61

Bacterial Diseases

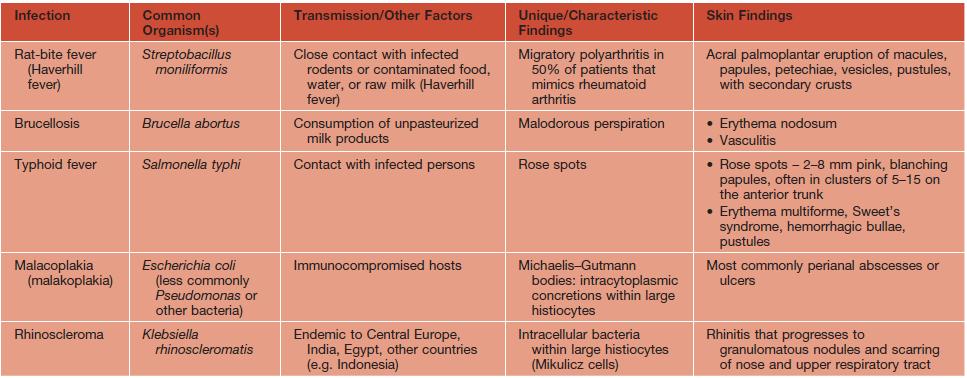

Skin infection with bacteria may be a primary problem (e.g. impetigo) or a complication of another skin disease (e.g. atopic dermatitis). Nomenclature of these diseases often reflects the site and the depth of infection – that is, from the stratum corneum to the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 61.1) – as well as the suspected causative organism.

Fig. 61.1 Categorization of bacterial infections by depth and extent of skin involvement. More common, localized infections are depicted first; these infections are often secondary to Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Adapted from ‘Common bacterial infections of the skin,’ American Academy of Dermatology.

Gram-Positive Cocci

Staphylococcal and Streptococcal Skin Infections

Streptococcal infections may be complicated by acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis; this occurs in <1% of patients in high-income countries, but it remains a significant problem in low-income countries.

Impetigo

• Major organisms are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci [GAS]).

• A very common, highly contagious bacterial infection, most commonly seen on the face or extremities of children; usually the skin is eroded with overlying ‘honey-colored’ crusts, but there is a bullous variant (Fig. 61.2).

Fig. 61.2 Staphylococcal impetigo. A Honey-colored crusts on the chin and cheeks of a child with impetigo. B Superficial bullae and dry erosion on the nose due to bullous impetigo. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Interestingly, bullae formation due to S. aureus can be explained by local release of an exfoliative toxin that binds to desmoglein 1 and leads to dissolution (i.e. acantholysis) of the upper epidermis (see Chapter 23).

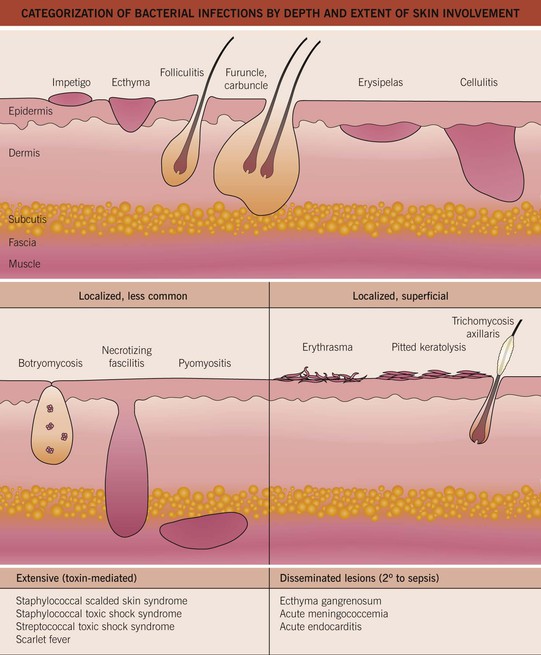

• Rx: local wound care (including soap), removal of crusts by soaking; for mild cases, topical mupirocin or retapamulin; for moderate to severe infections, oral antibiotics, the choice of which is dependent on prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the local community (Table 61.1).

Table 61.1

Empiric treatment of cutaneous staphylococcal and streptococcal infections in adults.

Treatment duration is usually 7–10 days, depending on the severity and clinical response. Initial choice of antibiotic is dependent on known resistance patterns in a given community. The contents of pustules or exudate (e.g. underlying a crust) should be sent for culture and sensitivities prior to beginning therapy. Quinolones and macrolides are not optimal for treatment of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) because resistance is common and may develop rapidly.

* Does not provide coverage of group A streptococci; if coverage of the latter is desired, a β-lactam is also prescribed.

MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Ecthyma

• Most commonly secondary to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Ulceration with hemorrhagic crust that extends into the superficial dermis, i.e. is deeper than impetigo (Fig. 61.3); can heal with scarring.

Bacterial Folliculitis

• Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause, followed by gram-negative bacteria; the latter can occur in patients with acne vulgaris on long-term antibiotic therapy; see Chapter 31 for Pseudomonas folliculitis.

• Usually superficial, but occasionally deep, infection centered on hair follicles (see Fig. 61.1).

– Superficial – 1- to 4-mm pustules on an erythematous base (see Fig. 31.2); centrally, a hair shaft may be noted.

• DDx: culture-negative (normal flora) folliculitis, acne vulgaris, folliculitis due to fungi (e.g. Pityrosporum) or viruses (e.g. herpes simplex virus), rosacea, and pseudofolliculitis barbae (see Chapter 31).

• Rx: for superficial form – antibacterial washes (e.g. benzoyl peroxide, chlorhexidine) or topical gels (e.g. combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide); widespread staphylococcal folliculitis – oral antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

Abscesses, Furuncles, and Carbuncles

• By definition, a furuncle involves a hair follicle; involvement of multiple, adjacent follicles is termed a carbuncle (see Fig. 61.1).

• Clinically, furuncles appear as firm, tender, red nodules; carbuncles begin similarly but become larger in size and can develop multiple draining sinus tracts.

• Common locations are the face, neck, axillae, buttocks, perineum, and thighs.

• DDx: ruptured epidermoid inclusion cyst, hidradenitis suppurativa, and cystic acne.

• Rx: fluctuant lesions should be incised and drained; systemic antibiotics are generally reserved for: (1) furuncles around the nose, in the external auditory canal, or in other locations where drainage is difficult; (2) severe or extensive disease (e.g. multiple sites); (3) lesions with surrounding cellulitis/phlebitis or associated with signs or symptoms of systemic illness; (4) lesions not responding to local care; and (5) patients with concerning comorbidities or immunosuppression (see Table 61.1 for Rx options).

Erysipelas

• Most commonly due to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Presents as a well-defined area of hot, indurated, bright erythema that is painful and tender (Fig. 61.4); occasionally, there may be superimposed pustules, vesicles, bullae, or areas of hemorrhagic necrosis.

Fig. 61.4 Cutaneous manifestations of streptococcal infections. Prominent desquamation of the feet (A) following scarlet fever. Sharply demarcated erythema of the face, most obvious on the forehead (B), and of the buttocks (C) in two patients with erysipelas. Bright red erythema extending from the anal verge in a young boy with streptococcal perianal disease (D). A, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD; B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, Courtesy, Mary Stone, MD; D, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Favors the young, debilitated, elderly, and limbs with edema or lymphedema.

Streptococcal Intertrigo/Perianal Disease

Cellulitis

• Infection of the deep dermis and sometimes the subcutaneous fat (see Fig. 61.1).

• Skin rubor (redness), calor (warmth), dolor (pain), and tumor (swelling) are present; more ill-defined borders than erysipelas and may have skip areas; can become bullous or necrotic (Figs. 61.5 and 75.8).

Fig. 61.5 Bullous cellulitis. Extensive soft tissue infection of the lower extremity due to group A streptococcal infection.

• Systemic symptoms include fever, chills, and malaise; CBC usually shows leukocytosis and bandemia.

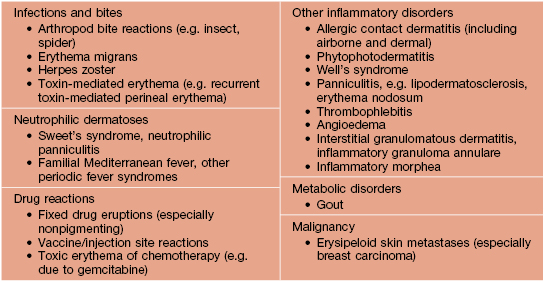

• DDx: on the lower extremity, lipodermatosclerosis and stasis dermatitis (see Fig. 11.5); elsewhere, erysipelas and the early stage of necrotizing fasciitis, as well as causes of pseudocellulitis (Table 61.2).

Blistering Distal Dactylitis

Botryomycosis

• Most commonly caused by S. aureus, followed by Pseudomonas spp.

• Grains, representing macroscopic colonies of bacteria, are seen in biopsy specimens as well as the pustular discharge; grains are also seen in eumycotic and actinomycotic mycetoma (see Chapter 64) and actinomycosis (see below).

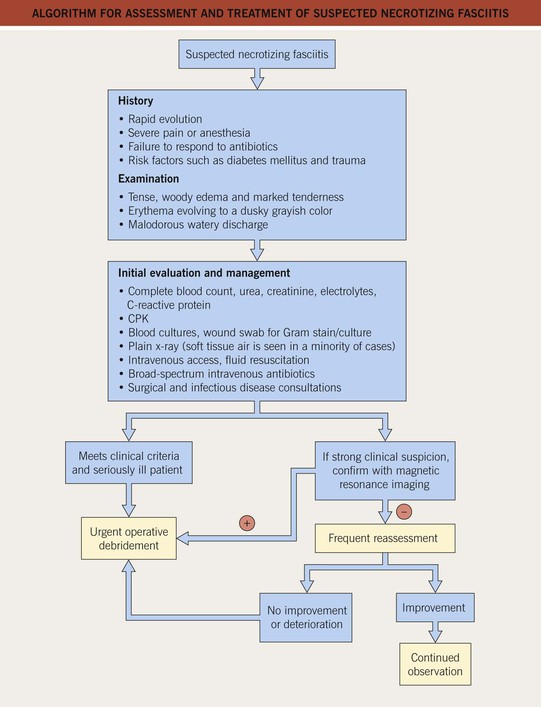

Necrotizing Fasciitis

• Usually represents polymicrobial infection with both anaerobes and aerobes; ~10% secondary to GAS.

• Initially may resemble cellulitis, but associated pain is often out of proportion to the clinical findings; additional clues include tense edema and a violaceous or gray color reflecting impending necrosis (Figs. 61.6 and 75.9).

Fig. 61.6 Necrotizing fasciitis. Necrosis of the subcutaneous fat and fascia of the inner aspect of the upper arm in an elderly patient with diabetes mellitus. Note the watery discharge. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Patients may have fever, chills, malaise, and leukocytosis.

• Rx: surgical debridement is the mainstay of therapy; broad-spectrum IV antibiotics.

Pyomyositis

• Primary bacterial infection of skeletal muscle, most commonly with S. aureus (see Fig. 61.1); associated with immunosuppression, including HIV infection.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS)

• Tender erythema on the face and in intertriginous zones that generalizes to the remainder of the body over 1 or 2 days; due to the split in the upper epidermis, the skin becomes ‘wrinkled’ and then sloughs over 3–5 days, leading to denuded areas; on the face, radial fissures with scale-crust develop around the mouth and eyes (see Fig. 3.11).

• Rx: hospitalization and IV anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

Toxic Shock Syndrome (Other Than Streptococcal) (TSS)

• Secondary to Staphylococcus aureus, which produces an exotoxin, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1.

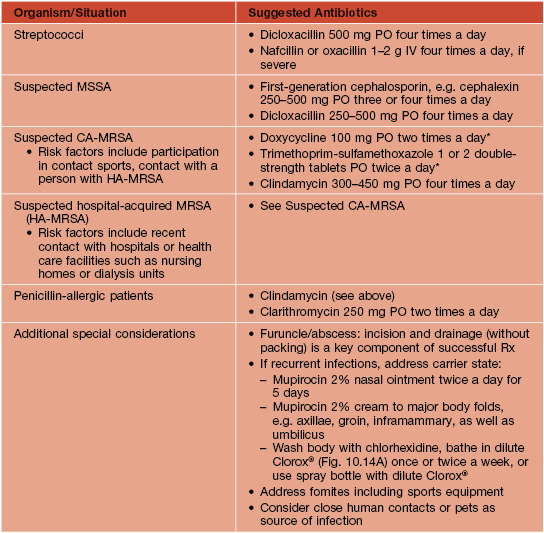

• Case definition of staphylococcal TSS is outlined in Table 61.3.

Table 61.3

Case definitions for the toxic shock syndromes.

For details on the current case definitions, see wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss and enter condition name as ‘toxic shock syndrome’ or ‘streptococcal toxic shock syndrome’.

* Defined as a definite case.

† Defined as a probable case, excluding any other possible etiology.

• Mucous membrane findings: erythema, strawberry tongue, hyperemia of the conjunctivae (Fig. 61.8).

streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (Streptococcal TSS)

Scarlet Fever

• Secondary to GAS, which produce erythrogenic toxins types A, B, and C.

• Seen in children (ages 1–10 years), usually following streptococcal tonsillitis or pharyngitis.

• Pastia lines (linear petechial streaks) are seen in major body folds, e.g. axillary, inguinal, antecubital.

• Desquamation of distal digits occurs after 7–10 days.

• Postinfectious sequelae include acute glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever.

Bacteremia/Septicemia

Gram-Positive Bacilli

Clostridial Skin Infections

Corynebacterium (And Kytococcus) Skin Infections

Erythrasma

• Superficial, localized infection due to Corynebacterium minutissimum.

• Three major clinical variants.

– Intertriginous – thin red-brown plaques in the axillae and groin/upper inner thigh that may be misdiagnosed as tinea cruris (see Table 60.5; Fig. 61.9).

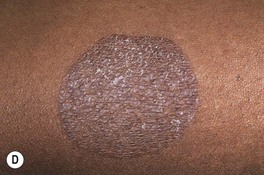

Fig. 61.9 Erythrasma. A Pink to brown scaly patches on the upper inner thighs. B Coral-red fluorescence upon illumination with a Wood’s lamp. C Hyperpigmented plaques in the inguinal and periumbilical areas (intertriginous zones). D Well-demarcated, scaly, hyperpigmented plaque of disciform erythrasma. A, B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, MD.

– ‘Disciform’ – often on the trunk and diabetes mellitus is a risk factor (Fig. 61.7D).

• Bright, coral-red fluorescence with Wood’s lamp examination (see Figs. 61.9B and 13.2).

Pit ted Keratolysis

• Secondary to Kytococcus sedentarius (Micrococcus sedentarius) and Corynebacterium spp.

• Hyperhidrosis, prolonged occlusion, and increased surface pH are contributing factors; the latter plus bacterial infection lead to 1- to 3-mm crater-like depressions in the stratum corneum that may coalesce, with involvement of soles >> palms (Fig. 61.10).

Fig. 61.10 Pitted keratolysis of the plantar surface of the foot. Multiple small craters with decreased stratum corneum that favor pressure points on the plantar surface. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

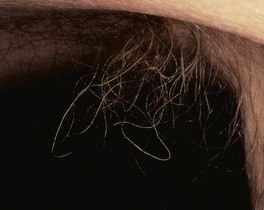

Trichomycosis Axillaris

• Common disorder that may be clinically subtle; often accompanied by malodor.

• Hair shafts are ensheathed with adherent yellow > red or black concretions composed of organisms (Fig. 61.11); most common in the axillae and a cause of chromhidrosis (see Chapter 32).

Fig. 61.11 Trichomycosis axillaris. Cylindrical sheaths and beading of the axillary hairs. A yellow color is seen most commonly.

• DDx: other causes of nodules on hair shafts (see Fig. 64.3).

Other Gram-Positive Skin Infections

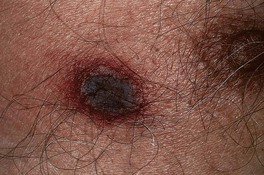

Anthrax

• Bacillus anthracis causes inhalational, gastrointestinal, and cutaneous disease.

• Emerged as an agent of biological terrorism.

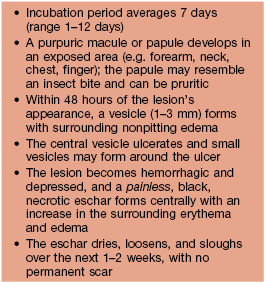

• Clinical characteristics of cutaneous disease are outlined in Table 61.4.

Table 61.4

Cutaneous anthrax – clinical characteristics.

Adapted from Carucci JA, McGovern TW, Norton SA, et al. Cutaneous anthrax management algorithm. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;47:766–769.

• Rx for cutaneous disease: fluoroquinolone (e.g. ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO twice daily) for 60 days.

Erysipeloid

• Due to Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae.

– Localized cellulitis – infection due to traumatic inoculation; seen in individuals who prepare fish and meat; the hand is a frequent site of involvement and the color is characteristically red-violet (Fig. 61.12).

• Rx for localized form: penicillin 500 mg PO four times a day for 7–10 days.

Gram-Negative Cocci

Acute Meningococcemia

• Systemic infection due to Neisseria meningitides.

• In most individuals, infection results in an asymptomatic carrier state.

• In acute meningococcemia, one-third to one-half of patients have skin lesions due to septic emboli, initially subtle petechiae that evolve into irregularly shaped purpura with a central gunmetal gray color that reflects necrosis (Fig. 61.13); gram-negative cocci may be seen on Gram staining of lesional tissue.

Fig. 61.13 Acute meningococcemia. Purpura with irregular outline and central gunmetal gray color. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• The septic lesions are to be distinguished from those due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Table 18.1).

• Rx: IV penicillin or ceftriaxone; vaccination is important for prevention.

Chronic Meningococcemia

Gonorrhea & Disseminated Gonococcal Infection

See Chapter 69.

Gram-Negative Bacilli

Pseudomonal Infections

Green nail syndrome is discussed in Chapter 58.

Gram-Negative Toe-Web Infection

• Risk factors are pre-existing tinea pedis and occlusion (e.g. tight-fitting shoes).

• Symptoms of burning and pain; signs include a malodorous exudate with a blue-green tinge, a grape-juice odor, and a moth-eaten appearance of skin due to maceration and erosions (Fig. 61.14).

Otitis Externa (‘Swimmer’s Ear’)

Pseudomonal Folliculitis (Hot Tub Folliculitis)

See Table 31.2.

Pseudomonas Hot-Foot Syndrome

• Painful and tender, red-purple, 1- or 2-cm nodules appear on the weight-bearing aspects of the feet (Fig. 61.15).

Fig. 61.15 Pseudomonas hot-foot syndrome. Tender erythematous nodules on the heel. Courtesy, Justin J. Green, MD.

• Self-limiting and DDx is primarily idiopathic palmoplantar hidradenitis (Chapter 32).

Ecthyma Gangrenosum

• A sign of bacteremia or septicemia.

• A red-purple macule or patch that develops central necrosis; sometimes the necrosis is preceded by a hemorrhagic bulla; the number can vary from one to a dozen or more (Fig. 61.16).

Fig. 61.16 Ecthyma gangrenosum. Embolic lesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on the chest. Note the necrotic center and inflammatory border.

• The most common location for ecthyma gangrenosum due to Pseudomonas is the groin.

• To establish the diagnosis, culture of tissue, obtained via sterile biopsy technique (see Fig. 2.10), is performed in combination with histopathology.

Treatment of Pseudomonal Infections

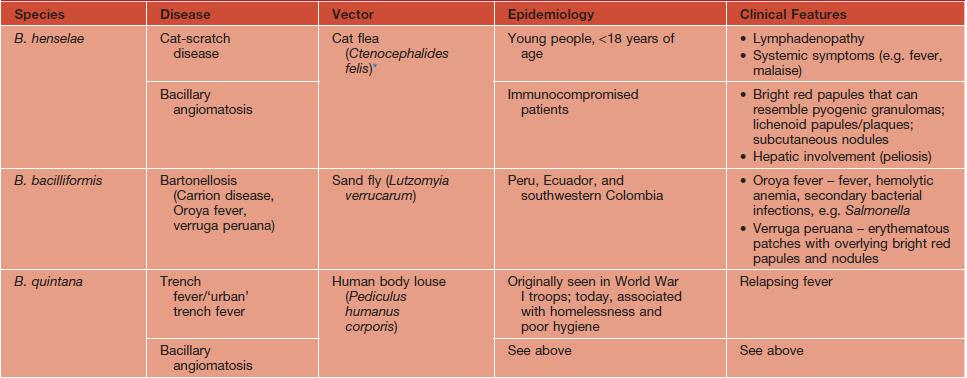

Diseases Caused by Bartonella Species

See Table 61.5.

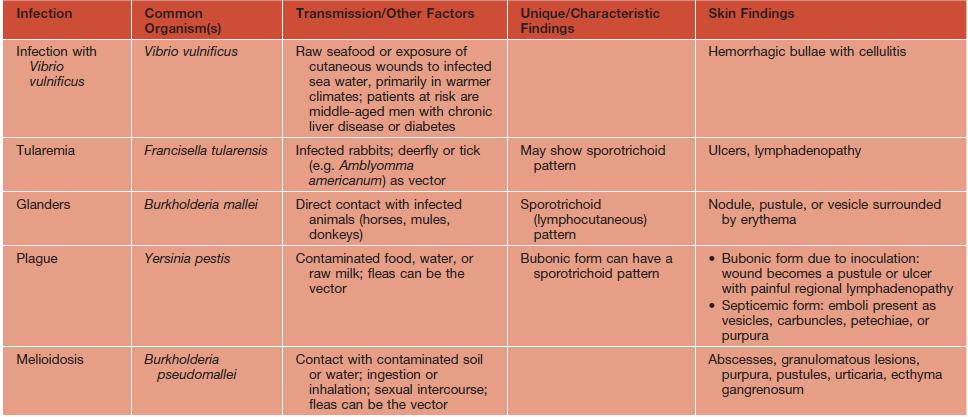

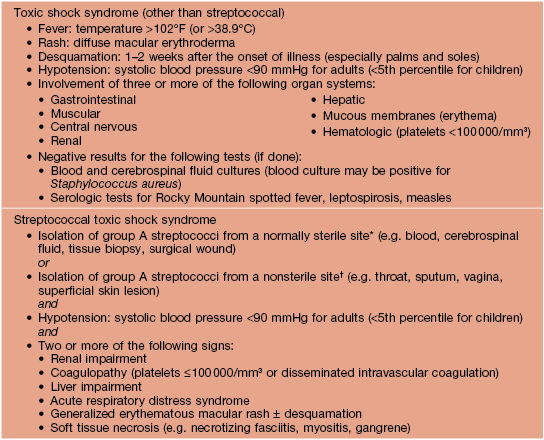

Other Gram-Negative Skin Infections with Fever and Skin Findings

See Table 61.6.

Spirochetes

Lyme Disease

See Chapter 15.

Syphilis

See Chapter 69.

Other Treponemal Diseases

• Like syphilis, other treponemal diseases may have primary, secondary, and tertiary stages.

– Due to Treponema pallidum endemicum.

– Seen most commonly in Africa, the Arabian peninsula, and Southeast Asia.

– Children younger than the age of 15 years are most often affected.

– Primary lesion often missed.

– Secondary stage: macerated patches on lips, tongue, and pharynx; angular stomatitis; condyloma lata; generalized lymphadenopathy.

– Tertiary stage: gummas that can lead to destruction of the palate and nasal septum.

• Pinta.

– Seen primarily in Central and South America.

– Tertiary stage: symmetric, depigmented, vitiligo-like lesions that are atrophic or keratotic.

• Yaws.

– Due to T. pallidum pertenue.

– Seen in warm, humid, tropical climates.

– Children younger than the age of 15 years are most often affected.

– Secondary: smaller lesions adjacent to orifices or adjacent to site of initial primary lesion (Fig. 61.17).

Filamentous Bacteria

Actinomycosis

• Most commonly due to Actinomyces israelii.

• Three major sites of involvement – cervical, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal.

• Skin involvement is most common with the cervical variant and is sometimes referred to as ‘lumpy jaw’ due to irregular subcutaneous nodules; the latter can drain and the exudate contains grains (Fig. 61.18).

Actinomycotic Mycetoma

• Most commonly due to Nocardia as well as Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri, and Streptomyces somaliensis; organisms are found in soil and on plant material (Table 61.7).

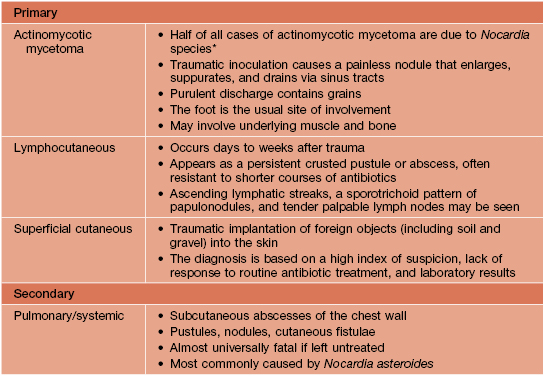

Table 61.7

Four major clinical forms of cutaneous nocardiosis.

Rx: Sulfonamides are the drugs of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis, with minocycline being an alternative for sulfonamide-allergic patients. Duration of treatment is at least 6-12 weeks for localized disease in immunocompetent hosts. Surgical excision may be required for deep abscesses.

* In Mexico and Central and South America, N. brasiliensis is the etiologic agent of 90% of actinomycotic mycetomas, whereas in the United States, most mycetomas are caused by true fungi.