34 Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes

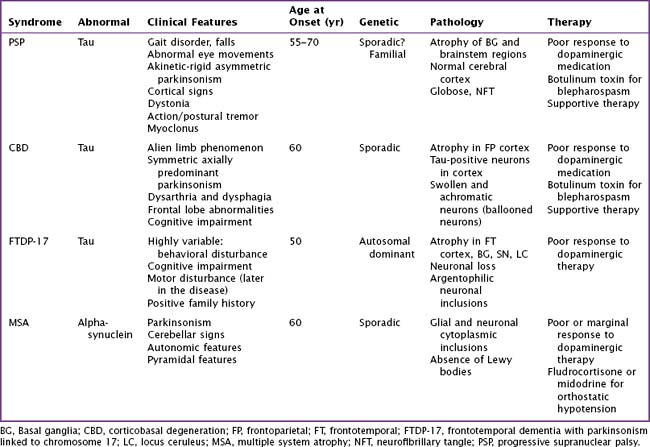

Atypical parkinsonian syndromes previously called Parkinson-plus syndromes, are chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by rapidly evolving parkinsonism in association with other signs of neurologic dysfunction beyond the spectrum of idiopathic Parkinson disease (PD). These include early postural instability, supranuclear gaze palsy, early autonomic failure, and pyramidal, cerebellar, or cortical signs. The most common disorders (Table 34-1) are progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and multiple-system atrophy (MSA). Unlike idiopathic PD, these uncommon syndromes have poor or transient responses to dopaminergic therapy and consequently a worse prognosis. These disorders are classified as tauopathies and synucleinopathies based on the accumulation of the abnormal proteins tau or alpha-synuclein within neurons and glial cells having various anatomic distribution within certain brain areas.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Clinical Vignette

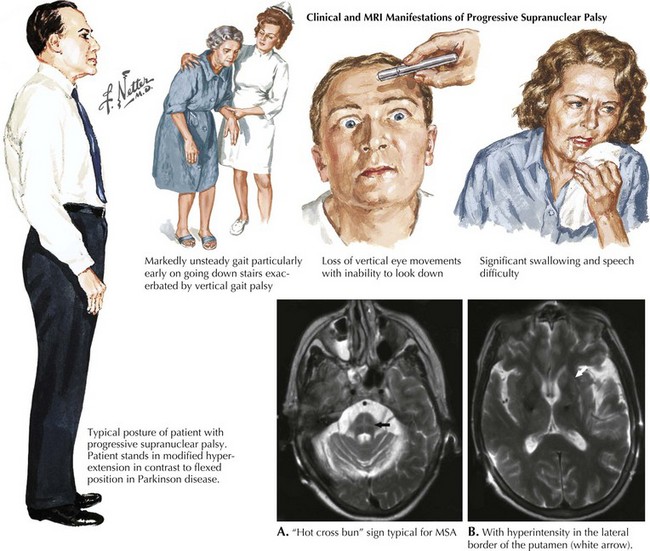

PSP is a sporadic tauopathy that has a progressive clinical course characterized by parkinsonism with supranuclear gaze palsy (Fig. 34-1), early postural instability, falls, bradykinesia, and dysarthria as well illustrated in this vignette. PSP typically does not respond to dopaminergic therapy. Its prognosis is poor, with a median survival of 5–7 years. PSP’s etiology, like that of CBD, is unknown. A genetic susceptibility may be invoked; however, to date, only the H1 MAPT haplotype has been consistently associated with a risk of developing progressive supranuclear palsy

Pathophysiology

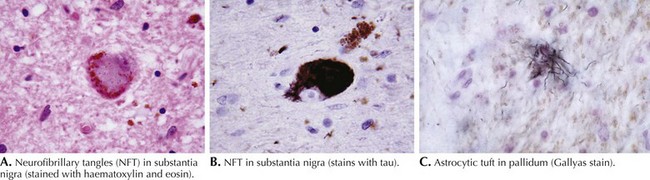

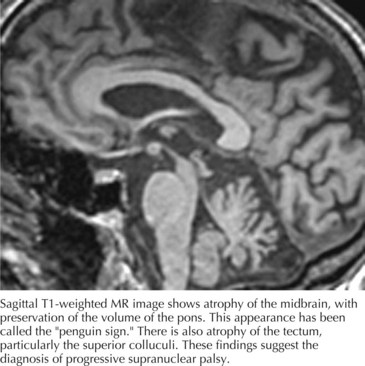

PSP is primarily a subcortical neurodegenerative tauopathy in contrast to both CBD and FTPD-17 having involvement of the cerebral cortex. Macroscopically, depigmentation is observable within the substantia nigra (SN) and locus coeruleus (LC), as well as atrophy of the pons, midbrain, and globus pallidum (Fig. 34-2). Microscopically, the most affected regions are brainstem nuclei III, IV, IX, and X, the red nucleus, LC, SN, globus pallidus, and cerebellar dentate nucleus. Tau protein accumulates within neurons as neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) and in glia as spherical neuropil threads.

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually present with gait instability and tendency to unexpectedly fall backwards; in contrast, neither of these symptoms occurs early on in Parkinson disease. The parkinsonism of PSP is typically axial and symmetric, unlike the asymmetric often single limb presentation of PD. Most patients with PSP carry an erect posture in contrast to the flexed PD stance (see Fig. 34-1). Often they lack the typical PD tremor. Dystonia is a common finding particularly early on affecting limbs, neck dystonia, or even as blepharospasm.

Diagnosis

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 34-3) often demonstrate generalized or brainstem (dorsal midbrain) atrophy. The combination of atrophy of the midbrain tegmentum with relative sparing of the basis pontis resembles “a lateral view of a standing penguin (especially, the king penguin), with a small head and big body” on a midsagittal MRI scan. Previously, appearance of the midbrain tegmentum was stated to resemble the head of a hummingbird. Whether the penguin or hummingbird sign will take flight remains to be seen, but the implication of both studies is the same: the midbrain in PSP is atrophic and MRI can be helpful to verify the clinical diagnosis.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Frontotemporal Dementia Parkinsonism–Chromosome 17

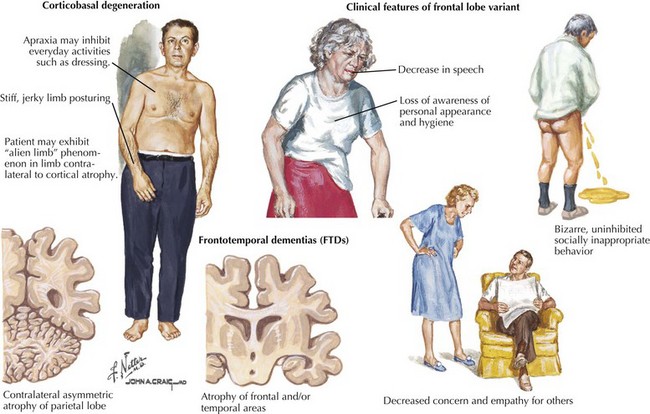

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

FTDP-17 is a highly variable neurodegenerative disease. The first symptoms typically occur in the fifth decade but range from the third to the sixth decades. The clinical onset is an insidious one. Often there is significant history of similar problems among multiple family members. Behavioral disturbances are often the initial and typical features, including disinhibition, inappropriate behavior, and poor impulse control (Fig. 34-4). Other individuals present with apathetic, socially withdrawn behavior and often neglect personal hygiene. Some individuals’ prominent psychosis, similar to schizophrenia with auditory hallucination, delusion, and paranoia, is sometimes apparent.

Multiple system atrophy

Clinical Vignette

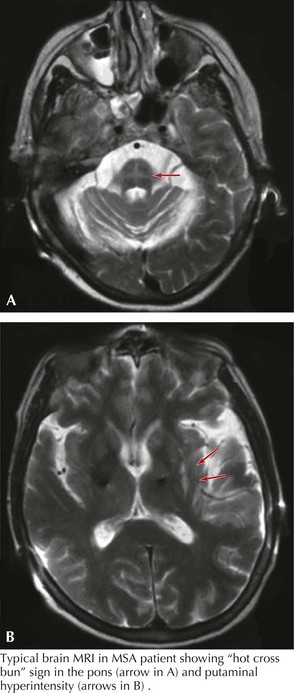

His examination was notable for hypophonic speech, stridor, square wave jerks seen during eye movement exam, orofacial dyskinesia, and antecollis. He had asymmetric akinetic rigid syndrome with more involvement of the right-sided extremities with brisker muscle stretch reflexes and the presence of a right Babinski sign. Bilateral right greater than left, finger-to-nose-to-finger and heel-to-shin ataxia was identified, right more prominent than left. He was unable to ambulate independently and required two people to support him. His gait was characterized by a wide base with significant slowness, bilateral loss of arm swing, and poor postural stability. MRI demonstrated lateral putamen and pontine cruciate patterns of T2 hyperintensity (Fig. 34-5). He had abnormal autonomic testing.

Diagnosis

Cerebellar atrophy can be demonstrated even with brain CT scans. Characteristic MRI abnormalities include hypointensity on T1 or hyperintensities on T2 in the lateral border of the putamen or putaminal atrophy. Cerebellar and pontine atrophy with the hot cross bun sign (see Fig. 34-5) in the pons are seen; however, MRI is not specific and is often normal.

Buee L, Delacourte A. Comparative biochemistry of tau in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, FTDP-17 and Pick’s Disease. Brain Pathology. 1999;9:681-693.

Dickson DW, Rademakers R, Hutton ML. Progressive supranuclear palsy: pathology and genetics. Brain Pathol. 2007 Jan;17(1):74-82.

Frank S, Clavaquera F, Tolnay M. Tauopathy models and human neuropathology: similarities and differences. Acta Neuropathol. 2008 Jan;115(1):39053. Epub 2007 Sep 5

Gibb RG, Luthert PJ, Marsden CD. Corticobasal degeneration. Brain. 1989;112:1171-1192.

Gilman S. Multiple system atrophy. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E, editors. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998:245-295.

Gilman S, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008 Aug 26;71(9):670-676.

Houghton DJ, Litvan I. Unraveling progressive supranuclear palsy: from the bedside back to the bench. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl. 3):S34106.

Litvan I, Cummings JL, Mega M. Neuropsychiatric features of corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol Nneurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:717-721.

Melquist S, Craig DW, Huentelman MJ, et al. Identification of a novel risk locus for progressive supranuclear palsy by a pooled genomewide scan of 500,288 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Apr;80(4):769-778.

Oba H, et al. New and reliable MRI diagnosis for progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2005 Jun 28;64(12):2050-2055.

Rebeiz JJ, Edwin MD, Kolodny H, et al. Corticodentatonigral degeneration with neuronal achromasia. Arch Neurol. 1986;18:20-34.

Savoiardo M, Grisoli M, Girotti F. Magnetic resonance imaging in CBD, related atypical Parkinsonian disorders, and dementias. In: Litvan I, Goetz CH, Lang A, editors. Advances in Neurology, 82. Corticobasal Degeneration and Related Disorders. Lippincott Williams &Wilkins; 2000:197-208.

Seppi K, Schocke MF, Wenning GK, et al. How to diagnose MSA early: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. J Neural Transm. 2005 Dec;112(12):1625-1634. Epub 2005 Jul 6

Wadia PM, Lang AE. The many faces of corticobasal degeneration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl. 3):S336-S340. Review

Wenning GK, Stefanova N, Jellinger KA, et al. Multiple system atrophy: a primary oligodendrogliopathy. Ann Neurol. 2008 Sep;64(3):239-243. Review