis. This lack of myoepithelial layer makes it difficult to differentiate from tubular carcinoma (Eusebi et al 1993). The absence of epithelial membrane antigen staining in the luminal epithelial cells, and the presence of basal lamina encircling glandular structures demonstrated by laminin or type IV collagen immunostaining distinguishes between microglandular adenosis and tubular carcinoma (Eusebi et al 1993). Microadenosis has a tendency to recur if not completely excised, and although it is defined as benign, there is growing evidence of the potential of this lesion to become invasive carcinoma (Acs et al 2003). Apocrine (adenomyoepithelial) adenosis is a variant of microglandular adenosis. Apocrine adenosis describes a wide spectrum of lesions, and in this case describes apocrine changes in the specific underlying lesion (deformed lobular unit, sclerosing adenosis, radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions) (O’Malley and Bane 2004). Tubular adenosis is a rare variant of microglandular adenosis that can be distinguished from tubular carcinoma by the presence of an intact myoepithelial layer around the tubules (Lee et al 1996).

Metaplasia

Apocrine metaplasia is characterized by columnar cells with granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and luminal cytoplasmic projections (Guray and Sahin 2006). These cells line dilated ducts and are more frequently seen in younger women. When the nuclei of the apocrine cells display significant atypia, this is known as ‘atypical apocrine metaplasia’. Clear cell metaplasia of the breast is morphologically similar to clear cell carcinoma; however, its immunohistochemical staining is similar to an ‘eccrine’ sweat gland (Vina and Wells 1989).

Epithelial hyperplasia

Ductal hyperplasia

Normal breast ducts are lined by two layers of cuboidal cells with specialized luminal borders and basal contractile myoepithelial cells. Epithelial hyperplasia is defined as an increase in cells within the ductal space. The degree of architectural and cytological features of the proliferating cells further classifies hyperplasia. Usual ductal hyperplasia has an increase in the number of cells without architectural distortion, and is not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Mild hyperplasia of usual type denotes a three- to four-cell layer of proliferating cells, whereas moderate hyperplasia describes a proliferating layer more than four cells thick. In florid hyperplasia, the lumen is distended and may be obliterated. The most important cytological feature of mild, moderate and florid hyperplasia is the mixture of cell types and variation in appearance of epithelial cells and their nuclei (Koerner 2004).

ADH is a type of hyperplasia that mimics low-grade DCIS. It is a rare condition seen in 4% of symptomatic benign biopsy lesions, and is often small and focal, involving a small part of the duct or a few ducts (Guray and Sahin 2006). More ADH lesions are being detected with the increased use of mammography. Thirty-one percent of biopsies due to microcalcifications show ADH (Pinder and Ellis 2003). Patients with ADH have a four to five times increased risk of developing breast cancer compared with the general population, and the risk is 10 times greater compared with the general population if the patient has a first-degree relative with breast cancer. The increased risk of breast cancer is higher in both the ipsilateral and contralateral breasts (Page et al 1985, Tavassoli and Norris 1990). Women with ADH have an increased risk of developing cancer within 10–15 years of diagnosis, with this risk declining after 15 years (Page et al 1985, Dupont and Page 1989). Premenopausal women with ADH have a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer than postmenopausal women. Routine follow-up of women with ADH is recommended.

Lobular hyperplasia

Atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular in-situ neoplasia are collectively termed ‘lobular neoplasia’ because, unlike ductal lesions (which are heterogeneous), the histological features of lobular epithelial proliferations are very similar. The significant difference between lobular in-situ neoplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia is the degree and extent of epithelial proliferation. Lobular neoplasia is a rare breast condition more prevalent in perimenopausal women, which rarely presents clinically and is often found as an incidental finding on biopsy. Both atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular in-situ neoplasia increase the risk for development of invasive carcinoma (four- and 10-fold, respectively). Subsequent invasive carcinoma after atypical lobular hyperplasia is three times more likely to occur in the ipsilateral breast (Page et al 2003). Carcinoma may arise 15–20 years after the initial diagnosis. The risk of developing subsequent invasive carcinoma after a diagnosis of lobular in-situ neoplasia is similar in both the ipsilateral and contralateral breasts.

Columnar cell lesions

Columnar cell lesions can be classified as either columnar cell change or columnar cell hyperplasia with or without atypia (Schnitt and Vincent-Salomon 2003). Atypical columnar cell lesions (also called flat epithelial atypia, blunt duct adenosis, columnar alteration of lobules, hypersecretory hyperplasia with atypia, pretubular hyperplasia, and columnar alteration with prominent snouts and secretions) have a low local recurrence rate and a low risk of progressing to invasive carcinoma. Some columnar cell lesions may represent a precursor of low-grade DCIS or invasive carcinoma, especially tubular carcinoma (Schnitt 2003). Columnar cell lesions diagnosed by needle core biopsy are advisedly excised to exclude in-situ or invasive cancer. Close follow-up of the patient is advised following excision (Nasser 2004). The radiological features of radial scars can mimic carcinomas, and the role of FNAC in diagnosis is limited. As malignancy cannot be excluded following needle core biopsy, excision biopsy of these lesions is advised.

Complex sclerosing lesion and radial scar

Stromal involution can produce areas of fibrosis. Radial scars are benign pseudoinfiltrative lesions of unknown significance, characterized by a fibroelastic core with entrapped ducts surrounded by radiating ducts and lobules showing variable epithelial hyperplasia, adenosis duct ectasia and papillomatosis. Radial scars and ‘complex sclerosing lesions’ (CSL) are usually asymptomatic and discovered through mammographic screening, but may present as a palpable mass. The term ‘radial scar’ has been used for lesions measuring less than 1 cm, whereas CSL is reserved for those lesions over 1 cm in size (Kennedy et al 2003, Patterson et al 2004). Radial scars have been shown to be associated with BBD and a doubling of the risk of developing breast cancer (Nielsen et al 1987, Jacobs et al 1999). This risk is increased in women with larger and/or multiple radial scars.

Proliferative Stromal Lesions

Diabetic fibrous mastopathy

This is a rare form of lymphocytic mastitis and stromal fibrosis which can occur in patients with longstanding type 1 diabetes who have severe diabetic microvascular complications. It occurs in premenopausal women and, rarely, in men. It is known as ‘diabetic mastopathy’ or sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis which does not predispose to breast carcinoma or lymphoma (Kudva et al 2003). Clinically, it is characterized by solitary or multiple ill-defined, painless, immobile, discrete lesions in one or both breasts. Mammographic and sonographic findings of these lesions are very suspicious for carcinoma; therefore, needle core biopsy is essential for diagnosis (Camuto et al 2000, Haj et al 2004). The pathogenesis of diabetic mastopathy is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune reaction to the abnormal accumulation of altered extracellular matrix in the breast, which occurs to connective tissue following hyperglycaemia (Haj et al 2004, Baratelli and Riva 2005). Annual follow-up is recommended in patients with diabetic fibrous mastopathy.

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia of the breast

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is a benign myofibroblastic proliferation of non-specialized mammary stroma. Clinicopathologically, it ranges from incidental, microscopic foci to mammographic and clinically palpable breast masses (Castro et al 2002, Guray and Sahin 2006). PASH is more common in premenopausal women and older women taking hormone replacement therapy; as a result, it was thought to be due to hormone stimulation, particularly progesterone. More recent studies have shown that only a small percentage of patients with PASH express either the oestrogen or progesterone receptor (Pruthi et al 2001, Castro et al 2002). PASH may present clinically as a well-circumscribed, dense rubbery mass mimicking a fibroadenoma or PT. As the mammographic and sonographic findings of PASH are non-specific, a needle core biopsy is required to exclude malignancy (Pruthi et al 2001, Mercado et al 2004). Wide local excision is the recommended treatment for PASH. It may recur but the prognosis is good (Castro et al 2002).

Breast Disorders Related to Pregnancy and Lactation

Lactogenesis

Ultrasound is the most appropriate radiological investigation to evaluate breast disorders in women during pregnancy and lactation. The use of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation and treatment of pregnant women should be avoided, and only used where the risk:benefit ratio is clear (Talele et al 2003, Espinosa et al 2005). There is no conclusive evidence that magnetic resonance imaging has a toxic effect on the developing embryo, and the use of gadolinium-based contrast during pregnancy is probably safe as the quantity of gadolinium crossing the placenta is low and is rapidly excreted by the kidneys (Nagayama et al 2002, De Wilde et al 2005, Webb et al 2005). The use of mammography during pregnancy remains controversial, but it should be performed if malignancy is suspected as it is particularly effective in detection of microcalcifications and subtle areas of distortion, which may not be detected on ultrasound. The impact of prenatal exposure to ionizing radiation depends on three factors: the stage of fetal development at the time of exposure, the anatomical distribution of the radiation and the radiation dose. The fetus is most susceptible to radiation-induced malformations in the first 2 months of pregnancy (organogenesis). These malformations are believed to occur with exposure to more than 0.005 Gy of radiation (Greskovich and Macklis 2000). Two-view mammography of each breast performed with abdominal shielding exposes the fetus to 0.004 Gy of radiation; therefore, mammography with abdominal shielding can be performed should it be required during pregnancy. Recommendations are to avoid mammography in the first trimester; ultrasonography is preferable (Osei and Faulkner 1999, Sabate et al 2007).

Gestational and secretory hyperplasia

Microcalcifications following pregnancy or lactation are detectable by mammography, and it is important to distinguish these from pregnancy-like hyperplasia which manifests with similar findings in non-pregnant, non-lactating women (Sabate et al 2007).

Bloody spontaneous nipple discharge

This is an uncommon condition during pregnancy and lactation, but does occasionally occur in the third trimester when the vascularity of the breast is increased and changes in the epithelium are more marked. Bloody spontaneous nipple discharge usually resolves with nursing, but can persist in severe cases. Nipple discharge is an uncommon symptom of pregnancy-associated breast cancer, but carcinoma must be excluded (Kline and Lash 1964, O’Callaghan 1981, Lafreniere 1990).

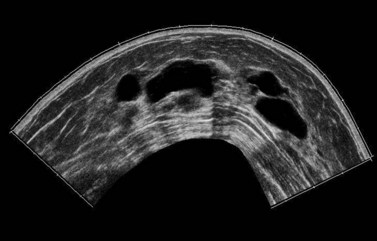

Galactocele

Galactoceles are the most common benign lesions in lactating women; however, they actually occur more frequently following cessation of breast feeding when the milk is retained (Scott-Conner 1997, Son et al 2006). Galactoceles are cuboidal or flat epithelium-lined cysts containing fluid resembling milk and inflammatory debris (Figure 46.5). The cysts form as a result of duct dilatation, and aspiration of the cyst is both therapeutic and diagnostic, producing milk during lactation and a more thickened milky fluid after lactation has ceased (Gomez et al 1986). Infection remains a common complication of galactoceles, and is easily confirmed with fine needle aspiration by a mixed purulent–milky material (Sabate et al 2007).

Pseudolipoma

Pseudolipoma occurs when the fat content of the breast is very high, and is a radiolucent mass.

Pseudohamartoma

Pseudohamartoma occurs when galactoceles contain variable proportions of old milk and water. The mass resembles a hamartoma as the high viscosity of old milk does not allow the separation of milk and water (Gomez et al 1986).

Gigantomastia

Gestational gigantomastia complicates between 1 : 28,000 and 1 : 118,000 deliveries (Lewison et al 1960, Beischer et al 1989). Gestational gigantomastia is a common phenotypic outcome from one or more aberrant growth-related pathways resulting in massive breast enlargement (Swelstad et al 2006). The diagnosis is one of exclusion. Medical management is usually ineffective but remains first-line therapy in the hope of avoiding surgery during pregnancy. Bromocriptine is the most common medical regimen, resulting in mild regression or arrest in breast hypertrophy. Effects are variable, usually temporary and do not restore breast volume to normal. If the quality of a woman’s life suffers significantly or endangers fetal viability, surgical management (reduction mammoplasty or simple mastectomy) should be utilized (Swelstad et al 2006). Bilateral mastectomy with delayed reconstruction provides the smallest risk of recurrence should the woman become pregnant again (Wolf et al 1995, Swelstad et al 2006).

Puerperal mastitis

Infection of the breast is uncommon during pregnancy, but affects between 5% and 33% of women at some point during lactation (World Health Organization 2000). A study following up 1075 breastfeeding women in Australia reported a 20% incidence of mastitis (Kinlay et al 1998). The wide variation in rates is probably because there is no standard definition of mastitis. The clinical spectrum of lactational mastitis (an acute inflammation of the interlobular connective tissue within the mammary gland, which may or may not be infective) ranges from focal inflammation to abscess with septicaemia. It most commonly develops in the early stages of feeding, with 74–95% of cases observed within the first 3 months of breast feeding (Devereux 1970, Marshall et al 1975, Foxman et al 2002). Cases have been reported as long as the woman is breast feeding. Three studies of breastfeeding women reported recurrent episodes of mastitis in 4–14.4% of cases (Fetherston 1997, Vogel et al 1999, Foxman et al 2002).

Mastitis is diagnosed on clinical symptoms and signs, and patients often present with pain, erythema and swelling. This can spread to affect the whole breast, with the patient becoming septic. It is usually unilateral and rarely presents at weaning. Breast examination often reveals oedema, erythema in a wedge-shaped distribution and tenderness (Bedinghaus 1997). If an abscess is present, a fluctuant mass may be palpable with overlying erythema. There are a number of predisposing factors for developing lactational mastitis including milk stasis [insufficient drainage of the breast, rapid weaning, oversupply of milk, pressure on breast (e.g from poorly fitting bra)], a blocked duct and skin breakdown of the nipple (e.g. fissure, cracks or blisters). Infections developing within the first few months are often due to organisms transmitted in hospital, and are therefore resistant to most commonly used antibiotics. One study has demonstrated that in the first month of breast feeding, more than half of women have nipples colonized with Staphylococcus aureus (Livingstone and Stringer 1999). Eczema is a risk factor for infection, as women with eczema are more likely to harbour S. aureus (Noble 1998, Amir 2002). Additional risk factors for colonization with meticillin-resistant S. aureus include caesarean birth, administration of antibiotics during labour or the early postpartum period, and multiple gestations (Morel et al 2002). Another potential risk factor is in-vitro fertilization, which requires mothers to return to hospital on numerous occasions. Maternal stress, fatigue, poor nutrition, and maternal or infant illness have been associated with mastitis, although the evidence is inconclusive.

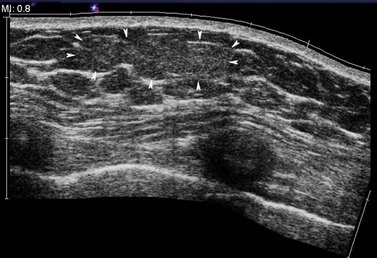

When infectious mastitis does occur, the organisms most often cultured from breast milk include S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (Lawrence 2005). Streptococcal infection should be suspected whenever bilateral mastitis presents in the postpartum period (Mead 1992). Delayed care or inadequate treatment can lead to abscess formation. Breast abscess is seen in 0.4–0.5% of lactating women, rarely occurring after the first 6 weeks of lactation. A 2004 study of more than 1000 women showed that 3% of women with breast inflammation will develop an abscess (Amir et al 2004). Abscesses can result in a functional mastectomy (defined as a breast that is unable to effectively lactate) in 10% of women (World Health Organization 2000). Ultrasound plays an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of mastitis if abscess formation is suspected. Abscesses can be treated successfully with needle aspiration to dryness under ultrasound guidance. The cavity is often irrigated with local anaesthetic to reduce pain followed by saline solution (Karstrup et al 1993, Ulitzsch et al 2004, Eryilmaz et al 2005).

A number of complementary therapies for puerperal mastitis are available. These include herbal homeopathic options such as high-potency belladonna, Hepar sulph, Bellis perennis and Phytolacca (Barbosa-Cesnik et al 2003, Kvist et al 2007a). Midwives in Sweden use acupuncture needles placed at the heart 3, gallbladder 21, and spleen 6 (Kvist et al 2007b). They also use oxytocin nasal spray to improve the milk ejection reflex, which may have become distended from milk stasis (Kvist et al 2007).

Associated conditions include:

Non-Lactational Infections

These infections can be grouped into peripheral or periareolar. Periareolar infections are seen in young women, and are often secondary to periductal mastitis (associated with cigarette smoking) (Schafer et al 1988, Bundred et al 1993). It is thought that particulates in cigarette smoke may indirectly or directly damage the wall of the subareolar ducts. Metabolites such as epoxides, nicotine, cotinine and lipid peroxidise have been shown to accumulate in smokers within 15 min of a woman starting to breast feed (Petrakis et al 1980). Smoking may affect normal bacterial flora, leading to a proliferation of pathogenic aerobic and anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria. Microvascular changes may also lead to local ischaemia. Patients with periareolar inflammation often present with a mass. Very rarely, the infection is due to underlying comedo necrosis in DCIS. It is advisable to perform a mammogram for all women over 35 years of age after resolution of the inflammation. The rate of recurrence is high for periareolar infections. Peripheral non-lactational breast abscesses are three times more common in premenopausal women than peri-/postmenopausal women. Some of these infections are most commonly caused by S. aureus and may be associated with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, exogenous steroid use and trauma.

All breast infections are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and clinical/ultrasound-guided drainage of any collections of pus (Hayes et al 1991). Aspiration has now become the standard of treatment superseding open drainage (Dixon 1988, 1992, O’Hara et al 1996). Patients should be reviewed every 2–3 days and any further collections aspirated. Periareolar non-lactational abscesses can be treated by repeated aspiration; however, persistent abscesses are common. Mammary duct fistula occurs in one-third of patients following incision and drainage of periareolar abscesses (Bundred et al 1987). These are definitively managed by excising the entire fistula tract with primary closure and antibiotic cover. Laying open of a mammary fistula leaves an unsightly scar across the nipple.

HIV infections

Immunocompromised patients (men and women) are particular susceptible to breast infections.

Granulomatous mastitis

Granulomatous mastitis is a rare condition characterized by non-caseating granulomas and microabscesses confined to a breast lobule. Patients may present with recurrent/multiple abscesses or a hard, tender mass. Granulomatous mastitis occurs most commonly in parous, young women. Many different organisms can cause granulomatous mastitis, but a recent study isolated corynebacteria in nine out of 12 women with the condition (Erhan et al 2000, Paviour et al 2002, Diesing et al 2004). This condition is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Tuberculosis of the breast

Tuberculous mastitis is a rare breast condition in which the clinical and radiological features can be easily confused with carcinoma or pyogenic breast abscess. Diagnosis is based on identification of typical histological features under microscopy or the detection of tubercule bacilli (Tewari and Shukla 2005).

Foreign body reactions

Silicone and paraffin, both used in breast augmentation and reconstructive surgery, can cause a granulomatous reaction in the breast. Silicone granulomas (siliconomas) usually occur following direct injection of silicone into the breast tissue or following an extracapsular rupture of a silicone implant (van Diest et al 1998). Fibrosis and contraction may lead to the development of firm, tender nodules in the breast.

Recurring subareolar abscess (Zuska’s disease)

This is a rare bacterial infection characterized by a triad of: (1) draining cutaneous fistula, (2) chronic, thick discharge from the nipple, and (3) recurrent mammary abscess (Passaro et al 1994). This is caused by squamous metaplasia of one or more lactiferous ducts, often induced by smoking. Keratin plugs obstruct and dilate the proximal duct, resulting in infection and rupture. An abscess may form which requires complete excision of the affected duct and the sinus tract for successful treatment.

Mastitis of infancy

Peak occurrence is reported between the second and fifth weeks of life (Rudoy and Nelson 1975, Walsh and McIntosh 1986, Efrat et al 1995, Stricker et al 2005). Females are more often involved than males (ratio 3.5:1). A possible explanation for the predominance of females is the tendency of breast hypertrophy in female newborns to persist longer than in males. The majority of cases are caused by S. aureus. The choice of antibiotic should be guided by Gram stain when possible, and otherwise should consist of an agent effective against S. aureus which is responsible for most cases. All patients require close monitoring for progression, and whilst there is no optimal duration of treatment, one study required treatment of patients for no longer than 14 days. In the case of abscess formation, incision and drainage under general anaesthetic combined with antibiotics is indicated.

Benign Neoplasms of the Breast

Adenoma

Adenoma is a pure epithelial neoplasm of the breast, and is subdivided into tubular, lactating, apocrine, ductal and pleomorphic adenomas. Lactating and tubular adenomas are more common in women of reproductive age. Lactating adenoma is the most common breast mass during pregnancy and puerperium, presenting as a solitary/multiple, discrete, palpable mobile mass, often less than 3 cm in size. The lesion is well circumscribed and lobulated, and acini are lined with actively secreting cuboidal cells. Lactating adenoma can occur in areas such as the axilla, chest wall or vulva (Reeves and Tabuenca 2000, Baker et al 2001). The tumour does not generally recur locally and there is no evidence of malignant potential.

Tubular adenoma of the breast (pure adenoma) presents as a solitary, well-circumscribed, firm mass. Radiologically, it may resemble a calcified fibroadenoma (Soo et al 2000). Lactating and tubular adenomas can be distinguished from fibroadenomas by the presence of scant stroma in the former.

Nipple adenoma

Nipple adenoma is a benign tumour that can clinically mimic Paget’s disease. It presents as a discrete, palpable tumour of the papilla of the nipple. Nipple erosion and discharge are usually observed. It is treated by excision biopsy, but recurrences have been reported in incompletely excised lesions (Montemarano et al 1995).

Hamartoma

Hamartoma is an uncommon lesion also known as a ‘fibroadenolipoma’, ‘lipofibroadenoma’ or ‘adenolipoma’, consisting of varying amounts of glandular, adipose and fibrous tissue. Clinically, a hamartoma may present as a painless, discrete encapsulated mass, and although the pathogenesis is not certain, it is thought to develop as a result of dysgenesis. Mammographically, it is well circumscribed, consisting of both lipomatous and soft tissue elements (Herbert et al 2002, Gatti et al 2005). Histologically, the appearance is of normal breast and fat tissue distributed in a nodular fashion within a fibrotic stroma that extends between individual lobules and destroys the normal interlobular specialized loose stroma (Tse et al 2002). Hamartomas are managed by surgical excision.

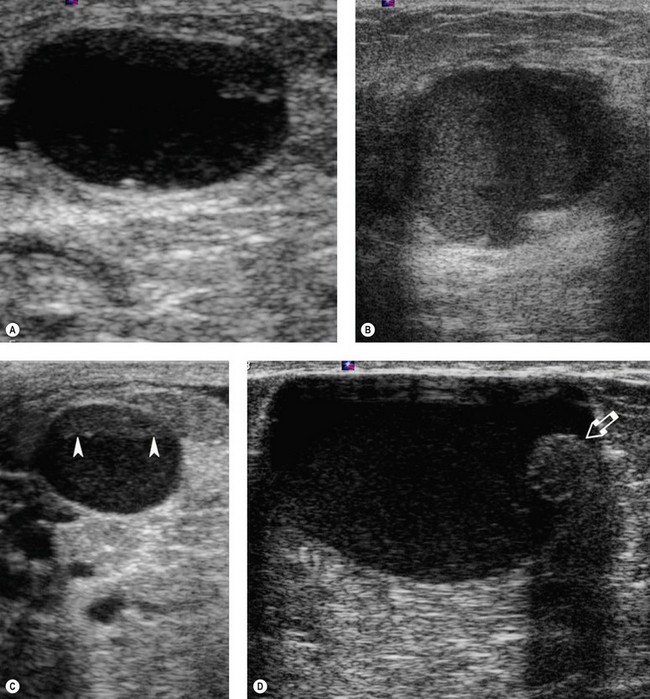

Lipoma

Lipoma of the breast is a benign, often solitary tumour composed of mature fat cells that tends to present in the fifth decade. Clinically, it may present as a well-circumscribed, smooth or lobulated mass that is soft and non-tender. Imaging shows a radiolucent mass on mammography and either normal or echogenic fat on ultrasonography (Figure 46.6), and FNAC often reveals fat cells with or without normal epithelial cells. If the diagnosis is uncertain, surgical excision is recommended (Lanng et al 2004). Liposarcoma of the breast is very rare (Blanchard et al 2003). Pseudolipoma of the breast may present clinically as a lipoma, but is actually a small cancer that produces compressed fat lobules as the suspensory ligaments of the breast shorten.

Granular cell tumour

This is an uncommon benign tumour that arises from the Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system. It occurs frequently in the head and neck (particularly the oral cavity), and occurs in the breast in 5–6% of cases (Montagnese et al 2004). Clinically and mammographically, it can mimic carcinoma (Ilvan et al 2005). These tumours are generally small (<3 cm) and well circumscribed; however, in some cases, infiltrative margins have been reported. S100 immunostaining supports the derivation of this tumour from Schwann cells (Balzan et al 2001). Most granular cell tumours are benign, but some malignant cases have been reported. Suspicious features for malignancy include size over 5 cm, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, presence of necrosis and local recurrence (Adeniran et al 2004). These tumours are treated with wide local excision, with incomplete margins resulting in local recurrence.

Other Breast Masses

Fat necrosis

Fat necrosis is a benign non-suppurative inflammatory condition affecting the adipose tissue of the breast. It can occur secondary to trauma (accidental/surgical) or may be associated with carcinoma, duct ectasia and fibrocystic disease. Clinically, it can mimic carcinoma if it appears as an ill-defined or dense speculated mass, associated with skin retraction (Kinoshita et al 2002). Imaging may not always be able to distinguish between fat necrosis and carcinoma (Pullyblank et al 2001). Excision biopsy is required if malignancy cannot be excluded on needle core biopsy.

Lymph nodes

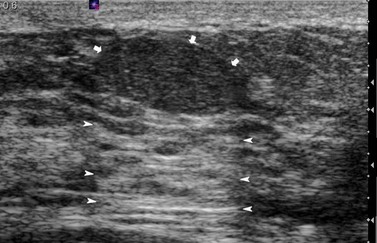

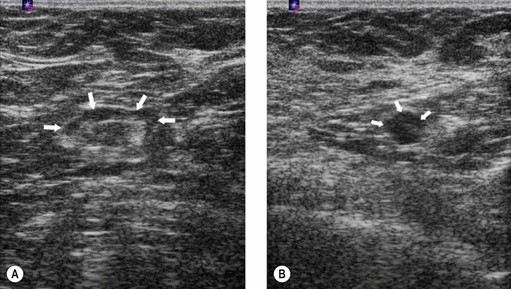

Lymph nodes may be isoechoic with the surrounding fat in a mainly fatty breast. They usually have an oval shape, with a slightly more translucent cortex and a slightly increased echogenic medulla (Figure 46.7). The vessels entering the hilum of the cortex can frequently be demonstrated with the aid of colour Doppler. Reactive, hypertrophied lymph nodes retain their anatomical structure and appearance, whereas lymph nodes that have been invaded by the tumour from a breast primary are usually masses of reduced echogenicity, often with a similar echogenicity to the tumour. As in other parts of the body, it is not always possible to exclude the presence of tumour from a node which appears to be hypertrophied with a normal architecture.

KEY POINTS

Acs G, Simpson JF, Bleiweiss IJ, et al. Microglandular adenosis with transition into adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2003;27:1052-1060.

Adeniran A, Al-Ahmadie H, Mahoney MC, Robinson-Smith TM. Granular cell tumor of the breast: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. The Breast Journal. 2004;10:528-531.

Agoff SN, Lawton TJ. Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia: can we accurately predict benign behavior from core needle biopsy? American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004;122:440-443.

Ali-Fehmi R, Carolin K, Wallis T, Visscher DW. Clinicopathologic analysis of breast lesions associated with multiple papillomas. Human Pathology. 2003;34:234-239.

Amir L. Breastfeeding and Staphylococcus aureus: three case reports. Breastfeeding Review. 2002;10:15-18.

Amir LH, Pakula S. Nipple pain, mastalgia and candidiasis in the lactating breast. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;31:378-380.

Amir LH, Forster D, Mclachlan H, Lumley J. Incidence of breast abscess in lactating women: report from an Australian cohort. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111:1378-1381.

Baker TP, Lenert JT, Parker J, et al. Lactating adenoma: a diagnosis of exclusion. The Breast Journal. 2001;7:354-357.

Balzan SM, Farina PS, Maffazzioli L, Riedner CE, Guedes Neto EP, Fontes PR. Granular cell breast tumour: diagnosis and outcome. European Journal of Surgery. 2001;167:860-862.

Baratelli GM, Riva C. Diabetic fibrous mastopathy: sonographic–pathologic correlation. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2005;33:34-37.

Barbosa-Cesnik C, Schwartz K, Foxman B. Lactation mastitis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:1609-1612.

Bartow SA, Pathak DR, Black WC, Key CR, Teaf SR. Prevalence of benign, atypical, and malignant breast lesions in populations at different risk for breast cancer. A forensic autopsy study. Cancer. 1987;60:2751-2760.

Bazzocchi F, Santini D, Martinelli G, et al. Juvenile papillomatosis (epitheliosis) of the breast. A clinical and pathologic study of 13 cases. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1986;86:745-748.

Bedinghaus JM. Care of the breast and support of breast-feeding. Primary Care. 1997;24:147-160.

Beischer NA, Hueston JH, Pepperell RJ. Massive hypertrophy of the breasts in pregnancy: report of 3 cases and review of the literature, ‘never think you have seen everything’. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 1989;44:234-243.

Blanchard DK, Reynolds CA, Grant CS, Donohue JH. Primary nonphyllodes breast sarcomas. American Journal of Surgery. 2003;186:359-361.

Blommers J, De Lange-De Klerk ES, Kuik DJ, Bezemer PD, Meijer S. Evening primrose oil and fish oil for severe chronic mastalgia: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;187:1389-1394.

Bundred NJ, Dixon JM, Chetty U, Forrest AP. Mammillary fistula. British Journal of Surgery. 1987;74:466-468.

Bundred NJ, Dover MS, Aluwihare N, Faragher EB, Morrison JM. Smoking and periductal mastitis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1993;307:772-773.

Caleffi M, Filho DD, Borghetti K, et al. Cryoablation of benign breast tumors: evolution of technique and technology. Breast. 2004;13:397-407.

Camuto PM, Zetrenne E, Ponn T. Diabetic mastopathy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Archives of Surgery. 2000;135:1190-1193.

Carter BA, Page DL, Schuyler P, et al. No elevation in long-term breast carcinoma risk for women with fibroadenomas that contain atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 2001;92:30-36.

Castro CY, Whitman GJ, Sahin AA. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia of the breast. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;25:213-216.

Cole P, Mark Elwood J, Kaplan SD. Incidence rates and risk factors of benign breast neoplasms. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;108:112-120.

Cook MG, Rohan TE. The patho-epidemiology of benign proliferative epithelial disorders of the female breast. Journal of Pathology. 1985;146:1-15.

De Wilde JP, Rivers AW, Price DL. A review of the current use of magnetic resonance imaging in pregnancy and safety implications for the fetus. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2005;87:335-353.

Devereux WP. Acute puerperal mastitis. Evaluation of its management. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1970;108:78-81.

Diesing D, Axt-Fliedner R, Hornung D, Weiss JM, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Granulomatous mastitis. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2004;269:233-236.

Dixon J. ABC of Breast Diseases. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1994.

Dixon JM. Repeated aspiration of breast abscesses in lactating women. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1988;297:1517-1518.

Dixon JM. Outpatient treatment of non-lactational breast abscesses. British Journal of Surgery. 1992;79:56-57.

Dixon JM, Mcdonald C, Elton RA, Miller WR. Risk of breast cancer in women with palpable breast cysts: a prospective study. Edinburgh Breast Group. The Lancet. 1999;353:1742-1745.

Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312:146-151.

Dupont WD, Page DL. Relative risk of breast cancer varies with time since diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia. Human Pathology. 1989;20:723-725.

Dupont WD, Parl FF, Hartmann WH, et al. Breast cancer risk associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 1993;71:1258-1265.

Dupont WD, Page DL, Parl FF, et al. Long-term risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:10-15.

Efrat M, Mogilner JG, Iujtman M, Eldemberg D, Kunin J, Eldar S. Neonatal mastitis — diagnosis and treatment. Israel Journal of Medical Science. 1995;31:558-560.

Erhan Y, Veral A, Kara E, et al. A clinicopathologic study of a rare clinical entity mimicking breast carcinoma: idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast. 2000;9:52-56.

Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Hakan Tekelioglu M, Daldal E. Management of lactational breast abscesses. Breast. 2005;14:375-379.

Escobar PF, Crowe JP, Matsunaga T, Mokbel K. The clinical applications of mammary ductoscopy. American Journal of Surgery. 2006;191:211-215.

Espinosa LA, Daniel BL, Vidarsson L, Zakhour M, Ikeda DM, Herfkens RJ. The lactating breast: contrast-enhanced MR imaging of normal tissue and cancer. Radiology. 2005;237:429-436.

Eusebi V, Foschini MP, Betts CM, et al. Microglandular adenosis, apocrine adenosis, and tubular carcinoma of the breast. An immunohistochemical comparison. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1993;17:99-109.

Fetherston C. Characteristics of lactation mastitis in a Western Australian cohort. Breastfeeding Review. 1997;5:5-11.

Fitzgibbons PL, Henson DE, Hutter RV. Benign breast changes and the risk for subsequent breast cancer: an update of the 1985 consensus statement. Cancer Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 1998;122:1053-1055.

Foxman B, D’Arcy H, Gillespie B, Bobo JK, Schwartz K. Lactation mastitis: occurrence and medical management among 946 breastfeeding women in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:103-114.

Gatti G, Mazzarol G, Simsek S, Viale G. Breast hamartoma: a case report. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2005;89:145-147.

Gomez A, Mata JM, Donoso L, Rams A. Galactocele: three distinctive radiographic appearances. Radiology. 1986;158:43-44.

Greskovich JFJr, Macklis RM. Radiation therapy in pregnancy: risk calculation and risk minimization. Seminars in Oncology. 2000;27:633-645.

Guray M, Sahin AA. Benign breast diseases: classification, diagnosis, and management. The Oncologist. 2006;11:435-449.

Haagenson C. Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1986.

Haj M, Weiss M, Herskovits T. Diabetic sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis of the breast. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2004;18:187-191.

Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:229-237.

Hayes R, Michell M, Nunnerley HB. Acute inflammation of the breast — the role of breast ultrasound in diagnosis and management. Clinical Radiology. 1991;44:253-256.

Herbert M, Sandbank J, Liokumovich P, et al. Breast hamartomas: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical studies of 24 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41:30-34.

Houssami N, Irwig L, Ung O. Review of complex breast cysts: implications for cancer detection and clinical practice. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 2005;75:1080-1085.

Howard BA, Gusterson BA. Human breast development. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000;5:119-137.

Hughes LE, Mansel RE, Webster DJ. Aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI): a new perspective on pathogenesis and nomenclature of benign breast disorders. The Lancet. 1987;2:1316-1319.

Hutchinson WB, Thomas DB, Hamlin WB, Roth GJ, Peterson AV, Williams B. Risk of breast cancer in women with benign breast disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1980;65:13-20.

Ilvan S, Ustundag N, Calay Z, Bukey Y. Benign granular-cell tumour of the breast. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2005;48:155-156.

Ivan D, Selinko V, Sahin AA, Sneige N, Middleton LP. Accuracy of core needle biopsy diagnosis in assessing papillary breast lesions: histologic predictors of malignancy. Modern Pathology. 2004;17:165-171.

Jacklin RK, Ridgway PF, Ziprin P, Healy V, Hadjiminas D, Darzi A. Optimising preoperative diagnosis in phyllodes tumour of the breast. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2006;59:454-459.

Jacobs TW, Byrne C, Colditz G, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ. Radial scars in benign breast-biopsy specimens and the risk of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:430-436.

Jensen RA, Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW. Invasive breast cancer risk in women with sclerosing adenosis. Cancer. 1989;64:1977-1983.

Karstrup S, Solvig J, Nolsoe CP, et al. Acute puerperal breast abscesses: US-guided drainage. Radiology. 1993;188:807-809.

Katz SC, Hazen A, Colen SR, Roses DF. Poland’s syndrome and carcinoma of the breast: a case report. The Breast Journal. 2001;7:56-59.

Kennedy M, Masterson AV, Kerin M, Flanagan F. Pathology and clinical relevance of radial scars: a review. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2003;56:721-724.

Kinlay JR, O’Connell DL, Kinlay S. Incidence of mastitis in breastfeeding women during the six months after delivery: a prospective cohort study. Medical Journal of Australia. 1998;169:310-312.

Kinoshita T, Yashiro N, Yoshigi J, Ihara N, Narita M. Fat necrosis of breast: a potential pitfall in breast MRI. Clinical Imaging. 2002;26:250-253.

Kleer CG, Tseng MD, Gutsch DE, et al. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus in rapidly growing fibroadenomas of the breast in immunosuppressed hosts. Modern Pathology. 2002;15:759-764.

Kline TS, Lash SR. The bleeding nipple of pregnancy and postpartum period; a cytologic and histologic study. Acta Cytologica. 1964;8:336-340.

Koerner FC. Epithelial proliferations of ductal type. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 2004;21:10-17.

Krieger N, Hiatt RA. Risk of breast cancer after benign breast diseases. Variation by histologic type, degree of atypia, age at biopsy, and length of follow-up. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;135:619-631.

Kudva YC, Reynolds CA, O’Brien T, Crotty TB. Mastopathy and diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports. 2003;3:56-59.

Kvist LJ, Hall-Lord ML, Larsson BW. A descriptive study of Swedish women with symptoms of breast inflammation during lactation and their perceptions of the quality of care given at a breastfeeding clinic. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2007;2:2.

Kvist LJ, Hall-Lord ML, Rydhstroem H, Larsson BW. A randomised-controlled trial in Sweden of acupuncture and care interventions for the relief of inflammatory symptoms of the breast during lactation. Midwifery. 2007;23:183-195.

La Vecchia C, Parazzini F, Franceschi S, Decarli A. Risk factors for benign breast disease and their relation with breast cancer risk. Pooled information from epidemiologic studies. Tumori. 1985;71:167-178.

Lafreniere R. Bloody nipple discharge during pregnancy: a rationale for conservative treatment. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1990;43:228-230.

Lanng C, Eriksen BO, Hoffmann J. Lipoma of the breast: a diagnostic dilemma. Breast. 2004;13:408-411.

Lawrence RA. Breastfeeding. A Guide for the Medical Profession. St Louis: Mosby; 2005.

Lee KC, Chan JK, Gwi E. Tubular adenosis of the breast. A distinctive benign lesion mimicking invasive carcinoma. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1996;20:46-54.

Levshin V, Pikhut P, Yakovleva I, Lazarev I. Benign lesions and cancer of the breast. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 1998;7(Suppl 1):S37-S40.

Lewison EF, Jones GS, Trimble FH, da Lima LC. Gigantomastia complicating pregnancy. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1960;110:215-223.

Livingstone V, Stringer LJ. The treatment of Staphyloccocus aureus infected sore nipples: a randomized comparative study. Journal of Human Lactation. 1999;15:241-246.

Love SM, Gelman RS, Silen W. Sounding board. Fibrocystic ‘disease’ of the breast — a nondisease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;307:1010-1014.

MacGrogan G, Tavassoli FA. Central atypical papillomas of the breast: a clinicopathological study of 119 cases. Virchows Archiv: an International Journal of Pathology. 2003;443:609-617.

Mallon E, Osin P, Nasiri N, Blain I, Howard B, Gusterson B. The basic pathology of human breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000;5:139-163.

Marshall BR, Hepper JK, Zirbel CC. Sporadic puerperal mastitis. An infection that need not interrupt lactation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1975;233:1377-1379.

Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL, et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiology. Biomarkers and Prevention. 1997;6:297-301.

Mead PB. Infectious Protocols for Obstetrics and Gynecology. Montvale: Medical Economics Publishing; 1992.

Mercado CL, Naidrich SA, Hamele-Bena D, Fineberg SA, Buchbinder SS. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia of the breast: sonographic features with histopathologic correlation. The Breast Journal. 2004;10:427-432.

Montagnese MD, Roshong-Denk S, Zaher A, Mohamed I, StarenStaren ED. Granular cell tumor of the breast. The American Surgeon. 2004;70:52-54.

Montemarano AD, Sau P, James WD. Superficial papillary adenomatosis of the nipple: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1995;33:871-875.

Morel AS, Wu F, Della-Latta P, Cronquist A, Rubenstein D, Saiman L. Nosocomial transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from a mother to her preterm quadruplet infants. American Journal of Infection Control. 2002;30:170-173.

Muller J. Ueber den feineran Bau und die Forman der Krankhaften Geschwilste. Berlin: G Reimer; 1838.

Nagayama M, Watanabe Y, Okumura A, Amoh Y, Nakashita S, Dodo Y. Fast MR imaging in obstetrics. Radiographics. 2002;22:563-580. discussion 580–582

Nasser SM. Columnar cell lesions: current classification and controversies. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 2004;21:18-24.

Nielsen M, Christensen L, Andersen J. Radial scars in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 1987;59:1019-1025.

Noble WC. Skin bacteriology and the role of Staphylococcus aureus in infection. British Journal of. Dermatology. 1998;139(Suppl 53):9-12.

O’Callaghan MA. Atypical discharge from the breast during pregnancy and/or lactation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1981;21:214-216.

O’Hara RJ, Dexter SP, Fox JN. Conservative management of infective mastitis and breast abscesses after ultrasonographic assessment. British Journal of Surgery. 1996;83:1413-1414.

O’Malley FP, Bane AL. The spectrum of apocrine lesions of the breast. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2004;11:1-9.

Osei EK, Faulkner K. Fetal doses from radiological examinations. British Journal of Radiology. 1999;72:773-780.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. 1985;55:2698-2708.

Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, Dupont WD. Subsequent breast carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma. Cancer. 1996;78:258-266.

Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WDJr, Simpson JF. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2003;361:125-129.

Palli D, Rosselli Del Turco M, Simoncini R, Bianchi S. Benign breast disease and breast cancer: a case–control study in a cohort in Italy. International Journal of Cancer. 1991;47:703-706.

Passaro ME, Broughan TA, Sebek BA, Esselstyn CBJr. Lactiferous fistula. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1994;178:29-32.

Patterson JA, Scott M, Anderson N, Kirk SJ. Radial scar, complex sclerosing lesion and risk of breast cancer. Analysis of 175 cases in Northern Ireland. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2004;30:1065-1068.

Paviour S, Musaad S, Roberts S, et al. Corynebacterium species isolated from patients with mastitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:1434-1440.

Petrakis NL, Maack CA, Lee RE, Lyon M. Mutagenic activity in nipple aspirates of human breast fluid. Cancer Research. 1980;40:188-189.

Pinder SE, Ellis IO. The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) — current definitions and classification. Breast Cancer Research. 2003;5:254-257.

Pruthi S, Reynolds C, Johnson RE, Gisvold JJ. Tamoxifen in the management of pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia. The Breast Journal. 2001;7:434-439.

Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, Rayter Z. Fat necrosis of the female breast — Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391.

Qian JG, Wang XJ, Yu AR, Zhou FH. Surgical correction of axillary accessory breast tissue: 12 cases with emphasis on treatment option. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2008;61:968-970.

Ram AN, Chung KC. Poland’s syndrome: current thoughts in the setting of a controversy. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;123:949-953. discussion 954–955

Reeves ME, Tabuenca A. Lactating adenoma presenting as a giant breast mass. Surgery. 2000;127:586-588.

Rudoy RC, Nelson JD. Breast abscess during the neonatal period. A review. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1975;129:1031-1034.

Sabate JM, Clotet M, Torrubia S, et al. Radiologic evaluation of breast disorders related to pregnancy and lactation. Radiographics. 2007;27(Suppl 1):S101-S124.

Sandler TW, editor. Langman’s Medical Embroyology, 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2006;337-338.

Sarnelli R, Squartini F. Fibrocystic condition and ‘at risk’ lesions in asymptomatic breasts: a morphologic study of postmenopausal women. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;18:271-279.

Schafer P, Furrer C, Mermillod B. An association of cigarette smoking with recurrent subareolar breast abscess. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;17:810-813.

Schnitt SJ. The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: flat epithelial atypia — classification, pathologic features and clinical significance. Breast Cancer Research. 2003;5:263-268.

Schnitt SJ, Vincent-Salomon A. Columnar cell lesions of the breast. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2003;10:113-124.

Scott-Conner CEH. Diagnosing and managing breast disease during pregnancy and lactation. Medscape Women’s Health. 1997;2:1.

Shabtai M, Saavedra-Malinger P, Shabtai EL, et al. Fibroadenoma of the breast: analysis of associated pathological entities — a different risk marker in different age groups for concurrent breast cancer. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2001;3:813-817.

Son EJ, Oh KK, Kim EK. Pregnancy-associated breast disease: radiologic features and diagnostic dilemmas. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2006;47:34-42.

Soo MS, Dash N, Bentley R, Lee LH, Nathan G. Tubular adenomas of the breast: imaging findings with histologic correlation. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 2000;174:757-761.

Stricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Mastitis in early infancy. Acta Paediatrica. 2005;94:166-169.

Swelstad MR, Swelstad BB, Rao VK, Gutowski KA. Management of gestational gigantomastia. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118:840-848.

Talele AC, Slanetz PJ, Edmister WB, Yeh ED, Kopans DB. The lactating breast: MRI findings and literature review. The Breast Journal. 2003;9:237-240.

Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. A comparison of the results of long-term follow-up for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and intraductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer. 1990;65:518-529.

Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: diagnosis, clinical features & management. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2005;122:103-110.

Treves N, Sunderland DA. Cystosarcoma phyllodes of the breast: a malignant and a benign tumor; a clinicopathological study of seventy-seven cases. Cancer. 1951;4:1286-1332.

Tse GM, Law BK, Ma TK, et al. Hamartoma of the breast: a clinicopathological review. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002;55:951-954.

Ulitzsch D, Nyman MK, Carlson RA. Breast abscess in lactating women: US-guided treatment. Radiology. 2004;232:904-909.

van Diest PJ, Beekman WH, Hage JJ. Pathology of silicone leakage from breast implants. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1998;51:493-497.

Vargas HI, Vargas MP, Gonzalez KD, Eldrageely K, Khalkhali I. Outcomes of sonography-based management of breast cysts. American Journal of Surgery. 2004;188:443-447.

Vina M, Wells CA. Clear cell metaplasia of the breast: a lesion showing eccrine differentiation. Histopathology. 1989;15:85-92.

Vogel A, Hutchison BL, Mitchell EA. Mastitis in the first year postpartum. Birth. 1999;26:218-225.

Walsh M, McIntosh K. Neonatal mastitis. Clinical Pediatrics. 1986;25:395-399.

Webb JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK. The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation. European Radiology. 2005;15:1234-1240.

Wechselberger G, Schoeller T, Piza-Katzer H. Juvenile fibroadenoma of the breast. Surgery. 2002;132:106-107.

World Health Organization. Mastitis: Causes and Management. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

Wolf Y, Pauzner D, Groutz A, Walman I, David MP. Gigantomastia complicating pregnancy. Case report and review of the literature. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1995;74:159-163.