CHAPTER 116 Basic Principles of Skull Base Surgery

Historical Landmarks

Until the beginning of the 20th century, lesions located at the base of the skull were largely inoperable. Pioneers of different surgical areas started to envision and perform many of the significant approaches to the skull at the end of 19th century, and success was achieved in single cases. Classic examples are the suboccipital approach by Krause,1 transsphenoidal approaches to pituitary tumors introduced by Halstead,2 and the translabyrinthine route described by Panse.3 These techniques were then improved and became part of the routine armamentarium of the next generation of surgeons, including Cushing, Dandy, Guiot, Dott, Wüllstein, and Conley, among others.4 However, it was not until the mid-1960s that efforts to overcome interdisciplinary barriers led to further breakthroughs in skull base surgery and close cooperation among neurosurgeons, otorhinolaryngologists, and maxillofacial surgeons. The introduction of microsurgical techniques, advances in neuroanesthesiology, and new diagnostic tools such as high-resolution computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and superselective angiography were also essential.

Overview of Skull Base Surgery

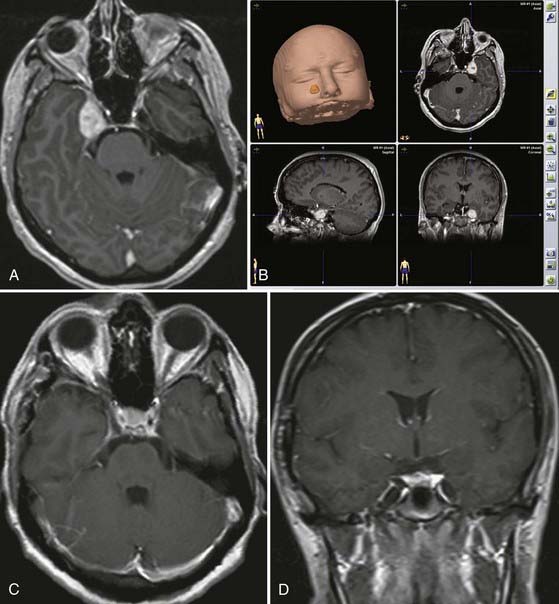

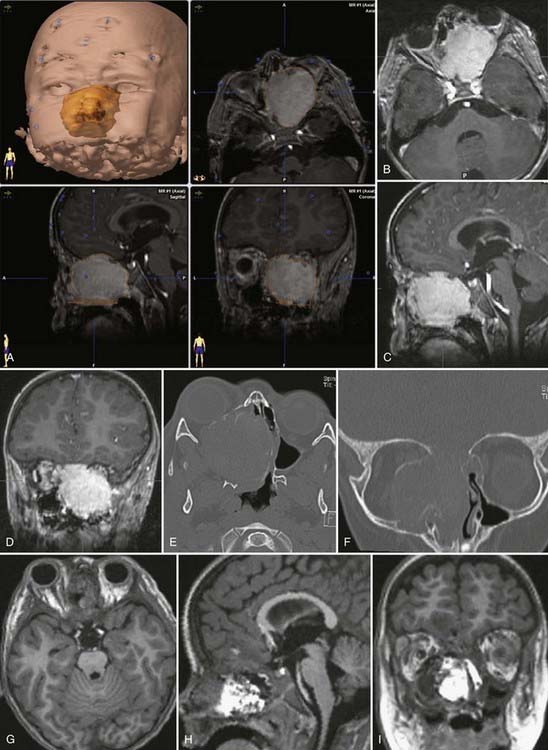

The second goal of skull base surgery involves the principle of drilling the skull base while avoiding major trauma to the brain. Experience with surgery on the skull base has shown the benefits of bone resection in reducing the need for brain retraction. Its indications have been expanded over the years to treat not only skull base–destroying lesions but also all intracranial lesions that can best be reached through the skull base. For example, some aneurysms of the basilar artery, although not true skull base lesions, are better attacked through transzygomatic or transpetrosal approaches, which involve minimal brain retraction and afford an enhanced view. High-speed drill techniques developed rapidly, and the drill has become a precise microsurgical instrument. Based on these principles, several approaches through the skull base were established, such as transfacial approaches, transpetrosal approaches, transcondylar approaches, and many others. The main goal of these techniques is to reduce the amount of brain retraction by means of bone resection, thus avoiding problems related to postoperative brain contusion and edema. Furthermore, the approach in itself should not be associated with significant procedure-related morbidity. Developments in computer technology and navigation devices have allowed online control of bony structures during the drilling procedure and tumor resection.5–9 Moreover, navigation may be used for localizing displaced or encased vessels, as well as for assessing tumor extension and its relationship to main landmarks (Fig. 116-1).

![]() Over the past decade the endoscope has become a widespread supplement to traditional skull base techniques, whether used in addition to the microscope or as the only visualizing tool.10–12 It provides a panoramic multi-angled view of the entire operative field. Freehand use of the endoscope allows a close-up view of the target area, and angled endoscopes enable one to see “around the corner“ (Video 116-1).

Over the past decade the endoscope has become a widespread supplement to traditional skull base techniques, whether used in addition to the microscope or as the only visualizing tool.10–12 It provides a panoramic multi-angled view of the entire operative field. Freehand use of the endoscope allows a close-up view of the target area, and angled endoscopes enable one to see “around the corner“ (Video 116-1).

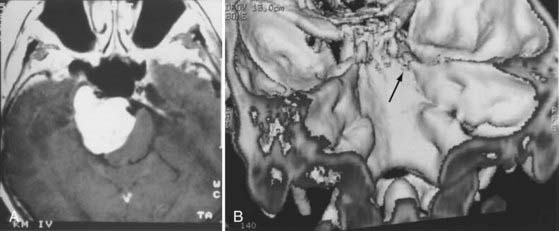

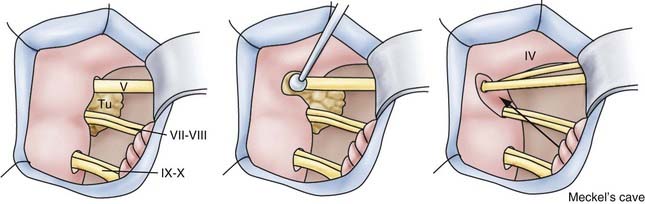

Trigeminal schwannoma—endoscopically assisted retrosigmoid suprameatal approach.

The retrosigmoid suprameatal approach was selected.

The schwannoma is initially debulked and dissected from the neural branches.

Complete tumor removal is accomplished. The uninvolved trigeminal branches are preserved.

Our years of experience in treating skull base lesions have allowed us to recognize a number of cases in which the use of extensive skull base procedures does not improve the surgical result and may in fact endanger it. In particular cases, extensive skull base approaches may significantly increase the risk for postoperative deficits. We are now past the era of enthusiastic resection of skull base lesions, and simple cranial approaches are again gaining popularity. Thus, some simple approaches, such as the retrosigmoid approach to the cerebellopontine angle, have proved to be most favorable for tumors in that location. In other cases, however, the approach has to be selected individually and always tailored to the characteristics of the particular tumor, its location, and the patient’s expectations.13

Surgery on the Anterior Skull Base

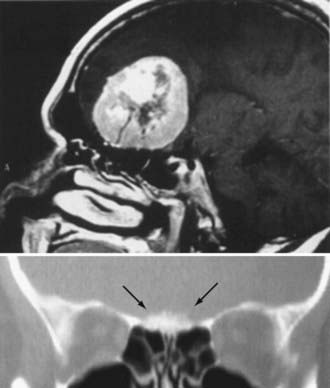

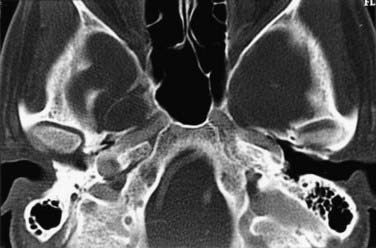

Different lesions may involve the anterior skull base, such as benign or malignant tumors, vascular lesions, maldevelopmental diseases, and trauma. Meningiomas of the olfactory groove and planum sphenoidale are the most frequent benign tumors encountered at the anterior skull base (Fig. 116-2).4,14 Adenocarcinomas and esthesioneuroblastomas are typical examples of malignant tumors that arise from the paranasal sinuses and secondarily involve the anterior skull base (Fig. 116-3). Fibrous dysplasia develops very slowly but may achieve a large size before it becomes symptomatic (Fig. 116-4). Other non-neoplastic lesions of the anterior cranial base include frontal encephaloceles and skull base trauma. Each of these lesions needs a particular treatment strategy. The surgeon must be familiar with the normal surgical anatomy of the skull base to understand the changes caused by these lesions and to manage them properly.

FIGURE 116-4 Fibrous dysplasia with extensive involvement of the anterior skull base on the left side.

Operative Anatomy of the Anterior Skull Base

From the endocranial view, the anterior cranial base has a flat surface that comprises the anterior border of the sphenoid wings and the roof of the orbita laterally and the planum sphenoidale medially (Fig. 116-5). In the middle, in varying prominence and height are the crista galli and the ethmoid plate. The dura in the medial portion at the area of the cribriform plate is more closely adherent to the skull base than in the lateral position. Depending on the degree of pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses, the size of the contact area between the paranasal sinuses and the anterior skull base may vary.15,16

The ethmoid cells form the lateral boundary of the contents of the orbita at the level of the skull base (Fig. 116-6). Medially, the lamina cribrosa constitutes the upper limit of the paranasal sinuses, and it is divided by the nasal septum. Behind are the two portions of the sphenoidal sinus. These portions vary in size, as do the other paranasal sinuses. Figure 116-7 shows the relationship of the sphenoidal sinus to the sella and its contents, along with the surrounding structures.

FIGURE 116-6 Axial section through the anterior skull base at the level of the orbits and ethmoidal sinus.

Extracranial Approach to the Anterior Skull Base

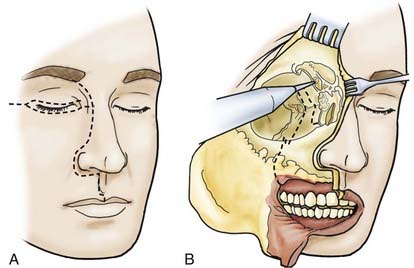

Extracranial Approach with Unilateral Orbital Exenteration

The skin incision is extended, in accordance with extension of the tumor, paranasally toward the upper lip. If necessary, the lip is split (Fig. 116-8). The stepped incision produces a favorable aesthetic result. With ethmoidal tumors, depending on the extent of involvement of the medial edge and orbit, a decision must be made whether the upper and lower lids have to be resected or only the skin near the edge needs to be sacrificed. In the latter case, the upper and lower lids can be used as tissue for epithelialization of the remaining orbita. The extent of freeing the soft cheek tissues is determined by the extension of the tumor.

To guard against infection, the remainder of the field should be covered with cotton patties before the dura is incised. If the basal craniectomy extends far anteriorly, the superior sagittal sinus is ligated and cut. To continue, the dura is resected step by step while pulling it caudally to avoid injury to brain structures. The incision is started at the anterior limit of the craniectomy so that resection of the dura on one or both sides can proceed to provide a clear view of the base of the frontal lobe. The resected piece of dura is marked and sent for serial histologic examination. The resulting dural defect is patched with fascia lata tucked between the bone and dural margins. The graft is additionally secured with a few anchoring sutures and fibrin glue. After the graft has been covered with silicone film, epithelialization of the lyophilized dura or the fascia lata occurs relatively quickly from the remaining mucosal rim. In a few weeks, the initially loose or sagging dural transplant changes into a firm, flat sheet of scar tissue. If resection of the anterior skull base extends beyond the fovea ethmoidalis and cribriform plate, a horizontal forehead and scalp flap conforming to the size of the cranial defect should be folded over to provide stable coverage of the duraplasty and epithelialization of the remaining orbital roof and fovea. The donor area of the scalp flap can be covered either with a split-thickness skin graft or by advancing other scalp flaps (Fig. 116-9).

Intracranial Approach to the Anterior Skull Base

Transfrontal Extradural Approach

Depending on the extent of the lesion, a bitemporal coronal incision is made, and a unilateral or bifrontal craniotomy is performed. The extent of the latter depends on the site of the tumor. With midline lesions, the dura is mobilized on both sides of the crista galli and in part is sharply elevated from the cribriform plate. If necessary, the dura can be detached bilaterally as far as the lower sphenoid wing and tuberculum sellae (Fig. 116-10). With this maneuver, clear delineation of the anterior skull base is possible. This approach also permits good exposure of the frontal sinus, ethmoid cells, and sphenoidal sinus, supplemented if necessary by removal of the crista galli itself. This method also offers good exposure of the optic canal and the superior aspect of the orbital contents. The optic chiasm with the intradural portion of the optic nerve is not visualized with this approach. Lesions extending to the clivus are accessible by dissecting along the posterior wall of the sphenoidal sinus or the anterior wall of the sella. The endocranium is sealed off from the paranasal sinus system with a dural or fascial transplant—in some cases with a galea-periosteal flap that has a basal pedicle (Fig. 116-11).

Transfrontal Intradural Approach

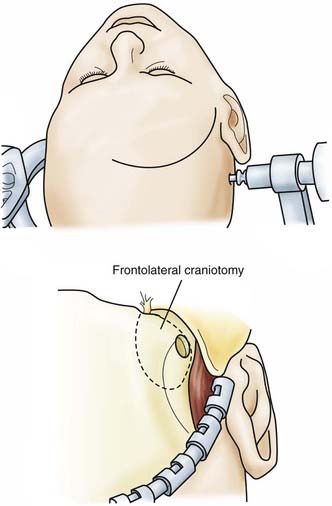

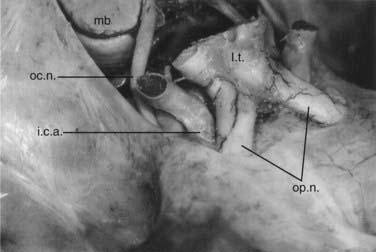

![]() For the frontolateral approach, the patient is positioned supine with the trunk elevated; the head is turned 10 degrees to the contralateral side, extended 15 to 20 degrees, and fixed in a Mayfield head holder. The frontolateral approach starts with a frontotemporal incision (usually on the right side) in front of the tragus, following just behind the hairline up to the midline (Fig. 116-12). A small craniotomy flap is created on one side close to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The dura is opened with a frontobasal incision. The arachnoid cisterns are opened progressively as the frontal lobe is gently retracted. Both optic nerves are exposed, along with the internal carotid artery (Fig. 116-13). Indications for the frontolateral approach include olfactory meningiomas, meningiomas of the planum sphenoidale and anterior clinoid, and suprasellar tumors such as meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and pituitary adenomas, among others (Video 116-2).

For the frontolateral approach, the patient is positioned supine with the trunk elevated; the head is turned 10 degrees to the contralateral side, extended 15 to 20 degrees, and fixed in a Mayfield head holder. The frontolateral approach starts with a frontotemporal incision (usually on the right side) in front of the tragus, following just behind the hairline up to the midline (Fig. 116-12). A small craniotomy flap is created on one side close to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The dura is opened with a frontobasal incision. The arachnoid cisterns are opened progressively as the frontal lobe is gently retracted. Both optic nerves are exposed, along with the internal carotid artery (Fig. 116-13). Indications for the frontolateral approach include olfactory meningiomas, meningiomas of the planum sphenoidale and anterior clinoid, and suprasellar tumors such as meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and pituitary adenomas, among others (Video 116-2).

Frontolateral approach—giant suprasellar meningioma.

A 50-year-old woman was evaluated for treatment of a giant suprasellar and parasellar meningioma.

A frontolateral approach was performed on the right side.

At the end the capsule is dissected from branches of the anterior cerebral artery and removed.

Surgery on the Middle and Posterior Skull Base

Operative Anatomy of the Parasellar Area and Cavernous Sinus

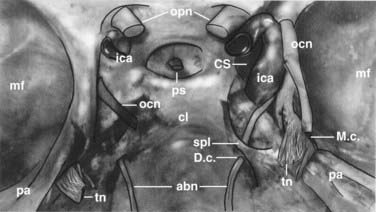

The parasellar area is limited by the optic nerves and optic chiasm anteriorly, the dorsum sellae posteriorly, and the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus laterally (Fig. 116-14). Cranial nerves III, IV, V1, and V2 lie between the two layers of dura forming the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. The outer layer is thicker than the inner layer. The medial periosteal layer rests against the sphenoid bone. After leaving its long intracisternal segment, the abducens nerve passes below the sphenopetrous ligament, which forms a narrow fibrous canal (Dorello’s canal). Cranial nerve VI and the internal carotid artery run for a certain distance within the cavernous sinus. Depending on the origin of the tumor, a certain pattern of displacement of the neurovascular structures can be expected. The goals of surgery for tumors of the parasellar region, particularly meningiomas, depend on the type of tumor growth. Tumors that grow in globular fashion and displace the surrounding structures can be completely resected with good outcome. In contrast, meningiomas that grow en plaque frequently show tight encasement of important neurovascular structures and cannot be completely resected without producing neurological deficits. Diffuse invasion of the basal dura, cavernous sinus, bone, and neuroforamina makes surgical cure impossible. In these cases, resection of the globular part of the tumor for decompression of neural tissues is the surgical goal.

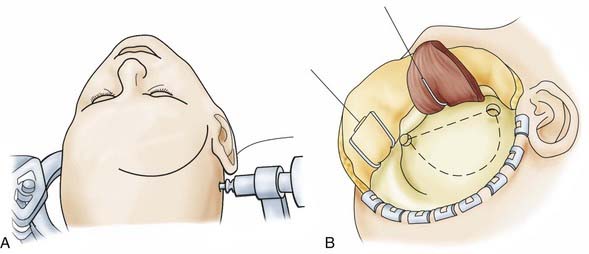

![]() Parasellar tumors are usually accessed through a frontolateral approach (see earlier) or with a frontotemporal (pterional) craniotomy,14,17–19 with or without unroofing the orbit.20 We usually keep the orbit intact in these approaches. For the frontotemporal approach (Video 116-3), the patient is placed in the supine position, and the head is turned about 30 degrees to the opposite side, slightly directed toward the floor and fixed in a Mayfield head holder system. The skin incision begins in front of the tragus and is extended to the midline in a curvilinear fashion, always behind the hairline (Fig. 116-15). Care is taken to preserve the facial nerve branch to the frontalis muscle. The temporal muscle is retracted inferiorly. The first bur hole is placed at the frontozygomatic angle. Centered in the pterion, the bone flap is cut with an electric craniotome. Under microscopic visualization, the dura is opened in a curvilinear fashion, and the sylvian fissure is dissected. The frontal lobe is slightly elevated and separated from the temporal lobe. Both are held by self-retractors. After identification of the vascular and neuronal structures in the region, the tumor mass is debulked as much as possible with ultrasonic aspiration. Using microsurgical technique, the tumor is carefully dissected from the anatomic elements. After removal of the tumor, hemostasis is ensured, and the dura is closed.

Parasellar tumors are usually accessed through a frontolateral approach (see earlier) or with a frontotemporal (pterional) craniotomy,14,17–19 with or without unroofing the orbit.20 We usually keep the orbit intact in these approaches. For the frontotemporal approach (Video 116-3), the patient is placed in the supine position, and the head is turned about 30 degrees to the opposite side, slightly directed toward the floor and fixed in a Mayfield head holder system. The skin incision begins in front of the tragus and is extended to the midline in a curvilinear fashion, always behind the hairline (Fig. 116-15). Care is taken to preserve the facial nerve branch to the frontalis muscle. The temporal muscle is retracted inferiorly. The first bur hole is placed at the frontozygomatic angle. Centered in the pterion, the bone flap is cut with an electric craniotome. Under microscopic visualization, the dura is opened in a curvilinear fashion, and the sylvian fissure is dissected. The frontal lobe is slightly elevated and separated from the temporal lobe. Both are held by self-retractors. After identification of the vascular and neuronal structures in the region, the tumor mass is debulked as much as possible with ultrasonic aspiration. Using microsurgical technique, the tumor is carefully dissected from the anatomic elements. After removal of the tumor, hemostasis is ensured, and the dura is closed.

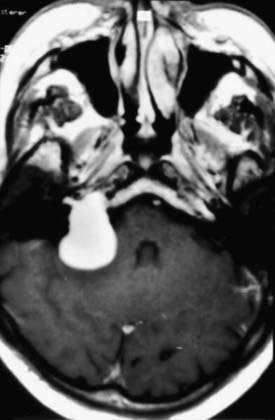

Tumor in the cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave.

The frontotemporal approach was selected.

Operative Anatomy of the Petrous Bone

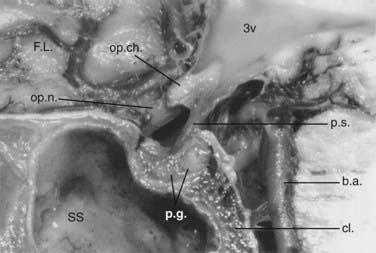

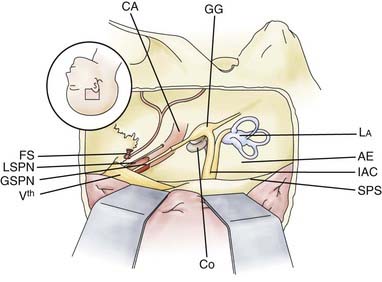

Key anatomic points in anterior approaches to the middle fossa include the foramen spinosum with the middle meningeal artery anteriorly; the arcuate eminence posteriorly; the petrous carotid artery, which is only partially covered by thin bone; and the superior petrosal sinus, which runs along the medial border of the upper surface of the petrous bone (Fig. 116-16). The greater petrosal nerve passes below the lateral margin of the trigeminal ganglion. Drilling along the course of the greater petrosal nerve in a dorsal direction exposes the geniculate ganglion, which can be followed in a medial direction to expose the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve up to its course into the internal auditory canal.16,17

The bony area between the greater petrosal nerve anteriorly, the carotid artery and the cochlea laterally, and the internal auditory canal and the semicircular canals posteriorly has been called Kawase’s triangle.18 Bone removal at that area exposes the prepontine area. A better view is achieved by transecting the tentorium (Fig. 116-17).

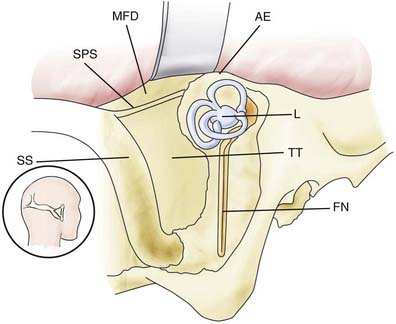

Decortication of the mastoid and removal of most mastoid air cells expose the middle fossa plate and the superior petrosal sinus superiorly, the anterior portion of the sigmoid sinus posteriorly, and the plate covering the labyrinth block and facial nerve anteriorly (Fig. 116-18). The lateral semicircular canal runs perpendicular to the facial nerve, and the posterior semicircular canal runs parallel to the sigmoid sinus. Anterior to the labyrinth block is the antrum and the digastric ridge. Complete bone removal in this area gives access to the cerebellopontine angle from the lateral direction.

Removal of bone behind the sigmoid sinus and inferior to the transverse sinus exposes the edge of both sinuses. Mastoid air cells and emissary veins running to the sigmoid sinus are frequently found in the mastoid bone close to the sinus. The retrosigmoid approach provides access to the cerebellopontine angle from the posterior direction (Fig. 116-19).

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Management

Symptoms and signs are related to the tumor’s location. Tumor locations can be divided into three main areas in relation to the internal auditory canal: anterior to, within, or posterior to it. Tumors arising within the internal auditory canal are more likely to produce hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, and more rarely, facial problems as early symptoms (Fig. 116-20). Tumors located anterior to the internal auditory canal may cause trigeminal symptoms (pain or hypoesthesia) and diplopia (sixth nerve). Tumors located posterior to the internal auditory canal may produce caudal cranial nerve disturbances such as dysphagia, hoarseness, and tongue atrophy. Not unusually, however, the tumor may remain asymptomatic until its growth reaches the internal auditory canal, at which point it results in hearing loss as the first symptom or cerebellar symptoms.

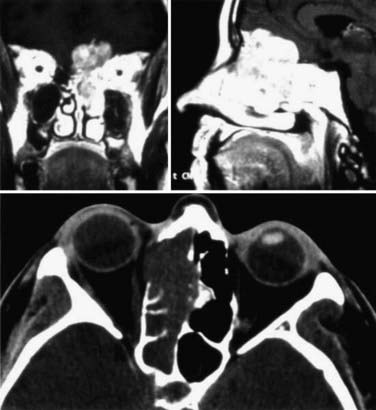

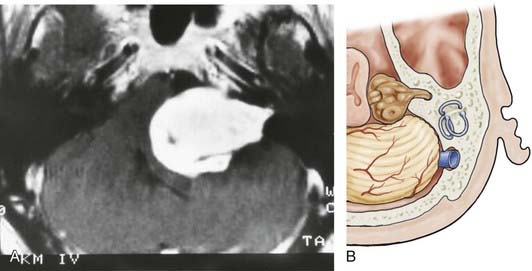

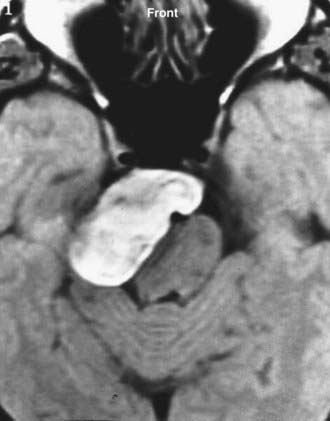

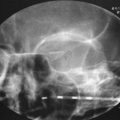

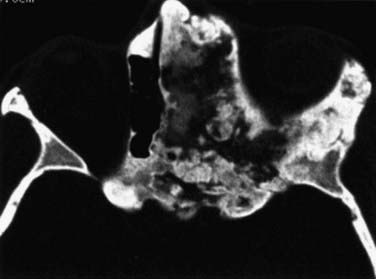

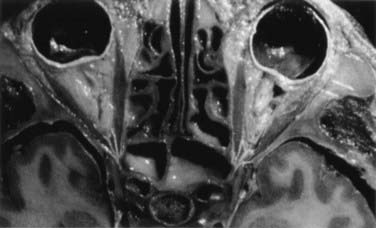

CT and MRI are complementary diagnostic tools in skull base surgery. High-resolution CT with bone algorithms provides an indispensable demonstration of bony landmarks (Fig. 116-21). MRI demonstrates the relationship between tumor and surrounding vascular and neural tissue (Fig. 116-22). Cerebral angiography shows tumor vascularization and the displacement and involvement of important vessels, and it provides the information needed for preoperative embolization.

Transpetrosal Approaches to the Middle and Posterior Skull Base

Skull base tumors arising from the area of the petrous bone may extend into the petroclival region, where they can destroy bony structures and compress the brainstem. Extension into the middle and posterior fossa occurs frequently, and involvement of the cavernous sinus is not rare. Surgical treatment of these tumors involves different approaches through the petrous bone. A number of transpetrosal approaches have been used by some authors.6,18–28 In recent years, however, partial or total petrosectomy has become very popular, and its indications have been extended. Because these approaches can result in a number of complications, including hearing loss, facial disturbances, and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, the indications for any kind of petrosectomy must be considered thoughtfully. Grossly, partial or total petrosectomy should be performed only if it is believed that it will facilitate tumor removal, increase surgical completeness, and improve outcome by increasing survival and reducing morbidity.

Middle Fossa Extradural Approach

This approach is indicated for extradural processes involving the petrous apex and upper clivus, such as chordomas and cholesteatomas (Fig. 116-23). It can also be used for intracanalicular acoustic neurinomas.

Approach to the Internal Auditory Canal

The patient’s head is positioned horizontal and slightly extended. A temporal craniotomy is performed anterior to the ear and above the zygoma. The dura is elevated from the floor of the middle fossa until the arcuate eminence and the greater petrosal nerve are visualized. Identification of the internal auditory canal involves drilling along the greater petrosal nerve, which exposes the geniculate ganglion.17 At this point, the drilling is turned medially to expose the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve until the fundus of the internal auditory canal is reached. Other techniques have been described to identify the internal auditory canal without exposure of the geniculate ganglion.

Approach to the Petroclival Region

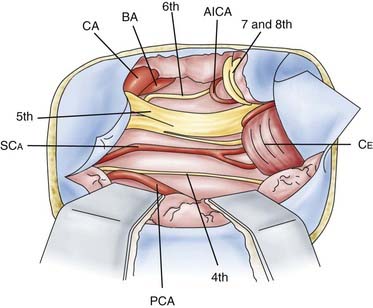

Anterior petrosal approaches involve extradural removal of the portion of the petrous apex situated between the greater petrosal nerve anteriorly, the carotid artery and cochlea laterally, and the labyrinth block posteriorly.18,29–31 The dura is then opened anterior to the seventh and eighth nerves. The view may be widened by dividing the tentorium. This approach gives a view of cranial nerves III to VIII, the basilar artery, the posterior cerebral artery, the superior cerebellar artery, and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Middle Fossa Intradural Approach

The subtemporal intradural transtentorial approach is indicated for tumors located in the petroclival area and within the petrous bone, for extension of tumor intradurally, and for brainstem displacement, such as caused by meningiomas, neurinomas (seventh nerve), and epidermoid tumors. It may also be indicated for basilar aneurysms.31 Advantages of this approach are a more anterior angle and widened visualization of the interpeduncular area, the basilar apex and upper trunk, the ventral lateral brainstem, and the upper petroclival area. The disadvantage is the potential for injury to important bridging veins running from the temporal lobe to the base of the skull.

Operative Technique

The dura around the petrous bone can be resected to perform a partial petrosectomy by drilling part of the petrous apex at Kawase’s triangle. Care should be taken to not injure the carotid artery and the cochlea. The exposure achieved with this approach is shown in Figure 116-16.

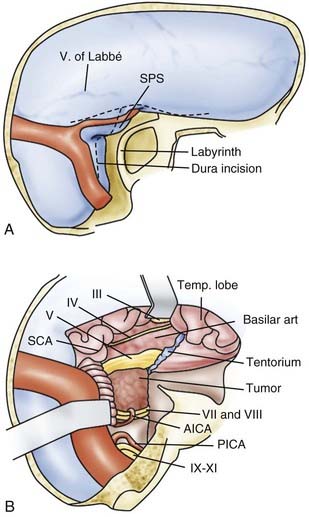

Posterior Fossa Extradural Approach

The so-called presigmoid (retrolabyrinthine) approach is used mostly in combination with a subtemporal approach for petroclival tumors that extend caudally up to the midclivus and supratentorially up to the medial middle fossa (Fig. 116-24).19,23,25,27,32,33 Vascular processes such as aneurysms of the upper and middle basilar artery can also be approached with this exposure. The major advantages of the presigmoid approach are less brain retraction and a shorter route to the petrous apex allowed by the bone removal. The major disadvantage is the potential for hearing and facial damage during bone drilling.27,34,35 For lesions that reach the lower clivus, the presigmoid approach can be combined with the retrosigmoid approach.36

FIGURE 116-24 Dumbbell-shaped trigeminal schwannoma with growth into the posterior and middle fossae.

Operative Technique

A temporal and suboccipital craniotomy is performed to expose the transverse and sigmoid sinuses. Using a high-speed air drill, a mastoidectomy is done, with exposure of the sigmoid sinus as low as the jugular bulb. Care is taken to not open the endolymphatic duct inside the endolymphatic aqueduct. The posterior wall of the petrous pyramid is drilled away in a lateral-medial direction as far anterior as possible without opening the posterior semicircular canal or the fallopian canal. The distance between the posterior semicircular canal and the anterior border of the sigmoid sinus varies from a few millimeters to 1 cm (see Fig. 116-18).

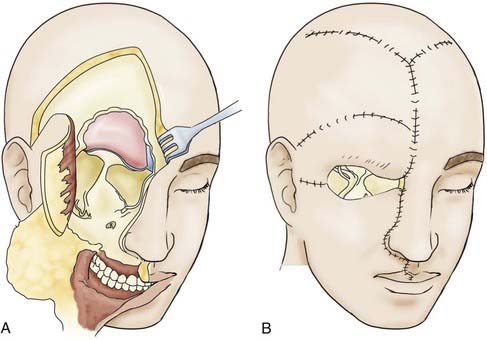

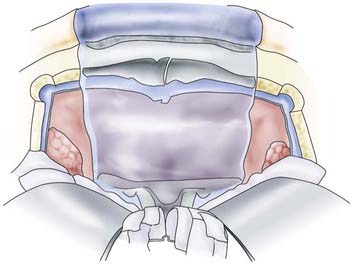

The dura is then cut in a T-shaped fashion (Fig. 116-25). The vein of Labbé is dissected from the cortical surface if necessary. The posterior temporal lobe is retracted superiorly. The superior petrosal sinus is ligated and divided. The tentorium is also cut in a lateral-medial direction anterior to the transverse sinus (and the vein of Labbé) and posterior to the area in which the trochlear nerve penetrates the edge of the tentorium. If the tentorial sinuses are causing significant bleeding, they can be packed with fibrin sponges. Bipolar coagulation should not be used to stop the bleeding because of the risk of injuring the fourth nerve during this procedure.

Posterior Fossa Intradural Approach

This approach is used mainly for tumors of the cerebellopontine angle extending to the lower clivus.35,37–41 The posterior lip of the internal auditory canal can be opened to allow exposure of the entire contents of the canal. Even some petroclival meningiomas that affect the supratentorial surface of the tentorium can be removed through this approach by resecting the tentorium from below.35,39,42

Operative Technique

For acoustic neurinomas, the posterior lip of the internal acoustic canal is drilled as a first step. Lateral tumor extension and the intracanalicular nerves are identified. Care is taken to not open the entire canal; the most lateral 2 mm of wall should be left in place to avoid opening the labyrinth. The depth of the remaining canal can be measured with a micro–nerve hook. If the labyrinth is entered accidentally, aspiration should be avoided at the opened area, and immediate closure is achieved with muscle and fibrin glue.43 The tumor is enucleated with the Cavitron ultrasonic aspirator and dissected away from the nerves and vessels while respecting the arachnoid sheath.

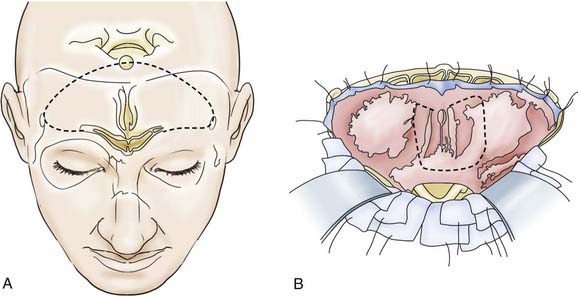

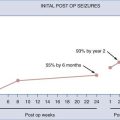

![]() For meningiomas, it makes a difference whether the tumor originates anterior or posterior to the internal auditory canal. Anterior meningiomas must be removed between the cranial nerves, mostly between the fifth and the seventh-eighth complex. Posterior meningiomas are debulked and reduced in size until the cranial nerves are identified. The technique of dissection of the arachnoid sheath is used for nerve and vessel preparation and preservation. Recently, tumors of the petroclival region (e.g., meningiomas, trigeminal schwannomas) have been removed by an extension of the retrosigmoid approach that we call the retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach.44 This approach is suitable for tumors located anterior to the internal auditory canal with extension through Meckel’s cave into the middle fossa (Fig. 116-26). After a retrosigmoid craniotomy and opening of the dura, the suprameatal approach includes drilling away the petrous bone located above and anterior to the internal auditory canal, thereby opening Meckel’s cave (Fig. 116-27). Even large petroclival tumors can be accessed by this approach (see Video 116-1).35

For meningiomas, it makes a difference whether the tumor originates anterior or posterior to the internal auditory canal. Anterior meningiomas must be removed between the cranial nerves, mostly between the fifth and the seventh-eighth complex. Posterior meningiomas are debulked and reduced in size until the cranial nerves are identified. The technique of dissection of the arachnoid sheath is used for nerve and vessel preparation and preservation. Recently, tumors of the petroclival region (e.g., meningiomas, trigeminal schwannomas) have been removed by an extension of the retrosigmoid approach that we call the retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach.44 This approach is suitable for tumors located anterior to the internal auditory canal with extension through Meckel’s cave into the middle fossa (Fig. 116-26). After a retrosigmoid craniotomy and opening of the dura, the suprameatal approach includes drilling away the petrous bone located above and anterior to the internal auditory canal, thereby opening Meckel’s cave (Fig. 116-27). Even large petroclival tumors can be accessed by this approach (see Video 116-1).35

Meningiomas of the craniocervical junction can be removed by combining the retrosigmoid approach with C1 hemilaminectomy.40 Resection of the posterior third of the condyle may be useful in some cases. In our experience, transcondylar approaches with extensive condyle removal are never necessary.

Neurinomas of the caudal cranial nerves in the region of the cerebellopontine angle extending up to the jugular foramen can also be resected with the retrosigmoid approach (Fig. 116-28). The jugular foramen is opened intradurally, and the tumor is removed.44 Major involvement of the jugular foramen requires a combined extradural cervical approach and partial mastoidectomy, with extradural opening of the jugular foramen and cervical exposure of the caudal cranial nerves, as described next.45,46

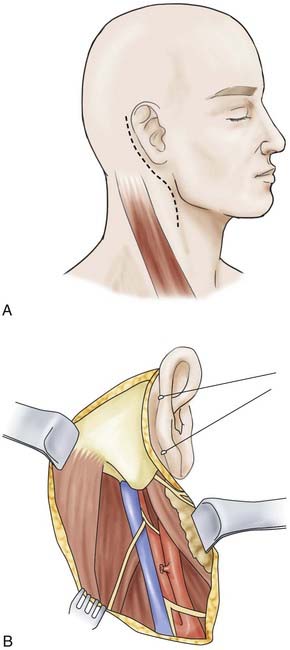

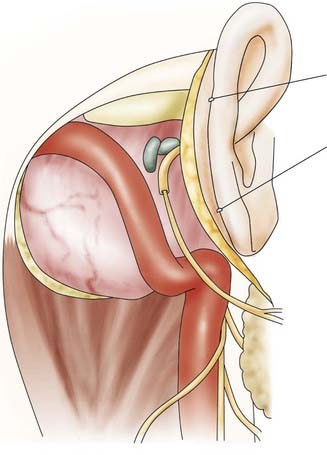

Combined Intradural-Extradural Approach to the Jugular Foramen

The patient is placed supine with the head turned 60 degrees to the contralateral side and slightly retroflected. The surgery involves three main steps: (1) exposure of the cervical region with vessels and nerves, (2) craniectomy and mastoidectomy, and (3) intradural exposure. After a retroauricular skin incision, a dissection plane is found between the parotid gland and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 116-29). The greater auricular nerve is identified and preserved. The mastoid is exposed after mobilization of both the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The facial nerve is identified anterior to the mastoid process at the stylomastoid foramen. The lower cranial nerves are exposed in the neck, along with the internal jugular vein, and followed cranially to the skull base. A retromastoid craniectomy is then carried out to expose the transverse and sigmoid sinuses. The sigmoid sinus is mobilized from its bony groove caudally down to the jugular foramen. The mastoid tip is removed. To extend the exposure, the posterior part of the occipital condyle may be removed, thus opening the jugular foramen dorsolaterally. Through this approach the sigmoid sinus, the jugular bulb, and the internal jugular vein are exposed (Fig. 116-30).

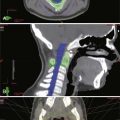

Endonasal Approaches to the Skull Base

Endonasal approaches to the skull base have been developed as an extension of microsurgical transsphenoidal approaches.59,60 They use preexisting anatomic corridors and provide access to various skull base tumors. However, a major limitation is that they permit a restricted midline exposure through a narrow surgical field. The addition of an endoscope overcomes these limitations by providing a panoramic view and the opportunity to look around the corner.60–62 The endoscope is being used as the sole device for visualization or in combination with a microscope. The expanded endoscopic endonasal technique provides access to the entire ventral skull base, from the crista galli up to the C1 vertebra.63,64 The benefits of this technique are that it avoids brain retraction and minimizes manipulation of critical structures. Furthermore, early and direct exposure of the dural attachment of the tumor with early interruption of its arterial supply is possible.

A major challenge, however, remains reconstruction of the osteodural defect. Therefore, when selecting the approach, a major issue is still the relationship of the lesion to the dura. For extradural lesions of the anterior skull base, the technique is safe and reliable (Fig. 116-31). A growing number of papers are reporting use of the technique for intradural lesions, such as olfactory meningiomas. This can hardly be justified, given the need to expose the entire intact skull base and to reconstruct it at the end of the procedure. Reported rates of cerebrospinal fluid leakage remain high despite some recent advances.65,66 A further drawback is that critical neurovascular structures, such as the anterior cerebral artery complex, lie “behind” the dissection trajectory at the tumor periphery and are visualized late. These, along with the relatively restricted working space and the two-dimensional endoscopic view, make dissection more dangerous. Alternatively, even the largest meningiomas could be removed completely with minimal risk via the simple frontolateral approach.

Boulton MR, Cusimano MD. Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(6):e10.

Brackmann DE, Green JD. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic tumor removal. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:311-329.

Chanda A, Nanda A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach: advantages and disadvantages from an anatomical perspective. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:ONS1-6.

Erkmen K, Pravdenkova S, Al-Mefty O. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: factors determining the choice of approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;15(2):E7.

Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A, et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part II. Posterior clinoids to the foramen magnum. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E4.

Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A, et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part I. Crista galli to the sella turcica. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E3.

Kawase T, Shiobara R, Toaya S. Anterior transpetrosal-transtentorial approach for sphenopetroclival meningiomas: surgical method and results in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:869-876.

Maira G, Pallini R, Anile C, et al. Surgical treatment of clival chordomas: the transsphenoidal approach revisited. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:784-792.

Nakamura M, Roser F, Jacobs C, et al. Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rate. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:626-639.

Nakamura M, Struck M, Roser F, et al. Olfactory groove meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rates after tumor removal through the frontolateral and bifrontal approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:844-852.

Rhoton ALJr. Rhoton Cranial Anatomy and Surgical Approaches. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Rhoton ALJr. The cerebellopontine angle and posterior fossa cranial nerves by the retrosigmoid approach. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:S93-129.

Rohde V, Spangenberg P, Mayfrank L, et al. Advanced neuronavigation in skull base tumors and vascular lesions. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2005;48:13-18.

Samii A, Gerganov VM, Herold C, et al. Chordomas of the skull base: surgical management and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:319-324.

Samii M, Babu RP, Tatagiba M, Sepehrnia A. Surgical treatment of jugular foramen schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:924-932.

Samii M, Draf W. Surgery of the Skull Base: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1989.

Samii M, Gerganov V, Samii A. Improved preservation of hearing and facial nerve function in vestibular schwannoma surgery via the retrosigmoid approach in a series of 200 patients. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:527-535.

Samii M, Klekamp J, Carvalho G. Surgical results for meningiomas of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:1086-1094.

Samii M, Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:248-260. discussion 260-262

Samii M, Migliori MM, Tatagiba M, et al. Surgical treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:711-718.

Samii M, Tatagiba M, Carvalho GA. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:235-241.

Samii M, Tatagiba M, Carvalho GA. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Neurosurg Sci. 1999;6:27-30.

1 Krause F. Zur Freilegung der hinteren Felsenbeinfläche und des Kleinhirns. Beitr Klin Chir. 1903;37:728-764.

2 Halstead AE. Remarks on the operative treatment of tumors of the hypophysis: report of two cases operated only by an oronasal method. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;10:494-502.

3 Panse R. Ein Gliom des Akustikus. Arch Ohrenheilk. 1904;61:251.

4 Samii M, Draf W. Surgery of the Skull Base: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1989.

5 Hassfeld S, Zoller J, Albert FK, et al. Preoperative planning and intraoperative navigation in skull base surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:220-225.

6 Gunkel AR, Vogele M, Martin A, et al. Computer-aided surgery in the petrous bone. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1793-1799.

7 Selesnick SH, Kacker A. Image-guided surgical navigation in otology and neurotology. Am J Otol. 1999;20:688-693.

8 Sure U, Alberti O, Petermeyer M, et al. Advanced image-guided skull base surgery. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:563-572.

9 Rohde V, Spangenberg P, Mayfrank L, et al. Advanced neuronavigation in skull base tumors and vascular lesions. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2005;48:13-18.

10 Thaler ER, Kotapka M, Lanza DC, et al. Endoscopically assisted anterior cranial skull base resection of sinonasal tumors. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13:303-310.

11 Tatagiba M, Matthies C, Samii M. Microendoscopy of the internal auditory canal in vestibular schwannoma surgery. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:737-740.

12 Wackym PA, King WA, Meyer GA, et al. Endoscopy in neuro-otologic surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:297-323.

13 Samii A, Gerganov VM, Herold C, et al. Chordomas of the skull base: surgical management and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:319-324.

14 Samii M, Ammirati M. Surgery of Skull Base Meningiomas. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1992.

15 Lang J. Klinische Anatomi des Kopfes. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1981.

17 Samii M, Tatagiba M, Monteiro ML. Meningiomas involving the parasellar region. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1996;65:63-65.

18 Nakamura M, Roser F, Jacobs C, et al. Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rate. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:626-639.

19 Nakamura M, Struck M, Roser F, et al. Olfactory groove meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rates after tumor removal through the frontolateral and bifrontal approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:844-852.

20 Kinjo T, Al-Mefty O, Ciric I. Diaphragma sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:1082-1092.

21 Lang J. Clinical Anatomy of the Posterior Cranial Fossa and Its Foramina. New York: Thieme; 1991.

22 Brackmann DE. Middle cranial fossa approach. In: House WF, et al, editors. Acoustic Tumors, Vol 2. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:15-41.

23 Brackmann DE, Green JD. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic tumor removal. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:311-329.

24 Day JD, Chen DA, Arriaga M. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic neuroma. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:391-395.

25 Kawase T, Shiobara R, Toaya S. Anterior transpetrosal-transtentorial approach for sphenopetroclival meningiomas: surgical method and results in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:869-876.

26 Al-Mefty O, Ayoubi S, Smith RR. The petrosal approach: indications, technique, and results. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1991;53:166-170.

27 Canalis RF, Black K, Martin N, et al. Extended retrolabyrinthine transtentorial approach to petroclival lesions. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:6-13.

28 Hirsch BE, Cass SP, Sekhar LN, et al. Translabyrinthine approach to skull base tumors with hearing preservation. Am J Otol. 1993;14:533-543.

29 Malis LI. The petrosal approach. Clin Neurosurg. 1991;37:528-540.

30 Samii M, Ammirati M. The combined supra-infratentorial presigmoid sinus avenue to the petro-clival region: surgical technique and clinical applications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;95:6-12.

31 Sekhar LN, Wright DC, Richardson R, et al. Petroclival and foramen magnum meningiomas: surgical approaches and pitfalls. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:249-259.

32 Spetzler RF, Daspit CP, Pappas CT. The combined supra and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588-599.

33 Hakuba A, Nishimura S, Inove Y. Transpetrosal-transtentorial approach and its application in the therapy of retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:405-410.

34 Sekhar LN, Schessel DA, Bucur SD, et al. Partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach to neoplastic and vascular lesions of the petroclival area. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:537-550. discussion 550-552

35 Fisch U, Kumar A. Infratemporal surgery of the skull base. In: Rand RW, editor. Microneurosurgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1985:398-420.

36 Erkmen K, Pravdenkova S, Al-Mefty O. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: factors determining the choice of approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;15(2):E7.

37 Day JD, Fukushima T, Giannotta SL. Microanatomical study of the extradural middle fossa approach to the petroclival and posterior cavernous sinus region: description of the rhomboid construct. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:1009-1016.

38 Miller CG, van Loveren HR, Keller JT, et al. Transpetrosal approach: surgical anatomy and technique. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:461-469.

39 Friedman RA, Pensak ML, Tauber M, et al. Anterior petrosectomy approach to infraclinoidal basilar artery aneurysms: the emerging role of the neuro-otologist in multidisciplinary management of basilar artery aneurysms. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:977-983.

40 Samii M, Ammirati M, Mahran A, et al. Surgery of petroclival meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:12-17.

41 Sekhar LN, Swamy NK, Jaiswal V, et al. Surgical excision of meningiomas involving the clivus: preoperative and intraoperative features as predictors of postoperative functional deterioration. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:860-868.

42 Tatagiba M, Samii M, Matthies C, et al. Management of petroclival meningiomas: a critical analysis of surgical treatment. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1996;65:92-94.

43 Samii M, Tatagiba M, Carvalho GA. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Neurosurg Sci. 1999;6:27-30.

44 Samii M, Tatagiba M. Experience with 36 surgical cases of petroclival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118:27-32.

45 Samii M, Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:248-260. discussion 260-262

46 Samii M, Gerganov V, Samii A. Improved preservation of hearing and facial nerve function in vestibular schwannoma surgery via the retrosigmoid approach in a series of 200 patients. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:527-535.

47 Ojemann RG. Retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:553-558.

48 Rhoton ALJr. The cerebellopontine angle and posterior fossa cranial nerves by the retrosigmoid approach. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:S93-129.

49 Samii M, Carvalho GA, Tatagiba M, et al. Surgical management of meningiomas originating in Meckel’s cave. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:767-774. discussion 774-775

50 Samii M, Carvalho GA, Tatagiba M, et al. Meningiomas of the tentorial notch: surgical anatomy and management. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:375-381.

51 Samii M, Klekamp J, Carvalho G. Surgical results for meningiomas of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:1086-1094. discussion 1094-1095

52 Boulton MR, Cusimano MD. Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(6):e10.

53 Samii M, Migliori MM, Tatagiba M, et al. Surgical treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:711-718.

54 Samii M, Tatagiba M, Carvalho GA. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:235-241.

55 Tatagiba M, Samii M, Matthies C, et al. The significance for postoperative hearing of preserving the labyrinth in acoustic neurinoma surgery. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:677-684.

56 Chanda A, Nanda A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach: advantages and disadvantages from an anatomical perspective. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:ONS1-6.

57 Carvalho GA, Tatagiba M, Samii M. Cystic schwannomas of the jugular foramen: clinical and surgical remarks. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:560-566.

58 Samii M, Babu RP, Tatagiba M, et al. Surgical treatment of jugular foramen schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:924-932.

59 Maira G, Pallini R, Anile C, et al. Surgical treatment of clival chordomas: the transsphenoidal approach revisited. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:784-792.

60 Jho HD, Ha HG. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: part 1—the midline anterior fossa skull base. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2004;47:1-8.

61 Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A, et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part I. Crista galli to the sella turcica. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E3.

62 Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A, et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part II. Posterior clinoids to the foramen magnum. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E4.

63 Kassam AB, Gardner P, Snyderman CH, et al. Expanded endonasal approach: fully endoscopic, completely transnasal approach to the middle third of the clivus, petrous bone, middle cranial fossa, and infratemporal fossa. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E6.

64 Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Esposito F, et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the midline skull base: the evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2008;33:151-199.

65 Snyderman CH, Kassam AB, Carrau R, et al. Endoscopic reconstruction of cranial base defects following endonasal skull base surgery. Skull Base. 2007;17:73-78.

66 de Divitiis E, Esposito F, Cappabianca P, et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: high route or low route? A series of 51 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:556-563.