Atypical nevi

I use the term ‘atypical nevi’ to mean nevi that others might call dysplastic nevi.

Taking a detailed family history to determine if cases of melanoma have occurred in the family. Risk estimation is strongly modified by family history (see www.genomel.org)

Taking a detailed family history to determine if cases of melanoma have occurred in the family. Risk estimation is strongly modified by family history (see www.genomel.org)

Education about monitoring of nevi

Education about monitoring of nevi

Follow-up/supervision in clinic, for a period whose length is determined by risk estimation based upon family or personal history of melanoma, the competency of the patient in self examination and the clinical phenotype

Follow-up/supervision in clinic, for a period whose length is determined by risk estimation based upon family or personal history of melanoma, the competency of the patient in self examination and the clinical phenotype

Excision of atypical nevi where it is necessary to exclude melanoma

Excision of atypical nevi where it is necessary to exclude melanoma

Education about ensuring sufficient sun protection without becoming vitamin D depleted. Sunburn avoidance is crucial in that sunburn is established to be associated with melanoma risk in multiple studies. Sunbathing, independently of sunburn may also increase risk so should be avoided in those with atypical moles.

Education about ensuring sufficient sun protection without becoming vitamin D depleted. Sunburn avoidance is crucial in that sunburn is established to be associated with melanoma risk in multiple studies. Sunbathing, independently of sunburn may also increase risk so should be avoided in those with atypical moles.

Management strategy

Treatment strategies for atypical nevi:

– in the absence of worrying dermoscopic features

– reassure but give photographic information about monitoring

– if borderline consider photograph and review at 3 months

– excise if melanoma cannot be excluded after dermoscopy

– consider excision if nevus is new and/or the patient is over 50 years

– excise nevi if melanoma cannot be excluded (not usually necessary)

– assess risk based upon clinical appearance and family history

– consider genetic counseling if three or more cases of melanoma in the family, especially if those cases have multiple primaries or pancreatic cancer (www.genomel.org)

– photograph atypical nevi at high magnification and with dermoscopy

– educate the patient and partner about self-examination

– educate the family about sun protection without becoming vitamin D deficient

Specific investigations

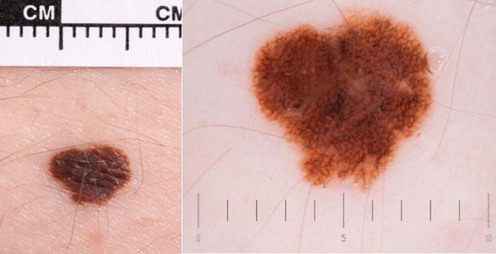

The details of how to perform dermoscopy and the criteria for atypical nevi and melanoma are beyond the scope of this book, but there are increasing numbers of dermoscopy teaching sites on the Intranet including www.genomel.org, and an Interaction Atlas of Dermoscopy CD from Medisave.

Dermoscopy: change in appearance

Dermoscopy: change in appearance Dermoscopy influencing decision to treat

Dermoscopy influencing decision to treat Dermoscopy in patients under follow-up for increased risk of melanoma

Dermoscopy in patients under follow-up for increased risk of melanoma Confocal microscopy: a pilot study

Confocal microscopy: a pilot study Mobile teledermatology

Mobile teledermatology Late diagnosis of melanomas: an assessment of the associations

Late diagnosis of melanomas: an assessment of the associations Number of melanocytic lesions excised per melanoma detected

Number of melanocytic lesions excised per melanoma detected UK melanoma treatment guidelines

UK melanoma treatment guidelines Margins of excision for atypical nevi

Margins of excision for atypical nevi