10

Atopic Dermatitis

Introduction

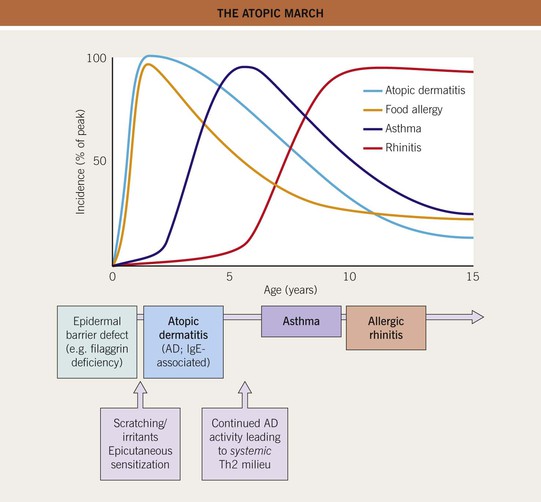

• Often accompanied by other atopic disorders such as asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (hay fever), which develop in an age-dependent sequence referred to as the atopic march (Fig. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1 The atopic march.

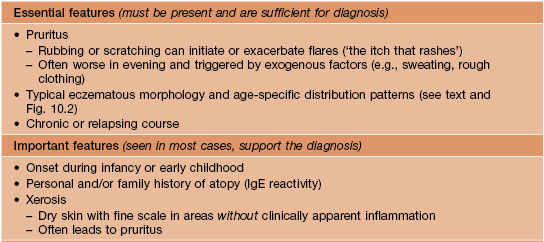

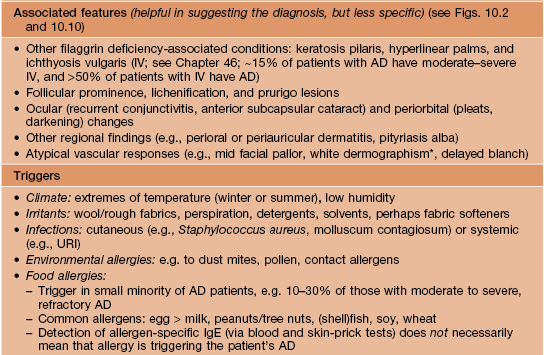

• Atopy is linked to the presence of allergen-specific serum IgE antibodies, which exist in ~70% of individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD) (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1

Diagnostic features and triggers of atopic dermatitis (AD).

* Stroking the skin leads to a white streak that reflects excessive vasoconstriction.

URI, upper respiratory infection.

Adapted from the American Academy of Dermatology Consensus Conference on Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis (Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, et al. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004;49:1088–1095).

Clinical Features and Disease Stages of AD

• Pruritic eczematous lesions are often excoriated and exist on a spectrum of acuity:

– Subacute lesions: erythematous patches or plaques with scaling and variable crusting.

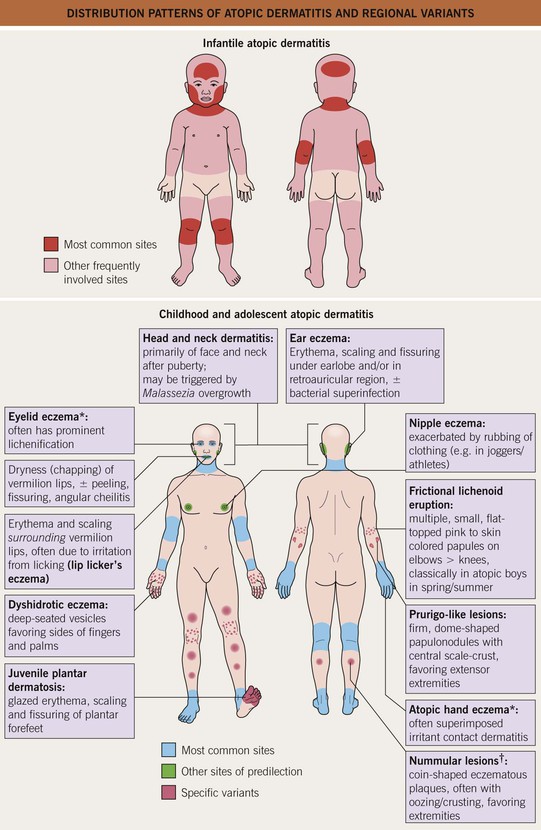

• Regional variants of AD are depicted in Fig. 10.2.

Fig. 10.2 Distribution patterns of atopic dermatitis (AD) and regional variants. *May be the only manifestation of AD in adults. †Not to be confused with nummular eczema occurring outside the setting of AD (see Chapter 11).

• Post-inflammatory hyper-, hypo-, or (in severe cases) depigmentation may be seen upon resolution of AD lesions (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3 Post-inflammatory pigmentary alteration in atopic dermatitis. A Ill-defined hypopigmented patches with variable residual erythema and scale on the shoulder and upper arm. B Post-inflammatory depigmentation in a patient with widespread, severe disease and multiple lesions of prurigo nodularis. A, Courtesy, Thomas Bieber, MD, and Caroline Bussman, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

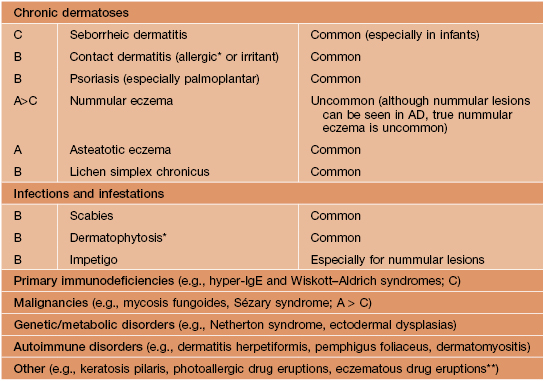

• DDx: outlined in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2

Differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).

* Common causes of autosensitization dermatitis (id reaction).

** Although drug eruptions are common, those resembling AD are uncommon.

A, adults; B, both; C, children/infants.

• AD is divided into infantile, childhood, and adolescent/adult stages with characteristic morphologies and distributions (see Fig. 10.2).

Infantile AD (Age < 2 Years)

• Usually develops after 6 weeks of age and often features acute lesions (Fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.4 Atopic dermatitis on the face of an infant. Acute lesions with oozing and serous crusting are common in this age group. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Frequently begins on the cheeks (see Fig. 10.4), forehead, and scalp; also favors the extensor aspects of the extremities and trunk (Fig. 10.5).

Childhood AD (Age 2–12 Years)

• Lesions are less acute and typically become lichenified (Fig. 10.6).

Fig. 10.6 Lichenified atopic dermatitis on the wrists and hands of children. A Pink plaques with excoriation and hemorrhagic crusting as well as lichenification. B Thick lichenified plaques. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Favors the antecubital and popliteal fossae (flexural eczema) (Fig. 10.7), wrists (see Fig. 10.6)/ankles, hands/feet, neck, and periorificial regions of the face.

Fig. 10.7 Childhood atopic dermatitis. A Flexural eczema in the popliteal fossa. Note the excoriations and hemorrhagic crusting. B Atopic cheilitis involving both the vermilion lip and surrounding skin (lip licker’s eczema). Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Often associated with widespread xerosis.

• ≥50% of children with AD go into remission by 12 years of age.

Adolescent/Adult AD (Age > 12 Years)

• Subacute to chronic, lichenified lesions with distribution similar to childhood AD.

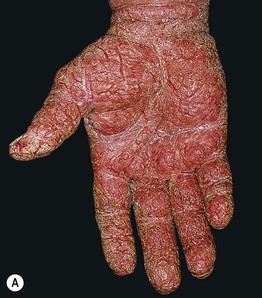

• Some patients have chronic involvement limited to a particular site, e.g. the hands or face (especially the eyelids) (Fig. 10.8; see Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.8 Atopic dermatitis in adolescents and adults. A Severe chronic hand eczema with an irritant as well as atopic component in an adult. B Extensive facial involvement in an adult.

• Chronic papular lesions may develop due to habitual scratching or rubbing (Fig. 10.9).

Fig. 10.9 Chronic papular lesions in an adult with atopic dermatitis. This resulted from habitual scratching and rubbing in the setting of long-standing disease. Courtesy, Thomas Bieber, MD, and Caroline Bussman, MD.

• More often extensive or even erythrodermic if continuous since childhood.

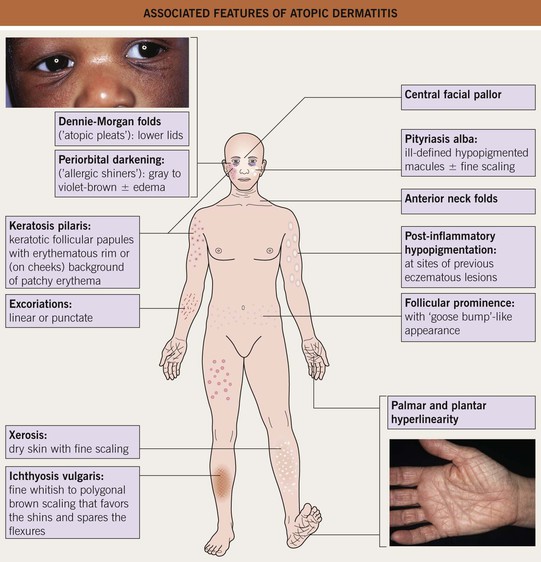

Associated Features of AD

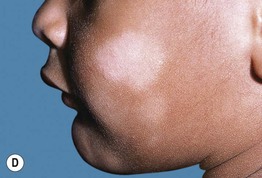

• Figs. 10.10 and 10.11 present findings that are frequently associated with AD.

Fig. 10.11 Associated findings in patients with atopic dermatitis. A Keratosis pilaris. Note the discrete perifollicular papules with central keratotic cores on the extensor surface of the upper arm. Each papule has a rim of erythema. B, C Keratosis pilaris rubra on the lateral face. This variant is characterized by tiny, grain-like follicular papules superimposed on confluent erythema. D Pityriasis alba. Note the slight scale associated with the hypopigmented macules and patches on the cheeks. B, C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; D, Courtesy, Anthony J. Mancini, MD.

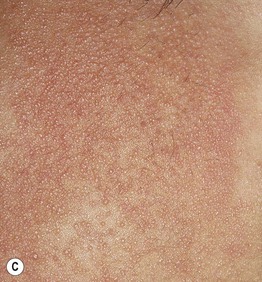

Keratosis Pilaris

• Affects >40% of patients with AD and ~15% of the general population.

• Onset typically in childhood; may improve after puberty (especially facial involvement).

• Keratotic follicular papules, often with a rim of erythema (see Fig. 10.11A) or (especially on the cheeks) a background of patchy erythema.

• Keratosis pilaris rubra (KPR) has prominent, confluent background erythema (see Fig. 10.11B,C).

• Keratosis pilaris atrophicans is a rare atrophic variant that favors the lateral eyebrows.

Pityriasis Alba

• Common in children/adolescents, especially those with AD and tan or darkly pigmented skin.

• Ill-defined hypopigmented macules and patches (usually 0.5–3 cm) with subtle fine scaling.

• Located on face (especially cheeks) (see Fig. 10.11D) > shoulders and arms.

• Rx: regular use of sunscreens may make pityriasis alba less noticeable.

Complications of AD

• An impaired skin barrier and modified immune milieu predispose AD patients to cutaneous infections.

• Affected skin is usually colonized by Staphylococcus aureus, and impetiginization (which can also result from Streptococcus pyogenes) (Fig. 10.12), folliculitis, and furunculosis frequently occur.

Fig. 10.12 Infected hand dermatitis in a patient with atopic dermatitis. There is impetigo-like crusting as well as pustules. Courtesy, Louis Fragola, MD.

• Eczema herpeticum typically presents with rapid development of numerous monomorphic, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusting (Fig. 10.13); vesicles may or may not be evident.

Fig. 10.13 Eczema herpeticum. Note the monomorphic erosions and hemorrhagic crusts. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Molluscum contagiosum infections result in an increased number of lesions, usually with associated dermatitis (see Chapter 68).

• Potential ocular complications of AD are listed in Table 10.1.

Triggers of AD

Treatment of AD

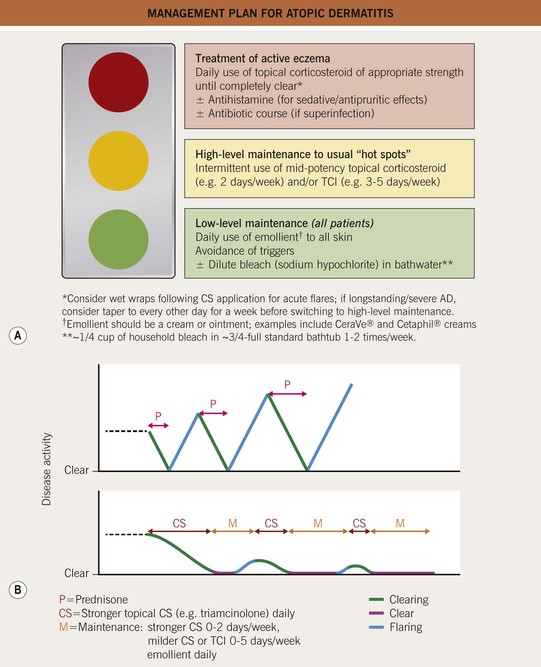

• There are two major components to management of AD (Fig. 10.14).

– Treatment of active dermatitis with anti-inflammatory agent(s).

Fig. 10.14 Management plan for atopic dermatitis. A The therapeutic regimen should include both treatment of active eczema and maintenance (low-level in all and high-level in some patients). B Intermittent courses of a systemic CS result in rebound flares and worsening of disease over time. In contrast, a proactive regimen utilizing topical CS leads to longer clear periods and milder disease over time. TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor.

– Daily luke-warm bath (preferred for infants/children) or shower with limited use of a mild cleanser.

• Topical anti-inflammatory agents.

– First-line: topical CS of appropriate strength – higher potency for thick/lichenified plaques and lesions on hands/feet, lower potency for thinner lesions and body folds – used once or twice daily until eczema is completely clear.

– High-level maintenance with intermittent use of a topical CS and/or TCI (see Fig. 10.14) to usual sites of eczema once clear can help to control subclinical inflammation and prevent flares.

• Phototherapy and systemic anti-inflammatory agents.

– Narrowband UVB (often induces remission) > UVA1 (for acute flares) > UVA-broadband UVB combination.

– Systemic anti-inflammatory therapy should be restricted for severe, recalcitrant AD.

– Systemic CS therapy should be avoided due to the high likelihood of significant rebound flares (see Fig. 10.14) and the unacceptable side effects of long-term use; uncommon exception: severe acute flare (e.g., with a specific trigger) resistant to aggressive topical management – this short course of systemic CS must be transitioned to a topical regimen, phototherapy, or another systemic agent.

• Adjunctive pharmacologic therapy.

– Controlled trials of nonsedating antihistamines, leukotriene antagonists, antibiotics (oral or topical) aimed at reducing colonization, and probiotics have not consistently demonstrated efficacy as treatments of AD; dilute sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths may be of benefit (see Fig. 10.14).

For further information see Ch. 12. From Dermatology, Third Edition.