82

Atrophies of Connective Tissue

This chapter focuses primarily on entities in which there is a reduction in collagen and/or elastic tissue within the dermis. They vary from very common skin disorders such as striae to cutaneous manifestations of rare genetic syndromes. Loss of subcutaneous fat, i.e. lipoatrophy, is covered in Chapter 84, while acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is covered in Chapter 61 and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and cutis laxa are covered in Chapter 80.

Striae (Distensae)

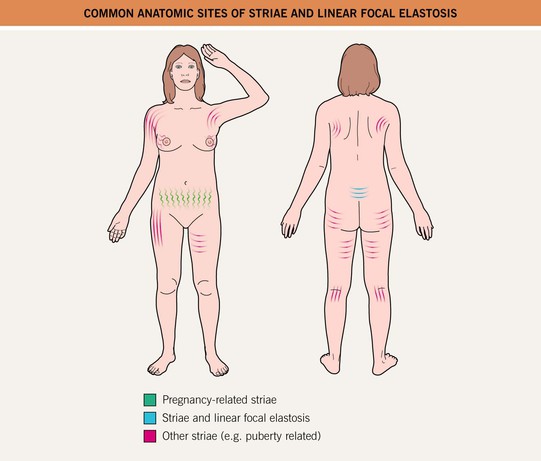

• Striae are multiple, symmetric, and arranged along the lines of cleavage, with the typical sites of involvement and characteristic patterns shown in Fig. 82.1; early lesions may be red-purple in color (striae rubra) but with time, most striae become skin-colored to white with fine wrinkling (striae alba) (Fig. 82.2).

Fig. 82.2 Striae. A Linear erythematous lesions on the abdomen (striae rubra). B Multiple linear atrophic streaks of striae alba in a teenager. C Large axillary striae in a patient receiving chronic, high-dose systemic corticosteroids. B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• DDx: linear focal elastosis, in particular when lesions are present on the lower mid-back.

Pizogenic Pedal Papules (Piezogenic Papules)

• Herniations of fat in the heel region where there is reduced dermal connective tissue; the skin-colored papules appear with the pressure of weight-bearing and disappear when the leg is raised (Fig. 82.3A); occasionally occur on the wrist.

Fig. 82.3 Pizogenic pedal papules. A Skin-colored to yellowish outpouchings on the heel represent herniation of subcutaneous fat through the plantar fascia and they are sometimes painful. B Soft nodules on the medial and plantar surface of the foot in an infant. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• In an infantile variant, larger nodules occur on the medial aspect of the heel and their appearance does not require weight-bearing (Fig. 82.3B).

Anetoderma

• Well-circumscribed, skin-colored, flaccid lesions that result from a marked focal decrease in elastic tissue within the dermis (Fig. 82.4).

Fig. 82.4 Anetoderma – primary and secondary. Lesions can range from soft, skin-colored papules that herniate upon palpation (A) to flaccid papules that have a central depression (B). The upper trunk and neck is a common location for primary anetoderma; an admixture of elevated, macular and depressed lesions is seen (C). Wrinkling of the skin from secondary anetoderma due to sarcoidosis (D) and lepromatous leprosy (E). A, Courtesy, Ronald Rapini, MD; B, Courtesy, Catherine Maari, MD, and Julie Powell, MD; C, Courtesy, Thomas Schwarz, MD. D, Courtesy, Catherine Maari, MD, and Julie Powell, MD; E, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

• Although the individual lesions of the primary form are often elevated, they can be even with the skin surface or depressed (Fig. 82.4C); however, all lesions are soft to palpation and the focal reduction in elastic tissue results in a feel similar to that of an abdominal hernia (referred to as a ‘buttonhole’ sign which is also seen in neurofibromas).

• DDx: post-traumatic scars, papular elastorrhexis (similar clinical appearance but firm to palpation), anetoderma-like scars (perifollicular elastolysis) due to acne vulgaris, pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis (flexural areas).

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini

• Minimally depressed hyperpigmented patches, primarily of the posterior trunk (Fig. 82.5); the characteristic ‘cliff-drop’ sign at the peripheral edge may be subtle; significant overlap with ‘burnt-out’ plaque-type morphea, and notably a minority of patients have both disorders.

Fig. 82.5 Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. A, B Multiple light brown patches on the back; note the subtle depression of the lesions with a ‘cliff-drop’ edge. In (B), dermal blood vessels are seen within a few patches; the white papule is a healed biopsy site. A, Courtesy, Catherine C. McCuaig, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Onset typically during adolescence or young adulthood; the patches are often oval in shape, 2–8 cm in diameter, number from one to several, and persist for decades; rarely, lesions are present at birth or arise along the lines of Blaschko (atrophoderma of Moulin; Fig. 82.6).

Fig. 82.6 Atrophoderma of Moulin. Linear hyperpigmented streaks along the lines of Blaschko. Note the subtle depression of the lesions on the upper lateral thigh. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Rx: difficult; modest improvement in hyperpigmentation reported with pigment-specific laser therapy.

Mid-Dermal Elastolysis

• Idiopathic disorder characterized by large, skin-colored patches with fine wrinkling and occasionally follicular papules with central delling; the lesions are often clinically subtle (Fig. 82.7) and histologically, there is a selective loss of elastic tissue in the mid dermis best demonstrated by special elastic stains.

Fig. 82.7 Mid-dermal elastolysis. Large patch with fine wrinkling and a slightly reticulated border on the upper back and shoulder. The junction of involved and uninvolved skin is marked with an arrow. Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD.

• Most commonly affects the trunk, neck, and arms of middle-aged Caucasian women.

Follicular Atrophoderma

• Small depressions at the sites of hair follicles.

• Clinical presentations include.

– As atrophoderma vermiculatum of the cheeks (Fig. 82.8), which can be sporadic, inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, or be a component of the keratosis pilaris atrophicans spectrum in which there is also follicular hyperkeratosis (Table 82.1; Fig. 82.9).

Fig. 82.8 Atrophoderma vermiculatum. Multiple small pitted scars on the cheek of a young girl. Note the honeycomb pattern on the lower inner cheek; the skin is said to appear ‘worm-eaten.’ The atrophic lesions may be preceded by inflammatory papules. Courtesy, Robert Hartmann, MD.

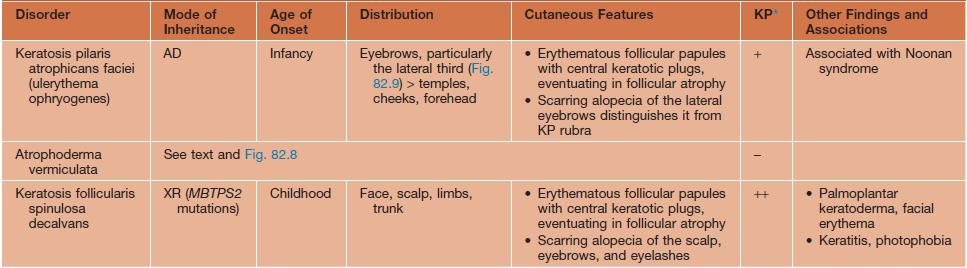

Table 82.1

The spectrum of keratosis pilaris atrophicans.

* Associated keratosis pilaris (KP) on the extremities and trunk, which does not typically eventuate in atrophy.

AD, autosomal dominant; MBTPS2, membrane-bound transcription factor peptidase, site 2 (involved in sterol regulation); XR, X-linked recessive; +, mild to moderate; ++, severe.

Fig. 82.9 Ulerythema ophryogenes. Alopecia of the eyebrows admixed with tiny follicular papules with a thin erythematous rim. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

– As follicular pits within streaks along the lines of Blaschko in the X-linked dominant disorder Conradi–Hünermann–Happle syndrome (form of chondrodysplasia punctata).

Atrophia Macularis Varicelliformis Cutis (AMVC)

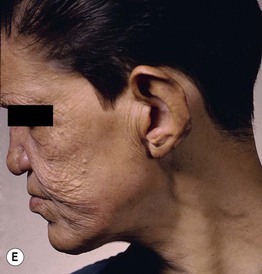

• Acquired thin linear depressions on the face that measure 2–10 mm in length and can be admixed with small circular depressions; there is no history of preceding inflammation, acne, or trauma (Fig. 82.10).

For further information see Ch. 99. From Dermatology, Third Edition.