CHAPTER 26 Atypical Behavior: Self-Injury and Pica

Atypical behavior, in the form of self-injury and pica, are among the most perplexing forms of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Both are highly conspicuous behavioral phenomena that, despite many years of clinical interest and dedicated research, are not well understood. A variety of theories have been offered to explain the motivational and biological bases underlying these behaviors. However, the true reason why children and adolescents engage in such activities remains a mystery. The purpose of this chapter is to review the definition, taxonomy, and prevalence of self-injury and pica in children and adolescents. In addition, the chapter contains a review of advances made toward understanding the motivational and biological bases for engaging in these behaviors, a discussion of the indications for intervention, and a review of the latest empirically based treatment approaches.

SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR

Self-injurious behavior is defined as the deliberate infliction of harm to one’s own body.1 Self-injury in children and adolescents may take various forms, ranging from severe and suicidal behavior to relatively mild and socially acceptable tattooing, piercing, and branding. This chapter, however, focuses on the two subtypes of self-injurious behavior with which patients most commonly present for treatment: stereotyped self-injury and impulsive self-injury. Stereotyped self-injury is repetitive in nature and are observed mostly in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, mental retardation, and developmental disabilities.2 Impulsive self-injury takes the form of a habitual behavior frequently encountered in adolescents and associated with serious personality disorder.3

Common forms of stereotyped self-injury in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities include self-biting, self-punching, self-scratching, self-pinching, and repetitive banging of the head and limbs against solid, unyielding surfaces such as walls, tables, and floors. Less common forms of stereotyped self-injury include repeatedly dislocating and relocating joints (especially the fingers and jaw); repetitive eye pressing and gouging; pulling out one’s own hair, teeth, or fingernails; and twisting or tearing of the ears and genitals. Deliberate and forceful striking of the knee to the face and head is a unique and potentially lethal form of stereotyped self-injury that may result in detached retinas, serious damage to soft tissue, and fracture of the mandible and periorbital area. In rare cases, death results. Fortunately, most children with developmental disabilities who engage in stereotyped self-injury respond favorably to treatment. Behavior therapy with positive reinforcement strategies,4 medication,5 and various combinations of behavior therapy and medication6 are frequently reported as successful in virtually eliminating the disorder. However, a significant minority of children with special needs are unresponsive to treatment. Stereotyped self-injury in this refractory group is at high risk of escalating to life-threatening proportions, and as a result, affected children must use highly restrictive protective equipment, such as helmets, padded mitts, and arm and leg restraints, among other individually tailored pieces of protective clothing.7

The principal forms of impulsive self-injury, sometimes referred to as self-mutilation, include skin cutting and skin burning.8 However, episodic self-hitting, self-rubbing, self-scratching, and needle-sticking also may be observed. Skin cutting may be performed with a sharp conventional instrument, such as a razor blade, scissors, or a paring knife, or with a relatively blunt mechanism, such as a table knife. Skin cutting also may be accomplished with unconventional but nonetheless sharp objects, such as a wood splinter, a nail or screw, a bottle cap, a glass shard, and paper. Skin burning is frequently accomplished with lighted cigarettes and matches. However, the use of heated metal is not uncommon, and the use of a heated light bulb is an overlooked source. The typical profile associated with impulsive self-injury involves a mid- to late adolescent child of average or above average intelligence with comorbid borderline personality disorder and/or depression.9 Impulsive self-injurious acts are typically superficial in nature, with a low risk of lethality. Approximately two thirds of adolescents who have engaged in impulsive self-injury have reported experiencing some form of a sense of relief after an episode.10 Psychosocial approaches to the treatment of impulsive self-injury tend to focus on the underlying personality disorder or affective illness and include behavior modification, cognitive-behavioral therapy (specifically, cognitive restructuring), and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).11 Similarly, pharmacotherapy for impulsive self-injury follows loosely established guidelines for treatment of personality disorder and affective disorder; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and low-dose atypical antipsychotic medications are first- and second-line drug treatments, respectively.12

Prevalence

Stereotyped self-injurious behavior affects approximately 16% of the child and adolescent population with pervasive developmental disorder (autism, Rett syndrome, Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified), and mental retardation.13 Prevalence rates vary in accordance with the level of severity of developmental disability. Self-injury is rare (1%) in children with mild mental retardation. Prevalence rates of self-injury are 9% among children with moderate mental retardation, whereas they are 16% and 27% among children with severe and profound mental retardation, respectively. There is a slightly higher relative prevalence among boys (53%).

Impulsive self-injury affects approximately 1.5% to 3% of the adolescent population.14 Rates of 40% to 61% have been reported for samples of adolescent psychiatric inpatients.15 Prevalence rates of impulsive self-injury as high as 80% have been reported among adolescents and young adults with borderline personality disorder. Intermittent explosive disorder (75%), post-traumatic stress disorder (60%), substance abuse disorder (50%), and eating disorder (48%) are additional psychiatric conditions with elevated prevalence rates of self-injury.16 Conduct problems, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, affective disorder, eating disorder, substance abuse, family violence, family alcohol abuse, sexual abuse, and physical abuse are also frequently present in the developmental histories of adolescents with impulsive self-injury.17

Cause

The mechanisms by which self-injurious behavior is developed and maintained are not well understood. For the most part, children and adolescents who engage in either stereotyped or impulsive self-injury are a heterogeneous and ill-defined group. Despite the fact that they may be grouped into two broad categories (i.e., developmental disabilities and personality disorder) on the basis of diagnoses, the reasons why a particular child or adolescent engages in self-injury may be entirely different from those for another child or adolescent who engages in self-injury, even if the diagnoses of the two children are the same and the self-injurious behavior in question takes the same form. In this regard, researchers18–20 have delineated a number of motivational and biological hypotheses fundamental for children and adolescents who engage in self-injurious behavior. Of importance is that none of the proposed hypotheses are viewed as excluding each other. It is highly likely—and, in fact, expected—that one hypothesis overlaps with and complements one or more of the other hypotheses.

LEARNING THEORY

Self-injury in children and adolescents is a dramatic event that draws immediate attention and concern from adults. Parents, siblings, teachers, and friends, acting in good faith, may intuitively seek to provide comforting measures or modify and suspend limits or demands on a child or adolescent because it has the effect of stopping the self-injury, at least for the time being. In this regard, learning theory provides a useful insight as to how self-injury may be inadvertently reinforced and maintained by caretakers. Under certain circumstances, comforting measures intended to stop self-injury may result, paradoxically, in an increased frequency of the child’s self-injurious behavior because the child receives attention and caring after engaging in self-injury.20a Similarly, modifying or eliminating expectations in response to a child’s self-injury also runs the risk of inadvertently teaching the child that self-injury is an effective way to communicate protest and to escape from nonpreferred tasks or stressful situations. The immediate effects of providing either comforting measures or “giving in” to the child’s protests quite often results in the temporary interruption of self-injurious behavior. In the long run, however, these approaches are likely to have the unintentional effect of promoting and strengthening self-injurious behavior and worsening the child’s problem.

DEVELOPMENTAL THEORY

According to developmental theory, self-injury is a unique subset of behaviors emerging from the larger category of repetitive behaviors commonly observed in infancy.21 In this regard, repetitive behavior is seen as occurring during the normal progression of early developmental stages and reflective of the child’s maturational process. Piaget22 viewed repetitive motor movements as reflecting the earliest stages of intellectual growth (i.e., sensorimotor period of development). For the infant, engaging in repetitive acts, or “circular reactions,” as Piaget termed them, emerges from an innate propensity for repetition, which allows infants to learn about their bodies. During the first year of life, the extent to which infants continue to engage in repetitive activity affects their ability to develop adaptive environment manipulation, which ultimately, helps them understand the world. Repetitive behavior would then decrease across the normal developmental trajectory as the child learns more adaptive and mature behavior, such as communication, to interact with the environment.

For children not progressing in accordance with the normal developmental trajectory, engaging in repetitive behavior was said to have become “fixated” at levels of primary and secondary circular reactions. Repetitive motor mannerisms directed toward the self were said to represent primary circular reactions, whereas repetitive motor mannerisms directed toward the environment were said to represent secondary circular reactions. Fixation, in this regard, was representative of not only a slower development but also a deceleration and termination of progress in the latter stages of the developmental period, in which continuing cognitive growth was anticipated. In sum, fixation was thought to occur when the course of normal development was disrupted as a result of inadequate learning experience, lack of appropriate stimuli, absence of critical role models, or physical and/or cognitive impairment.

Accordingly, self-injurious behavior is viewed as resulting from the stalling of an otherwise normal and transient stage of development. Repetitive self-injurious behavior has been observed in 5% of normally developing infants and toddlers before the age of 36 months,23 usually in the form of head banging in the crib and usually with the clear communicative intent to be picked up, fed, burped, changed, or comforted because of sickness. The advent of language in the normally developing child results in no further self-injury. For children with autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation who fail to acquire language, repetitive self-injurious behavior becomes stereotypic in nature because of a “fixed primary circular reaction” based in earlier learning, in which it proved to be an efficacious means of communicating protest and discomfort and/or gaining access to care and comforting measures. It may be argued that this same line of reasoning, which overlaps extensively with the positive and negative reinforcement hypotheses of learning theory, may be applied to adolescents with impulsive self-injurious behavior and borderline personality disorder, in which a constant demand for attention is characteristic of the disorder, or those with affective disorder, in which the need to communicate distress and access safety and comforting measures may be paramount.

ORGANIC THEORY

According to organic theory, self-injurious behavior may be the product either of a genetic disorder or a nongenetic health condition. Smith-Magenis syndrome,24 Lesch-Nyhan syndrome,25 Prader-Willi syndrome,26 Cornelia de Lange syndrome,27 and Rett syndrome28 are examples of mental retardation syndromes in which chronic self-injury is characteristic of the developmental disorder. A complex motor tic, such as self-slapping or skin picking, associated with Tourette syndrome29 also is an example of a genetic disorder that may involve stereotyped self-injury. However, organic theory also allows for self-injurious behavior to occur as an artifact of a nongenetic health condition, such as epilepsy,30 otitis media,31 headache, toothache and constipation,32 menstrual pain,33 gastroesophageal reflux disease,34 and sleep difficulties.35 Children with autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation who are nonverbal and lack an effective means for communicating distress and illness may resort to self-injury in the form of repeatedly pressing or hitting an affected area possibly to achieve an anesthetic effect, or they may merely attack the affected area out of frustration over the discomfort it creates. Adolescents with personality disorder and/or affective illness also may experience an increased risk of impulsive self-injury as the result of an unrecognized health condition that produces pain, elevates discomfort, increases anxiety and agitation, or depresses mood. In this regard, they, too, may engage in self-injurious behavior in order to gain access to the “sense of relief” commonly reported to follow an episode of impulsive self-injury.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL THEORY

The dopamine hypothesis36 is pursued largely because of the known association of alterations in basal ganglia dopamine with repetitive behaviors and the behavioral comparability of seemingly driven repetitive behavior with stereotypical and impulsive forms of self-injury. According to the dopamine hypothesis, self-injurious behavior results from a deficiency of dopamine that causes receptor sites to develop “supersensitivity” to the neurotransmitter, so that low levels of dopamine across the transmission sites create exaggerated excitability and result in basal ganglia dysfunction. Support for a dopamine hypothesis is derived from positron emission tomographic studies that demonstrate dopaminergic deficits associated with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, a disorder characterized by stereotyped self-injury in the form of repetitive lip and finger biting. Additional support may be observed in studies of children with autism in which bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, produced marked improvement in a variety of repetitive behavior disorders, as well as studies of so-called atypical antipsychotics, which block D2 dopamine receptors and have been observed to be moderately effective in decreasing self-injury in children with developmental disabilities.

According to the serotoninergic hypothesis,37 self-injurious behavior is caused by alterations in serotoninergic functioning that result in pathologically altered mood and, ultimately, failure of impulse control. Approximately 50% of adolescents with personality disorder and/or affective disorder admit to thinking about engaging in self-injury less than 1 hour before acting to cut or burn themselves. The serotonin hypothesis also gains support from findings that serotonin uptake inhibitors, such as clomipramine, have been demonstrated as a moderately effective treatment of self-injurious behavior. Additional support for a serotoninergic hypothesis is derived from studies that have shown increased self-injury after depletion or administration of selected precursors that act on serotoninergic neurotransmission.

The role of endogenous opiates38 in self-injurious behavior is sought to explain both stereotyped and impulsive responding. In this regard, it has been hypothesized that for some children and adolescents, specifically, those with a demonstrated insensitivity to pain, self-injury may occur in response to a state of sensory depression brought about by chronic elevation of endogenous opiates. A second and more widely postulated theory suggests that some children with autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation may engage in stereotyped self-injurious behavior in order to gain access to endogenous opiates and, more specifically, to the favorable sensory consequence associated with its narcotic effect. This same line of reasoning may be applied to adolescents with borderline personality disorder or affective illness. Thus, gaining access to endogenous opiates through self-injury may, ironically, result in an improved sense of well-being. It is further speculated that the same children and adolescents may continue to hurt themselves, day after day, because they become addicted to the rewarding sensory consequence of the endorphins.

PSYCHODYNAMIC THEORY

Psychodynamic theory was formulated primarily as an attempt to explain impulsive self-injury in adolescent (and adult) populations with comorbid personality and affective disorders.39 It is based on the self-disclosures of individuals with a history of self-injurious behavior and, to a greater extent, on the interpretation of these self-reports by professionals charged with providing treatment. Consequently, several hypotheses generated by psychodynamic theory cannot be empirically validated. However, many of the proposed causal mechanisms very clearly and extensively overlap with much of what has been previously reviewed with regard to learning, self-regulatory, developmental, organic, and neurobiological theories. In this regard, psychodynamic theory purports that children and adolescents engage in self-injury for a variety of reasons,40 including (1) to gain access to care and comforting; (2) to distract themselves from emotional pain by causing physical pain; (3) to act as a compromise between life and death drives; (4) to punish themselves; (5) to relieve tension; (6) to feel “real” by feeling pain or seeing evidence of injury; (7) to end a dissociative episode; (8) to feel numb, “zoned out,” calm, or at peace; (9) to experience euphoric feelings; (10) to communicate their pain, anger, or other emotions to others; and (11) to nurture themselves through the process of the self-care of their wounds.

Diagnosis and Assessment Issues

Although most stereotyped and impulsive self-injurious responders are children with developmental disabilities and adolescents with serious personality disorders and/or affective illness, respectively, not every child or adolescent with these diagnoses engages in self-injurious behavior. Therefore, the assessment of self-injury must go beyond merely identifying neurodevelopmental characteristics and comorbid psychiatric features. It also must advance beyond listing the topography of the self-injury and establishing its magnitude or severity. The assessment of self-injury must be comprehensive and designed to identify the reason why the child or adolescent engages in the behavior. Seeking to establish the role of self-injury in the behavioral repertoire of a child or adolescent is an approach known as the functional assessment of behavior.41 Conducting a functional assessment of self-injurious behavior is crucial in determining which of the previously mentioned motivational and/or biological hypotheses (and combinations thereof) may be operational for any specific child.

A functional behavioral assessment of self-injury includes analyzing both the antecedent and consequent conditions that surround the self-injurious act: that is, assessing the conditions that immediately preceded the self-injurious response, as well as what resulted for the child or adolescent after he or she engaged in the self-injurious behavior. The goal of the functional assessment is to delineate causal circumstances—the events that prompted or cued the child or adolescent to engage in self-injury—as well as to identify the function or role served by the self-injurious behavior. Did the self-injury result in social attention? Did it facilitate escape from a nonpreferred or unpleasant situation? Was it a response to isolation or boredom? Did it appear to have a communicative intent, such as protest? Was the child sick (fever, headache, toothache, stomachache)? Does the child have a history of complex motor tic disorder? Does the child have a genetic disorder (mental retardation syndrome) or a chronic medical condition (epilepsy) or psychiatric condition (affective disorder)? Did the injury appear (ironically) to provide relief from discomfort? These and similar questions, including the developmental history of the behavior, must be addressed through a careful analysis of conditions surrounding the self-injurious event in order to determine the function or role played by self-injury and, consequently, how best it may be treated.

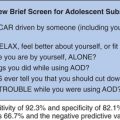

A variety of structured interviews, such as the Functional Assessment Interview,42 the Functional Assessment Checklist for Teachers and Staff,43 and the Student Guided Functional Assessment Interview,44 as well as standardized questionnaires, such as the Questions About Behavioral Function Scale,45 the Motivation Assessment Scale,46 the Stereotypy Analysis Scale,47 and the Detailed Behavior Report,48 may be used to gather information about the antecedent and consequent stimuli that may be acting to maintain stereotyped self-injurious behavior in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. Similarly, a functional approach to the assessment of self-harm in adolescents who engage in impulsive, superficial forms of self-injury may use a variety of structured interview techniques and questionnaires, including the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation Scale,49 the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire,50 and the Self-Harm Inventory.51 The Scale Points for Lethality Assessment52 also may prove useful in helping the clinician determine the potential risk of harm inherent to the patient’s impulsive self-injurious acts.

Treatment

STEREOTYPED SELF-INJURY

Behavior Modification

Studies in which learning-based behavior modification strategies are used53 account for the majority of the applied research on children with special needs who engage in stereotyped self-injurious behavior. Behavior modification aims to decrease the magnitude (frequency, duration, intensity) of a child’s self-injury by directly manipulating the causal antecedents and consequences surrounding the behavior.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS TRAINING

The development of functional communication skills is an additional form of learning-based training and an effective means of intervention, regardless of whether the self-injurious behavior is attention seeking or escape motivated. In this regard, a child who is nonverbal may be taught to attract social attention or request to leave an uncomfortable, distressing, or simply nonpreferred situation in a more adaptive manner by using an alternative form of communication, such as sign language, a picture communication board, and gestures. The use of differential reinforcement strategies, in combination with alternative forms of communication, is also a commonly employed and successful strategy for decreasing self-injurious behavior in children with developmental disabilities.

Pharmacotherapy

Approximately 65% of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities respond favorably to treatment of their self-injury with behavior modification. An additional 30% of children with developmental disabilities respond favorably to the use of behavior modification in combination with various medications.5,6 Neuroleptic drugs have a long history of being used to combat self-injury by children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation, with mixed results.54 Both low and high doses of thioridazine have been found equally effective in reducing the rate of stereotyped behavior, including self-injury. Several additional studies with D2 antagonists, such as haloperidol, have demonstrated decreased stereotyped responding, as well as decreased social withdrawal, hyperactivity, angry affect, and negative attitude. However, the presence of significant adverse effects associated with the use of neuroleptic agents, such as dystonia and tardive dyskinesia, has prompted the increased exploration of newer, alternative medications such as the so-called atypical antipsychotic drugs (e.g., risperidone, olanzapine) as treatment of self-injury.55 These medications block D2 dopamine receptors, as well as 5-HT2 receptors, and have been reported as effecting decreases in stereotyped self-injury in adolescents and young adults with mental retardation. Unfortunately, few controlled studies have been performed. Nevertheless, there is a promise of efficacy associated with these new medications that rests in the relative absence of any negative effect on cognition, as well as fewer other adverse effects typically associated with the use of older neuroleptic medications.56 SSRIs also represent a newer class of drugs that have been investigated as treatment for stereotyped self-injury, in part because of the similarity of seemingly driven stereotyped self-injury with compulsive behavior and also because of the fewer side effects associated with these medications. Fluoxetine is one such SSRI that has been studied in several open clinical trials and has been found to decrease perseverative, compulsive, and stereotyped behavior,57 as well as inappropriate speech, mood lability, and lethargy.

An opiate antagonist, naltrexone, is also used clinically. Preliminary data support the notion that self-injurious responding in some children and adolescents with developmental disabilities may be linked to defects in the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) system.38 If a child demonstrates hyposensitivity to pain, naltrexone may upregulate receptors and improve nociception. Consequently, self-injury may decrease if it is experienced by the child as an aversive event. For children who may engage in repetitive self-injury in order to gain access to the narcotic effect of endogenous opiates, naltrexone acts to block opiate receptors and, consequently, eliminates the favorable sensory consequence serving to reward and maintain the behavior.58 In the absence of a favorable sensory consequence, the self-injurious behavior should be extinguished.

Despite the potential benefits that may be derived from pharmacotherapy in any particular case involving self-injurious behavior, parents and professionals continue to express concern regarding the use of medication, particularly with children who have special needs. Direct care staff members responsible for the day-to-day management of children with developmental disabilities considered behavior modification to be a viable alternative to drug treatment for stereotyped self-injury.59 Similarly, mothers seeking behavior management training for their children with mild to moderate mental retardation preferred positive reinforcement procedures over medication.60 Although the opinions of parents and paraprofessionals are valid and certainly worthy of consideration, research has long supported the efficacy of combining medication with a variety of behavioral interventions in order to reduce or eliminate stereotyped self-injury in children with developmental disabilities.

Exercise

A review of interventions used to suppress the rate of stereotyped self-injury in children with autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation is not complete without reference to the use of physical exercise.61 Exercise may act on dopamine receptors by increasing the dopamine metabolite norepinephrine, which, in turn, may serve to counterbalance the absence of dopamine and reduce the potential for supersensitivity, resulting in a decrease of stereotyped responding. However, rates of self-injury associated with exercise may be reduced simply because of extraneous factors, such as fatigue.

IMPULSIVE SELF-INJURY

Treatment of superficial impulsive self-injury, as it applies to adolescents with average or above-average intelligence, is confounded by the fact that the behavior is not considered a discrete disorder. Instead, it is viewed as a behavior that is characteristic of another disorder, principally borderline personality disorder and affective illness. There exist a number of theories regarding the origin of borderline personality disorder10; however, none are supported empirically. The symptoms of borderline personality disorder may include labile mood, irrational thoughts, erratic behavior, unstable interpersonal relations, and poor self-image. Most adolescents with borderline personality disorder cannot stand to be alone and constantly demand attention. They also are observed as chronically angry individuals who quickly become offended by the remarks or actions of others and can become depressed quite easily. Engaging in provocative social behavior, including suicidal threats and gestures; making unreasonable demands on friends and family members; and immature tantrum-like behavior are commonly exhibited traits.

Consequently, adolescents seeking treatment for impulsive self-injury are subjected to wide variety of therapies designed to treat the larger underlying personality and/or affective disorder. In this regard, cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy account for most of the treatment literature involving impulsive self-injury.11

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Among the cognitive behavioral therapies, DBT has the most empirical support with regard to the treatment of borderline personality disorder.11 DBT is described as a problem-solving approach to treatment in which contingency management strategies, exposure tactics, cognitive restructuring, and the development of social and life skills are used to effect behavior change. The core objective of DBT with regard to impulsive self-injury is to contract with the patient to recognize and accept the feelings and circumstances that are associated with the onset of the behavior and engage in a process of behavior change. A number of well-controlled studies have demonstrated marked decreases in the impulsive self-injury of adolescent girls, as well as young adult and older women with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. In one study,62 31 female patients with borderline personality disorder demonstrated significant improvement on 10 of 11 psychopathological variables, including self-injury, after 3 months of inpatient treatment with DBT. A remarkable finding was that 42% of the treatment group receiving DBT were judged clinically recovered on a general measure of psychopathology and no longer met diagnostic criteria for personality or affective disorder. In a similar randomized study,63 27 female patients with borderline personality disorder showed dramatic decreases to zero and near-zero rates of self-injury after 1 year of outpatient DBT treatment. An important additional finding associated with the use of DBT as a treatment for self-injury in adolescents with borderline personality disorder includes the high rate of retention of patients in treatment. In virtually all controlled studies employing DBT, researchers have commented on markedly decreased rates of attrition; most reported patient retention rates two to three times greater than those reported in other treatments. Some studies have reported dropout rates as small as 10%, a remarkable statistic because the patient population receiving DBT is well known, historically, for poor compliance with treatment protocols.

Pharmacotherapy

There is limited evidence to support the use of drug interventions in the management of impulsive self-injury in adolescents with comorbid personality or affective disorders.11,12 Clinical studies typically consist of open-label medication trials and case reports. Low-dose neuroleptic drugs, such as haloperidol, have an extensive history of use in adolescents with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Unfortunately, this history includes little treatment efficacy with regard to self-injury. The newer classes of medication, such as the SSRIs, appears to hold more promise and have proved useful in the treatment of the depressive symptoms and impulsivity that commonly accompany self-injury in adolescents with borderline personality disorder.

In this regard, a study64 of 12 patients with active repetitive self-cutting were treated for 3 months with fluoxetine. Results of the study revealed that 10 of the 12 patients had stopped self-cutting by the end of the study and that the remaining 2 patients were self-cutting, on average, less than once a week. A similar result was forthcoming in a trial of sertraline in which, after 1 year of treatment, 9 of 11 patients were no longer actively engaged in self-injurious behavior.65 Unfortunately, the high dosage requirements (fluoxetine, 60 to 80 mg/day; sertraline, 325 mg/day) have raised speculation over whether patients can tolerate the levels apparently necessary to achieve the desired results.

Naltrexone, an opiate antagonist, also has demonstrated some limited utility in the treatment of adolescents with borderline personality disorder and impulsive self-injury. Altered pain perception is prevalent in numerous psychiatric disorders, including borderline personality disorder. Several studies have included reports of patients with borderline personality disorder who claim to experience no pain when actively engaging in self-injury, which is suggestive of dysfunction of normal pain mechanisms.66 Well-controlled experimental studies of such patients have confirmed their self-reports. Consequently, the use of naltrexone to antagonize the opioid peptide system has resulted in reports of increased pain perception and correspondent decreases in the magnitude of active self-injury. In this regard, a 3-week study of five female patients with borderline personality disorder and active self-injury demonstrated that all but one patient abandoned self-injury while being treated with naltrexone.67 Patients in this study also reported significant decreases in self-injurious thoughts while receiving naltrexone. Similarly, of seven female patients with borderline personality disorder, six reported reversal of analgesia and ceased engaging in self-injury during treatment with naltrexone.68 Interestingly, there are no published studies that address the popular notion that individuals with borderline personality disorder may engage in self-injury in order to gain access to the sensory consequence associated with the production of endogenous opiates, despite the vast number of self-reports indicating that among the potential consequences of their self-injury is a sense of relief and well-being.10

The use of atypical neuroleptic agents for the treatment of impulsive self-injury in borderline personality disorder was thought to hold promise equal to that of the SSRIs. However, the data in this regard are spotty, at best. There are a few scattered case reports and single subject studies that indicate the effectiveness of risperidone69 and clozapine70,71 in the remission of impulsive self-injury. The use of olanzapine, however, has not been reported as a useful treatment for impulsive self-injury associated with borderline personality disorder and appears to be far more useful in the treatment of impulsive aggressive behavior with this patient population.

Finally, it is important to note that there is no U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for either impulsive self-injury or borderline personality disorder.12 The consensus guidelines72 for pharmacotherapy propose the use of SSRIs as the first line of line treatment. This recommendation is based on the well-documented connection of serotoninergic mechanisms to the regulation of both impulsivity and affect, two commonly associated features of self-injury in borderline personality disorder. Naltrexone is generally considered a second line of treatment. However, for patients with borderline personality disorder who report that they do not experience pain as a consequence of self-injury, a trial of naltrexone may be indicated. Atypical neuroleptic agents, such as risperidone and olanzapine, do not appear to have much utility in the treatment of impulsive self-injury. However, as noted earlier, case reports have indicated that a small percentage of selected individuals may respond quite favorably to risperidone or clozapine. The same is true for the use of the α2 agonist clonidine: Several female patients with borderline personality disorder reported decreases in the subjective urge to engage in a self-injurious act.73

PICA

Pica is a medical condition defined as the persistent ingestion of nonnutritive substances for at least 1 month without an accompanying aversion to food.1 The condition is named for the magpie, one of numerous birds in the genus Pica that eats both food and nonfood items indiscriminately. Dirt, clay, pebbles, chalk, paper, string, wood, coffee grounds, cigarette butts, burnt matches, ashes, coal, coins, crayons, and plastic items (e.g., pen caps) are among the more common items ingested. However, ingesting sharp objects (such as nails, tacks, screws, nuts, bolts, glass, pins, and needles), potentially toxic substances (such as household cleaners, dishwashing fluid, laundry starch, medications (aspirin), house plants, and feces, and other poisonous substances such as gasoline, lead-based paint chips or plaster, and mercury) can lead to far more serious and potentially life-threatening consequences.74–76

Prevalence

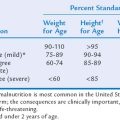

The prevalence of pica is unknown, largely because it often goes unrecognized20a but also because of changing definitions and other methodological inconsistencies across studies of the disorder. However, some reviews77 indicate that 10% to 32% of children aged 1 to 6 years exhibit this behavior. Many infants and toddlers routinely put nonfood substances in their mouths as a matter of exploration. Both intentional and accidental ingestions are common in this age group. These ingestions are not considered true pica. Typically, the early developmental habit of mouthing objects as an exploratory behavior does not persist beyond the age of 2 years. In children who engage in the behavior after age 2 years, there is a marked linear deceleration of the disorder across later childhood and adolescence; most individuals who remain afflicted have autism, mental retardation, or developmental disabilities. Children who continue to eat nonfood substances on a consistent basis after their second birthday should be evaluated for pica, as well as the presence of a developmental disability and a variety of medical conditions associated with the serious health risks that accompany chronic ingestion of nonfood substances.

Cause

CULTURAL, ETHNIC, AND FAMILIAL THEORY

Ethnic and family customs, as well as folk traditions associated with a particular culture, are viewed as possibly playing a role in the development of pica in children. Geophagia, the eating of soil, particularly clay, is a well-known folk remedy thought to suppress morning sickness.78 It is a reasonable assumption that families engaging in this activity may extend the practice to children and adolescents who complain similarly of abdominal pain, nausea, or diarrhea. The children, in turn, may learn to independently engage in the behavior whenever they feel ill; others may eat soils superstitiously with the hope of protecting themselves against sickness. The practice of pica also may have roots in religious ceremony and cult activities that center on magical beliefs.79

ORGANIC OR NUTRITIONAL THEORY

The possibility of iron deficiency anemia80 and zinc deficiency81 or substandard nutrition82 that results in vitamin and/or mineral deficiency should be considered when a child with pica is evaluated. In this regard, it is hypothesized that children and adolescents with nutritional and/or mineral deficiencies experience cravings and engage in eating nonfood substances as a compensatory mechanism to eliminate the deficiency, as well as to satisfy the craving. The empirical data, however, are mixed; some studies suggest that the incidence of dietary and mineral deficiencies is not any greater in children and adolescents with the disorder than in children and adolescents who do not eat nonfood substances.20a

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC THEORY

Pica is overrepresented among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, mental retardation, and developmental disabilities, including some children and adolescents with epilepsy.20a It is the most commonly observed eating disorder in these clinical populations. The incidence of pica in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities, comparable with the distribution of self-injurious behavior, is most frequently observed in those with severe and profound mental retardation. Like self-injurious behavior, pica in these populations is viewed as a subclass of stereotyped activity. Hypotheses identical to those proposed to explain stereotypic self-injury are invoked to explain pica behavior. In this regard, children may learn to engage in pica because it provokes adult attention (positive reinforcement) or allows escape a nonpreferred activity (negative reinforcement). Pica also may be experienced as an activity that modulates arousal (homeostatic) or, in an uncomplicated manner, a sensory activity that the child experiences as stimulating or pleasant (e.g., lead paint chips are sweet and chewy; gasoline smells good). In addition, it may be viewed from a developmental perspective as a fixed circular reaction22 or, more simply, reflective of something as straightforward as imitating the behavior of a family pet or a zoo or farm animal. Pica may also be explained by an organic hypothesis whereby the presence of a genetic disorder, such as Prader-Willi syndrome (a disorder characterized by hyperphagia), increases the risk of ingesting nonfood substances.83 Finally, neurobiological theories84 involving diminished dopaminergic neurotransmission, as well as elevated serotonin levels and the role of endogenous opiates, have been proposed to account for pica. Anxiety disorders, such as hysteria20a and obsessive-compulsive disorder,85,86 as well as other forms of psychopathology, also have been hypothesized to explain pica from a psychological perspective.

Diagnosis and Assessment Issues

Except in circumstances involving children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation, most cases of pica are easily diagnosed from self-report of the child or from interview with parents.87 However, in some instances, child or parent reluctance to report the behavior makes diagnosis difficult. Children may not disclose pica for fear of being punished or, simply, because of embarrassment. Similarly, parents may contend that they are unaware of the behavior because they are embarrassed that their child eats dirt or feces or to safeguard cultural and familial secrets and to protect themselves against potential charges of child neglect.

Treatment

The prevention of future occurrence is of the utmost importance when developing a treatment plan for a child or adolescent with pica. Parent and child education about the dangers associated with placing objects in the mouth is a crucial first step. This may be followed by instructions to parents for close supervision of the child and ways to ensure that the home environment is made as safe as possible. In the absence of effective prevention, there are many serious health risks associated with pica. Medical treatment is invariably required and often multimodal in nature. Treatment may include dietary supplements for mineral (iron or zinc) deficiencies, chelation therapy for children with clinical lead poisoning, therapy specific to the various sequelae of parasitic infection, and surgery to remove indigestible obstruction and repair den-tal injury. Psychological interventions also may be indicated, including learning-based behavior modification. In this regard, response blocking88–90 is known to be effective. However, this procedure must be implemented with virtual perfection across an extended period if favorable results are to be gained and maintained. Children and adolescents with pica related to anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive behavior, should be evaluated for possible treatment with SSRIs. Behavior modification procedures designed to positively reinforce the omission of placing nonfood substances in the mouth may be especially helpful in decreasing and eliminating the behavior in children and adolescents whose pica appears stereotypical or habitual in nature. In cases in which pica appears intractable, as may be the case in children and adolescents with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation, it may be necessary to increase the perceived magnitude of the reward associated with the absence of placing nonfood substances in the mouth by contrasting it against a mild punishment (such as loss of access to a preferred toy or removal from a preferred activity) when the behavior occurs. In cases in which pica has not responded favorably to either drug or behavioral treatments, a combination of approaches should be considered.

SUMMARY

Atypical behavior, in the form of self-injury and pica, are challenging forms of psychopathology in children and adolescents, in terms of both understanding the disorder and prescribing effective treatment. Although there are many theories as to why afflicted children and adolescents engage in self-mutilation and ingest nonfood substances, the truth remains a mystery. Despite a certain degree of homogeneity in terms of the diagnoses in the largest population of children and adolescents who are most likely to engage in these behaviors (i.e., developmental disabilities, borderline personality disorder), the children and adolescents themselves constitute a heterogeneous group. There is a great deal of variability between children within the diagnostic classification of pervasive developmental disorders, as well as across mental retardation subtypes and syndromes. The same may be said of adolescents with borderline personality disorder. It is highly unlikely that even children and adolescents sharing a identical diagnoses are engaging in the same type of self-injurious behavior or ingesting the same type of nonfood items or, if they are, that they are doing so for the same reason. Certainly, in some cases, the behavior in question is learned and can be treated with operant behavioral techniques. In cases in which the behavior appears impulsive with no apparent basis in learning, complex neurobiological hypotheses involving dopaminergic and serotoninergic mechanisms are offered as explanations. In still other cases, it may be learning in combination with a biological factor, such as neuropeptides, that is responsible for the origin and maintenance of the behavior.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

2 Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T. Self-Injurious Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2002.

3 Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al. Cognitive behavioural treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060-1064.

4 Hoch TA, Long KE, McPeak MM, et al. Self-injurious behavior in mental retardation. Matson JL, Laud RB, Matson ML, editors. Behavior Modification for Persons with Developmental Disabilities. New York: NADD Press; 2002;1:190-218.

5 Matson JL, Bamburg JW, Mayville EA, et al. Psychotropic medications and developmental disabilities: A 10-year review. Res Dev Disabil. 2000;21:263-296.

6 King BH. Pharmacological treatment of mood disturbance, aggression, and self-injury in persons with pervasive developmental disorder. J Autism Dev Disabil. 2000;30:439-445.

7 Borrero JC, Vollmer TR, Wright CS, et al. Further evaluation of the role of protective equipment in the functional analysis of self-injury. J Appl Behav Anal. 2002;35:69-72.

8 Suyemoto KL. The functions of self-mutilation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:531-554.

9 Pattison EM, Kahan J. The deliberate self-harm syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:867-872.

10 Linehan MM. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford, 1993.

11 Paris J. Recent advances in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:435-441.

12 Smith BD. Self-mutilation and pharmacotherapy. Psychiatry. 2005;October:29-37.

13 Rojahn J, Esbensen AJ. Epidemiology of self-injurious behavior in mental retardation: A review. In: Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T, editors. Self-Injurious Behavior Washington. DC: American Psychological Association; 2002:41-77.

14 Favazza AR. The coming of age of self-mutilation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:259-268.

15 Nock M, Prinstein M. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:885-890.

16 Guertin T, Lloyd-Richardson E, Spirito A. Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1062-1069.

17 Zlotnick C, Mattia JI, Zimmerman M. Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in a sample of general psychiatry patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:296-301.

18 Carr EG. The motivation of self-injurious behavior: A review of some hypotheses. Psychol Bull. 1977;84:800-816.

19 Winchel RM, Stanley M. Self-injurious behavior: A review of the behavior and biology of self-mutilation. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:306-317.

20 Favazza AR. Bodies under Siege: Self-Mutilation and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

20a. Rose EA, Porcelli JH, Neale AV. Pica: Common, but commonly missed. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13:356.

21 Sallustro F, Atwell CW. Body rocking, head banging, and head rolling in normal children. J Pediatr. 1978;93:704-708.

22 Piaget J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press, 1952.

23 Berkson G, Tupa M. Incidence of self-injurious behavior: Birth to 3 years. In: Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T, editors. Self-Injurious Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002:145-150.

24 Finncane B, Dirrigl KH, Simon EW. Characterization of self-injurious behaviour in children and adults with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 2001;106:52-58.

25 Hall S, Oliver C, Murphy G. Self-injurious behaviour in young children with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:745-749.

26 Cassidy SB. Prader-Willi syndrome. Curr Prob Pediatr. 1984;14:1-55.

27 Berney TP, Ireland M, Burn J. Behavioral phenotype of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:333-336.

28 Nomura Y, Segawa M. Characteristics of motor disturbances of the Rett’s syndrome. Brain Dev. 1990;12:27-30.

29 Cohen DJ, Bruun RD, Leckman JF. Tourette’s Syndrome and Tic Disorders: Clinical Understanding and Treatment. New York: Wiley, 1988.

30 Gedye A. Extreme self-injury attributed to frontal lobe seizures. Am J Ment Retard. 1989;94:20-26.

31 O’Reilly MF. Functional analysis of episodic self-injury correlated with recurrent otitis media. J Appl Behav Anal. 1997;30:165-167.

32 Kennedy CH, Thompson T. Health conditions contributing to problem behavior among people with mental retardation and developmental disabilities. In: Weymeyer ML, Patton JR, editors. Mental Retardation in the 21st Century. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2000:211-231.

33 Taylor DV, Rush D, Hetrick WP, et al. Self-injurious behavior within the menstrual cycle of women with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard. 1993;97:659-664.

34 Bohmer CMJ. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Intellectually Disabled Individuals. Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1996.

35 Symons FJ, Davis ML, Thompson T. Self-injurious behavior and sleep disturbance in developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2000;21:115-123.

36 Turner CA, Lewis MH. Dopaminergic mechanisms in self-injurious behavior and related disorders. In: Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T, editors. Self-Injurious Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002:165-179.

37 Simeon B, Stanley B, Francis A, et al. Self-mutilation in personality disorders: Psychological and biological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;148:1665-1671.

38 Sandman CA, Touchette P. Opioids and the maintenance of self-injurious behavior. In: Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T, editors. Self-Injurious Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002:191-204.

39 Gunderson J. Borderline Personality Disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1984.

40 Rodham K, Hawton K, Evans E. Reason for deliberate self-harm: Comparison of self-poisoners and self-cutters in a community sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:80-87.

41 Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, et al. Toward a functional assessment of self-injury. J Appl Behav Anal. 1992;27:197-209.

42 O’Neil R, Horner RH, Albin RW, et al. Functional Assessment and Program Development for Problem Behavior: A Practical Handbook, 2nd ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1999.

43 March RE, Horner RH. Feasibility and contributions of functional behavior assessment in schools. J Emotion Behav Disord. 2002;10:158-170.

44 Reed H, Thomas E, Sprague JR, et al. The Student Guided Functional Assessment Interview: An analysis of student and teacher agreement. J Behav Educ. 1997;7:33-49.

45 Matson JL, Vollmer TR. The Questions About Behavioral Function (QABF) User’s Guide. Baton Rouge, LA: Scientific Publishers, 1995.

46 Durand VM, Crimmins DB. The Motivation Assessment Scale. Topeka, KS: Monaco and Associates, 1992.

47 Pyles DA, Riordan MM, Bailey JS. The stereotypy analysis: An instrument for examining environmental variables associated with differential rates of stereotypic behavior. Res Dev Disabil. 1997;18:11-38.

48 Groden G, Lantz S. The reliability of the Detailed Behavior Report (DBR) in documenting functional assessment observations. Behav Interv. 2001;16:15-25.

49 Nock M, Prinstein M. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:885-890.

50 Gutierrez P, Osman A, Barrios F, et al. Developmental and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 2001;77:475-490.

51 Sansone R, Wiederman M, Sansone L. The Self-Harm Inventory (SHI): Development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:973-983.

52 Bongar B. Scale points for lethality assessment. In: Bongar B, editor. The Suicidal Patient: Clinical and Legal Standards of Care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1991:277-283.

53 Kahng S, Iwata BA, Lewin AB. Behavioral treatment of self-injury. Am J Ment Retard. 2002;107:212-221.

54 Reiss S, Aman MG. Psychotropic Medications and Developmental Disabilities: The International Consensus Handbook. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1998.

55 Phelps L, Brown RT, Power TJ. Pediatric Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2002.

56 Werry JS, Aman MG. Practitioner’s Guide to Psychoactive Drugs for Children and Adolescents, 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Press, 1999.

57 Ricketts RW, Goza AB, Ellis CR, et al. Fluoxetine treatment of severe self-injury in adolescents and young adults with mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:865-869.

58 Barrett RP, Feinstein C, Hole W. Effects of naloxone and naltrexone on self-injury: A double blind, placebo-controlled analysis. Am J Ment Retard. 1989;93:644-651.

59 Aman MG, Singh NN, White AJ. Caregiver perceptions of psychotropic medication in residential facilities. Res Dev Disabil. 1987;8:449-465.

60 Singh NN, Watson JE, Winton ASW. Parents’ acceptability ratings of alternative treatments for use with mentally retarded children. Behav Modif. 1987;1:17-26.

61 Baumeister AA, MacLean WE. Deceleration of SIB and stereotypic responding by exercise. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1984;5:385-394.

62 Bohus M, Haaf B, Simms T, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: A controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:487-499.

63 Verheul R, Van Den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:135-140.

64 Markovitz PJ, Calabrese JR, Schulz SC, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1064-1067.

65 Zanarini MC. Update on pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:66-70.

66 Bohus M, Limberger M, Ebner U. Pain perception during self-reported distress and calmness in patients with borderline personality disorder and self-mutilating behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2000;95:251-260.

67 Sonne S, Rubey R, Brady K. Naltrexone treatment of self-injurious thoughts and behavior. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:192-194.

68 Roth AS, Ostroff RB, Hoffman RE. Naltrexone as a treatment for repetitive self-injurious behavior: An open label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:233-237.

69 Khouzam HR, Donnelly NJ. Remission of self-mutilation in a patient with borderline personality during risperidone therapy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:348-349.

70 Chengappa KNR, Baker RW, Sirri C. The successful use of clozapine in ameliorating severe self-mutilation in a patient with borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord. 1995;9:76-82.

71 Chengappa KNR, Ebeling T, Kang JS. Clozapine reduces severe self-mutilation and aggression in psychotic patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:477-484.

72 Soloff PH. Psychopharmacology of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;23:169-192.

73 Phillipsen A, Richter H, Schmal C. Clonidine in acute aversive inner tension and self-injurious behavior in female patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1414-1419.

74 Keeling PJ, Ramsay J. Paper, pica and pseudoporphyria. Lancet. 1987;2:1095.

75 Olynyk F, Sharpe DH. Mercury poisoning in paper pica. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1056-1057.

76 Needleman H, Schell A. The long term effects of exposure to low doses of lead in childhood: An 11-year follow up report. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:83-88.

77 Motta RW, Basile DM. Pica. In: Phelps L, editor. Health Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998:524-527.

78 Dissanayake C. Of stones and health: Medical geology in Sri Lanka. Science. 2005;309:883-885.

79 Parry-Jones B, Parry-Jones WL. Pica: Symptom or eating disorder? An historical assessment. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:341-354.

80 Moore DF, Sears DA. Pica, iron deficiency, and the medical history. Am J Med. 1994;97:390-393.

81 Sayetta RB. Pica: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 1986;7:174-175.

82 Danford DE. Pica and nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1982;2:303-322.

83 Dimitropoulis A, Blackford J, Walden T, et al. Compulsive behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome: Examining severity in early childhood. Res Dev Disabil. 2006;27:190-202.

84 Ellis CR, Schnoes CJ. Eating disorder: Pica. eMed J. 2001;2:1-8.

85 Luiselli J. Pica as an obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1996;27:195-196.

86 Stein DJ, Bouwer C, van Heerden B. Pica and the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. South Afr Med J. 1996;86:1586-1592.

87 Archer L, Rosenbaum P, Streiner D. The Children’s Eating Behavior Inventory (CEBI): Reliability and validity results. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:629-642.

88 McCord BE, Grosser JW, Iwata BA, et al. An analysis of response-blocking parameters in the prevention of pica. J Appl Behav Anal. 2005;38:391-394.

89 Rapp JT, Dozier CL, Carr JE. Functional assessment and treatment of pica: A single case experiment. Behav Interv. 2001;16:111-125.

90 Hagopian LP, Adelinis JD. Response blocking with and without redirection for the treatment of pica. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34:527-530.