Bartonella and Afipia

1. Explain the routes of transmission for Bartonella infections, and describe the organism’s interaction with the host.

2. Discuss the clinical manifestations of Trench fever, including signs, symptoms, and individuals at risk of acquiring the disease.

3. Explain the criteria used to diagnose Bartonella henselae.

4. Describe the two methods for culturing Bartonella, including growth rates, media, incubation temperature, and other relevant conditions.

5. Explain why the sensitivity and specificity has been questioned with indirect fluorescent antibody and enzyme-linked immunoassay testing.

6. Describe the strategies to prevent exposure and infection by these organisms in immunocompromised individuals.

Bartonella

General Characteristics

Bartonella spp. were previously grouped with members of the family Rickettsiales. However, because of extensive differences, the family Bartonellaceae was removed from this order. As a result of phylogenetic studies using molecular biologic techniques, the genus Bartonella currently includes 22 species and subspecies, most of which were reclassified from the genus Rochalimeae and from the genus Grahamella. Only five species are currently recognized as major causes of disease in humans (Table 33-1), but other members of the genus have been found in animal reservoirs such as rodents, ruminants, and moles. Bartonella spp. are most closely related to Brucella abortus and Agrobacterium tumefaciens and are short, gram-negative, rod-shaped, facultative intracellular, fastidious organisms that are oxidase negative and grow best on blood-enriched media or cell co-culture systems.

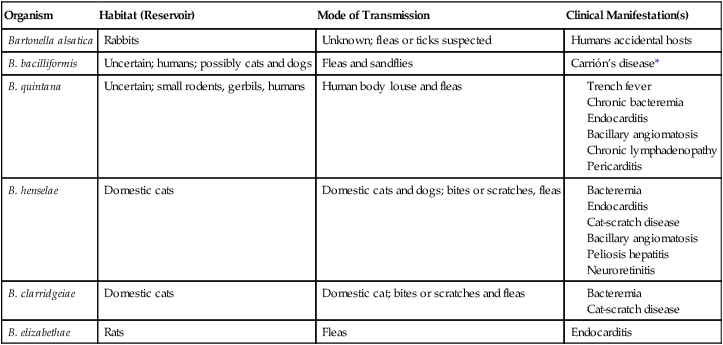

TABLE 33-1

Organisms Belonging to the Genus Bartonella and Recognized to Cause Disease in Humans*

| Organism | Habitat (Reservoir) | Mode of Transmission | Clinical Manifestation(s) |

| Bartonella alsatica | Rabbits | Unknown; fleas or ticks suspected | Humans accidental hosts |

| B. bacilliformis | Uncertain; humans; possibly cats and dogs | Fleas and sandflies | Carrión’s disease* |

| B. quintana | Uncertain; small rodents, gerbils, humans | Human body louse and fleas | |

| B. henselae | Domestic cats | Domestic cats and dogs; bites or scratches, fleas | |

| B. clarridgeiae | Domestic cats | Domestic cat; bites or scratches and fleas | |

| B. elizabethae | Rats | Fleas | Endocarditis |

Note: Other Bartonella species have caused incidental infections in humans, but only one or a few cases have been documented.

*Disease confined to a small endemic area in South America; characterized by a septicemic phase with anemia, malaise, fever, and enlarged lymph nodes in the liver and spleen, followed by a cutaneous phase with bright red cutaneous nodules, usually self-limited.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Organisms belonging to the genus Bartonella cause numerous infections in humans; most of these infections are thought to be zoonoses. Interest in these organisms has increased because of their recognition as causes of an expanding array of clinical syndromes in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. For example, Bartonella species have been recognized with increasing frequency since the early 2000s as a cause of culture-negative endocarditis. Humans acquire infection either naturally (infections caused by Bartonella quintana or Bartonella bacilliformis) or incidentally (other Bartonella species) via arthropod-borne transmission. Nevertheless, questions remain regarding the epidemiology of these infections; some epidemiologic information is summarized in Table 33-1.

Spectrum of Disease

The diseases caused by Bartonella species are listed in Table 33-1. Because B. quintana and B. henselae are more common causes of infections in humans, these agents are addressed in greater depth.

B. henselae is associated with bacteremia, endocarditis, and bacillary angiomatosis. Of note, recent observations indicate that B. henselae infections appear to be subclinical and are markedly underreported, as problems with current diagnostic approaches are recognized (see Laboratory Diagnosis). In addition, B. henselae causes CSD and peliosis hepatitis. About 24,000 cases of CSD occur annually in the United States; about 80% of these occur in children. The infection begins as a papule or pustule at the primary inoculation site; regional tender lymphadenopathy develops in 1 to 7 weeks. The spectrum of disease ranges from chronic, self-limited adenopathy to a severe systemic illness affecting multiple body organs. Although complications such as a suppurative (draining) lymph node or encephalitis are reported, fatalities are rare. Diagnosis of CSD requires three of the four following criteria:

• History of animal contact plus site of primary inoculation (e.g., a scratch)

• Negative laboratory studies for other causes of lymphadenopathy

• Characteristic histopathology of the lesion

• A positive skin test using antigen prepared from heat-treated pus collected from another patient’s lesion

Bartonella clarridgeiae is a newly described species capable of causing CSD and bacteremia.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection, Transport, and Processing

Clinical specimens submitted to the laboratory for direct examination and culture include blood, which has been collected in a lysis-centrifugation blood culture tube (Isolator; Wampole Laboratories, Cranbury, New Jersey), as well as aspirates and tissue specimens (e.g., lymph node, spleen, or cutaneous biopsies). There are no special requirements for specimen collection, transport, or processing that enhances organism recovery. Refer to Table 5-1 for general information on specimen collection, transport, and processing.

Direct Detection Methods

Detection of Bartonella spp. during the histopathologic examination of tissue biopsies is enhanced with staining using the Warthin-Starry silver stain orimmunofluorescence and immunohistochemical techniques. Because of the fastidious nature of the organisms and slow growth, molecular methods to identify Bartonella spp. directly in clinical specimens allows earlier detection. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic transcribed spacer region has been proposed as a reliable method for the detection of Bartonella DNA in clinical samples. However, a recent study revealed some potential limitations based on insufficient primer specificity. As the number of species included in the genus expand, PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (see Chapter 8) as well as sequencing may require targeting several genes and subsequent sequencing for accurate species identification.

Approach to Identification

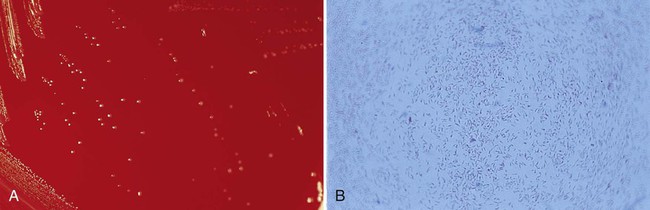

Bartonella spp. should be suspected when colonies of small, gram-negative bacilli are recovered after prolonged incubation (Figure 33-1). Organisms are all oxidase, urease, nitrate reductase, and catalase negative. Various methods may be used for confirmation and identification of Bartonella spp. Species identification is possible by adding 100 μg/mL of hemin to the test medium, as well as biochemical profiling using the MicroScan rapid or Rapid ANAII system (Innovative Diagnostic Systems, Norcross, Georgia) anaerobe panels, polyvalent antisera, or a variety of molecular methods.

1. Humans acquire Bartonella infection by:

2. Most Bartonella infections are thought to be:

3. Bartonella is characterized by all of the following, except:

4. Bartonella quintana has been known to cause:

5. Bartonella species can be detected by which of the following?

6. IFA testing for Bartonella has been known to cross-react with:

7. Which of the following aid in Bartonella prevention for the immunocompromised patient?