1

Basic Principles of Dermatology

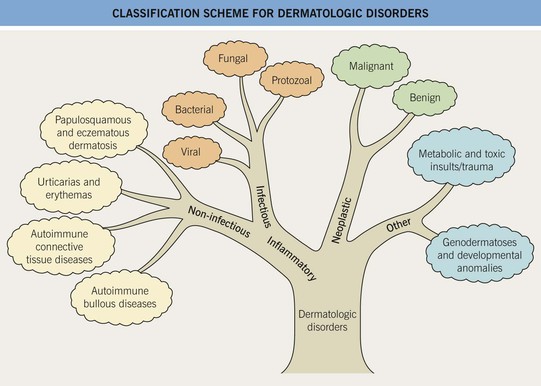

• In the approach to the patient with a dermatologic disease, it is important to think initially of broad categories (Fig. 1.1); this allows for a more complete differential diagnosis and a logical approach.

Fig. 1.1 Classification scheme for dermatologic disorders. This scheme is analogous to the structure of a tree with multiple branch points terminating in leaves.

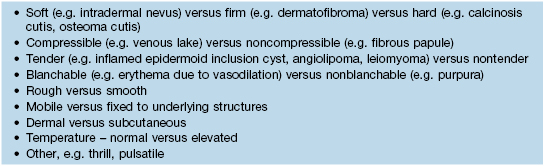

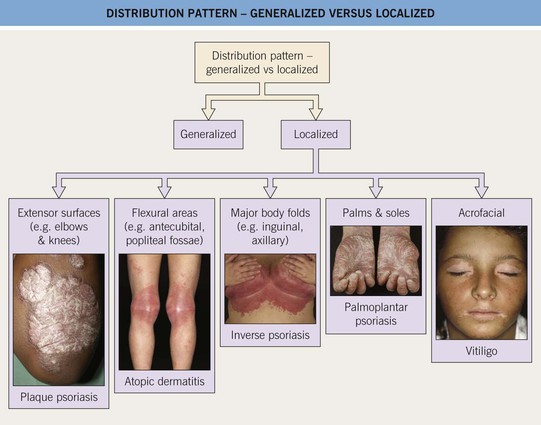

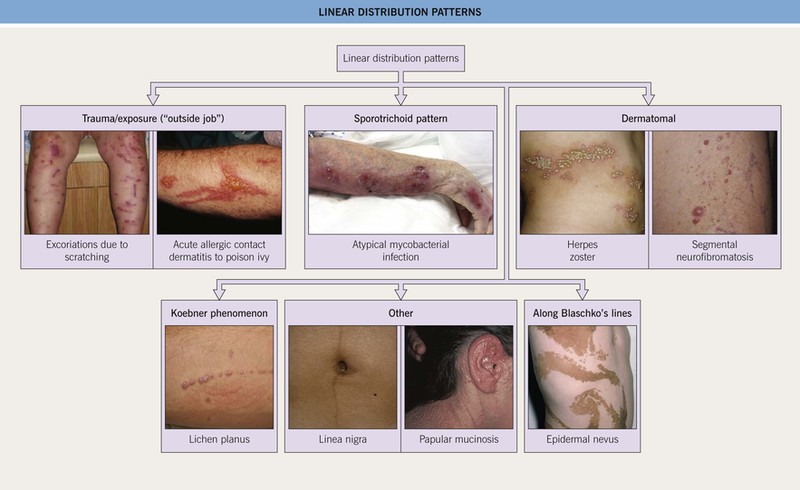

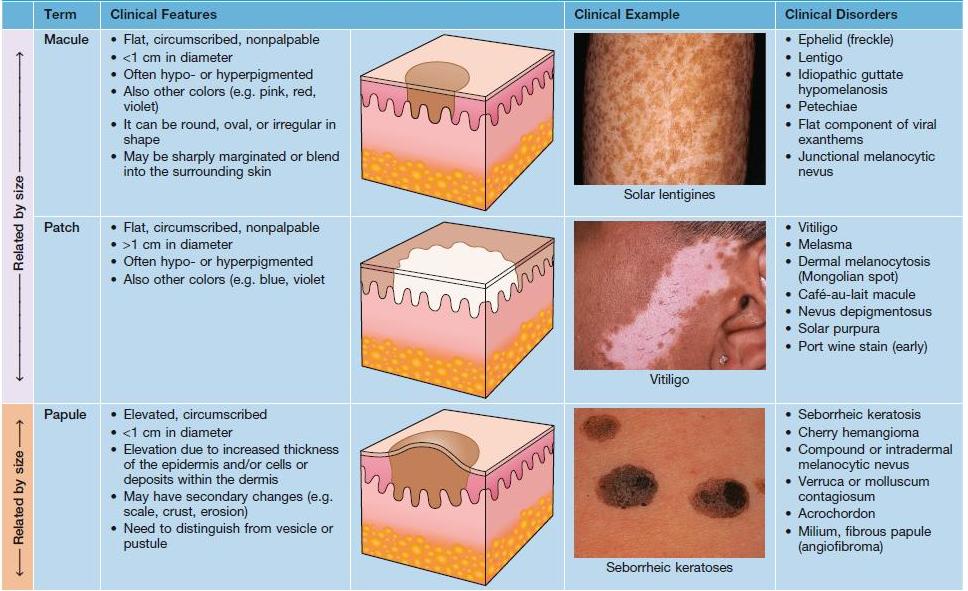

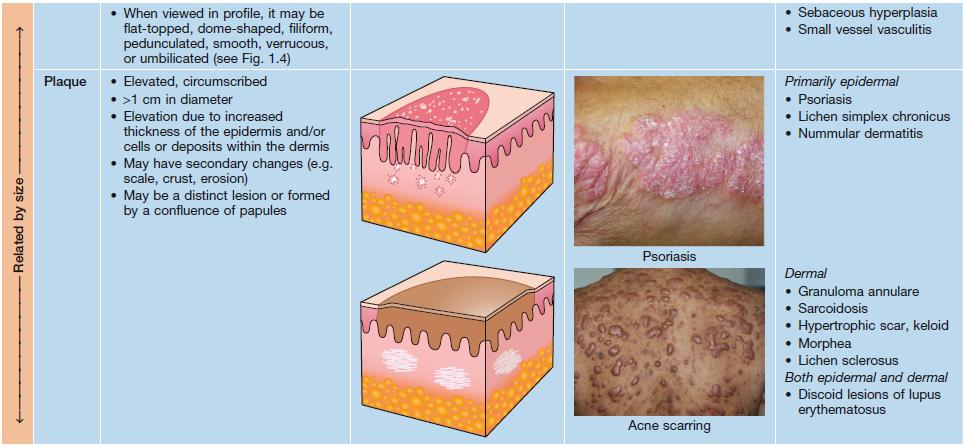

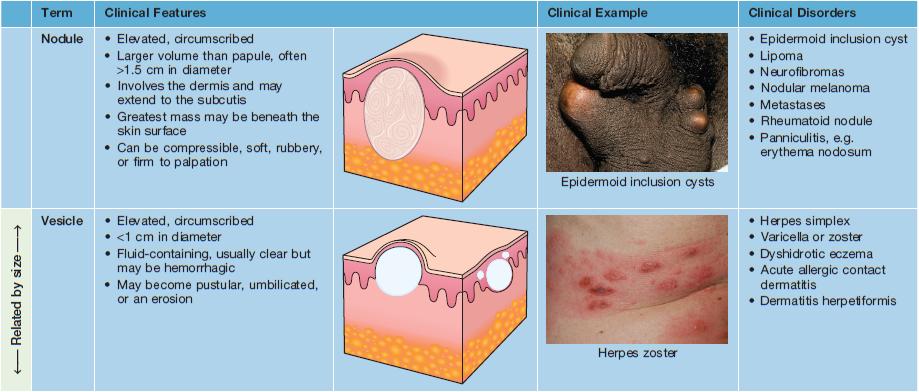

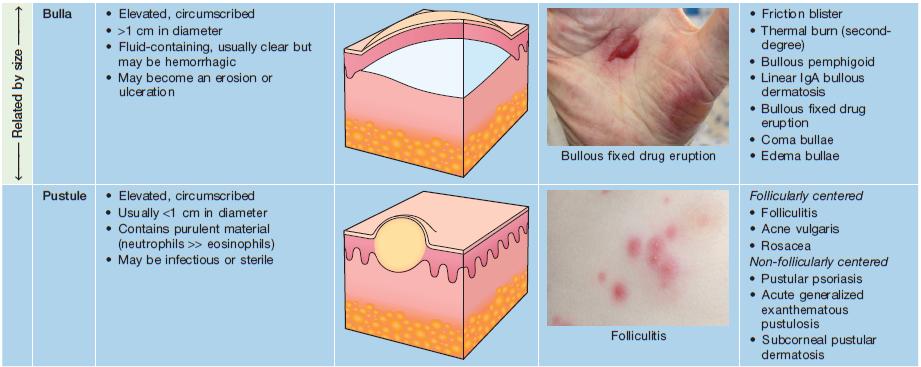

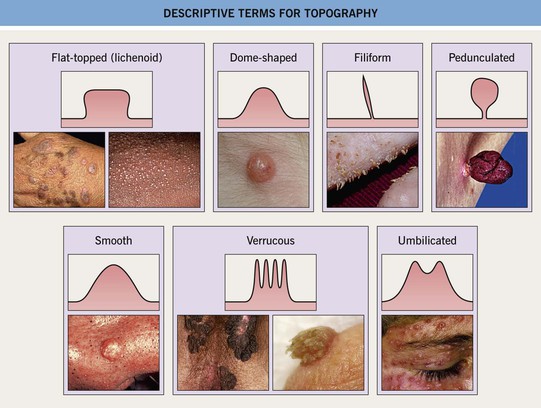

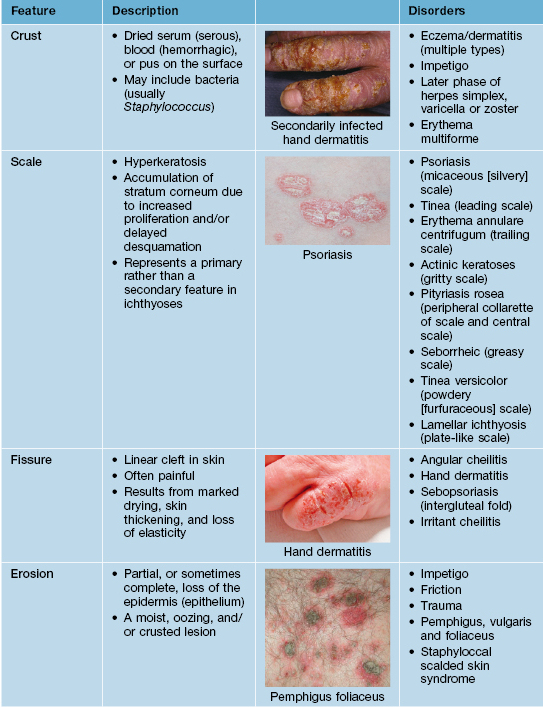

• Key elements of any clinical description include distribution pattern (Table 1.1; Figs. 1.2 and 1.3), type of primary lesion and its topography (Table 1.2; Fig. 1.4), secondary features (Table 1.3), and its consistency via palpation (Tables 1.4 and 1.5).

Fig. 1.2 Distribution pattern – generalized versus localized. In addition to these patterns, involvement of multiple mucosal sites can be seen. Photographs courtesy, Peter C. M. van de Kerkhof, MD, Thomas Bieber, MD, and Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 1.3 Linear distribution patterns. Photographs courtesy, Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD, Jean L. Bolognia, MD, Whitney High, MD, Joyce Rico, MD, and Louis Fragola, MD.

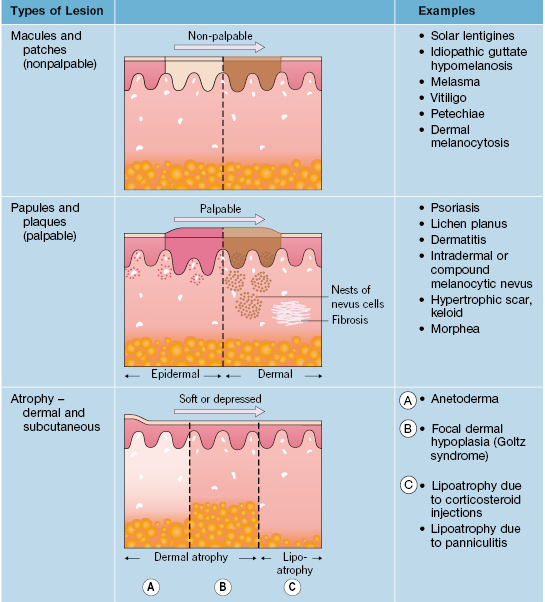

Table 1.2

Primary lesions – morphological terms.

Photographs courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD, Joyce Rico, MD, Julie V. Schaffer, MD, Kalman Watsky, MD, and Whitney High, MD.

Fig. 1.4 Descriptive terms for topography. Photographs courtesy, Jennifer Choi, MD, Hideko Kamino, MD, Reinhard Kirnbauer, MD, Petra Lenz, MD, Frank Samarin, MD, Julie V. Schaffer, MD, and Judit Stenn, MD.

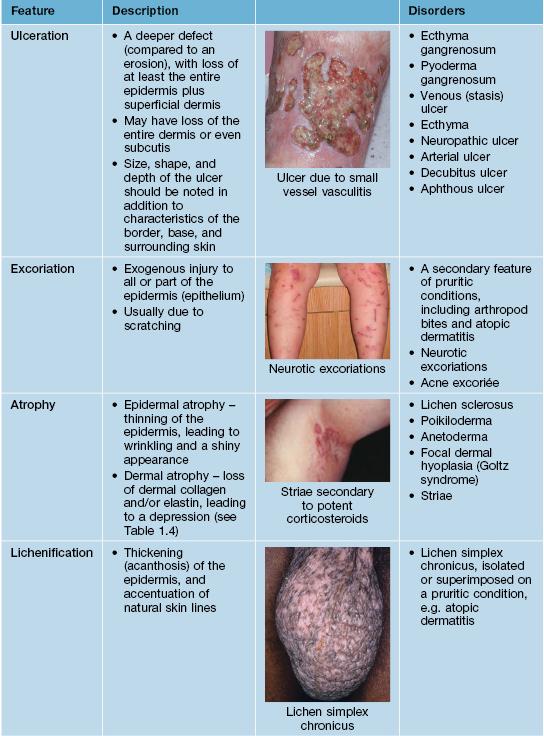

Table 1.3

Secondary features – morphological terms.

Photographs courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD, Jeffrey C. Callen, MD, Julie V. Schaffer, MD, and Whitney High, MD.

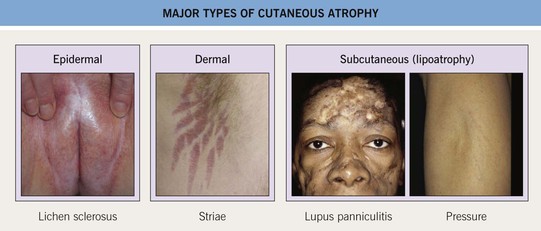

• If atrophy is present, it should be categorized as epidermal, dermal, and/or subcutaneous (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5 Major types of cutaneous atrophy. Photographs courtesy, Susan M. Cooper, MD, Fenella Wojnarowska, MD, and Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Color is also an important feature, and this can be influenced by the skin phototype (Appendix) such that an inflammatory lesion that appears pink in a patient with skin phototype I may appear red-brown to violet in a patient with skin phototype IV.

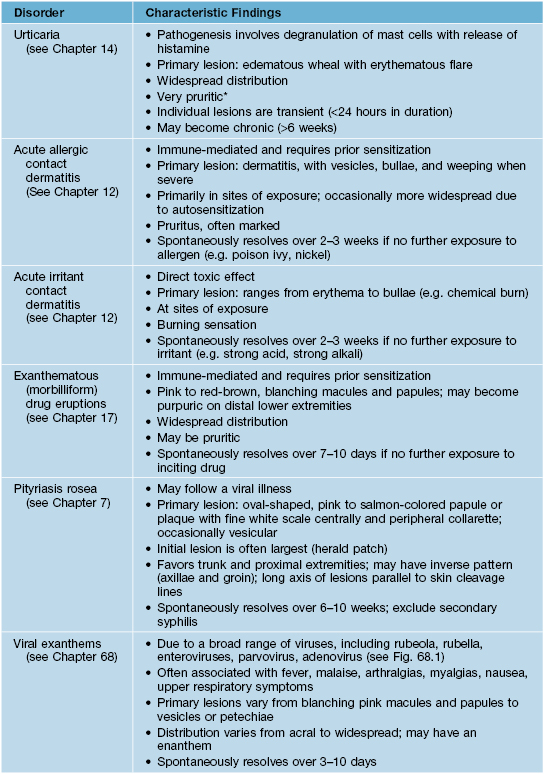

• The acuteness versus chronicity of the eruption provides additional information and with experience can often be determined without a history; Table 1.6 outlines major causes of acute eruptions in otherwise healthy individuals.

Table 1.6

Acute cutaneous eruptions in otherwise healthy individuals.

* May have have burning rather than pruritus with urticarial vasculitis, and lesions can last longer than 24 hours.

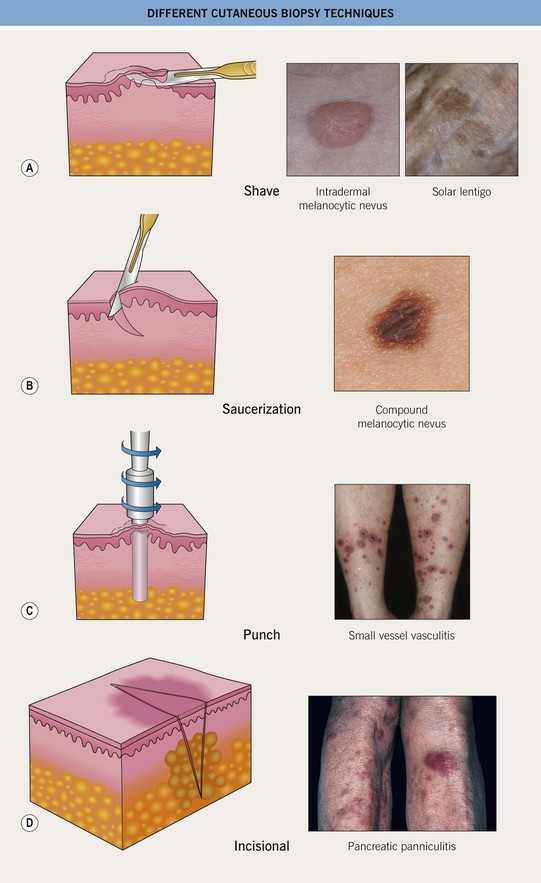

• Given the relative ease of obtaining skin biopsies, clinicopathologic correlation is a keystone of dermatologic diagnosis; however, it is important to choose the ideal lesion (e.g. in an inflammatory disorder, one that is fresh but well-developed), as well as the most appropriate type of biopsy (Fig. 1.6).

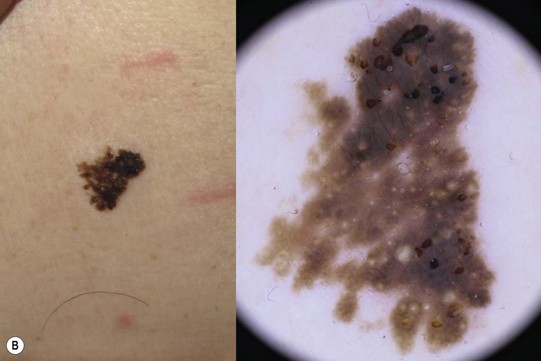

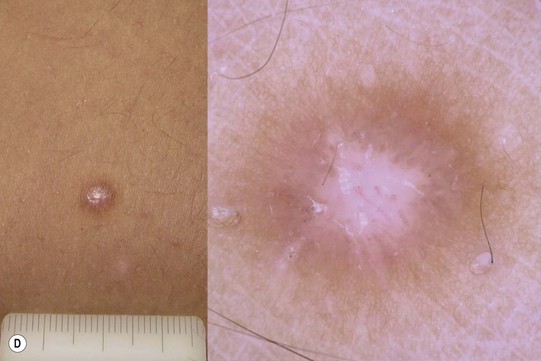

Fig. 1.6 Different cutaneous biopsy techniques. A Superficial shave biopsy can be performed to remove the elevated portion of an intradermal nevus or to distinguish a solar lentigo (pictured here) from lentigo maligna. B Deep shave biopsy (saucerization); performed to remove a compound melanocytic nevus or atypical melanocytic nevus. C Punch biopsy; performed to examine the dermis (as well as the epidermis) and the preferred technique for diagnosing cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. D Incisional biopsy; recommended for determining the specific type of panniculitis. Courtesy, Suzanne Olbricht, MD, Raymond Barnhill, MD, Kenneth Greer, MD, and Frank Samarin, MD.

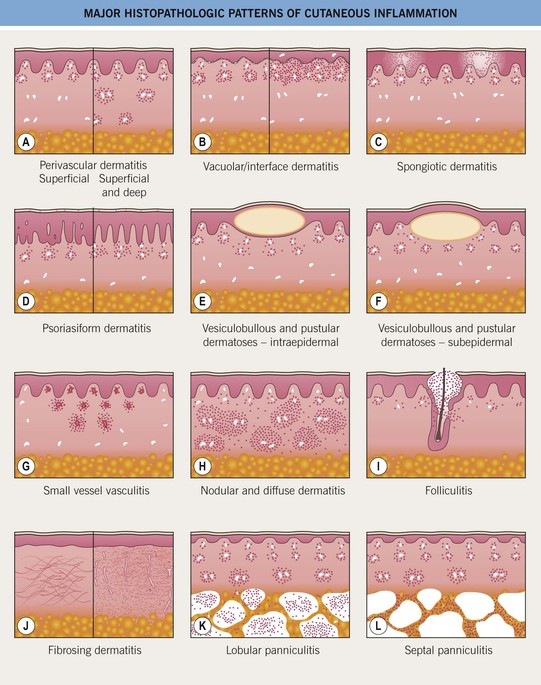

• For inflammatory disorders, there is a classification schema in which they are divided into major histopathologic patterns (Fig. 1.7); several side-by-side comparisons of clinical presentations with histologic findings illustrate the concept of clinicopathologic correlation (Figs. 1.8–1.13).

Fig. 1.7 Major histopathologic patterns of cutaneous inflammation (based on Ackerman’s classification). Basic patterns of inflammation result primarily from the distribution of the inflammatory cell infiltrate within the dermis and/or the subcutaneous fat (e.g. nodular, perivascular). It also reflects the character of the inflammatory process itself (e.g. pustular), the presence of injury to blood vessels (e.g. vasculitis), involvement of hair follicles (e.g. folliculitis), abnormal fibrous dermal and/or subcutaneous tissue, and formation of vesicles and bullae. Adapted from Ackerman AB. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Method by Pattern Analysis. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1978.

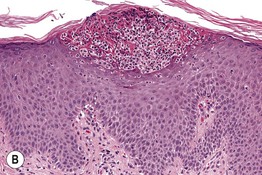

Fig. 1.8 Spongiotic dermatitis. A Acute allergic contact dermatitis to Toxicodendron radicans (poison ivy). The central black discoloration is due to the plant’s resin. B Intercellular edema (spongiosis) and vesicle formation within the epidermis. Lymphocytes are also seen in both the epidermis and dermis. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; B, Courtesy, James Patterson, MD.

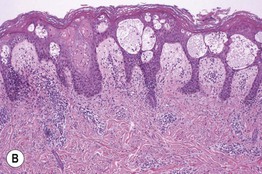

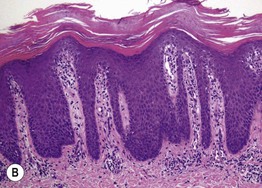

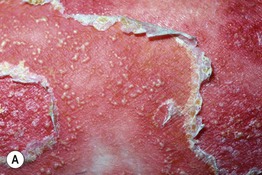

Fig. 1.9 Psoriasiform pattern. A Plaque of psoriasis vulgaris with silvery scale. B Regular epidermal hyperplasia and elongated dermal papillae with thin suprapapillary plates and confluent parakeratosis. The parakeratosis represents the histologic correlate of the visible scale. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Carlo F. Tomasini, MD.

Fig. 1.10 Intraepidermal pustular dermatosis. A Pustular psoriasis. B Collection of neutrophils beneath the stratum corneum (subcorneal pustule). Scattered neutrophils are in the upper malpighian layer. A, Courtesy, Kenneth Greer, MD; B, Courtesy, Lorenzo Cerroni, MD.

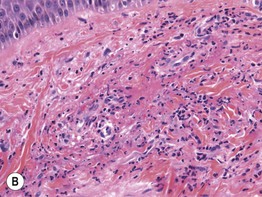

Fig. 1.11 Small vessel vasculitis. A Inflammatory palpable purpura of the leg. B Perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils with nuclear dust (leukocytoclasia). Fibrin within the vessel wall and extravasation of erythrocytes is also seen. A, Courtesy, Carlo F. Tomasini, MD; B, Courtesy, Christine Ko, MD.

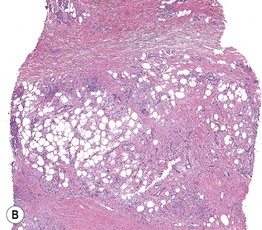

Fig. 1.12 Septal panniculitis. A Multiple red-brown nodules of erythema nodosum on the shins, admixed with healing bruise-like areas. B Predominantly septal granulomatous infiltrate with formation of characteristic Miescher’s granulomas. A, Courtesy, Kenneth Greer, MD; B, Courtesy, Christine Ko, MD.

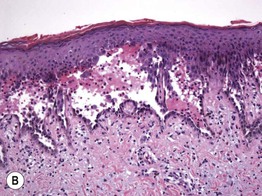

Fig. 1.13 Intraepidermal vesiculobullous dermatosis, acantholytic type. A Pemphigus vulgaris with flaccid bullae and erosions. B The keratinocytes within the lower epidermis have lost their intercellular attachments and have separated from one another, resulting in an intraepidermal blister. A, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD; B, Courtesy, Carlo F. Tomasini, MD.

• In an analogy to dermatopathology, the clinician often looks at the patient at ‘medium-power’ (i.e. 20×), but it is also important to analyze the patient at low-power (4×), thus appreciating the overall pattern, as well as high-power (100×); the latter is aided by the use of dermoscopy (Figs. 1.14 and 1.15).

Fig. 1.14 Use of dermoscopy to aid in the diagnosis of four common pigmented (nonmelanocytic) cutaneous lesions. A Pigmented basal cell carcinoma with leaf-like areas (islands of blue-gray color) at the periphery and a small erosion of reddish color at the left side of the lesion. B Seborrheic keratosis with typical milia-like cysts (white shining globules) and comedo-like openings (black targetoid globules). C Angiokeratoma with red-black lacunas clearly visible as well-demarcated roundish structures. D A dermatofibroma with characteristic central white patch and peripheral delicate pseudo-network. Dermoscopic features of melanocytic nevi and melanoma are reviewed in Chapters 92 and 93. Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, and Iris Zalaudek, MD.

Fig. 1.15 Use of dermoscopy to aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory disorders. A By dermoscopy, classic psoriasis plaques exhibit regular dotted vessels. B The dermoscopic pattern of lichen planus is definitely different from the previous one. Here, dotted vessels are seen at the border of typical whitish lines and clods, which closely resemble the Wickham striae found in lichen planus of the oral mucosa. Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, and Iris Zalaudek, MD.

For further information see Ch. 0. From Dermatology, Third Edition.