48 Bacterial Diseases

Common Syndromes

Bacterial Meningitis

Pathophysiology

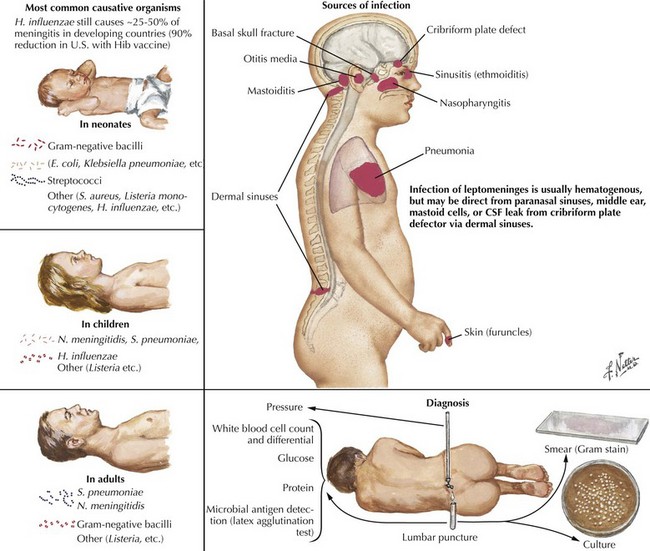

Bacterial meningitis is defined as a microbial infection primarily involving the leptomeninges (Fig. 48-1). Typically, bacteria seed the leptomeninges via the bloodstream or from a contiguous site of infection, such as sinusitis, otitis media, or mastoiditis. Rarely a defect in the normal anatomic barriers, as with a perforating cranial or spinal injury or congenital dural defect, leads to a predisposition to recurrent bacterial meningitis.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

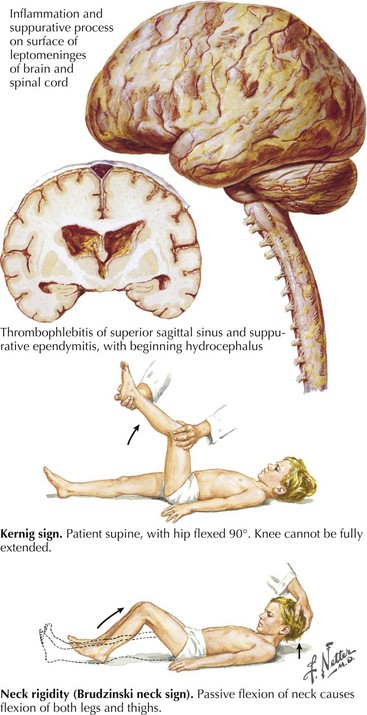

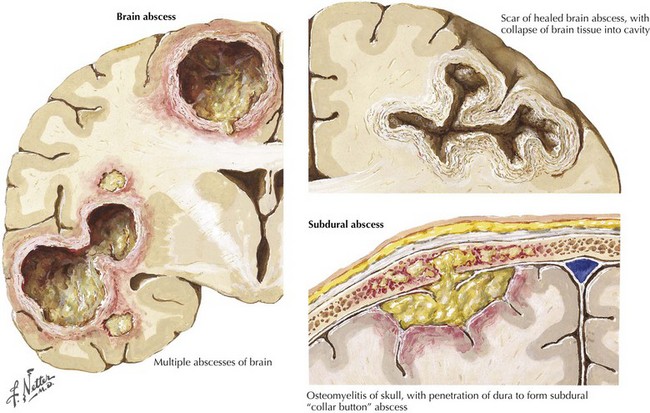

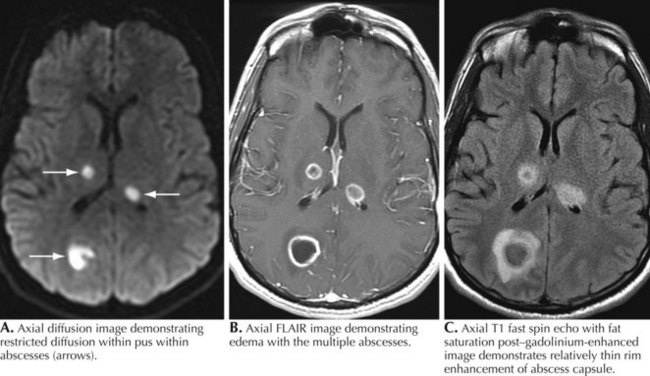

The examining physician needs to carefully search for signs of nuchal rigidity in any febrile patient who presents with a headache or any changes in level of alertness. Two clinical maneuvers are very important for identifying the presence of inflamed meningeal coverings involving the lumbosacral nerve roots: the Kernig and Brudzinski signs (Fig. 48-2). The Kernig sign is elicited by flexing the patient’s hip to a 90-degree angle and then attempting to passively straighten the leg at the knee; pain and tightness in the hamstring muscles prevent completion of this maneuver. This sign should be present bilaterally to support a diagnosis of meningitis. The Brudzinski sign is positive if the patient’s hips and knees flex automatically when the examiner flexes the patient’s neck while the patient is supine. Because host responsiveness to the infection varies, these signs of meningeal irritation are not invariably present, especially in debilitated and elderly patients and infants. When the clinical picture is typical of meningitis, it is also very important to exclude the concomitant presence of a focal parameningeal source such as a brain abscess. Further history, careful neurologic examination, and various imaging studies are essential (Figs. 48-3 and 48-4). Frequently there may be concomitant dermatologic findings present. A maculopapular or petechial/purpuric rash usually indicates infection with N. meningitidis although an echovirus may mimic such. However, in these instances, the CSF findings are significantly different, usually with predominant lymphocytosis, normal CSF sugar, and negative Gram stain. The dermatologic findings of N. meningitidis are usually secondary to an underlying vasculitis; they are rarely related to concomitant coagulation defects or a combination of the two. Meningococcal infection more commonly has a rash that affects the trunk and extremities in contrast to the echovirus exanthem that usually involves the face and neck early in the infection. Purpuric lesions may also rarely be found in a fulminant pneumococcal bacteremia with meningitis as well as staphylococcal endocarditis, the latter primarily involving the finger pads.

Parameningeal Infections

Clinical Vignette

A 76-year-old man presented with sinus headaches and underwent surgical drainage of the frontal sinuses. Postoperatively, he had headaches, seizures, and mild right-sided weakness, diagnosed as a mild CVA. He was discharged home, where he had some difficulty walking and speech was “not quite normal.” He gradually worsened and 6 weeks after his surgery he could not hold anything in his right hand and became aphasic. He complained of some chills but no fever. On examination, he was awake and alert but globally aphasic, cranial nerves were intact, and gaze was conjugate. There was a right hemiparesis. WBC count was 9,700/mm3 with a normal differential. Brain CT demonstrated a hypointense left frontal lobe structural lesion with midline shift. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a multiloculated lesion with marked ring enhancement and surrounding edema extending through the frontal lobe and posteriorly toward the left parietal lobe (see Fig. 48-3). There was 1.5 mm midline shift. The lesion was aspirated using a stereotactic technique; Gram stain revealed many PMNs, many gram-positive cocci, and rare gram-negative rods. Culture grew Proteus mirabilis and Bacillus species. He was treated with 4 months of ceftriaxone and metronidazole with full resolution of speech and recovery of ambulation with the assistance of a walker.

Comment: Although parameningeal infections are relatively uncommon disorders, these lesions must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of any acute cerebral or spinal lesion (see Fig. 48-3). These processes may easily be unsuspected and thus unrecognized until it is too late to prevent permanent neurologic deficits. CT scanning is a very useful tool to exclude such predisposing lesions. Although these abscesses are easily considered within the setting of an overt infection, a precise microbial source is not always defined by the character of the clinical presentation. It is essential to always consider whether any acute spinal or cerebral lesion possibly has an infectious basis. This is particularly important in the setting of a chronic illness such as diabetes mellitus, something that often predisposes individuals to spinal epidural abscesses. The highest diagnostic and therapeutic priority is required in these settings. When identified, such processes are among the most urgent neurologic emergencies. These require immediate diagnostic and therapeutic attention. Even when appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic focus occurs, the patient’s outcome may still be guarded, as in the preceding vignette in this chapter.

Brain Abscess

Clinical Vignette

MRI is most helpful for making the initial diagnosis (Fig. 48-3). The characteristic appearance is a focal cerebral lesion with a hypodense center and a peripheral uniform ring enhancement subsequent to contrast material injection. Sometimes there is a concomitant area of surrounding edema. In these circumstances, if at all possible lumbar puncture should be avoided to prevent abscess herniation or rupture into the ventricular system.

Subdural Abscess

This is another form of life-threatening neurologic infection. It is typically characterized by a purulent collection within the potential space between the dura mater and arachnoid membrane (Fig. 48-3). An active paranasal sinusitis, particularly originating within the frontal sinuses or mastoid air cells, usually precedes extension of the infection into the subdural space. Occasionally, it is directly introduced through operative or traumatic wound sites.

CSF contains 10 to 1000 WBCs; protein level is increased, and glucose level is normal in contrast to bacterial meningitis; this is a particularly important clue if imaging studies have not been previously obtained. CT or MRI demonstrates a low-absorption extracerebral mass. A thin, moderately dense margin may be visualized with the contrast medium (Fig. 48-3).

Spinal Epidural Abscess

Clinical Vignette

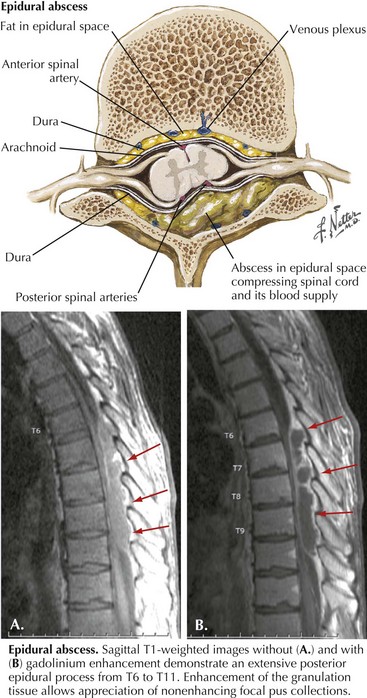

A purulent or granulomatous collection within the spinal epidural space may overlie or encircle the spinal cord, nerve roots, and nerves (Fig. 48-5). Although the infection is usually localized within three to four vertebral segments, it rarely extends the length of the spinal canal.

Specific Pathogens

Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi)

Clinical Presentation

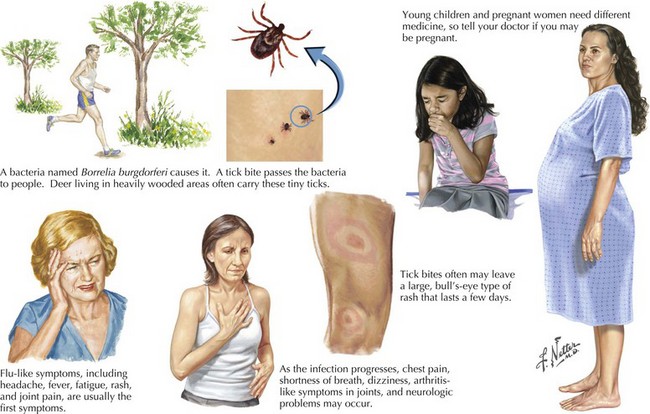

In 80% of patients in the United States, Lyme disease presents with a slowly expanding skin lesion called erythema migrans that occurs at the site of the tick bite (Fig. 48-6). Influenza-like symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, fever, headache, arthralgias, myalgias, and regional lymphadenopathy, frequently accompany the rash and are often the presenting manifestation of Lyme disease. Early localized infection is followed within days to weeks by a systemic dissemination that variously affects the nervous system, heart, or joints. Untreated, late or persistent Lyme infection ensues.

Diagnosis

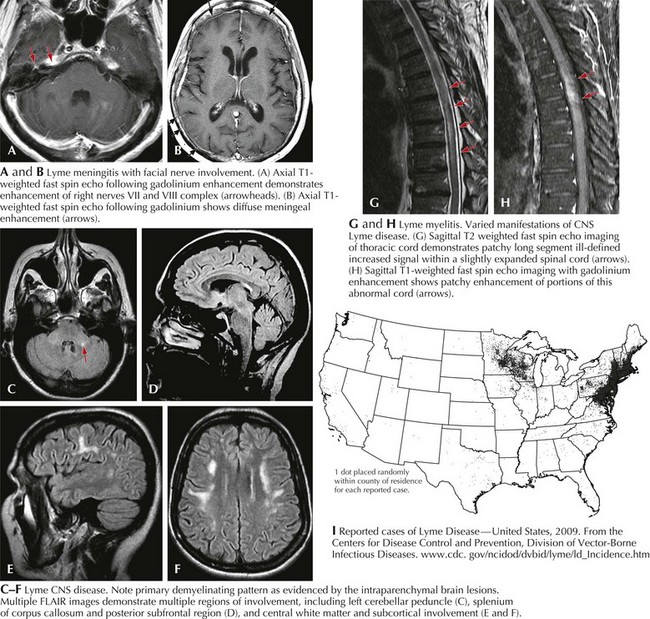

MRI may demonstrate meningitic findings (Fig. 48-7a&b), as well as cranial nerve involvement. Intraparenchymal white matter changes in the corpus callosum as well as centrum semiovale mimicking multiple sclerosis may be seen. Active enhancement is a good marker of active disease (Fig. 48-7c–f).

Tuberculosis: Brain and Spine (Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Tuberculous Meningitis

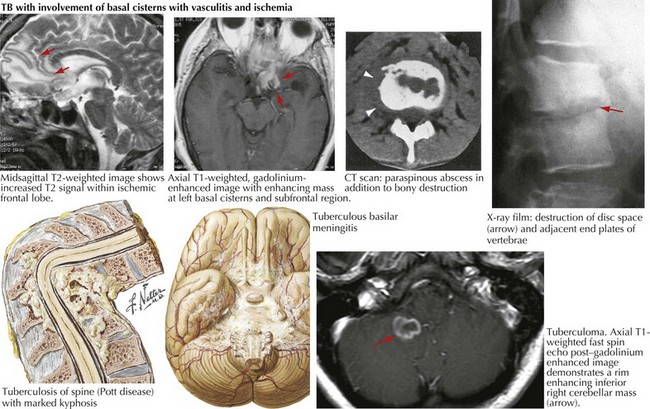

Tuberculous meningitis usually results from hematogenous meningeal seeding or contiguous spread from a tuberculoma or parameningeal granuloma, with subsequent rupture into the subarachnoid space (Fig. 48-8). Local foci of infection along the meninges, brain, or spinal cord, thought to be present from hematogenous seeding of the primary infection, also release bacilli directly into the subarachnoid space. Infection then spreads along the perivascular spaces into the brain. An intense inflammatory reaction at the brain base causes an occlusive arteritis, with small vessel thrombosis and resultant brain infarction. Direct cranial nerve compression and obstruction of CSF flow at the foramina of the fourth ventricle or at the basal cisterns may result in subarachnoid block and cerebral edema.

Cerebral Tuberculomas

Cerebral tuberculomas are less common than tuberculous meningitis. These are often calcified and are usually located in the posterior fossa, particularly the cerebellum. Although most frequently multiple, tuberculomas can be single. Contrast-enhanced MRI is generally considered the modality of choice in detecting and assessing CNS tuberculosis (Fig. 48-8). PCR and CSF culture or culture of biopsied lesional material confirms the diagnosis. Because standard medical therapy is usually successful if multidrug resistance is not identified, antituberculous therapy must be attempted before surgery is contemplated. Of course, if there are signs of impending herniation, immediate surgery is indicated.

Vertebral Tuberculosis (Pott Disease)

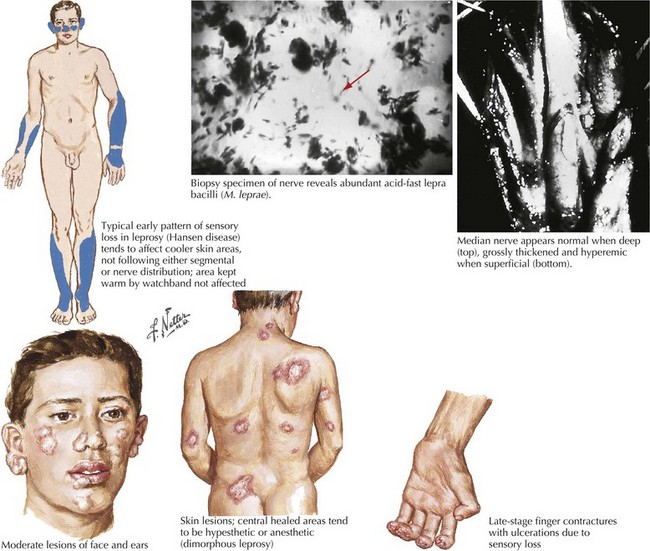

Hansen Disease (Leprosy—Mycobacterium leprae)

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The three cardinal diagnostic criteria are anesthetic skin patches, thickened nerves, and acid-fast bacilli in skin smears (Fig. 48-9). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends classification based on clinical criteria: paucibacillary if less than five skin lesions and/or one nerve is involved, or multibacillary if there are five or more skin lesions, more than two nerves involved, or both. This system determines the therapy type and duration for patients evaluated in the field where laboratory help is not available. The commonly used classification is based on the disease’s clinical spectrum, extending from tuberculoid (TT) to borderline tuberculoid (BT), borderline (BB), borderline lepromatous (BL), and lepromatous (LL). Indeterminate leprosy, seen early in the infection, is diagnosed by the presence of a single or a few skin macules having variable sensory loss.

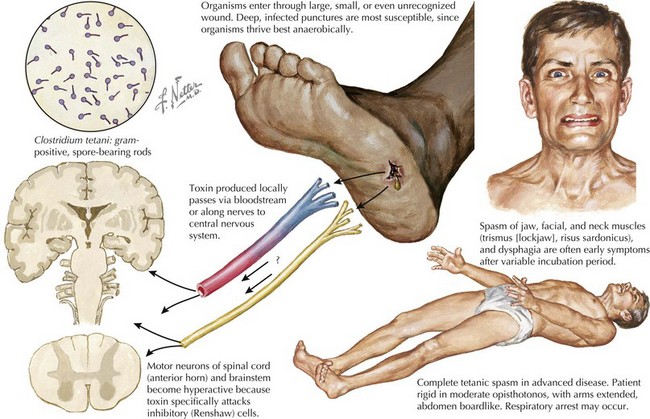

Tetanus (Clostridium tetani)

Tetanus results from the release of tetanospasmin into the bloodstream from a focus of infection by C. tetani; subsequently, it binds to the neuromuscular junction and then attaches to peripheral motor neuron nerve endings. It travels centrally up the nerve, in retrograde fashion (antidromically), to the anterior horn cells, where it enters adjacent spinal inhibitory interneurons, exerting its primary pathophysiologic effect by blocking inhibitory neurotransmitter release to the anterior horn cell. This leads to the classic muscular hypertonia and muscle spasms as agonist and antagonist muscles simultaneously contract as reciprocal inhibition is blocked (Fig. 48-10).

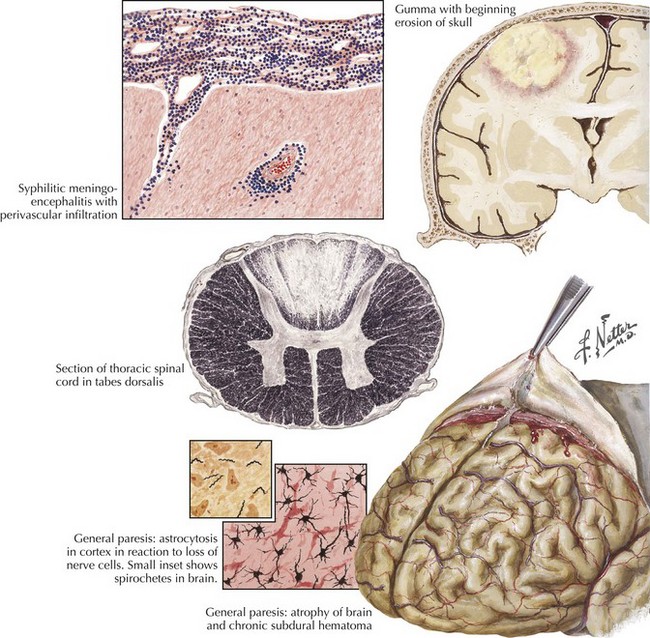

Neurosyphilis (Treponema pallidum)

Clinical Presentation

General paresis (dementia paralytica) occurs most commonly in patients older than age 40 years, from direct spirochete invasion of neural tissue causing neuronal degeneration, astrocytic proliferation, and meningitis (Fig. 48-11). Resultant degenerative and sclerotic changes produce a thickened dura mater, chronic subdural hematoma, cortical cell atrophy, and astrocyte proliferation. The frontal lobes are disproportionately affected. Progressive dementia occurs in 60% of patients, but headaches, insomnia, personality change, impaired judgment, disturbed emotional responses, slurred speech, and tremors can also develop. Argyll Robertson pupils are characteristic. RPR test results in blood and VDRL test results in CSF are positive in more than 90% of patients.

Gumma of the brain and spinal cord are rare. Symptoms are consistent with expanding CNS lesions.

Halperin JJ, Shapiro ED, Logigian E, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of nervous system Lyme disease (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2007;69:91-102.

Hildenbrand P, Craven DE, Jones R, Nemeskal P. Lyme Neuroborreliosis: manifestations of a rapidly emerging zoonosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 4-3-2009. www.ajnr.org. doi 10.3174/ajnr.A1579

Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of nervous system Lyme disease developed by the American Academy of Neurology.

Ooi WW, Moschella SL. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(6):930-937.

Ooi WW, Srinivasan J. Leprosy and the peripheral nervous system: basic and clinical aspects. Muscle Nerve Muscle Nerve. 2004 Oct;30(4):393-409.

2011 Practice Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at Accessed April 28 http://www.idsociety.org/Content.aspx?id=9088, 2011. Evidence-based statements developed to assist practitioners and patients in making decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. Guidelines for treatment of infections by organ system and organism may be found here

Sabin TD, Swift TR, Jacobson RR. Leprosy. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:1354-1379.

fingers, consistent with a right ulnar neuropathy affecting ulnar innervated structures in her right hand. Examination of the left leg revealed focal weakness of foot dorsiflexion and eversion with sensory loss on the lateral aspect of the left calf and the dorsum of the foot indicating a left common peroneal neuropathy. Both ulnar and peroneal nerves were thickened and palpable. Two subtle hypopigmented, anesthetic macules were found on her upper arm and trunk. Sensation was diminished on the ear pinna and tip of the nose.

fingers, consistent with a right ulnar neuropathy affecting ulnar innervated structures in her right hand. Examination of the left leg revealed focal weakness of foot dorsiflexion and eversion with sensory loss on the lateral aspect of the left calf and the dorsum of the foot indicating a left common peroneal neuropathy. Both ulnar and peroneal nerves were thickened and palpable. Two subtle hypopigmented, anesthetic macules were found on her upper arm and trunk. Sensation was diminished on the ear pinna and tip of the nose.